Temporal Landscapes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction//012 Origins and Definitions//022 Conventions

Introduction//012 ORIGINS AND DEFINITIONS//022 CONVENTIONS//036 DOES DOCUMENTARY EXIST?//050 PHOTOJOURNALISM AND DOCUMENTARY: FOR, AGAINST AND BEYOND//078 ACTIVE AND PASSIVE SPECTATORS//116 THE LIMITS OF THE VISIBLE//150 DOCUMENTARY FICTIONS//178 COMMITMENT//198 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES//228 Bibliography//230 INDEX//234 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS//239 The immediate instruments are two: the motionless camera and the printed word. The governing instrument – which is also one of the centres of the subject – is individual, anti-authoritative human consciousness. James Agee, with Walker Evans, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, 1941 ORIGINS AND DEFINITIONS ACTIVE AND PASSIVE SPECTATORS Walter Benjamin Thirteen Theses Against Snobs, Susan Sontag On Photography, 1977//118 1928//024 Martha Rosler in, around, and afterthoughts Elizabeth McCausland Documentary Photography, (on documentary photography), 1981//122 1939//025 Ariella Azoulay Citizenship Beyond Sovereignty: James Agee, with Walker Evans Let Us Now Praise Towards a Redefinition of Spectatorship, 2008//130 Famous Men, 1941//029 Judith Butler Torture and the Ethics of Photography, John Grierson Postwar Patterns, 1946//030 2009//135 Hito Steyerl A Language of Practice, 2008//145 CONVENTIONS Philip Jones Griffiths The Curse of Colour, 2000//038 THE LIMITS OF THE VISIBLE An-My Lê Interview with Art21, 2007//042 Georges Didi-Huberman Images in Spite of All: David Goldblatt Interview with Mark Haworth-Booth, Four Photographs from Auschwitz, 2003//152 2005//047 Harun Farocki Reality Would Have to Begin, 2004//155 Lisa F. Jackson Interview with Melissa Silverstein, DOES DOCUMENTARY EXIST? 2008//163 Carl Plantinga What a Documentary Is, After All, Lisa F. Jackson Interview with Ben Kharakh, 2008//165 2005//052 Ursula Biemann Black Sea Files, 2005//168 Jacques Rancière Naked Image, Ostensive Image, Marta Zarzycka Showing Sounds: Listening to War Metamorphic Image, 2003//063 Photographs, 2012//171 Trinh T. -

Lewis Baltz: Discovering Park City

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Fall 12-21-2016 Lewis Baltz: Discovering Park City Susan H. West CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/107 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Lewis Baltz: Discovering Park City by Susan H. West Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History, Hunter College The City University of New York 2016 Thesis Sponsor: December 7, 2016 Maria Antonella Pelizzari Date First Reader December 7, 2016 Michael Lobel Date Second Reader TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface iii List of Illustrations v Introduction 1 Chapter I Photographs of Park City, Utah (1978–1979) 9 Chapter II Lewis Baltz and California at Mid-Century 26 Chapter III The Seventies – Influences and The Prototype Works 36 Chapter IV American Nationalism and Westward Expansion 44 Chapter V Land Art and Environmentalism 53 Chapter VI New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-altered Landscape 62 Conclusion 69 Bibliography 70 Illustrations 73 ii Preface This research synthesizes interests in photography, land art, post-war cultural studies, and American history. In 2012, I enrolled in my first course at Hunter College: “Research Methods,” taught by William Agee, former Evelyn Kranes Kossak Professor of Art History. Agee was the first to encourage my interests, challenge my ideas, and instill confidence in my scholarship. -

Introduction Case Study: Photography Into Sculpture

INTROduCTION Case Study: Photography into Sculpture In 1979, Peter Bunnell, the David Hunter McAlpin Professor of the History of Pho- tography and Modern Art at Princeton University, gave a lecture at Tucson’s Center for Creative Photography (CCP) titled “The Will to Style: Observations on Aspects of Contemporary Photography.”1 James Enyeart, the CCP’s director, introduced Bunnell and listed his many accomplishments, including his tenure as a curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art (1966– 72), noting in particular his 1970 exhibition there Photography into Sculpture. Enyeart called it “one of the preeminent exhibitions of the decade.” But at the end of the talk, the focus of which was not photo sculpture or other experimental forms, but straight photography, Bunnell offered his own assessment of the exhibition, which was decidedly less positive. In his complex and carefully argued lecture, Bunnell defended Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander, whose work had recently come under attack by Janet Malcolm in her New Yorker essay “Diana and Nikon” for making presumably style-less photographs that were “indistinguishable” from snapshots and just as unsophisticated and offhand as those made by amateur photographers.2 Bunnell argued that Winogrand’s and Fried- lander’s photographs were absolutely not snapshots, and demonstrated the point by com- paring them to actual snapshots taken by random amateurs who had participated in Ken Ohara’s Snapshot Project.3 Citing the Russian formalist Victor Shklovsky and the Marxist cultural critic Fredric Jameson, Bunnell asserted that “defamiliarization” was one of the primary strategies deployed by Winogrand and Friedlander, noting that “in their hands, defamiliarization became an attack . -

Whitechapel Gallery Name an Exhibition

Whitechapel Gallery Name an Exhibition To name an exhibition contact Development Manager Sue Evans T: 0207 522 7860 E: [email protected] 1901 Modern Pictures by Living Artists: Pre-Raphaelites and Older English Masters – Burne- Jones, Constable, Hogarth, Raeburn, Rubens – Dominic Palfreyman Chinese Life and Art Scottish Artists – Bone, Landseer, Mactaggart, Muirhead, Whistler 1902 Cornish School- Forbes, Stokes Japanese Exhibition Children's Work: Tower Hamlets Schools 1903 Artists in the British Isles at the Beginning of the Century – Fry, Legros, Tonks, Watts Poster Exhibition: British, European, Chinese and Japanese Shipping 1904 Scholars' Work from Board Schools in Bethnal Green, Stepney and Poplar Dutch Art – Hals, de Koninck, Metsu, Rembrandt, van Ruisdael, Amateurs and Arts Students Indian Empire 1905 LCC Children's Work from Board Schools in Bethnal Green, Stepney, Poplar British Art 50 Years Ago – Hunt, Millais, Rossetti, Ruskin, Turner Photography – Chesterton, Pike, Reid, Selfe, Wastell 1906 Georgian England Country in Town Jewish Art and Antiquities 1907 Old Masters: XVII and XVIII Century French and Contemporary British Painting and Sculpture – Boucher, Le Brun, Chardin, Claude, David, Grenze, Poussin Country in Town Animals in Art 1908 Contemporary British Artists: Collection of Copies of Masterpieces – Gainsborough, Holroyd, Latour, Stevens, Teniers Country in Town Muhammaden Art and Life (in Turkey, Persia, Egypt, Morocco and India) 1909 Stepney Children’s Pageant Tuberculosis Flower Paintings and Old Rare -

Aspects of Portraiture: Photographs from the Wadsworth Atheneum July 11 – Nov

Aspects of Portraiture: Photographs from the Wadsworth Atheneum July 11 – Nov. 15, 2015 Exhibition Checklist 1. Kota Ezawa Ansel Adams, 2005 Transparency, lightbox 30 x 20 inches Alexander A. Goldfarb Contemporary Art Acquisition Fund, 2006.25.1 TRADITIONAL PORTRAITS 2. Richard Avedon Escudero, ca. 1950 Photograph 13 x 11 inches Gift of Janet and Simeon Braquin, 1990.47 3. Dawoud Bey Lakeisha, Jackie and Crystal, 1996 Polacolor ER prints, eight panels 60 3/4 x 91 1/2 inches overall, framed Gift exchange through funds from The Larsen Fund for Photography, 1997.6.1a-h 4. Ellen Carey Andrea (Green), 1995 Polaroid 24 x 20 inches Purchased through the Nancy and Robinson Grover Fund for Contemporary Art, 1996.4.8 5. Timothy Greenfield-Sanders Kara Walker, 2008 Photograph 40 x 30 inches, sheet Gift of Isca Greenfield-Sanders & Sebastian Blanck, 2010.9.1 Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art Page 1 of 8 Exhibition Checklist, Aspects of Portraiture: Photographs from the Wadsworth Atheneum 6-10-15-ay 6. Pedro Guerrero (Portrait of Calder), 1975 Photograph 9 15/16 x 7 15/16 inches, paper Gift of Pedro E. Guerrero and Dixie Legler, 2006.28.20 7. McDermott & McGough The Annointed 1898, 1991 Palladium print 16 7/8 x 11 7/8 inches, paper Given by Robinson and Nancy Grover to honor Cecil Adams, Head of Museum Design, and Alan Barton, Director of Facilities, in recognition of their years of service to the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, 2010.24.2.2 8. Arthur Mones George Segal, 1983 Gelatin silver print 14 x 11 inches Gift of the photographer, 1995.8.1.8 9. -

To What Extent Did the New Topographic Movement Reflect Changing Attitudes Towards Landscape Photography?

Laura Aldington To what extent did the new topographic movement reflect changing attitudes towards landscape photography? “Landscape photographs can offer us, I think, three truths- geography, if taken on its own, is sometimes boring, autobiography is frequently trivial, and metaphor can be dubious. But taken together... the three kinds of information strengthen each other and reinforce what we all work to keep in tact- an affection for life.”1 This essay will explore the genre of landscape photography, in particular focusing on the New Topographic movement. The aim of the essay is to evaluate and asses to what extent the New Topographic movement reflects the changing attitudes towards landscape photography. Within this it will therefore come across several other important questions, looking into what is perceived as a landscape, whether aspects of landscape photography may have changed and exploring to what extent the new topographic movement had a role to play in this, if at all. As the aim is to look at changing attitudes towards landscape photography, it may also be considered beneficial when answering the question, to explore political and social factors which may have an influence on landscape photography, and the changing ways people perceive it as a genre. Defining 'landscape' tends to be controversial. There is a difference between 'land' and 'landscape'. In principle the land is a natural phenomenon, although land in modern times (particularly in the developing and developed world) tends to be subject to human intervention 2. This can be seen through acts such as the industrial revolution, industrialisation, urban sprawl and deforestation. -

Reframing the New Topographics Free

FREE REFRAMING THE NEW TOPOGRAPHICS PDF Gregory Foster-rice,John Rohrbach | 264 pages | 12 Apr 2013 | Columbia College Chicago | 9781935195405 | English | Chicago, United States New topographics – Art Term | Tate Organized at the George Eastman Museum in Rochester, New York, the show featured ten photographers who examined the American landscape in a new way. They furthermore rendered these banal subjects with a style that suggested cool detachment. While visiting the exhibition, people voiced a range of reactions:. Preserved within these comments are the expectations these visitors held about the American landscape and its representation. Given that people largely found the work off-putting and difficult to interpret, how did New Topographics come to be regarded as one of the most important photography exhibitions of the 20 th century? On the one hand, New Topographics represented a radical shift by redefining the subject of landscape photography as the built as opposed to the natural environment. To comprehend the significance of this, it helps to consider the type of imagery that previously dominated the genre in the United States. Beginning in the s, Ansel Adams cultivated an approach Reframing the New Topographics landscape photography that posited nature as separate from human presence. Consistent with earlier American landscape painting Reframing the New Topographics, Adams photographed scenery in a manner intended to provoke feelings of awe and pleasure in the viewer. He used vantage points that emphasized the towering scale of mountain peaks, and embraced a wide tonal range from black to white to record texture and dramatic effects of light and weather. His heroic, timeless photographs contributed to the cause Reframing the New Topographics conservationism—the environmental approach that seeks to preserve exceptional landscapes and protect them from human intervention. -

Landscape: New Topographics

Landscape New Topographics Landscape The Land is America “The land is to American art what mythology, religion and belief were to European art. From nearly the beginning of American art, painters made roman?c, idyllic pain?ngs of the land. Those portrayals con?nued for almost two centuries. They went up the Hudson River, west to Niagara Falls, across the great rivers of the heartland, over the West and her mountains un?l finally the land was so used-up by Americans (and ar?sts) that full-field abstrac?on was the only way leH. ” Tyler Green hKp://blogs.ar?nfo.com/modernartnotes/2010/01/the-new-new-topographics-at-la/ RALPH EARL American, 1751-1801 Looking East from Denny Hill, 1800 Alexandre Clausel (French, 1802–1884) Landscape near Troyes, ca. 1855 Daguerreotype; 10.5 x 14.6 cm (4 1/8 x 5 3/4 in.) George Eastman House, Rochester Victor Regnault (1810-78), View of the Seine at Sèvres, circa 1852, salt print, 31.4 by 42.8 cm Louis-Auguste Bisson (1814-1876) and Auguste-Rosalie Bisson (1826-1900). Mont Blanc, vu du jardin", 1858. Album Haute-Savoie. Le mont Blanc et ses glaciers. Souvenir du voyage de LL. MM. l'empereur et l'impératrice, par MM. Bisson frères photographes de Sa Majesté l'empereur. Afong Lai, Entrance to the Bankers' Glen, view looking down Yuen-foo River, China 1870. “A Harvest of Death.” This image was taken by Timothy H. O’Sullivan for Alexander Gardner circa july 5-6, 1863. hKp://www.geKysburgdaily.com/?p=13862 Ansel Adams Early Landscape Photography in America • Spirit Father of American Landscape • Nature before photography •Conservaonist •Zone System “The negave is comparable to the composer’s score and the print to its performance.” jack Dykinga • Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist • Purpose of preservaon and protec?on • 4x5 digital camera • Internaonal League of Conservaon Photographers (www.ilcp.com), an organizaon of photographers working to protect threatened wild lands along the U.S.-Mexico border. -

Syllabus Is from a Previous Iteration of This Course

***This syllabus is from a previous iteration of this course. This course will be taught in Spring 2016 as an immersion. Use this syllabus only as a very general outline of what the course will entail.*** Arts 626 Landscape Photography/Cultural Geography Marion Belanger Tuesday 6:30 PM - 9:00 PM Objectives This seminar attempts to do several things at once: we will develop a visual astuteness by which we can talk about pictures, and we will further our awareness of photographers who address issues of landscape; we explore contemporary dialogues regarding land, culture and ethics, and we develop our own photographic competence. Required Texts Robert Adams, Along Some Rivers Publisher: Aperture ISBN: 1-59711-004-3 John Brinckerhoff Jackson, Discovering the Vernacular Landscape Publisher: Yale University Press ISBN: 0300035810 A reading packet will be available for purchase at the first class. Approximate cost: $20 Additional material will be on reserve in the Art Library. The three main components of this course are: Weekly Assignments Students will be expected to produce photographic responses to class issues pertaining to “landscape”. I am flexible in terms of film and format, as long as there a camera with manual controls is used. Each person will present his or her images to the class for critique. Weekly readings will inform our visual investigations and provide a context for dialogue. Papers One response paper to a gallery exhibition, of 3-4 pages. Report on a Contemporary Landscape Photographer Students will present on the work of a landscape photographer selected from a provided list. Presentations should be approximately 15 minutes and include visuals. -

Geography Topography and Cultural Landscape

Geography Topography and Cultural Landscape Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Fine Arts in Visual Art Program at Vermont College of Fine Arts Submitted By David Kutz July 18, 2016 _____________________________________________________ Faculty Co-Chair Contents Page Acknowledgements 1 Introduction 2-4 Praxis 5 More On Maps 6-8 Praxis 9-10 On Travel 11-14 Praxis 15 A Brief On Cultural Landscape As Art 16-22 Praxis 23 New Topographics - New Landscapes 24-27 Praxis 28 After New Topographics 29-30 Praxis 31 Conclusion 32 Bibliography 33-38 Footnotes 39-40 Acknowledgements It is difficult to acknowledge properly all of my intellectual debts. I owe so much to so many. All of this would not be possible without the ever present support and insight provided by my much loved wife, Ruth Dresdner. Our brilliant children, Gideon and Maya, are the joy of my life and a constant inspiration. If you asked Cornell Capa if he thought photography was an art, he would first look at you quizzically and then in his boisterous Hungarian manner he would howl. That was the end of that question. Cornell, who I loved dearly, identified much more closely with Louis Hine, the great social-activist photographer, who famously said, "I wanted to show the things that had to be corrected. I wanted to show the things that had to be appreciated". Hine also said, "In the last analysis, good photography is a question of art". 1 Cornell once told me that the experiences I had while working for him at the International Center of Photography in the 1970s would be important for the rest of my life. -

Download-To-Own from the and Educational Resources

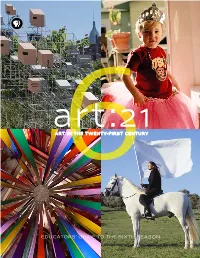

art:21 educators’ guide to the sixth season Art21 Staff Executive Director/ Series Executive Producer, Director, Curator: Susan Sollins Managing Director/ Series Producer: Eve Moros Ortega Associate Curator: Wesley Miller Director, Art21 Educators: Jessica Hamlin Senior Education Advisor: Joe Fusaro Manager of Digital Media and Strategy: Jonathan Munar Director of Development: Diane Vivona Development Associate: KC Forcier Development Assistant: Heather Reyes Director of Production: Nick Ravich Production Coordinator: Ian Forster Art21 Series Contributors Consulting Directors: Charles Atlas, Catherine Tatge Series Editors: Lizzie Donahue, Mark Sutton Companion Book & Educators’ Guide Design: Russell Hassell Companion Book & Educators’ Guide Editor: Marybeth Sollins Art21 Education and Public Programs Advisory Council Christin Baker, YMCA of the USA; Laura Beiles, Museum of Modern Art; Susan Chun, Cultural Heritage Consulting; William Crow, Metropolitan Museum of Art; Dipti Desai, New York University; Rosanna Flouty, Educational Consultant; Tyler Green, Modern Art Notes Media; Olivia Gude, University of Illinois at Chicago; Jeanne Hoel, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; Eliza Licht, POV; Nate Morgan, Hillside School; Frank Smigiel, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Mary Ann Stankiewicz, Penn State University. Funders Lead Sponsorship of Season Six Education programs and materials has been provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. Major underwriting for Season Six of Art in the Twenty-First Century and its accompanying education -

Alfredo Jaar

ALFREDO JAAR Born 1956, Santiago, Chile Lives and works in New York, New York SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 The Hasselblad Foundation International Award in Photography Exhibition, Gothenburg, Sweden 11th Hiroshima Art Prize Award Ceremony and Commemorative Exhibition, Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, Japan Alfredo Jaar: The Rwanda Project, Zeits Museum of Contemporary Art Africa, Cape Town, South Africa 2019 Alfredo Jaar: Men Who Cannot Cry, Goodman Gallery, London, England The Garden of Good and Evil, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, West Bretton, England The Divine Comedy, Museum of Old and New Art, Hobart, Tasmania Alfredo Jaar: 1973, Galerie Hubert Winter, Vienna, Australia Alfredo Jaar: Lament of the Images, SCAI THE BATHHOUSE, Tokyo, Japan Alfredo Jaar: Lament of the Images, Synagoge Stommeln, Pulheim, Germany Alfredo Jaar: The Sound of Wind, Kenji Taki Gallery, Tokyo, Japan The Seven Lamps of the Art Museum, Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, Hiroshima City, Japan Shadows, Nederlands Fotomuseum, Rotterdam, The Netherlands 2018 Alfredo Jaar: Men Who Cannot Cry, Goodman Gallery, Cape Town Alfredo Jaar: Lament of Images, Galleria Lia Rumma, Milan 2017 Alfredo Jaar: The Garden of Good and Evil, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, Wakefield, United Kingdom Alfredo Jaar: The Politics of Images, Galeria Massangana, Joaquim Nabuco Foundation, Recife, Brazil Shadows, Lisboa Capital Iberó-Americana da Cultura 2017, Carpintarias de São Lázaro, Portugal Shadows, Galerie Thomas Schulte, Berlin, Germany 2016 Alfredo Jaar: The Politics of Images, Trish