The Open Games with Black

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sample Pages

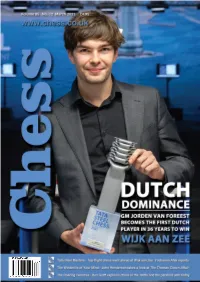

01-01 Cover -March 2021_Layout 1 17/02/2021 17:19 Page 1 03-03 Contents_Chess mag - 21_6_10 18/02/2021 09:47 Page 3 Chess Contents Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Editorial....................................................................................................................4 Editors: Richard Palliser, Matt Read Malcolm Pein on the latest developments in the game Associate Editor: John Saunders Subscriptions Manager: Paul Harrington 60 Seconds with...Jorden van Foreest.......................................................7 Twitter: @CHESS_Magazine We catch up with the man of the moment after Wijk aan Zee Twitter: @TelegraphChess - Malcolm Pein Website: www.chess.co.uk Dutch Dominance.................................................................................................8 The Tata Steel Masters went ahead. Yochanan Afek reports Subscription Rates: United Kingdom How Good is Your Chess?..............................................................................18 1 year (12 issues) £49.95 Daniel King presents one of the games of Wijk,Wojtaszek-Caruana 2 year (24 issues) £89.95 3 year (36 issues) £125 Up in the Air ........................................................................................................21 Europe There’s been drama aplenty in the Champions Chess Tour 1 year (12 issues) £60 2 year (24 issues) £112.50 Howell’s Hastings Haul ...................................................................................24 3 year (36 issues) £165 David Howell ran -

2009 U.S. Tournament.Our.Beginnings

Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis Presents the 2009 U.S. Championship Saint Louis, Missouri May 7-17, 2009 History of U.S. Championship “pride and soul of chess,” Paul It has also been a truly national Morphy, was only the fourth true championship. For many years No series of tournaments or chess tournament ever held in the the title tournament was identi- matches enjoys the same rich, world. fied with New York. But it has turbulent history as that of the also been held in towns as small United States Chess Championship. In its first century and a half plus, as South Fallsburg, New York, It is in many ways unique – and, up the United States Championship Mentor, Ohio, and Greenville, to recently, unappreciated. has provided all kinds of entertain- Pennsylvania. ment. It has introduced new In Europe and elsewhere, the idea heroes exactly one hundred years Fans have witnessed of choosing a national champion apart in Paul Morphy (1857) and championship play in Boston, and came slowly. The first Russian Bobby Fischer (1957) and honored Las Vegas, Baltimore and Los championship tournament, for remarkable veterans such as Angeles, Lexington, Kentucky, example, was held in 1889. The Sammy Reshevsky in his late 60s. and El Paso, Texas. The title has Germans did not get around to There have been stunning upsets been decided in sites as varied naming a champion until 1879. (Arnold Denker in 1944 and John as the Sazerac Coffee House in The first official Hungarian champi- Grefe in 1973) and marvelous 1845 to the Cincinnati Literary onship occurred in 1906, and the achievements (Fischer’s winning Club, the Automobile Club of first Dutch, three years later. -

Tidskrift För

Familjen Cramling: Anna & Dan Havanna 1966 – vad är myt, vad är sant? Alexei Shirov Mästerskap: blinda, döva, veteraner, nordbor & amatörer Nr 3 l 2017 TIDSKRIFT FÖR SCHACK-SM Hans Tikkanen för fjärde gången – då blir det svårare att lägga av Tidskrift för Schack MANUS ULF BILLQVIST & AXEL SMITH ILLUSTRATION ULF BILLQVIST INNEHÅLL # 3 – 2017 6 En passant Historien bakom världens vackraste drag. 8 Tepe Sigeman & Co Chess Tournament 9 Cellavision Chess Cup 10 Lag-VM för veteraner Historiens tredje svenska brons! 11 EM för döva 11 12 OS för synskadade 14 Nordiska Mästerskapen 15 VM för amatörer 12 16 SCHACK-SM 18 Intervju med Hans Tikkanen 20 Tikkanens paradnummer Tiger Hillarp om Sverigemästarklassen. 30 Schackfyranmästaren WASA SCHACKKLUBB 100 ÅR & Sveriges Schackförbund bjuder in till 32 Ungdomssidorna SM I SNABBSCHACK Fyra nya svenska mästare. 36 Havanna 1966 WASA SK SVENSKT MÄSTERSKAP I SNABBSCHACK! Vad är myt och vad är sanning? 40 Stjärnskott WSK Anna Cramling i föräldrarnas fotspår. 19 17 HASSELBACKEN 44 Vart tog de vägen? JUBILEE TOURNAMENT Dan Cramling i Brasilien. 100 YEARS 16–17 SEPTEMBER 2017 18 AVBROTT VI KOMMER! KOMMER DU? 48 Samtal Oskar von Bahr konkurrerar med proffsen. 49 Förbundsnytt 50 Skolschack 36 52 Schackhistoriska strövtåg GM Blomqvist SM-pokalen och 135-årig lagmatch. GM Hammer GM Grandelius 55 Kombinera med Tikkanen 56 Lösningar GM Cramling 57 Lång rockad Anmäl dig på hasselbackenwasa.se FOTO: LARS OA HEDLUND Shirov spelar som ställningen kräver. Tre klasser: Öppen, Veteran 50+ & Veteran 65+ 58 Försegling TfS #3 3 2017 MOREEVEN WORLD MORE PRESS WORLD CHESSPRESS OPEN EVEN MOREGERMANY HASSELBACKEN CANADA USA CHESSBASE.COMHASSELBACKENWORLD CHESSPRESS OPEN HASSELBACKENOPENCHESS OPEN MORE WORLDAP STO PRESS...och nu som en del av Svenskt Grand Prix Psst, vi är tillbaka.. -

Chess Openings

Chess Openings PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Tue, 10 Jun 2014 09:50:30 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 Chess opening 1 e4 Openings 25 King's Pawn Game 25 Open Game 29 Semi-Open Game 32 e4 Openings – King's Knight Openings 36 King's Knight Opening 36 Ruy Lopez 38 Ruy Lopez, Exchange Variation 57 Italian Game 60 Hungarian Defense 63 Two Knights Defense 65 Fried Liver Attack 71 Giuoco Piano 73 Evans Gambit 78 Italian Gambit 82 Irish Gambit 83 Jerome Gambit 85 Blackburne Shilling Gambit 88 Scotch Game 90 Ponziani Opening 96 Inverted Hungarian Opening 102 Konstantinopolsky Opening 104 Three Knights Opening 105 Four Knights Game 107 Halloween Gambit 111 Philidor Defence 115 Elephant Gambit 119 Damiano Defence 122 Greco Defence 125 Gunderam Defense 127 Latvian Gambit 129 Rousseau Gambit 133 Petrov's Defence 136 e4 Openings – Sicilian Defence 140 Sicilian Defence 140 Sicilian Defence, Alapin Variation 159 Sicilian Defence, Dragon Variation 163 Sicilian Defence, Accelerated Dragon 169 Sicilian, Dragon, Yugoslav attack, 9.Bc4 172 Sicilian Defence, Najdorf Variation 175 Sicilian Defence, Scheveningen Variation 181 Chekhover Sicilian 185 Wing Gambit 187 Smith-Morra Gambit 189 e4 Openings – Other variations 192 Bishop's Opening 192 Portuguese Opening 198 King's Gambit 200 Fischer Defense 206 Falkbeer Countergambit 208 Rice Gambit 210 Center Game 212 Danish Gambit 214 Lopez Opening 218 Napoleon Opening 219 Parham Attack 221 Vienna Game 224 Frankenstein-Dracula Variation 228 Alapin's Opening 231 French Defence 232 Caro-Kann Defence 245 Pirc Defence 256 Pirc Defence, Austrian Attack 261 Balogh Defense 263 Scandinavian Defense 265 Nimzowitsch Defence 269 Alekhine's Defence 271 Modern Defense 279 Monkey's Bum 282 Owen's Defence 285 St. -

Floridachess Summer 2019

Summer 2019 GM Olexandr Bortnyk wins the 26th Space Coast Open FCA BOARD OF DIRECTORS [term till] kqrbn Contents KQRBN President Kevin J. Pryor (NE) [2019] Editor Speaks & President’s Message .................................................................... 3 Jacksonville, FL [email protected] FCA’s Membership Growth .......................................................................................... 4 FCA Elections ....................................................................................................................... 4 Vice President Ukrainian Takes Over Space Coast Open by Peter Dyson .................................. 5 Stephen Lampkin (NE) [2019] Port Orange, FL Space Coast Open Brilliancy Prize winners by Javad Maharramzade .............. 5 [email protected] 2019 CFCC Sunshine Open by Steven Vigil ............................................................... 10 by Miguel Ararat ................................................. Secretary Some games from recent events 12 Bryan Tillis (S) [2019] A game from the 26th Space Coast Open ............................................................. 16 West Palm Beach, FL Meet the Candidates .........................................................................................................19 [email protected] 2019 FCA Voting Procedures .......................................................................................19 Treasurer 2019 Queen’s Cup Challenge by Kevin Pryor .............................................................. 20 Scott -

Tfs 4/2011 3 Nummer 4 2011

Tidskrift för Schack Nummer 4/2011 TfS Årgång 117 Guldjubel i Albena Nils Grandelius vann Ungdoms-EM Ekonomin i fokus inför 2012 Höstsäsongen är nästan slut och får vi räkna med, om inte den schackverksamheten går på högfart negativa utvecklingen på riksnivå ute i landet. För styrelsen är vintern bromsas. Mer information om hur som vanligt en intensiv period, med framtiden när det gäller bidrag ser budgetarbetet inför kommande ut för SSF:s klubbar och distrikt år högst upp på dagordningen. kommer att presenteras på www. En del arbete återstår, men det schack.se. står redan klart att vi är tvungna att fortsätta på den tidigare linjen En åtgärd som vi genomförde med ytterligare åtstramningar. redan under 2011 var en minskning Det beror dels på att vi väntar oss av Schackfyrans centrala resurser. en ytterligare minskning av de statliga bidragen, Det uttrycktes då farhågor för hur projektet skulle dels på en uttalad ambition från styrelsens sida att klara sig utan en heltidsanställd projektledare, men stärka det egna kapitalet. även om det är för tidigt att säga något definitivt, är Vi har de senaste åren investerat hårt i de indikationerna än så länge positiva. Vi har redan centrala projekten Schackfyran och Schack i nu dragit igång Schackfyranverksamhet i flera nya skolan, vilket har resulterat i kraftigt ökande distrikt och i flera andra distrikt ser det ut som om medlemstal. Utan de här projekten hade vi verksamheten kommer att växa. Sluträkningen naturligtvis drabbats betydligt hårdare än vi nu sker först efter riksfinalen 2012, som äger rum 2 har gjort av de försämrade statliga bidragen, men juni i Västerås, men än så länge ser det alltså ljust dessa långsiktiga satsningar har också på kort sikt ut. -

Chess Mag - 21 6 10 18/09/2020 14:01 Page 3

01-01 Cover - October 2020_Layout 1 18/09/2020 14:00 Page 1 03-03 Contents_Chess mag - 21_6_10 18/09/2020 14:01 Page 3 Chess Contents Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Editorial....................................................................................................................4 Editors: Richard Palliser, Matt Read Malcolm Pein on the latest developments in the game Associate Editor: John Saunders Subscriptions Manager: Paul Harrington 60 Seconds with...Peter Wells.......................................................................7 Twitter: @CHESS_Magazine The acclaimed author, coach and GM still very much likes to play Twitter: @TelegraphChess - Malcolm Pein Website: www.chess.co.uk Online Drama .........................................................................................................8 Danny Gormally presents some highlights of the vast Online Olympiad Subscription Rates: United Kingdom Carlsen Prevails - Just ....................................................................................14 1 year (12 issues) £49.95 Nakamura pushed Magnus all the way in the final of his own Tour 2 year (24 issues) £89.95 Find the Winning Moves.................................................................................18 3 year (36 issues) £125 Can you do as well as the acclaimed field in the Legends of Chess? Europe 1 year (12 issues) £60 Opening Surprises ............................................................................................22 2 year (24 issues) £112.50 -

Sample Pages

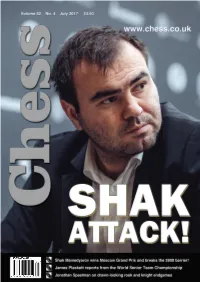

01-01 July Cover_Layout 1 18/06/2017 21:25 Page 1 02-02 NIC advert_Layout 1 18/06/2017 19:54 Page 1 03-03 Contents_Chess mag - 21_6_10 18/06/2017 20:32 Page 3 Chess Contents Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Editorial.................................................................................................................4 Editors: Richard Palliser, Matt Read Malcom Pein on the latest developments in the game Associate Editor: John Saunders Subscriptions Manager: Paul Harrington 60 Seconds with...John Bartholomew....................................................7 We catch up with the IM and CCO of Chessable.com Twitter: @CHESS_Magazine Twitter: @TelegraphChess - Malcolm Pein Not a Classic .......................................................................................................8 Website: www.chess.co.uk Steve Giddins wasn’t overly taken with the Moscow Grand Prix Subscription Rates: How Good is Your Chess? ..........................................................................11 United Kingdom Daniel King features a game from the in-form Mamedyarov 1 year (12 issues) £49.95 2 year (24 issues) £89.95 Bundesliga Brilliance.....................................................................................14 3 year (36 issues) £125 Matthew Lunn presents two creative gems from the Bundesliga Europe 1 year (12 issues) £60 Find the Winning Moves .............................................................................18 2 year (24 issues) £112.50 Can you do as well as some leading -

Owen Mccoy on the Front Cover: Northwest Chess US Chess Master Owen Mccoy

orthwes $3.95 N t C h May 2018 e s s Chess News and Features from Oregon, Washington, and Idaho Owen McCoy On the front cover: Northwest Chess US Chess Master Owen McCoy. (See story pp. 4-7.) May 2018, Volume 72-05 Issue 844 Photo credit: Sarah McCoy. ISSN Publication 0146-6941 Published monthly by the Northwest Chess Board. On the back cover: POSTMASTER: Send address changes to the Office of Record: GM Julio Sadorra doing a pushup at Kerry Park on Northwest Chess c/o Orlov Chess Academy 4174 148th Ave NE, Queen Anne overlooking downtown Seattle. (Don’t try Building I, Suite M, Redmond, WA 98052-5164. this at home, kids!) Photo credit: Jacob Mayer. Periodicals Postage Paid at Seattle, WA USPS periodicals postage permit number (0422-390) Chesstoons: Chess cartoons drawn by local artist Brian Berger, NWC Staff of West Linn, Oregon. Editor: Jeffrey Roland, [email protected] Games Editor: Ralph Dubisch, [email protected] Submissions Publisher: Duane Polich, [email protected] Submissions of games (PGN format is preferable for games), Business Manager: Eric Holcomb, stories, photos, art, and other original chess-related content [email protected] are encouraged! Multiple submissions are acceptable; please indicate if material is non-exclusive. All submissions are Board Representatives subject to editing or revision. Send via U.S. Mail to: David Yoshinaga, Josh Sinanan, Jeffrey Roland, NWC Editor Jeffrey Roland, Adam Porth, Chouchanik Airapetian, 1514 S. Longmont Ave. Brian Berger, Duane Polich. Boise, Idaho 83706-3732 or via e-mail to: Entire contents ©2018 by Northwest Chess. All rights reserved. -

YEARBOOK the Information in This Yearbook Is Substantially Correct and Current As of December 31, 2020

OUR HERITAGE 2020 US CHESS YEARBOOK The information in this yearbook is substantially correct and current as of December 31, 2020. For further information check the US Chess website www.uschess.org. To notify US Chess of corrections or updates, please e-mail [email protected]. U.S. CHAMPIONS 2002 Larry Christiansen • 2003 Alexander Shabalov • 2005 Hakaru WESTERN OPEN BECAME THE U.S. OPEN Nakamura • 2006 Alexander Onischuk • 2007 Alexander Shabalov • 1845-57 Charles Stanley • 1857-71 Paul Morphy • 1871-90 George H. 1939 Reuben Fine • 1940 Reuben Fine • 1941 Reuben Fine • 1942 2008 Yury Shulman • 2009 Hikaru Nakamura • 2010 Gata Kamsky • Mackenzie • 1890-91 Jackson Showalter • 1891-94 Samuel Lipchutz • Herman Steiner, Dan Yanofsky • 1943 I.A. Horowitz • 1944 Samuel 2011 Gata Kamsky • 2012 Hikaru Nakamura • 2013 Gata Kamsky • 2014 1894 Jackson Showalter • 1894-95 Albert Hodges • 1895-97 Jackson Reshevsky • 1945 Anthony Santasiere • 1946 Herman Steiner • 1947 Gata Kamsky • 2015 Hikaru Nakamura • 2016 Fabiano Caruana • 2017 Showalter • 1897-06 Harry Nelson Pillsbury • 1906-09 Jackson Isaac Kashdan • 1948 Weaver W. Adams • 1949 Albert Sandrin Jr. • 1950 Wesley So • 2018 Samuel Shankland • 2019 Hikaru Nakamura Showalter • 1909-36 Frank J. Marshall • 1936 Samuel Reshevsky • Arthur Bisguier • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1953 Donald 1938 Samuel Reshevsky • 1940 Samuel Reshevsky • 1942 Samuel 2020 Wesley So Byrne • 1954 Larry Evans, Arturo Pomar • 1955 Nicolas Rossolimo • Reshevsky • 1944 Arnold Denker • 1946 Samuel Reshevsky • 1948 ONLINE: COVID-19 • OCTOBER 2020 1956 Arthur Bisguier, James Sherwin • 1957 • Robert Fischer, Arthur Herman Steiner • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1954 Arthur Bisguier • 1958 E. -

Calle Erlandsson CHESS PERIODICAL WANTS LIST Nyckelkroken 14, SE-22647 Lund Updated 20.7 2019 [email protected] Cell Phone +46 733 264 033

Calle Erlandsson CHESS PERIODICAL WANTS LIST Nyckelkroken 14, SE-22647 Lund updated 20.7 2019 [email protected] Cell phone +46 733 264 033 AUSTRIA ARBEITER-SCHACHZEITUNG [oct1921-sep1922; jan1926-dec1933; #12/1933 final issue?] 1921:1 2 3 1922:4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 1926:1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 1927:11 12 1928:2 3 4 5 8 9 10 11 12 1929:1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 INTERNATIONALE GALERIE MODERNER PROBLEM-KOMPONISTEN [jan1930-oct1930; #10 final issue] 1930:2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 KIEBITZ [1994->??] 1994:1 3-> NACHRICHTEN DES SCHACHVEREIN „HIETZING” [1931-1934; #3-4/1934 final issue?] 1931 1932:1 2 4 5 6 8 9 10 1933:4 7 1934:1 2 NÖ SCHACH [1978->] 1978 1979:1 2 4-> 1980-> ORAKEL [1940-19??; Das Magazin für Rätsel, Danksport, Philatelie, Schach und Humor, Wien; Editor: Maximilian Kraemer] 1940-1946 1947:1-4 6->? ÖSTERREICHISCHE LESEHALLE [1881-1896] 1881:1-12 1882:13-24 1883:25-36 1884:37-48 1885:49-60 1886 1887 1888 1889 1890 1891 1892 1893 1894 1895 1896 ÖSTERREICHISCHE SCHACHRUNDSCHAU [1922-1925] have a complete run ÖSTERREICHISCHE SCHACHZEITUNG [1872-1875 #1-63; 1935-1938; 1952-jan1971; #1/1971 final issue] 1872:1-18 1937:11 12 1938:2 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 SCHACH-AKTIV [1979->] 1979:3 4 2014:1-> SCHACH-MAGAZíN [1946-1951; superseded by Österreichische Schachzeitung] have a complete run WIENER SCHACHNACHRICHTEN [feb1992->?] 1992 1993 1994:1-6 9-12 1995:1-4 6-12 1996-> [Neue] WIENER SCHACHZEITUNG [jan1855-sep1855; jul1887-mar1888; jan1898-apr1916; mar1923- 1938; jul1948-aug1949] 1855:1-9 1887/88:1-9 1916:1/4© 5/8© Want publishers original bindings: 1898 1915 1938 BELARUS AMADEUS [1992->??; Zhurnal po Shakhmatnoij Kompozitzii] 1992-> SHAKHMATY, SHASJKI v BSSR [dec1979-oct1990] 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 SHAKHMATY [jun2004->; quarterly] 2003:1 2 2004:6 2006:11 13 14 2007:15 16 17 18 2008:19 20 21 22 2009->? SHAKHMATY-PLJUS [2003->; quarterly] 2003:1 2004:4 5 2005:6 7 8 9 2006:10-> BELGIUM [BULLETIN] A.J.E.C. -

Chess & Bridge

2013 Catalogue Chess & Bridge Plus Backgammon Poker and other traditional games cbcat2013_p02_contents_Layout 1 02/11/2012 09:18 Page 1 Contents CONTENTS WAYS TO ORDER Chess Section Call our Order Line 3-9 Wooden Chess Sets 10-11 Wooden Chess Boards 020 7288 1305 or 12 Chess Boxes 13 Chess Tables 020 7486 7015 14-17 Wooden Chess Combinations 9.30am-6pm Monday - Saturday 18 Miscellaneous Sets 11am - 5pm Sundays 19 Decorative & Themed Chess Sets 20-21 Travel Sets 22 Giant Chess Sets Shop online 23-25 Chess Clocks www.chess.co.uk/shop 26-28 Plastic Chess Sets & Combinations or 29 Demonstration Chess Boards www.bridgeshop.com 30-31 Stationery, Medals & Trophies 32 Chess T-Shirts 33-37 Chess DVDs Post the order form to: 38-39 Chess Software: Playing Programs 40 Chess Software: ChessBase 12` Chess & Bridge 41-43 Chess Software: Fritz Media System 44 Baker Street 44-45 Chess Software: from Chess Assistant 46 Recommendations for Junior Players London, W1U 7RT 47 Subscribe to Chess Magazine 48-49 Order Form 50 Subscribe to BRIDGE Magazine REASONS TO SHOP ONLINE 51 Recommendations for Junior Players - New items added each and every week 52-55 Chess Computers - Many more items online 56-60 Bargain Chess Books 61-66 Chess Books - Larger and alternative images for most items - Full descriptions of each item Bridge Section - Exclusive website offers on selected items 68 Bridge Tables & Cloths 69-70 Bridge Equipment - Pay securely via Debit/Credit Card or PayPal 71-72 Bridge Software: Playing Programs 73 Bridge Software: Instructional 74-77 Decorative Playing Cards 78-83 Gift Ideas & Bridge DVDs 84-86 Bargain Bridge Books 87 Recommended Bridge Books 88-89 Bridge Books by Subject 90-91 Backgammon 92 Go 93 Poker 94 Other Games 95 Website Information 96 Retail shop information page 2 TO ORDER 020 7288 1305 or 020 7486 7015 cbcat2013_p03to5_woodsets_Layout 1 02/11/2012 09:53 Page 1 Wooden Chess Sets A LITTLE MORE INFORMATION ABOUT OUR CHESS SETS..