UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sociolinguistic Analysis of Asian American English

Race and English Language 1 The Identity Behind Funny: Sociolinguistic Analysis of Contemporary Asian American Comedians An Analytical Research Study Jin Jo Jeanne Bohannon, Ph.D. Kennesaw State University Race and English Language 2 Abstract According to the United States Census Bureau, the U.S. population increased 9.7% from 2000 to 2010. Comparably, the population of Asian or Asian in combination in the U.S. has increased 45.6%. As people of minority races in the U.S. grow, so does the representation of them in popular culture and mass media. From ABC’s TV show Fresh Off the Boat to the generation of young Asian Americans starring in their own YouTube videos, a wave of Asian American linguistic presence in media is higher than ever before. In my research, I will discuss a close analysis of sociolinguistics connected to contemporary Asian American comedians in the media to provide perspective on their influence on the general public’s view of Asians. As Author Jess C. Scott states, “People are sheep. TV is the shepherd.” The media lays a foundation to the ideology of Asian Americans for the viewers. Introduction A simple conversation and occurrence catapulted my research into Asian American linguistics in media. I had a conversation with a Caucasian American friend of mine in which I asked him, “If you never met me and talked to me over the phone, would you know by my voice that I am a 30 year old Asian American woman?” He replied, “No, I would think you are a 17 year old white girl.” Another occurrence I recalled was when I attended high school in which a student sitting next to me cheated off my math test without my knowledge. -

Jimmy James About

JIMMY JAMES ABOUT The ONE & MANY VOICES of JIMMY JAMES - LIVE! AWARD WINNING ENTERTAINER! Singer-Songwriter of the global dance hit "FASHIONISTA" topping the BILLBOARD Dance Charts with OVER 20 MILLION VIEWS on YouTube from fan-made videos (from the album 'JAMESTOWN' on iTunes & Amazon). Jimmy James has worked with some of the world's best dance music producers including Chris Cox, Barry Harris, The Berman Brothers, IIO, Eric Kupper, Thomas Gold and more...most of whom have also produced and remixed for Cher, Madonna, Britney Spears, Whitney Houston - to name a few. In addition to being a recording artist, Jimmy James is an Award-Winning Entertainer known for his lively stunning musical cabaret shows featuring his Live Legendary Vocal Impressions. James, an ever-evolving Performance Artist, carries the legacy of his past as the world's greatest Marilyn Monroe impersonator. Although he retired his Marilyn act in 1997, his visual illusion of her is still considered the best there ever was. He garnered numerous national television appearances on the most popular talk shows of the 80s and 90s. By 1996 he landed on a giant Billboard in the center of Times Square as Marilyn Monroe, Judy Garland and Bette Davis with Supermodel Linda Evangelista. Additionally, his 1991 ad as Marilyn Monroe with horn-rimmed glasses for l.a. Eyeworks is passed "New York performance artist Jimmy James [song around the internet and copied repeatedly for tattoos and art galleries everywhere. The ad image shot by Greg Gorman may be THE most misidentified photo of Marilyn Fashionista] is so darn clever, it's hard not to offer Monroe ever. -

Services Transition, Stress, Anxiety, Toys, Etc

PUPPIES Australian Shep- SPRINKLER REPAIR Austin herd/Blue Lacy puppies ready Sprinkler Repair-Valve Re- for homes 7/10/2010. First pair/Rebuild Older Systems. garage/ shots, dewormed, vet check Call Del LI#14425 438-9144. done. Both boys and girls left. health/ Great for the ranch, agility, estate sales obedience or pet for the active family. Raised with kids, super wellness social. Dripping Springs. $50. buy/sell/trade MOVING SALE Sat 24 8-4 Call Becky (512)468-4869. HYPNOTHERAPY for life Furniture, TV-DVD, Clothes, services transition, stress, anxiety, Toys, etc. 1153 Dalea Bluff fear, conflict, motivation, labor RR, TX 78665 confidence, emotional well being. Private sessions. Central Austin. open2transformation.com clothing business (512) 551-4024 ROOF REPAIR Roof leaks & electronics tickets/en- creative Reroofs. * Insured * Member REIKI Let this gentle, nurtur- BBB * Call J-Conn Roofing & pets/pet ing and healing energy bring Repair. Call 512-479-0510 tertainment you renewal, relief from pain, and a feeling of peace and ACCEPTING DIGITAL CAMERA Sony CLOTHING Kill Shot Clothing BALLOON ARTIST Co. www.killshotgear.com Professional Clown/Balloon well-being. Central location. CONSIGNMENTS pmw-ex3 xdcam ex,only 55 supplies ALL Artist Austin and Central Texas Call Jennifer 331-8195. We will be taking formal, hours!!!Lens flawless!! Comes ADOPTION SAVE ONE DOG GAIN NATIONAL Creating smiles, memories costume & plus size with 8GB sxs memory card.Ad- STRESS RELEASE Alphabi- - SAVE THE WORLD! and fun!!:-)) Working with your women’s clothing beginning ditionally, the PMW-EX3 offers EXPOSURE Reach over 5 budget... http://www.jakeyth- otic Stress Release in Austin! a convenient remote-control Wanted: Super Homes for our million young, active, Alphabiotics is a scientifically July 24. -

Arts, Culture and Media 2010 a Creative Change Report Acknowledgments

Immigration: Arts, Culture and Media 2010 A Creative Change Report Acknowledgments This report was made possible in part by a grant from Unbound Philanthropy. Additional funding from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Ford Foundation, Four Freedoms Fund, and the Open Society Foundations supports The Opportunity Agenda’s Immigrant Opportunity initiative. Starry Night Fund at Tides Foundation also provides general support for The Opportunity Agenda and our Creative Change initiative. Liz Manne directed the research, and the report was co-authored by Liz Manne and Ruthie Ackerman. Additional assistance was provided by Anike Tourse, Jason P. Drucker, Frances Pollitzer, and Adrian Hopkins. The report’s authors greatly benefited from conversations with Taryn Higashi, executive director of Unbound Philanthropy, and members of the Immigration, Arts, and Culture Working Group. Editing was done by Margo Harris with layout by Element Group, New York. This project was coordinated by Jason P. Drucker for The Opportunity Agenda. We are very grateful to the interviewees for their time and willingness to share their views and opinions. About The Opportunity Agenda The Opportunity Agenda was founded in 2004 with the mission of building the national will to expand opportunity in America. Focused on moving hearts, minds, and policy over time, the organization works closely with social justice organizations, leaders, and movements to advocate for solutions that expand opportunity for everyone. Through active partnerships, The Opportunity Agenda uses communications and media to understand and influence public opinion; synthesizes and translates research on barriers to opportunity and promising solutions; and identifies and advocates for policies that improve people’s lives. -

“TERRIFICALLY ENGAGING.” – Variety

“TERRIFICALLY ENGAGING.” – Variety “BOBCAT GOLDTHWAIT’S MASTERPIECE. A TRULY BEAUTIFUL HUMAN DOCUMENT.” – Drew McWeeny, Hitfix 2015 CALL ME LUCKY a film by Bobcat Goldthwait CALL ME LUCKY is an inspiring, triumphant and wickedly funny documentary with a compelling and controversial hero at its heart. Barry Crimmins, best known as a comedian and political satirist, bravely tells his incredible story of transformation with intimate interviews from comedians such as David Cross, Margaret Cho and Patton Oswalt, activists such as Billy Bragg and Cindy Sheehan and directed in inimitable style by Bobcat Goldthwait (World’s Greatest Dad/God Bless America/Willow Creek). As a young and hungry comic in the early 80’s Barry Crimmins founded his own comedy club in Boston, in a Chinese restaurant called the Ding Ho. Here he fostered the careers of new talent who we now know as Steven Wright, Paula Poundstone, Denis Leary, Lenny Clarke, Kevin Meaney, Bobcat Goldthwait, Tom Kenny and many others. These comics were grateful for Barry’s fair pay and passionate support and respected him as a whip-smart comic himself but, as becomes clear in their interviews, they also knew he was tortured by his past. As archive footage of Barry shows, he was thickly mustachioed, thick set and thinly disguising an undercurrent of rage beneath his beer swilling onstage act. It seemed Barry was the fierce defender of the little guy but also an angry force when confronted. As one of the top new comedians in the country he appeared on The HBO Young Comedians Special, The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, Evening at the Improv and many other television shows in the 80’s. -

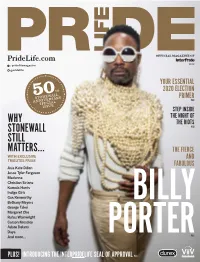

Why Stonewall Still Matters…

PrideLife Magazine 2019 / pridelifemagazine 2019 @pridelife YOUR ESSENTIAL th 2020 ELECTION 50 PRIMER stonewall P.68 anniversaryspecial issue STEP INSIDE THE NIGHT OF WHY THE RIOTS STONEWALL P.50 STILL MATTERS… THE FIERCE WITH EXCLUSIVE AND TRIBUTES FROM FABULOUS Asia Kate Dillon Jesse Tyler Ferguson Madonna Christian Siriano Kamala Harris Indigo Girls Gus Kenworthy Bethany Meyers George Takei BILLY Margaret Cho Rufus Wainwright Carson Kressley Adore Delano Daya And more... PORTERP.46 PLUS! INTRODUCING THE INTERPRIDELIFE SEAL OF APPROVAL P.14 B:17.375” T:15.75” S:14.75” Important Facts About DOVATO Tell your healthcare provider about all of your medical conditions, This is only a brief summary of important information about including if you: (cont’d) This is only a brief summary of important information about DOVATO and does not replace talking to your healthcare provider • are breastfeeding or plan to breastfeed. Do not breastfeed if you SO MUCH GOES about your condition and treatment. take DOVATO. You should not breastfeed if you have HIV-1 because of the risk of passing What is the Most Important Information I Should ° You should not breastfeed if you have HIV-1 because of the risk of passing What is the Most Important Information I Should HIV-1 to your baby. Know about DOVATO? INTO WHO I AM If you have both human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) and ° One of the medicines in DOVATO (lamivudine) passes into your breastmilk. hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, DOVATO can cause serious side ° Talk with your healthcare provider about the best way to feed your baby. -

Women in Comedy

WOMEN IN COMEDY BACKGROUND: MAKERS: Women In Comedy tracks the rise of women in the world of comedy, from the “dangerous” comedy of 70s sitcoms like Norman Lear’s Maude to the groundbreaking women of the 1980s American comedy club boom and building to today’s multifaceted landscape. Today, movies like Bridesmaids break box office records and the women of Saturday Night Live are often more famous than their male counterparts, but it didn’t start out that way. Early breakout female comics had to keep their jokes within the safe context of marriage, motherhood, and a man’s world. But they still found a way to be subversive. As Joan Rivers puts it, “I was furious about having to get married… It all comes out on stage. So that’s what I do onstage. I really tell them the truth.” Soon comedy became a vehicle for women to take on some of the most sensitive and controversial issues of the day. On television in the 1960s, entertainers like Carol Burnett and Mary Tyler Moore illuminated the core issues of feminism with humor that was both sly and truthful. But it took a powerful male producer to bring the most provocative feminist characters onto the screen. Maude, who Lear introduced to audiences in 1971, was a feminist firebrand on her fourth husband, strong and independent with a razor sharp wit. “When Maude was on the air,” Lear tells us, “I used to get letters from the First Lady, Betty Ford…. And she always signed every letter ‘Maude’s #1 fan’.” When Maude chose to have an abortion at 47, religious groups protested, but the episode was watched by 65 million Americans. -

Margaret Cho's Revoicings of Mock Asian

Pragmatics 14:2/3.263-289 (2004) International Pragmatics Association IDEOLOGIES OF LEGITIMATE MOCKERY: MARGARET CHO’S REVOICINGS OF MOCK ASIAN1 Elaine W. Chun Abstract This article examines a Korean American comedian’s use of Mock Asian and the ideologies that legitimate this racializing style. These ideologies of legitimacy depend on assumptions about the relationship between communities, the authentication of a speaker’s community membership, and the nature of the interpretive frame that has been “keyed”. Specifically, her Mock Asian depends on and, to some extent, reproduces particular ideological links between race, nation, and language despite the apparent process of ideological subversion. Yet her use of stereotypical Asian speech is not a straightforward instance of racial crossing, given that she is ‘Asian’ according to most racial ideologies in the U.S. Consequently, while her use of Mock Asian may necessarily reproduce mainstream American racializing discourses about Asians, she is able to simultaneously decontextualize and deconstruct these very discourses. This article suggests that it is her successful authentication as an Asian American comedian, particularly one who is critical of Asian marginalization in the U.S., that legitimizes her use of Mock Asian and that yields an interpretation of her practices primarily as a critique of racist mainstream ideologies. Keywords: Asian American, Race, Ideology, Humor, Performance 1. Introduction In elementary schoolyards across the U.S., children of perceived East Asian descent are reminded of their racial otherness through ostensibly playful renderings of an imagined variety of American English frequently referred to as a ‘Chinese accent’. This variety, which I call Mock Asian in this paper, is a discourse that indexes a stereotypical Asian identity. -

XM to Showcase Comedians Recorded Live from Famed Carolines on Broadway Comedy Nightclub in Times Square

NEWS RELEASE XM to Showcase Comedians Recorded Live from Famed Carolines on Broadway Comedy Nightclub in Times Square 9/30/2003 Nation's Premier Comedy Stage Produces Laughs for Nation's Leading Satellite Radio Service Washington D.C., September 30, 2003-- XM Satellite Radio, Inc. (NASDAQ: XMSR), the nation's number one satellite radio service, today announced it will begin broadcasting special comedy events recorded live the famed Carolines on Broadway comedy nightclub in New York City's Times Square starting in October on XM Comedy, Channel 150. XM will present these special concerts uncut and uncensored. "If you see someone in the car next to you sitting alone laughing their head off while stuck in traffic, it is a pretty good bet they're tuned into XM Comedy. Now, with the addition of the country's funniest comedians recorded live at Carolines, we fear we might actually make Americans look forward to traffic jams," said Sonny Fox, Program Director of XM's comedy channels. "But seriously, just as HBO brings the best, uncensored entertainment to people's televisions across America, XM Comedy is bringing the same unedited excitement to their radios by showcasing great live and compelling entertainment like Carolines on Broadway." Carolines on Broadway is America's premier comedy nightclub. Now celebrating its twentieth year, Carolines is one of the top live entertainment venues in New York City, showcasing the top comedians in the country seven nights a week. Carolines' stage has hosted such greats as Jay Leno, Jerry Seinfeld, Chris Rock, Janeane Garofalo, Jay Mohr, Drew Carey, Margaret Cho, Dave Chappelle, Kathy Griffin and Damon Wayans. -

Mary's Place 2020 SHINE Gala Goes Virtual with an Interactive, Live- Streamed Singing Competition and Live and Silent Auctions

Mary's Place 2020 SHINE Gala Goes Virtual with an Interactive, Live- Streamed Singing Competition and Live and Silent Auctions The event goal is to raise $1.5 million in one exciting night to benefit the Mary's Place Popsicle Place program for families with critically ill children who are experiencing homelessness Seattle (October 16, 2020) – Mary's Place 2nd annual SHINE Gala goes virtual this year and it promises to be even more engaging and interactive. Local singers and music artists will perform and compete for a winning title. Silent and live auctions will offer exclusive, one-of-a-kind items. This family-friendly, interactive show will be live- streamed at marysplaceseattle.org on Friday, October 23 from 6:30 to 8:30 pm. Registration is free at marysplaceshinegala.org. Guests are invited to drop in early, a 6:00 pm virtual preshow will feature a social media photo booth, a virtual wine tasting with Tinte Cellars, an auction preview, and a behind-the-scenes tour of the Microsoft Studios, all from the comfort of your living room! During this pandemic, when many are staying home to stay healthy, it’s more important than ever to ensure that families have safe, stable housing. Mary's Place is the leading provider of emergency shelter and services for women, families and children experiencing homelessness in Washington State. In 2019, Mary's Place helped over 750 families find their way back to a home of their own. The 2020 SHINE Gala raises critical funds for Mary's Place Popsicle Place program, which provides safety, medical services, and hope for families with medically fragile children. -

POP TRASH Anna Nicole Smith Nicole Anna

Cher Divine Amy Schumer Chris Rock Amy Sedaris Conan O’Brien Joan Rivers Lindsay Lohan Steve Jobs Anna Nicole Smith Phyllis Diller Elvis Presley Chelsea Handler Barbra Streisand Lady Gaga Barack Obama Tina Fey Willie Nelson Wendy Williams Benedict Cumberbatch Andy Cohen Margaret Cho Harry Styles David Lynch Big Freedia Charo Clint Eastwood Elvira Madonna Helen Gurley Brown Cyndi Lauper Nick Offerman Megan Mullally Albert Einstein Ricki Lake Andy Warhol Faye Dunaway The Go-Go’s Debbie Harry pop artalike. literally trashy—spotlights. requ work themeticulous into insights Funpr manymore. and many, bacon, and Miley outofcandy, Cyruscrafted Snoopcosmetics andfeathers, Doggsculpt Here is fromher AmySedaris assembled six photo taking months. scale workssuchasa9’x12’recreation sculpture. Eachportrait cantakeupwa sees howMecier masterfullyelevates mu they capture their subjects. Bu A first glance, theseportraits ar is thefirstcollection of celebrities andartcollectorsaroundtheglobe. in music TVshows, andhangin videos, thehomesof andhave appeared astheyareoutrageous, as beautiful Mecier’stheir useofmaterials. sculpturalcelebrations are butalsoclever in that arenotonlyinstantly recognizable, toreveal insanelydetailedcelebrityportraits assembles items fromtherubbish bin, theseare the Colorful candies, computer f parts, 2018 JulyOn Sale: 17, April Contact: Whitney visit creati spirit, forits recognizable that’spublishing instantly andpop culture, acclaimed children’s titles. Chronicle Bo products booksandgift includesthat -

1458697499761.Pdf

THE ETHICAL A PRACTICAL GUIDE TO POLYAMORY, OPEN RELATIONSHIPS & OTHER ADVENTURES 2ND EDITION UPDATED & EXPANDED DOSSIE EASTON AND JANET W. HARDY CELESTIAL ARTS Berkeley Copyright © 1997, 2009 by Dossie Easton and Janet W. Hardy All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Celestial Arts, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. www.crownpublishing.com www.tenspeed.com Celestial Arts and the Celestial Arts colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc. Previous edition published as The Ethical Slut: A Guide to Infinite Sexual Possibilities, by Dossie Easton and Catherine A. Liszt (Greenery Press, 1997). LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Easton, Dossie. The ethical slut: a practical guide to polyamory, open relationships, and other adventures. - 2nd ed., updated & expanded I Dossie Easton and Janet W. Hardy. p. cm. Includes index. Summary: "A practical guide to practicing polyamory and open relationships in ways that are ethically and emotionally sustainable"-Provided by publisher. 1. Non-monogamous relationships-United States. 2. Free love-United States. 3. Sexual ethics-United States. 4. Sex-United States. I. Hardy, Janet W. II. Title. HQ980.5.U5E27 2009 306.84'230973-dc22 2008043651 ISBN 9781587613371 Printed in the United States of America Cover design by The Book Designers Interior design by Chris Hall, Ampersand Visual Communications 11 109876543 Second Edition Contents Acknowledgments vii PART ONE WELCOME 1. Who Is an Ethical Slut? 3 2. Myths and Realities 9 3. Our Beliefs 20 4. Slut Styles 27 5. Battling Sex Negativity 4I 6. Infinite Possibilities 46 PART TWO THE PRACTICE OF SLUTHOOD 7.