The Fryent Country Park Story – Part 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aylsham Town 7 Miles Circular Walk

AYLSHAM TOWN 7 miles Aylsham is full of historic interest. The bustling market town bristles with charming features, including the John Soame Memorial Pump and The Black Boys coaching Inn, welcoming visitors today as it has for centuries. Humphry Repton (1752-1818), the famous landscape gardener, chose Aylsham as his final resting place. Sheringham Park, which Repton described as his ‘most favourite work’, is managed by The National Trust who are, coincidentally, Lords of the Manor of Aylsham and own Aylsham Market Place. You’ll pass Aylsham Staithe; opened in 1779 it was once the main artery to Aylsham’s agricultural industry. At its peak it carried over 1000 boats annually; mainly Norfolk wherries. The junction of river and roads, plus later railways, are crucial to the situation and importance of the town. Aylsham North, a Great Eastern Railway station, opened in 1883 only a short distance from the staithe. It quickly out-competed wherries for transporting freight. Devastating floods in 1912 destroyed bridges and locks, causing Aylsham Staithe’s final demise. The flood caused problems on the railway too. Over 200 people were stranded overnight after a train from Great Yarmouth was trapped at Aylsham North following multiple bridge collapses. Spa Lane, to the south of Aylsham, is named after the spa that existed there in the early 1700s. The mineral rich waters were considered good for health. Spa Lane can become muddy in winter. The alternative route shown, using another section along Marriott’s Way, offers a shorter, but drier, walk. A Norfolk Wherry moored at the water mill at Aylsham Staithe. -

Architecture MPS

Architecture_MPS Landscape and Consumer Culture in the Design Work of Humphry Repton and Gordon Cullen: A Methodological Framework Mira Engler*,1 How to cite: Engler, M. ‘Landscape and Consumer Culture in the Design Work of Humphry Repton and Gordon Cullen: A Methodological Framework.’ Architecture_MPS, 2018, 13(1): 2. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14324/111.444.amps.2018v13i2.001. Published: 09 March 2018 Peer Review: This article has been peer reviewed through the journal’s standard double blind peer-review, where both the reviewers and authors are anonymised during review. Copyright: © 2017, The Author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY) 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited • DOI: https://doi.org/10.14324/111.444.amps.2018v13i2.001. Open Access: Architecture_MPS is a peer-reviewed open access journal. *Correspondence: [email protected] 1 Iowa State University, USA Amps Title: Landscape and Consumer Culture in the Design Work of Humphry Repton and Gordon Cullen: A Methodological Framework Author: Mira Engler Architecture_media_politics_society. vol. 13, no. 2. March 2018 Affiliation: Landscape Architecture, Iowa State University Abstract The practice of landscape and townscape or urban design is driven and shaped by consumer markets as much as it is by aesthetics and design values. Since the 1700s gardens and landscapes have performed like idealized lifestyle commodities via attractive images in mass media as landscape design and consumer markets became increasingly entangled. This essay is a methodological framework that locates landscape design studies in the context of visual consumer culture, using two examples of influential and media-savvy landscape designers: the renowned eighteenth-century English landscape gardener Humphry Repton and one of Britain’s top twentieth-century draftsmen and postwar townscape designers, Gordon Cullen. -

The Surprising Discretion of Soane and Repton’, the Georgian Group Journal, Vol

Gillian Darley, ‘The surprising discretion of Soane and Repton’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. XII, 2002, pp. 38–47 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 2002 THE SURPRISING DISCRETION OF SOANE AND REPTON GILLIAN DARLEY y , the year in which Humphry Repton in March and completed in May , Repton was all Bswung from a life spent variously as essayist, too frank. Continuing his comments on the approach private secretary and Norwich-based commercial he finished with a tart and mischievous criticism of entrepreneur into his engrossing and successful new Soane’s additions to an earlier house: profession as a landscape gardener , John Soane was The proportions of the house are not pleasing, it already a firmly established country house architect, appears too high for its width, even where seen at an with much of his practice in Norfolk. angle presenting two fronts; and the heaviness of a Despite their rather differing clienteles, it was dripping roof always takes from the elegance of any inevitable that their paths would cross from time to building above the degree of a farm house; it would not be attended with great expence to add a blocking time. Among locations on which both worked were course to the cornice, and this with a white string Mulgrave Castle, Moggerhanger House, Aynhoe course under the windows, would produce such Park, Holwood House and Honing Hall. Generally horizontal lines as might in some measure counteract Repton would be brought in a year or two after the too great height of the house. There are few cases Soane’s building or rebuilding works were complete where I should prefer a red house to a white one, but and, within the covers of the Red Book which usually that at Honing is so evidently disproportioned, that we can only correct the defects by difference of colour, resulted from the visit, would feel free to criticise while in good Architecture all lines should depend on what he found. -

University Microfilms 300 North Zaeb Road Ann Arbor

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Download (Pdf, 107

Restoration of ponds in a landscape and changes in Common frog (Rana temporaria) populations, 1983–2005 L. R. WILLIAMS Brent Council, Parks Service, 660 Harrow Road, Wembley, Middlesex HA0 2HB, UK. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT – Monitoring of a population of the Common frog (Rana temporaria) was undertaken between 1983-2005 by annual counts of frogspawn during a pond restoration programme at the 103 ha Fryent Country Park, London, UK. Pond restoration, creation and management since 1983 resulted in a landscape with 31 water-bodies by 2005, though not all of these were suitable for breeding by frogs. Generally, smaller water-bodies were more prone to drying-up in dry seasons. Total annual frogspawn increased from 40 clumps in 1983 to a maximum of over 1,850 clumps. Populations of the Common frog appeared to respond to the pond restoration programme, though the quantity of frogspawn was also influenced by other, in particular, weather-related factors. There was a strong correlation between the size of ponds during the winter and the average spawn laid in available ponds. The quantity of frogspawn was strongly correlated with the number of ponds at the time of spawning and at the time of spawning in the previous year; and with the number of water holding ponds during the previous summer. ECLINES in the populations of the Common METHODS Dfrog from ponds and the countryside of Study area lowland England as a result of habitat loss has been Fryent Country Park is a 103 ha Local Nature noted by e.g. Beebee (1983), Baker & Halliday Reserve of lowland countryside, formerly in the (1999). -

What Is Community Engagement?

COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT STRATEGY “ True regeneration is about creating a lasting legacy. This will only occur if the local community feels connected to the developer who helps shape where they live, work and visit.” Ash Patel Community Engagement Manager CONTENTS 4 Aim of the strategy 5 Our vision 7 Community Initiative Research Report 9 What is community engagement? 12 Programme 13 Methodology 15 Community engagement 17 Outreach 20 Audiences 21 The Yellow’s project partners 23 Governance 23 Monitoring and evaluation 25 Enjoying The Yellow The Yellow COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT STRATEGY AIM OF THE STRATEGY Wembley Park’s community engagement strategy aims to foster a vibrant and happy community at Wembley Park by bringing together existing and new residents, workers, students and local groups through a robust, balanced and accessible programme. The Yellow’s strategy will evolve as Wembley Park develops and the number of residents increases. 4 The Yellow COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT STRATEGY PEOPLE MAKE A PLACE COME TO LIFE, THEY CREATE WARMTH OUR VISION AND OWNERSHIP. A SUCCESSFUL COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT PROGRAMME WILL ENCOURAGE PEOPLE TO FEEL POSITIVE ABOUT WEMBLEY PARK AS WELL AS MAKING THEM PART OF THE EXCITING JOURNEY. COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT IS KEY TO THE SUCCESS OF WEMBLEY PARK’S VISION LISTENING POSITIVITY TEAMWORK SUSTAINABILITY CONNECTIONS Organising activities Supporting the Promoting and Focusing on the Working to provide to fulfil requests by borough to develop supporting community long term viability access and links the community voiced positive identity led projects, of The Yellow and to our partners through feedback and create a offering volunteering creating a space to harness the skills of forms, surveys and cohesive community opportunities and for years to come. -

The Creation of Sheringham Park 1804-1839

BEFORE THE RHODODENDRONS: the creation of Sheringham Park 1804-1839 The National Trust is one of our ‘Useful Links’, or you can reach their details about Sheringham Park directly from here: https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/sheringham-park Now, thousands of visitors are attracted by the extensive plantings of rhododendrons (not introduced until the early 1850s), expansive parkland and views of the sea; but Humphry Repton, the self-styled ‘landscape gardener’ largely responsible for Sheringham Park, would have been mortified at the thought of what he called ‘felicity hunters’ being within striking distance of ‘The Bower’ (now known as Sheringham Hall, a private residence). The only visitors he aimed to please were those invited by the estate owner who, from October 1811, was Mr Abbott Upcher. But the transformation of the land to make his scheme possible began seven years before that, and the whole story covers thirty-five years. Thanks to the collection of Repton family papers held by Norfolk Record Office, it is possible to unpick the ‘improvement’ and have a privileged view of the intrigue behind this lengthy scheme. In 1804 the estate, comprising a modest farmhouse, manorial rights and 1074 acres of land, was surveyed with a view to sale by its owner, Mr Cook Flower. One of Humphry Repton’s sons, William, was a solicitor practising with his uncle in Aylsham and acted as Mr Flower’s agent. His advice to Mr Flower was that the estate would be worth considerably more if he inclosed the common land. He was well-placed to give this advice because his firm, Adey Repton & Co., undertook many local inclosure schemes thanks to streamlined legislation that allowed local commissioners to be appointed. -

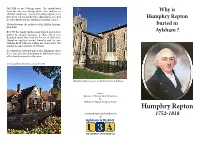

Why Is Humphry Repton Buried in Aylsham

Old Hall on the Felbrigg estate. The family lived there for ten years during which time another six Why is children were born. Young John Adey Repton must have been a clever lad because although he was deaf Humphry Repton he was educated at the Aylsham Grammar School. He later became the architect of the Hall in Shering- buried in ham Park. By 1786 the family fortunes had waned and so they Aylsham ? moved to cheaper premises in Hare Street near Romford where they lived for the rest of their lives. Humphry regularly visited Dorothy and his son, William lived with her, calling her ‘Aunt Adey.’ His brother became a farmer at Oxnead. In conclusion, it would appear that Humphry chose to be buried in the churchyard in Aylsham because of his family network in the town. Site of Aylsham Grammer School in 1785 Humphry Repton’s grave, St Michaels Church Aylsham Source Aylsham: A Nest of Norfolk Lawyers by William & Maggie Vaughan-Lewis Humphry Repton A research paper by Geraldine Lee of 1752-1818 Aylsham & District THE UNIVERSITY OF THE THIRD AGE Why is Humphry Repton buried in Aylsham when he never lived here? Humphry never spelt his name in the usual way His sister, Dorothy, had babies in 1771 and 1772 but with an ‘e.’ His clever father originally came from both died and were laid to rest in Aylsham Parish Lichfield before moving to Bury St Edmunds when Church and there were to be no more children. The he was 22 years old. couple continued to live in the house until they died. -

Entangled Colonial Landscapes and the 'Dead Silence'? : Humphry Repton, Jane Austen and the Upchers of Sheringham Park, Norfolk

This is a repository copy of Entangled colonial landscapes and the 'dead silence'? : Humphry Repton, Jane Austen and the Upchers of Sheringham Park, Norfolk. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/98119/ Version: Submitted Version Article: Finch, Jonathan Cedric orcid.org/0000-0003-2558-6215 (2014) Entangled colonial landscapes and the 'dead silence'? : Humphry Repton, Jane Austen and the Upchers of Sheringham Park, Norfolk. Landscape Research. pp. 82-99. ISSN 1469-9710 https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2013.848848 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 1 Entangled Landscapes and the ‘dead silence’? Humphry Repton, Jane Austen and the Upchers of Sheringham Park, Norfolk. Jonathan Finch, University of York, UK Abstract This paper explores two aspects of designed landscapes in the late-eighteenth and early- nineteenth centuries that are often neglected – first, the importance derived from intersecting (auto)biographies of designers and patrons, and, secondly, how they relate to global social, economic and political networks. -

Fifty Fabulous Features Download

‘Fifty Fabulous Features’ Statements of Significance for Fifty Features of Historic Designed Landscapes within the Land of the Fanns 1 Table of Contents Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................................... 4 Maps: .................................................................................................................................................... 14 FEATURE NAME (ID: 18): OLD HALL POND .................................................................................... 19 FEATURE NAME (ID: 24): GARDEN WALLS AND GATEWAYOF LITTLE BELHUS HOUSE ..................... 24 A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE BELHUS PARK TUDOR AND JACOBEAN GARDENS WITH REFERENCE TO THE INDIVIDUAL FEATURES THAT FOLLOW ...................................................................................... 28 FEATURE NAME (ID: 31): BELHUS PARK – REMAINS OF TUDOR/JACOBEAN GARDEN CANALS ....... 31 FEATURE NAME (ID: 33): REMAINS OF A CIRCULAR TUDOR/STUART GARDEN FEATURE, BELHUS PARK .................................................................................................................................................. 36 FEATURE NAME (ID: 30): BELHUS PARK - REMAINS OF MID-EIGHTEENTH CENTURY WALL OF WALLED GARDEN .............................................................................................................................. 41 FEATURE NAME (ID: 27): BELHUS PARK - LONG POND .................................................................... 47 FEATURE -

Autumn 2018 Magazinethe No.26

Autumn 2018 MagazineThe No.26 norfolkgt.org.uk 1 Contents Chairman’s Report ................................................................................1 Alicia Amherst - The Well-Connected Gardener - Sue Minter ............2 An Amateur’s Garden - Jan Michalak ...................................................6 Renovating Horsford Hall Greenhouse - David Pulling & Paul Clarke .......................................................................................10 Reviving the Medlar, our forgotten fruit - Jane Steward .......................14 Restoring a Twenties Gem - Alison Hall ...............................................18 Our Roundup of Repton 200 - Sally Bate .............................................22 Repton: The Prophet in his own Country - Margaret Anderson ..........24 NGT at the Museum – the Repton Sketches go Public - Sally Bate ....28 The NGT’s 30th Birthday Party ...........................................................32 Readers’ Garden: The Garden Room - Hingham .................................34 Book Reviews .........................................................................................35 Sally Bate Honoured ..............................................................................37 Obituary - Martin Walton .....................................................................38 Dates for Your Diary ..............................................................................39 Membership Matters ..............................................................................40 Cover: Reader’s -

Those Arts Which Have Given Celebrity to the Name

of patronage and I have no doubt of his acquitting himself to ‘Those Arts which have given your satisfaction’.5 celebrity to the name of Repton’ Among the surviving papers recording George’s work are two books of drawings compiled during his time with Nash The work of George Stanley which give an idea of the quality and scope of his work and the broad repertoire of styles to which he was exposed in Repton in Devon Nash’s office.6 In addition, the Royal Institute of British Architects holds a number of George Repton’s drawings Rosemary Yallop which can be identified with specific commissions, including those in Devon.7 In the commemorations of the bicentenary of the death of Humphry Repton in 2018 his work as an architect rather Through Nash George met his future wife, Lady Elizabeth than as a landscape designer was perhaps understandably Scott, as they were both frequent guests at East Cowes underplayed. The careers of his two architect sons, John Castle, Nash’s house on the Isle of Wight. Elizabeth’s father, Adey and George Stanley, have been noted largely in relation Lord Eldon, the Lord Chancellor, strongly disapproved of to their collaborations with their father, overshadowing the liaison on the grounds of George’s lower social rank, their independent work, although studies have been made but the couple nevertheless married in 1817. Whatever Nash of George’s work while in the office of John Nash.1 Yet thought of this (and he was said to have disapproved) George Humphry had been ambitious for his sons and had hoped continued to work for him for another three years until 1820, to create a dynasty of successful practitioners of landscape when he set up in practice independently, which seems to and architectural design employing complementary skills.