Benjamin Tarr Thesis (PDF 1MB)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ATHLETE SPOTLIGHT. MADISON HUGHES - MEN’S RUGBY the U.S

THE UNITED STATES OLYMPIC COMMITTEE ATHLETE SPOTLIGHT. MADISON HUGHES - MEN’S RUGBY The U.S. Rugby Sevens Men’s National Team had success during February as did Team Captain Madison Hughes. The Eagles traveled to the Wellington Sevens the first weekend in February and then went directly to the USA Sevens tournament as part of the HSBC Sevens World Series. Hughes scored a total of two tries and 11 conversions at the Wellington tournament. During the USA Sevens tournament, he scored three tries and six conversions and was named to the tournament’s Dream Team. This was Hughes first time being selected to a Dream Team. Hughes’ performance throughout the season has him leading the U.S team in tackles and points scored and he also is in the top ten worldwide for both categories at the halfway point of the 2014-2015 season. A native of London, England, Hughes was introduced to rugby at the age of seven. He excelled in the sport and eventually began playing for the Dartmouth rugby team upon starting college there. Hughes Madison Hughes runs through the South African was a member of both the Dartmouth 15s and 7s rugby teams. As a defense at the Las Vegas Sevens tournament. junior, Hughes was named captain of the Dartmouth rugby team, the Photo Credit: Michael Lee - KLC fotos youngest person in the school’s history to be named rugby captain. Hughes began his career with USA Rugby as a member of the AIG Men’s Junior All-American team. He helped the team win the 2012 IRB Junior World Rugby Trophy. -

(2019) 1 WSU Five-Year Graduate Program Review Self-Study Cover Page Department/Program

WSU Five-Year Graduate Program Review Self-Study Cover Page Department/Program: Master of Science in Athletic Training Semester Submitted: Fall 2019 Self-Study Team Chair: Matthew Donahue Self-Study Team Members: Valerie Herzog, Conrad Gabler, Hannah Stedge, Alysia Cohen Contact Information: Matthew Donahue PhD LAT ATC Program Director, Master of Science in Athletic Training Associate Professor Weber State University Department of Athletic Training 3992 Central Campus Drive, Dept 3504 Ogden, UT 84408-3504 Information Regarding Current Review Team Members: WSU Faculty member outside the program within DHCP: Kenton J. Cummins, MHA, MLS(ASCP)CM Medical Laboratory Sciences University Pre-PA Advisor Weber State University Work: (801)626-6718 [email protected] Sally Cantwell, PhD, RN Associate Chair, Annie Taylor Dee School of Nursing Associate Professor Weber State University Work: (801) 626-7858 [email protected] Faculty member outside WSU: Dani Moffit PhD LAT ATC Program Director, Master of Science in Athletic Training Sport Science & Physical Education 921 South 8th Ave. Stop 8105 Pocatello, ID 83209 [email protected] WSU Graduate Program Review Form (2019) 1 A. Brief Introductory Statement The Master of Science in Athletic Training (MSAT) program at Weber State University is accredited by the Commission on Accreditation of Athletic Training Education (CAATE). This accreditation is awarded following the submission of a detailed self- study document as well as an on-campus site visit. This program received its initial accreditation with zero citations in March 2010, and was reaccredited in November 2014. In almost every state, in order to work as an Athletic Trainer, one must graduate from an accredited AT program and pass the Board of Certification (BOC) exam for Athletic Trainers. -

Atlanta Braves Clippings Thursday, September 10, 2020 Braves.Com

Atlanta Braves Clippings Thursday, September 10, 2020 Braves.com Braves set NL standard with 29-run outburst Atlanta breaks Modern Era record in National League (since 1900) By Mark Bowman ATLANTA -- Adam Duvall produced his second three-homer game within an eight-day span to help the Braves roll to a record-setting 29-9 win over the Marlins on Wednesday night at Truist Park. Duvall became the first player to record two three-homer games while wearing a Braves uniform, and his efforts helped Atlanta set a National League record for runs in a game in the modern era (since 1900). “That was pretty amazing to be a part of,” Braves first baseman Freddie Freeman said. “I’ve never seen an offense click like that.” The Braves fell just one run short of tying the modern record for runs scored in a game, set when the Rangers defeated the Orioles, 30-3, in the first game of a doubleheader on Aug. 22, 2007, at Camden Yards. Dating back to 1900, no NL club had scored more than 28 runs in a game. The Braves’ franchise record was 23, a mark tallied during the second game of a doubleheader against the Cubs on Sept. 2, 1957. Ronald Acuña Jr. contributed to his three-hit night with a three-run home run to cap a six-run fifth. But it was his bases-loaded double in the sixth inning that gave the Braves a new franchise record for runs in a single game, opening a 25-8 lead. According to the Elias Sports Bureau, Atlanta became the first MLB team to score at least 22 runs through the first five innings since the Blue Jays (24 runs) in a win over the Orioles on June 26, 1978. -

Match Summary

MATCH SUMMARY TEAMS Australia vs Wales VENUE Tokyo Stadium DATE 29 September 2019 09:45 COMPETITION Rugby World Cup 2019 FINAL SCORE 25 - 29 HALFTIME SCORE 8 - 23 TRIES 3 - 2 PLAYER OF THE MATCH Gareth Davies (Wales) SCORING SUMMARY Australia Wales PLAYER T C P DG PLAYER T C P DG Adam Ashley-cooper (J #14) 1 0 0 0 Dan Biggar (J #10) 0 2 0 1 Bernard Foley (J #10) 0 0 1 0 Hadleigh Parkes (J #12) 1 0 0 0 Dane Haylett-petty (J #15) 1 0 0 0 Rhys Patchell (J #22) 0 0 3 1 Matt To'omua (J #22) 0 2 1 0 Gareth Davies (J #9) 1 0 0 0 Michael Hooper (J #7) 1 0 0 0 LINE-UP Australia Wales 1 Scott Sio (J #1) 1 Wyn Jones (J #1) 2 Tolu Latu (J #2) 2 Ken Owens (J #2) 3 Allan Alaalatoa (J #3) 3 Tom Francis (J #3) 4 Izack Rodda (J #4) 4 Jake Ball (J #4) 5 Rory Arnold (J #5) 5 Alun Wyn Jones (J #5) 6 David Pocock (J #6) 6 Aaron Wainwright (J #6) 7 Michael Hooper (J #7) 7 Justin Tipuric (J #7) 8 Isi Naisarani (J #8) 8 Josh Navidi (J #8) 9 Will Genia (J #9) 9 Gareth Davies (J #9) 10 Bernard Foley (J #10) 10 Dan Biggar (J #10) 11 Marika Koroibete (J #11) 11 Josh Adams (J #11) 12 Samu Kerevi (J #12) 12 Hadleigh Parkes (J #12) 13 James O'connor (J #13) 13 Jon Davies (J #13) 14 Adam Ashley-cooper (J #14) 14 George North (J #14) 15 Dane Haylett-petty (J #15) 15 Liam Williams (J #15) RESERVES Australia Wales 16 Jordan Uelese (J #16) 16 Elliot Dee (J #16) 17 James Slipper (J #17) 17 Nicky Smith (J #17) 18 Sekope Kepu (J #18) 18 Dillon Lewis (J #18) 19 Adam Coleman (J #19) 19 Aaron Shingler (J #19) 20 Lukhan Salakaia-loto (J #20) 20 Ross Moriarty (J #20) 21 Nic White -

P12 Layout 1

SUNDAY, AUGUST 20, 2017 SPORTS Pritchett has quickest run 2018 Vuelta to Kyle Busch wins at in NHRA history at 3.640s begin in Malaga Bristol for 19th time BRAINERD: Leah Pritchett had the quickest run in NHRA history with NIMES: Next year’s Vuelta a Espana will start with a time trial in BRISTOL: Kyle Busch continued his domination at Bristol Motor Speedway 3.640-second pass at 330.63 mph Friday night at Brainerd International Malaga, race organisers announced yesterday. “The (2018) Vuelta will with a victory Friday night in the Xfinity Series race. The win was the 19th Speedway in Lucas Oil NHRA Nationals qualifying. She broke her own Top start August 25 in Malaga,” race director Javier Guillen told reporters in national series victory at Bristol for Busch, who also won the Truck Series Fuel record of 3.658 set in Arizona in February. “We’ve looked forward to the French city of Nimes. The 2017 edition begins later Saturday in race Wednesday night. And just like that win, Busch had to overcome a this night session for a long time,” Pritchett said. “Knowing that Nimes, just the third time the race has started outside of Spain. It set speeding penalty on pit road to get to victory lane. “Just a great car,” Busch Brainerd, this track, this surface, the conditions and what NHRA off from the Portuguese capital Lisbon in 1997 and from Assen in the said about his Joe Gibbs Racing Toyota. Busch won the first stage of the race is able to do to it, lays down the ground work for us to pull out Netherlands in 2009. -

Economic Impact Report on Global Rugby

EMBARGOED UNTIL 9am GMT, 5 April 2011 ECONOMIC IMPACT REPORT ON GLOBAL RUGBY PART III: STRATEGIC AND EMERGING MARKETS Commissioned by MasterCard Worldwide Researched and prepared by the Centre for the International Business of Sport Coventry University Dr Simon Chadwick Professor of Sport Business Strategy and Marketing Dr. Anna Semens Research Fellow Dr. Eric C. Schwarz, Department of Sport Business and International Tourism School of Business Saint Leo University Dan Zhang, Sport Business Consultant March 2010 1 Economic Impact Report on Global Rugby, Part III: Strategic and Emerging Markets EMBARGOED UNTIL 9am GMT, 5 April 2011 Highlights More than 5 million people play rugby in over 117 countries. Participation in rugby worldwide has increased 19% since the last Rugby World Cup in 2007. Participation figures are highest in Europe, but there are significant numbers of players elsewhere, with increasing numbers in emerging markets. Since 2007 participation has grown by 33% in Africa, 22% in South America and 18% in Asia and North America. In terms of participation, Japan, Sri Lanka and Argentina now feature in the top ten countries, which bodes well as there is a strong, positive correlation between participation and performance. These unprecedented levels of growth can be attributed to three main factors: o Developments in non-traditional game formats, particularly Sevens Rugby’s inclusion in the Olympic program from 2016. o Event hosting strategies often with linked legacy programs. o IRB programs and investment. £153 million (USD245.6 million) is being invested from 2009 to 2012, an increase of 20% over the previous funding cycle. Introduction Following Six Nations and Tri Nations reports, MasterCard commissioned the Centre for the International Business of Sport (CIBS) to look at rugby in emerging markets. -

Match Summary

MATCH SUMMARY TEAMS Australia vs Fiji VENUE Sapporo Dome DATE 21 September 2019 06:45 COMPETITION Rugby World Cup 2019 FINAL SCORE 39 - 21 HALFTIME SCORE 12 - 14 TRIES 6 - 2 PLAYER OF THE MATCH SCORING SUMMARY Australia Fiji PLAYER T C P DG PLAYER T C P DG Michael Hooper (J #7) 1 0 0 0 Ben Volavola (J #10) 0 1 3 0 Christian Lealiifano (J #10) 0 1 0 0 Peceli Yato (J #7) 1 0 0 0 Reece Hodge (J #14) 1 0 1 0 Waisea Nayacalevu (J #13) 1 0 0 0 Tolu Latu (J #2) 2 0 0 0 Samu Kerevi (J #12) 1 0 0 0 Matt To'omua (J #22) 0 2 0 0 Marika Koroibete (J #11) 1 0 0 0 LINE-UP Australia Fiji 1 Scott Sio (J #1) 1 Campese Ma’afu (J #1) 2 Tolu Latu (J #2) 2 Samuel Matavesi (J #2) 3 Allan Alaalatoa (J #3) 3 Peni Ravai (J #3) 4 Izack Rodda (J #4) 4 Tevita Cavubati (J #4) 5 Rory Arnold (J #5) 5 Leone Nakarawa (J #5) 6 David Pocock (J #6) 6 Dominiko Waqaniburotu (J #6) 7 Michael Hooper (J #7) 7 Peceli Yato (J #7) 8 Isi Naisarani (J #8) 8 Viliame Sevaka Mata (dnu) (J #8) 9 Nic White (J #9) 9 Frank Lomani (J #9) 10 Christian Lealiifano (J #10) 10 Ben Volavola (J #10) 11 Marika Koroibete (J #11) 11 Semi Radradra (J #11) 12 Samu Kerevi (J #12) 12 Levani Botia (J #12) 13 James O'connor (J #13) 13 Waisea Nayacalevu (J #13) 14 Reece Hodge (J #14) 14 Josua Tuisova (J #14) 15 Kurtley Beale (J #15) 15 Kini Murimurivalu (J #15) RESERVES Australia Fiji 16 Jordan Uelese (J #16) 16 Ratu Vere Vugakoto (J #16) 17 James Slipper (J #17) 17 Eroni Mawi (J #17) 18 Sekope Kepu (J #18) 18 Manasa Saulo (J #18) 19 Adam Coleman (J #19) 19 Tevita Ratuva (J #19) 20 Lukhan Salakaia-loto (J -

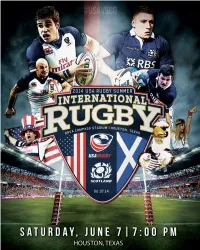

Usavsco-Official-Program.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the President 2 United States Roster 6-7 Scotland Roster 9-10 ‘Til the Motor Stops 13 An American Sporting Experience 22 Thank you to our sponsors 27 LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT It gives me great pleasure to welcome you to BBVA Compass Stadium in Houston for tonight’s international game between the USA Eagles and Scotland. Once again we are expecting a warm Texas welcome for our visitors from Scotland and a superb day of rugby for everyone involved. Since the Eagles were last in Houston, they have been developing as a team, recording an impressive November Tour in 2013 where they ran the New Zealand Maori All Blacks close in Philadelphia before recording important wins against Georgia and Russia abroad. They then faced World Cup qualifiers against Uruguay and we were all delighted for Coach Mike Tolkin and his team when they qualified for the 2015 Rugby World Cup. The significance of tonight’s game is that in just over 12 months time, Scotland and the Eagles will be meeting again in the 2015 Rugby World Cup pool, a chance tonight perhaps for both teams to start their preparations for what will be a very important pool game in Leeds, England on September 27, 2015. Our visitors from Scotland are currently ranked 10 in the World rankings, they had a disappointing RBS Six Nations tournament this year, but with a new coaching team led by former Clermont coach Verne Cotter, the Eagles know they are in for a severe test of their credentials tonight. -

Much-Changed Japan Seeks Shock No 2 at World

WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 23, 2015 SPORTS Has the ‘scrum doctor’ cured Australia woes? CARDIFF: It’s a tag that’s been thrown at as a scrum consultant for the New South Australia’s rugby team for years. Silky Wales Waratahs in Super Rugby. behind the scrum. Brittle in it. Nearly a year “He’s really passionate about scrums, into the tenure of coach Michael Cheika, and it’s good to have someone who has a the Wallabies are hoping those days are real identity of how he wants to shape the over heading into their first match of the scrum and how he wants the scrum to Rugby World Cup. move forward,” Hooper said. “He’s a great Cheika made improving Australia’s personality, a new face, a new accent in the scrummaging one of his priorities after group. He’s a great addition to the team.” replacing Ewen McKenzie in October. He England and Wales are expected to give saw the Australian eight get pushed Australia most problems in the scrum in around against England - yet again - in Pool A of the World Cup but the pack of the their November international last year, and Wallabies’ opening opponent, Fiji at the acknowledged his players’ technique and Millennium Stadium in Cardiff today, strategy needed to change. “Perhaps we shouldn’t be underestimated. are too honest,” he said. Fiji shoved back England’s vaunted To rectify the problem, Cheika changed scrum at one point in the tournament’s personnel. Benn Robinson and Ben opening game last Friday, and wheeled Alexander, Australia’s two most experi- another on England’s own feed five meters enced props, were ditched ahead of the from its tryline, leading to a try from Fiji World Cup, and younger players such as winger Nemani Nadolo. -

2020 Gala Program

2.22.20 CRISTO REY Benefitting Jim kim & scott Presenting Sponsors Childs kingsfield Serving communities. Changing lives. What matters to you matters to us. At EY, we’re proud to support Cristo Rey Jesuit High School. It’s one of the ways we’re helping to make our community a better place to work and live. A better and brighter future starts with all of us. Visit ey.com © 2020 Ernst & Young LLP. All Rights Reserved. EDNone Reserved. All Rights LLP. & Young © 2020 Ernst Welcome! Welcome to the second Rey of Hope Gala – a celebration of our most generous donors and our fearless leader, Bill Garrett. Tonight is also a celebration of the 525 students we have the honor to serve every day. These extraordinary young people make us proud as they travel the city to work in their corporate jobs, and as their remarkable achievements in the classroom. Their youth brings energy, creativity and a fresh perspective to our 132 corporate jobs partners. This year’s senior class will graduate in May, joining the 237 alumni who have gone before them, and 100% of them have been accepted into college. Our graduates attend some of the country’s most prestigious colleges, and this year we have our first student heading to an Ivy League college in the fall. It is humbling to think of how far this school has come in just six years. It is safe to say that all that has been accomplished would not have been possible without the leadership of Bill Garrett and the support of everyone here tonight. -

Dossier Rugby US Emilie Dudon

DOSSIER XXXXXXXXX TEXTESMADE : XXXXXX IN USA Voyage au cœur de la Major League, élite semi-profession- nelle du rugby américain qui rassemble aujourd’hui sept équipes dont une, basée à Austin, est entraînée par Alain Hyardet. Notre sport arrivera-t-il à se faire une place dans un pays qui peut devenir un nouveau lieu de développement ? REPORTAGE À HOUSTON D’ÉMILIE DUDON PHOTOS NORMA SALINAS, DAVE SNOOK ET ICONSPORT Midi Olympique Magazine 24 Midi Olympique Magazine 25 DOSSIER analyse UN NOUVEAU MONDE Le nouveau championnat professionnel américain, la Major League Rugby, qui a débuté fin avril et se terminera début juillet, bat son plein. Cette nouvelle compétition n’en est qu’à ses balbutiements mais ambi- tionne, d’ici dix ou quinze ans, de devenir l’une des meilleures de la planète rugby. En attendant, tout est à construire. TEXTE : ÉMILIE DUDON om-pom girls en jupettes, hymne na- complètement différente. Et les diri- tional chanté la main sur le cœur, pro- geants de la MLR veulent mettre toutes duits dérivés en pagaille et feux d’artifice les chances de leur côté pour réussir là à la fin de certains matchs… Aux États- où le Pro Rugby avait échoué il y a deux Unis, le sport professionnel est toujours ans. Lancé avec cinq équipes en 2016, le un show et le rugby n’échappe pas à la premier championnat professionnel Avant chaque rencontre, place à l’hymne américain. Moment d’émotion pour Todd Clever (cheveux longs), règle. Le niveau de jeu, qui est à peu américain n’avait pas survécu plus d’une ancien capitaine de l’équipe des États-Unis, et ses coéquipiers d’Austin. -

City Council Preview: April 22, 2019

TONIGHT Showers. Low of 51. Search for The Westfield News The WestfieldNews “LSearchIFE forIS The MADE Westfield UP News OF DESIRES Westfield350.com The WestfieldNews THAT SEEM BIG AND VITAL ONE Serving Westfield, Southwick, and surrounding Hilltowns “TIME ISMINUTE THE ONLY, AND LITTLE WEATHER CRITICAND ABSURD WITHOUT THE NEXT. TONIGHT I GUESS WEAMBITION GET WHAT.” ’S BEST Partly Cloudy. FORJOHN SearchSTEINBECK US IN for THEThe Westfield END.” News Westfield350.comWestfield350.orgLow of 55. Thewww.thewestfieldnews.com WestfieldNews — ALICE CALDWELL RICE Serving Westfield, Southwick, and surrounding Hilltowns “TIME IS THE ONLY WEATHERVOL. 86 NO. 151 TUESDAY, JUNE 27, 2017 75 centsCRITIC WITHOUT VOL.88TONIGHT NO. 91 SATURDAY, APRIL 20, 2019 75AMBITION Cents .” Partly Cloudy. JOHN STEINBECK Low of 55. www.thewestfieldnews.com WaterVOL. 86 NO. 151 TUESDAY, JUNE 27, 2017 City Council 75 cents treatment Preview: plant April 22, 2019 progressing By AMY PORTER Correspondent By DAVID BILLIPS WESTFIELD – The City Council Director of Public Works will meet this Monday evening, for the City of Westfield April 22, after rescheduling from With new proposed regulations April 18 due to school vacation coming out from the Massachusetts week with a packed agenda. The Department of Environmental meeting will open and immediately Protection (MassDEP) Bureau of Westfield High vs. Northampton go into executive session to discuss Waste Site Cleanup this week, the strategy with respect to litigation Department of Public Works – Water Westfield’s Emma LaPoint (33) tries to tag one at Friday’s game against concerning an eminent domain, Division is pleased to announce that Northampton High. See additional photos, story in today’s Sports Section.