Studies in Crime Writing – Issue 2 – 2019 © Reshmi Dutta-Flanders The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Easychair Preprint Hercule Poirot, Mon (Faux)

EasyChair Preprint № 6064 Hercule Poirot, Mon (Faux) Ami: a Corpus Study on Agatha Christie’s Use of Language to Develop Character Ellen Carter EasyChair preprints are intended for rapid dissemination of research results and are integrated with the rest of EasyChair. July 13, 2021 Hercule Poirot, Mon (Faux) Ami 1 Hercule Poirot, Mon (Faux) Ami: A Corpus Study on Agatha Christie’s Use of Language to Develop Character Ellen Carter1 11LiLPa – Linguistique, Langues, Parole – UR 1339, Université de Strasbourg, France Author Note The author declares that there no conflicts of interest with respect to this preprint. Correspondence should be addressed to Ellen Carter, Université de Strasbourg, 22 Rue René Descartes, 67084 Strasbourg CEDEX, France. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9249-5298 Email: [email protected] Hercule Poirot, Mon (Faux) Ami 2 Abstract This corpus analysis investigates Agatha Christie’s use of discourse in the person of her fictional Belgian detective, Hercule Poirot. By focusing on a specific linguistic trait – false friends – it presents evidence of how Christie used this trait to develop Poirot’s character across his thirty- three novels. Moreover, it shows that this trait is almost completely absent from the four novels featuring Poirot written by Sophie Hannah, who was chosen by Christie’s estate to continue his adventures. Keywords: discourse analysis, corpus stylistics, false friends, Agatha Christie Hercule Poirot, Mon (Faux) Ami 3 Hercule Poirot, Mon (Faux) Ami: A Corpus Study on Agatha Christie’s Use of Language to Develop Character Corpora have been used to analyze various text types and targets, including discourse analysis (Baker & McEnery, 2015), corpus stylistics of speech presentation (Semino & Short, 2004), corpus stylistics of popular fiction (Mahlberg & McIntyre, 2011) and the process of characterization in fiction (Mahlberg, 2012). -

Bibliography

Bibliography Works by Agatha Christie The following works are referred to in the text. They are listed under the standard British titles, with American titles in brackets. Date of the first publication is given. Works are referred to in the text by an abbreviated form of the British title, given in square brackets in this list. Since there have been so many editions of the novels, references are to the chapter numbers and not to the page. The current standard edition is published by Harper-Collins in the United Kingdom and by Dodd Mead in the United States. 4.50 from Paddington (What Mrs McGillicuddy Saw), 1957 [4.50] The ABC Murders, 1936 [ABC] The Adventure of the Christmas Pudding, 1960 [Pudding] After the Funeral (Funerals Are Fatal), 1953 [Funeral] And Then There Were None, 1939 [None] Appointment with Death, 1938 [Appointment] At Bertram’s Hotel, 1965 [Bertram] Autobiography, 1977 The Body in the Library, 1942 [Library] By the Pricking of My Thumbs, 1968 [Pricking] Cards on the Table, 1936 [Cards] A Caribbean Mystery, 1964 [Caribbean] Cat among the Pigeons, 1959 [Cat] The Clocks, 1963 [Clocks] Crooked House, 1949 [Crooked] Curtain, 1975 [Curtain] Dead Man’s Folly, 1956 [Folly] Death Comes As the End, 1945 [Comes End] Death in the Clouds (Death in the Air), 1935 [Clouds] Death on the Nile, 1937 [Nile] Destination Unknown (So Many Steps to Death), 1954 [Destination] Dumb Witness (Poirot Loses a Client), 1937 [Witness] Elephants Can Remember, 1972 [Elephants] Endless Night, 1967 [Endless] Evil under the Sun, 1941 [Sun] Five Little Pigs -

Agatha Christie Third Girl

Agatha Christie Third Girl A Hercule Poirot Mystery To Norah Blackmore Contents Cover Title Page Dedication Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter Six Chapter Seven Chapter Eight Chapter Nine Chapter Ten Chapter Eleven Chapter Twelve Chapter Thirteen Chapter Fourteen Chapter Fifteen Chapter Sixteen Chapter Seventeen Chapter Eighteen Chapter Nineteen Chapter Twenty Chapter Twenty-One Chapter Twenty-Two Chapter Twenty-Three Chapter Twenty-Four Chapter Twenty-Five About the Author Other Books by Agatha Christie Credits Copyright About the Publisher One Hercule Poirot was sitting at the breakfast table. At his right hand was a steaming cup of chocolate. He had always had a sweet tooth. To accompany the chocolate was a brioche. It went agreeably with chocolate. He nodded his approval. This was from the fourth shop he had tried. It was a Danish pâtisserie but infinitely superior to the so-called French one nearby. That had been nothing less than a fraud. He was satisfied gastronomically. His stomach was at peace. His mind also was at peace, perhaps somewhat too much so. He had finished his Magnum Opus, an analysis of great writers of detective fiction. He had dared to speak scathingly of Edgar Allen Poe, he had complained of the lack of method or order in the romantic outpourings of Wilkie Collins, had lauded to the skies two American authors who were practically unknown, and had in various other ways given honour where honour was due and sternly withheld it where he considered it was not. He had seen the volume through the press, had looked upon the results and, apart from a really incredible number of printer’s errors, pronounced that it was good. -

Agatha Christie

book & film club: Agatha Christie Discussion Questions & Activities Discussion Questions 1 For her first novel,The Mysterious Affair at Styles, Agatha Christie wanted her detective to be “someone who hadn’t been used before.” Thus, the fastidious retired policeman Hercule Poirot was born—a fish-out-of-water, inspired by Belgian refugees she encountered during World War I in the seaside town of Torquay, where she grew up. When a later Poirot mystery, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, was adapted into a stage play, Christie was unhappy that the role of Dr. Sheppard’s spinster sister had been rewritten for a much younger actress. So she created elderly amateur detective Jane Marple to show English village life through the eyes of an “old maid”—an often overlooked and patronized character. How are Miss Marple and Monsieur Poirot different from “classic” crime solvers such as police officials or hard-boiled private eyes? How do their personalities help them to be more effective than the local authorities? Which modern fictional sleuths, in literature, film, and television, seem to be inspired by Christie’s creations? 2 Miss Marple and Poirot crossed paths only once—in a not-so-classic 1965 British film adaptation of The ABC Murders called The Alphabet Murders (played, respectively, by Margaret Rutherford and Tony Randall). In her autobiography, Christie writes that her readers often suggested that she should have her two iconic sleuths meet. “But why should they?” she countered. “I am sure they would not enjoy it at all.” Imagine a new scenario in which the shrewd amateur and the egotistical professional might join forces. -

Hercule Poirot Mysteries in Chronological Order

Hercule Poirot/Miss Jane Marple Christie, Agatha Dame Agatha Christie (1890-1976), the “queen” of British mystery writers, published more than ninety stories between 1920 and 1976. Her best-loved stories revolve around two brilliant and quite dissimilar detectives, the Belgian émigré Hercule Poirot and the English spinster Miss Jane Marple. Other stories feature the “flapper” couple Tommy and Tuppence Beresford, the mysterious Harley Quin, the private detective Parker Pyne, or Police Superintendent Battle as investigators. Dame Agatha’s works have been adapted numerous times for the stage, movies, radio, and television. Most of the Christie mysteries are available from the New Bern-Craven County Public library in book form or audio tape. Hercule Poirot The Mysterious Affair at Styles [1920] Murder on the Links [1923] Poirot Investigates [1924] Short story collection containing: The Adventure of "The Western Star", TheTragedy at Marsdon Manor, The Adventure of the Cheap Flat , The Mystery of Hunter's Lodge, The Million Dollar Bond Robbery, The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb, The Jewel Robbery at the Grand Metropolitan, The Kidnapped Prime Minister, The Disappearance of Mr. Davenheim, The Adventure of the Italian Nobleman, The Case of the Missing Will, The Veiled Lady, The Lost Mine, and The Chocolate Box. The Murder of Roger Ackroyd [1926] The Under Dog and Other Stories [1926] Short story collection containing: The Underdog, The Plymouth Express, The Affair at the Victory Ball, The Market Basing Mystery, The Lemesurier Inheritance, The Cornish Mystery, The King of Clubs, The Submarine Plans, and The Adventure of the Clapham Cook. The Big Four [1927] The Mystery of the Blue Train [1928] Peril at End House [1928] Lord Edgware Dies [1933] Murder on the Orient Express [1934] Three Act Tragedy [1935] Death in the Clouds [1935] The A.B.C. -

If You Want to Read the Books in Publication

If you want to read the books in publication order before you discuss them this is the list for you. For the books the year indicates the first publication, whether in the US or UK, and where possible we have given the alternative US/UK titles. The collections listed are those that feature the first book appearance of one or more stories: 1920 The Mysterious Affair at Styles 1922 The Secret Adversary 1923 Murder on the Links 1924 The Man in the Brown Suit 1924 Poirot Investigates – containing: The Adventure of the ‘Western Star’ The Tragedy at Marsdon Manor The Adventure of the Cheap Flat The Mystery of Hunter’s Lodge The Million Dollar Bond Robbery The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb The Jewel Robbery at the Grand Metropolitan The Kidnapped Prime Minister The Disappearance of Mr Davenheim The Adventure of the Italian Nobleman The Case of the Missing Will 1925 The Secret of Chimneys 1926 The Murder of Roger Ackroyd 1927 The Big Four 1928 The Mystery of the Blue Train 1929 The Seven Dials Mystery 1929 Partners in Crime – containing: A Fairy in the Flat A Pot of Tea The Affair of the Pink Pearl The Adventure of the Sinister Stranger Finessing the King/The Gentleman Dressed in Newspaper The Case of the Missing Lady Blindman’s Buff The Man in the Mist The Crackler The Sunningdale Mystery The House of Lurking Death The Unbreakable Alibi The Clergyman’s Daughter/The Red House The Ambassador’s Boots The Man Who Was No.16 1930 The Mysterious Mr Quin – containing: The Coming of Mr Quin www.AgathaChristie.com The Shadow on the Glass At the ‘Bells -

Poirot Reading List

Suggested Reading order for Christie’s Poirot novels and short story collections The most important point to note is – make sure you read Curtain last. Other points to note are: 1. Lord Edgware Dies should be read before After the Funeral 2. Five Little Pigs should be read before Elephants Can Remember 3. Cat Among the Pigeons should be read before Hallowe’en Party 4. Mrs McGinty’s Dead should be read before Hallowe’en Party and Elephants Can Remember 5. Murder on the Orient Express should be read before Murder in Mesopotamia 6. Three Act Tragedy should be read before Hercule Poirot’s Christmas Otherwise, it’s possible to read the Poirot books in any order – but we suggest the following: The Mysterious Affair at Styles 1920 Murder on the Links 1923 Christmas Adventure (short story) 1923 Poirot Investigates (short stories) 1924 Poirot's Early Cases (short stories) 1974 The Murder of Roger Ackroyd 1926 The Big Four 1927 The Mystery of the Blue Train 1928 Black Coffee (play novelisation by Charles Osborne) 1997 Peril at End House 1932 The Mystery of the Baghdad Chest (short story) 1932 Second Gong (short story) 1932 Lord Edgware Dies 1933 Murder on the Orient Express 1934 Three Act Tragedy 1935 Death in the Clouds 1935 The ABC Murders 1936 Murder in Mesopotamia 1936 Cards on the Table 1936 Yellow Iris (short story) 1937 Murder in the Mews (four novellas) 1937 Dumb Witness 1937 Death on the Nile 1937 Appointment with Death 1938 Hercule Poirot's Christmas 1938 Sad Cypress 1940 One, Two Buckle my Shoe 1940 Evil Under -

THE HOLLOW Agatha Christie

THE HOLLOW Agatha Christie Chapter 1 At 6:13 a.m. on a Friday morning Lucy Angkatell's big blue eyes opened upon another day, and as always, she was at once wide awake and began immediately to deal with the problems conjured up by her incredibly active mind. Feeling urgently the need of consultation and conversation, and selecting for the purpose her young cousin Midge Hardcastle, who had arrived at The Hollow the night before, Lady Angkatell slipped quickly out of bed, threw a negligee round her still graceful shoulders, and went along the passage to Midge's room. Since she was a woman of disconcertingly rapid thought processes, Lady Angkatell, as was her invariable custom, commenced the conversation in her own mind, supplying Midge's answers out of her own fertile imagination. The conversation was in full swing when Lady Angkatell flung open Midge's door. "- And so, darling, you really must agree that the weekend is going to present difficulties!" "Eh? Hwah?" Midge grunted inarticulately, aroused thus abruptly from a satisfying and deep sleep. Lady Angkatell crossed to the window, opening the shutters and jerking up the blind with a brisk movement, letting in the pale light of a September dawn. "Birds!" she observed, peering with kindly pleasure through the pane. "So sweet." "What?" "Well at any rate, the weather isn't going to present difficulties. It looks as though it had set in fine. That's something. Because if a lot of discordant personalities are boxed up indoors, I'm sure you will agree with me that it makes it ten times worse. -

Agatha Christie's Doctors (BMJ 2010;341:C6438)—Web Appendix

Agatha Christie’s doctors (BMJ 2010;341:c6438)—web appendix Herbert G Kinnell Incompetent doctors Newly qualified Dr Sarah King thinks the murder victim in Appointment with Death died of natural causes. A couple of “tame psychiatrists” are mentioned in Crooked House. The rich wife‟s doctor is an incompetent in A Caribbean Mystery. In The Adventure of the Christmas Pudding we hear hospital treatment being compared unfavourably with previous times: “Ah, doctors nowadays, they have you out of hospital before you can hardly stand on your feet.” Aunt Ada in By the Pricking of My Thumbs says: “That‟s how doctors make their living. Giving them boxes and boxes and bottles and bottles of tablets. Yellow tablets, pink tablets, green tablets, even black tablets … Brimstone and treacle they used to use in my grandmother‟s day. I bet they were as good as anything …” The murderous Dr Roberts in Cards on the Table falsely claims: “When we poison our patients it‟s entirely by accident.” The GP in The Tragedy at Marsdon Manor concludes that his 45 years of medical experience is sometimes “not worth a jot.” The arrogant, insolent, “obstinate as a pig” Dr Adams in The Cornish Mystery insists vehemently that the poisoned dentist died from gastritis. Poirot responds that if a doctor “lacks doubt he is not a doctor, he is an executioner.” Dr Stillingfleet believes the millionaire‟s murder is suicide in The Dream. In Endless Night Dr Shaw, a main character in the novel, goes largely unnoticed, even though one character comments: “Some doctor or other is always giving them powders and pills, stimulants or pep pills, or tranquillisers, things that on the whole they‟d be better without.” Dr Burton in The House of Lurking Death opines that three recent poisonings of people in big houses were down to socialist agitation. -

Hercule Poirot – the Fictional Canon

Hercule Poirot – The fictional canon Rules involving "official" details of the "lives" and "works" of fictional characters vary from one fictional universe to the next according to the canon established by critics and/or enthusiasts. Some fans of Agatha Christie's Hercule Poirot have proposed that the novels are set on the date they were published, unless the novel itself gives a different date. It has further been proposed that only works written by her (including short stories, the novels and her play Black Coffee) are to be considered canon by most fans and biographers. This would render everything else (plays, movies, television adaptations, etc.) as an adaptation, or secondary material. A contradiction between the novels can be resolved, in most cases, by going with the novel that was published first. An example of this would be the ongoing controversy over Poirot's age. Taken at face value it appears that Poirot was over 125 years old when he died. Though the majority of the Hercule Poirot novels are set between World War I and World War II, the later novels then set him in the 1960s (which is contemporary with the time Agatha Christie was writing even though it created minor discrepancies). Many people believe, from her later works, that Poirot retired from police work at around 50, but this is untrue, because as shown in the short story "The Chocolate Box", he retired at around 30. By accepting the date given in "The Chocolate Box" over later novels, which never gave precise ages anyway, it can be explained why Poirot is around for so long. -

Social Issues in Agatha Christie's Mysteries: Country, Class, Crime, Clothes and Children

SBORNlK PRACl F1LOZOF1CKE FAKULTY BRNENSKE UNIVERZITY STUDIA MINORA FACULTATIS PHILOSOPHICAE UNIVERSITATIS BRUNENSIS S 3, 1997— BRNO STUDIES IN ENGLISH 23 LIDIA KYZL1NKOVA SOCIAL ISSUES IN AGATHA CHRISTIE'S MYSTERIES: COUNTRY, CLASS, CRIME, CLOTHES AND CHILDREN The works of Agatha Christie are now generally agreed to rise well above the level of entertainment and a good many scholars are prepared to take her art, the skill of devising fresh and insoluble puzzles, with the seriousness proper to a Joyce or James or Lawrence. T. S. Eliot once planned a great tome on the de tective novel, with a whole swath devoted to her books. Apart from her pio neering work in the full-length novel of the detective genre, her puzzling plots, a whole range of exquisite characters, her famous and less famous sleuths, ex cellent comic relief with Watson-like and some cardboard figures, her pleasant and well-handled romance, or her own character and the instinct which made her work such a success, there is yet another area of interest: mystery writers tend to accumulate a surprising amount of accurate or at least very plausible information about everyday life, and because Agatha Christie's career spans so many decades, decades which have seen so many dramatic changes in British life, her books are thus a rich lode for social historians. Agatha Christie's first detective novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, was published in the very first year of a new decade, the 1920s, and immediately here we have our first tastes of many things that are to come in what will prove to be a long and satisfying career. -

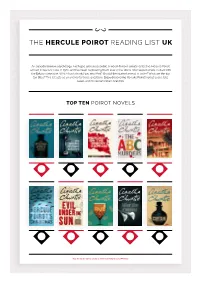

The Hercule Poirot Reading List Uk

THE HERCULE POIROT READING LIST UK An expert in human psychology. A refugee and an eccentric. A world-famous private detective. Hercule Poirot arrived in readers’ lives in 1920, and has been captivating them ever since. We’re often asked where to start with the Belgian detective. Which book should you read first? Should the stories be read in order? What are the top ten titles? This list acts as an answer to these questions. Enjoy discovering Hercule Poirot’s great cases, late cases, and his lesser known ones too. TOP TEN POIROT NOVELS Rate the top ten stories and let us know your thoughts using #Poirot10 THE GUIDE THE LIST Sometimes Poirot’s previous cases are referenced in Bearing in mind the guide on the left, it is possible to read the Poirot other books. For those looking to avoid spoilers we’d stories in any order. If you want to consider them chronologically (in make the following suggestions: terms of Poirot’s lifetime), we recommend the following: If you’re going to read all the stories, you can read The Mysterious Affair at Styles [1920] Curtain last The Murder on the Links [1923] If you’re going to read 10 Poirot stories in your life, While the Light Lasts (UK Short Story Collection) [1997] make sure Curtain is one of them Poirot Investigates (Short Story Collection) [1924] Elephants Can Remember references plots Poirot’s Early Cases (Short Story Collection) [1974 from Five Little Pigs, Hallowe’en Party, and Mrs McGinty’s Dead, so if you are keen to spot these, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd [1926] read the other three first.