Becoming: from Capture to Recovery’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southern & Hills Local Government

HDS Australia Civil Engineers and Project Managers Southern & Hills Local Government Association 2020 TRANSPORT PLAN – 2015 UPDATE Adelaide Final Report Melbourne Hong Kong HDS Australia Pty Ltd 277 Magill Road Trinity Gardens SA 5068 telephone +61 8 8333 3760 facsimile +61 8 8333 3079 email [email protected] www.hdsaustralia.com.au December 2016 Safe and Sustainable Road Transport Planning Solutions Southern & Hills Local Government Association HDS Australia Pty Ltd Key Regional Transport Infrastructure Initiatives Freight Development of the South Coast Freight Corridor as a primary cross regional gazetted 26m B-Double GML route (ultimately upgraded to a PBS Level 2A route) running from Cape Jervis, via Victor Harbor and Strathalbyn, to the South East Freeway Interchange at Callington, with a branch to Mount Barker. Development of the Southern Vales Wine Freight Corridor as a secondary cross regional gazetted 26m B-Double GML route running from McLaren Vale to the South East Freeway Interchange at Mount Barker. Development of the Kangaroo Island Freight Corridor as a secondary cross regional gazetted 23m B-Double GML route (upgraded to 26m B- Double when the Sealink Ferry capability permits) running from Gosse to Penneshaw, then via the Ferry to Cape Jervis. Tourism Development of the Fleurieu Way as a primary cross regional tourism route, suitably signposted and promoted, from Wellington, via Strathalbyn, Goolwa, Victor Harbor, Delamere / Cape Jervis, Normanville / Yankalilla, Aldinga, Willunga and McLaren Vale, to Adelaide. Development of the Kangaroo Island South Coast Loop and North Coast Loop as primary regional tourism routes, suitably signposted and promoted, and connected via the Sealink Ferry and the Fleurieu Way to Adelaide and Melbourne. -

SUTTON"'-'-Paoijio Gull

54 The S.A. Ornithologist; April 1, 193f>' SUTTON"'-'-Paoijio Gull. Gabianus pacificus, Pacific Gull. By J. Sutton. Th!~ .hird, the largest of the A~straIian Gulls, which ranges from Shark's Bay; 'IN.A., to Rcckhampton, Q., including 'I'as.. mania, is round about the South Australian coasts and adjacent i~lands, its prominent feature being the large lance-shaped bill. The following is J. Gould's description of the adultc->-" Head, neck, upper part of the back, all the under surface, upper and under tail coverts, white; back and wings, dark slaty black, the secondaries largely tipped with white, primaries black, the innermost slightly tipped with white; tail, .white, the inner web of the outer feather and both webs of' the remainder crossed near the tip with a broad band of black; irides, pearl white; eyelid; yellow; bill, orange stained with blood-red at the tip, in the midst of which in some specimens ate til few blotches of black; legs, yellow; claws, bla<lk." . Professor J. B. Cleland, in Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of South Australia; Vol. XLVII, 1925, pp. 119-126, on The Birds df the Pearson Islands, wrote:-" A full plumaged female bird, in attempting to steal g, bait, got entangled in a fishing line that had been temporarily left unattended. Iris, white; eyelid, orange; base of bill, chrome; distal third of bill, ted with dark grey along the cutting edge; inside of bill, chrome; tongue and floor of mouth between rami of lower bill, orange: g~pe, .orange, except fot a narrow chrome..coloured outer edge; legs, maize yellow; total length, 58.4 cm.; span across out. -

The Birder, No. 255, Spring 2020

e h T The oBfficial mIagaRzine of BDirds SA SEpring 202R 0 No 255 In this Issue Vale Kent Treloar October Campout Linking people with birds What’s happening to in South Australia Adelaide’s trees? A Colourful Pair A Rainbow Lorikeet pair (Photographed by Jeff Groves on River Torrens Linear Park ,June 2020 ) Contents President’s Message ............................................................................................................ 5 Volunteers wanted ................................................................................................................. 6 Vale Kent Treloar ..................................................................................................................... 7 Conservation Sub-Committee Report ............................................................................... 10 What’s happening to Adelaide’s Trees? ............................................................................. 12 Friends of Adelaide International Bird Sanctuary (FAIBS) ............................................. 16 Your help is still needed ...................................................................................................... 17 Bird Watching is Big Business ............................................................................................ 19 Short-tailed Shearwaters in Trouble ................................................................................. 20 Larry’s Birding Trips ............................................................................................................. -

The Official Newsletter of Birds SA Feb 2018 No 245

The BIRDER The official newsletter of Birds SA Feb 2018 No 245 Linking people with birds in South Australia 2 The Birder, February 2018 CONTENTS Australian Crake 2 Diary 4 President’s Message 5 Birds SA Notes & News 6 Fleurieu Birdwatchers 8 Giving them Wings 9 White-bellied Sea Eagle and Osprey Population Surveys 10 Adelaide International Bird Sanctuary/FAIBS 11 A Global Journey: Migratory Birds on the Adelaide Plains 12 A Heron’s Hunting Skills 13 Past General Meetings 15 Future General Meetings 18 Past Excursions 25 Future Excursions 26 Easter Campout 27 Bird Records 30 From the Library 34 About our Association 36 Photographs from members 37 CENTRE INSERT: SAOA HISTORICAL SERIES No: 63, GREGORY MACALISTER MATHEWS PART 3 John Gitsham designed the front page of this issue. Peter Gower took the cover photograph of an Orange Chat in 2015 We welcome a record number of 61 new members who have recently joined the Association. Their names are listed on p35. Birds SA aims to: • Promote the conservation of Australian birds and their habitats. • Encourage interest in, and develop knowledge of, the birds of South Australia. • Record the results of research into all aspects of bird life. • Maintain a public fund called the “Birds SA Conservation Fund” for the specific purpose of supporting the Association’s environmental objectives. The Birder, February, 2018 3 DIARY The following is a list the activities of BIRDS SA, FLEURIEU BIRDERS (FB) and PORT AUGUSTA GROUP (PA) for the next few months. Further details of all these activities can be found later in ‘The Birder’. -

40 Great Short Walks

SHORT WALKS 40 GREAT Notes SOUTH AUSTRALIAN SHORT WALKS www.southaustraliantrails.com 51 www.southaustraliantrails.com www.southaustraliantrails.com NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND Simpson Desert Goyders Lagoon Macumba Strzelecki Desert Creek Sturt River Stony Desert arburton W Tirari Desert Creek Lake Eyre Cooper Strzelecki Desert Lake Blanche WESTERN AUSTRALIA WESTERN Outback Great Victoria Desert Lake Lake Flinders Frome ALES Torrens Ranges Nullarbor Plain NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND Simpson Desert Goyders Lagoon Lake Macumba Strzelecki Desert Creek Gairdner Sturt 40 GREAT SOUTH AUSTRALIAN River Stony SHORT WALKS Head Desert NEW SOUTH W arburton of Bight W Trails Diary date completed Trails Diary date completed Tirari Desert Creek Lake Gawler Eyre Cooper Strzelecki ADELAIDE Desert FLINDERS RANGES AND OUTBACK 22 Wirrabara Forest Old Nursery Walk 1 First Falls Valley Walk Ranges QUEENSLAND A 2 First Falls Plateau Hike Lake 23 Alligator Gorge Hike Blanche 3 Botanic Garden Ramble 24 Yuluna Hike Great Victoria Desert 4 Hallett Cove Glacier Hike 25 Mount Ohlssen Bagge Hike Great Eyre Outback 5 Torrens Linear Park Walk 26 Mount Remarkable Hike 27 The Dutchmans Stern Hike WESTERN AUSTRALI WESTERN Australian Peninsula ADELAIDE HILLS 28 Blinman Pools 6 Waterfall Gully to Mt Lofty Hike Lake Bight Lake Frome ALES 7 Waterfall Hike Torrens KANGAROO ISLAND 0 50 100 Nullarbor Plain 29 8 Mount Lofty Botanic Garden 29 Snake Lagoon Hike Lake 25 30 Weirs Cove Gairdner 26 Head km BAROSSA NEW SOUTH W of Bight 9 Devils Nose Hike LIMESTONE COAST 28 Flinders -

Hindmarsh Island Wetland Complex Pre-Feasibility Fact Sheet

Hindmarsh Island Wetland Complex Pre-Feasibility Fact Sheet The proposal for Hindmarsh Island seeks funding to Improving connectivity at this significant wetland complex undertake feasibility investigations for Reconnecting would restore samphire ecosystems and other vegetation Wetlands on Hindmarsh Island. The proposal aims to communities that provide critical habitat for birds, fish and improve connectivity by removing barriers to flow at a other species, including a number of threatened species. number of sites to allow water to flow westward through There are also opportunities to create estuarine conditions the Hindmarsh Island wetland complex. Since the for fish passage at Goolwa Channel. This proposal would introduction of agriculture to the island, wetland channels contribute to achieving the long term vision for Hindmarsh have become blocked due to the construction of roads and Island, developed by the Hindmarsh Island Landcare earthen mounds. The proposed scope of work includes Group, which has coordinated the planting of over 300,000 replacing culverts, installing new culverts and undertaking plants in the last 12 years. other on-ground works to remove blockages to flow. The Hindmarsh Island wetlands are large temporary The feasibility stage of this project would incorporate a wetlands forming part of the Lake Alexandrina fringing detailed assessment of on-ground works requirements to wetland complex. The wetland complex includes wetland improve connectivity throughout the wetlands, as well as basins, a number of interconnecting channels and creeks opportunities for creating estuarine conditions. and an estuary which extends throughout the eastern half of the island. The wetlands have a direct connection to Lakes Alexandrina and Albert and therefore water levels reflect lake depths. -

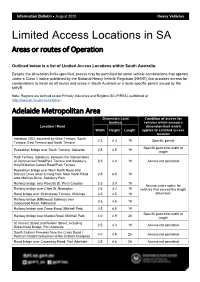

Consolidated Table of Limited Access Locations for SA

Information Bulletin August 2020 Heavy Vehicles Limited Access Locations in SA Areas or routes of Operation Outlined below is a list of Limited Access Locations within South Australia. Despite the dimension limits specified, access may be permitted for some vehicle combinations that operate under a Class 1 notice published by the National Heavy Vehicle Regulator (NHVR) that provides access for combinations to travel on all routes and areas in South Australia or a route specific permit issued by the NHVR. Note: Regions are defined as per Primary Industries and Regions SA (PIRSA), published at http://www.pir.sa.gov.au/regions. Adelaide Metropolitan Area Dimension Limit Condition of access for (metres) vehicles which exceed a Location / Road dimension limit which Width Height Length applies to a limited access location Adelaide CBD, bounded by West Terrace, South 2.5 4.3 19 Specific permit Terrace, East Terrace and North Terrace Specific permit for width or Pedestrian bridge over South Terrace, Adelaide 2.5 4.5 19 length Park Terrace, Salisbury, between the intersections of Commercial Road/Park Terrace and Salisbury 2.5 4.3 19 Access not permitted Hwy/Waterloo Corner Road/Park Terrace Pedestrian bridge over Main North Road and Malinya Drive when turning from Main North Road 3.5 4.5 19 onto Malinya Drive, Salisbury Park Railway bridge over Rosetta St, West Croydon 2.5 3.0 19 Access under notice for Railway bridge over Chief St, Brompton 2.5 3.2 19 vehicles that exceed the length Road bridge over St Andrews Terrace, Willunga 3.5 4.5 19 dimension -

CHAPTER SIX Case Study of the Ngarrindjeri of South Australia

CHAPTER SIX Case study of the Ngarrindjeri of South Australia 6.1 Introduction This thesis presents the conceptual argument that corporatised tourism and capitalist globalisation bring about social and environmental problems that inspire the formation of alternative tourisms and perhaps even alternative globalisations. After exploring some of the issues arising at the interstices of Indigenous peoples, globalisation and tourism, this chapter explores the experience of the Ngarrindjeri community of South Australia which demonstrates some of the dynamics playing out in a local context. The Ngarrindjeri are the founders of a pioneering facility, Camp Coorong Race Relations and Cultural Education Centre, fostering reconciliation tourism which is dedicated to healing the divide between non-Indigenous and Indigenous Australians. The Ngarrindjeri have also experienced grave problems with capitalist development and tourism pressures. In response to these difficulties, the Ngarrindjeri have continued to operate Camp Coorong while simultaneously establishing a political agenda to assert their Indigenous rights. This analysis suggests that, for alternative tourism to be effective in humanising tourism and 289 globalisation, human rights agendas are required to shift existing power dynamics. Before delving into these issues, it is necessary to first examine the impacts of globalisation and corporatised tourism on Indigenous peoples in the global community. 6.2 Impacts of globalisation and tourism on Indigenous communities Globalisation from an Indigenous perspective brings issues of power and exploitation to the fore. As Stewart-Harawira asserts, Indigenous people view the origins of globalisation not as a natural progress from enlightenment ideals but rather as the offspring of imperialism and colonialism with its history of “…genocide and dispossession, of violence and loss” (2005b, p. -

Alexandrina Bird Trails Strathalbyn Langhorne Tailem N Mclaren Vale Creek Bend

alexandrina.com visit www. KILOMETRES B37 Site Marker Site 10 5 4 3 2 1 0 Conservation Park/Forest Conservation Murray Mouth Murray ctor Harbor ctor Vi 3 Unsealed Road Unsealed 2 5 Sealed Road Sealed Semaschko Rd 8 Port Elliot Port 4 7 1 Main Road Main Barrage Rd Barrage Middleton R d 6 r e De v n Information Centre Information Randell Rd Randell 9 Hindmarsh Island Hindmarsh Landmark Kessel Rd Kessel Clayton Bay Clayton Goolwa 1 Proceed with caution with Proceed Milang West Trail West Milang Creek Milang Township & East Trail East & Township Milang Currency 1 1 Strathalbyn Woodland Trail Woodland Strathalbyn M i l a Alexandrina Bushland Trail B Trail Bushland Alexandrina n g - A13 C l Alexandrina Bushland Trail A Trail Bushland Alexandrina a CP y 5 t o n Scott R Goolwa Wetland Trail Wetland Goolwa D Milang d e 1 Winery Rd Winery Gould Rd Gould 2 e 2 p Bird Trail Legend Trail Bird 2 C Finniss - Clayton Rd Clayton - Finniss r e e Lakes Rd Lakes 4 Goolwa Rd Goolwa k Finniss R d 3 Finniss Milang Rd Milang Finniss Lake Plains Rd B37 3 B u l olderol Rd olderol T l C d 4 R r Nurragi Cons Res Cons Nurragi a t e i k 3 g e n a k N Arthur Rd Arthur R d A 1 d 2 l R e t x a a Compass Mt n l Cox Scrub CP Scrub Cox d F A13 r i n l a Dog Lake Rd Lake Dog a R n 3 d g 1 i 3 Mt Magnificent CP Magnificent Mt S CP Finniss M B t Bullock Hill CP Hill Bullock M l a 2 Lee Rd Lee c a k g f n e l 4 l i o B45 f i w Ashbourne c s e C n k Langhorne Creek Langhorne t R R Ashbourne Rd Ashbourne d d M d R l l i H c e H t a g a d r g 4 o C o A13 k R d W KANGAROO ISLAND -

For Tours, Accommodation & Kangaroo Island Ferry Bookings & Enquiries

SECOND VALLEY YANKALILLA Tourism Accredited business Wheelchair / disabled friendly Pet friendly Updated 24/6/18 THIS BROCHURE IS A GUIDE ONLY, PRICES & TIMES MAY VARY Lilla’s Leonards Mill Hotel & Bar 117 Main South Road, Tel: (08) 8558 2525 Emerald Chinese RESTAURANTS VICTOR HARBOR McCracken Country Club Restaurant Just Penny’s Nicolas Baudin’s Restaurant 7869 Main South Road, Second Valley 104 Main South Road, Tel: 0408 031 659 Anchorage Café – Restaurant- Main Port Elliot Road, Victor Harbor Coffee and lunch 11am - to 3pm. Wednesday to & Clubhouse Bistro Tel: (08) 8552 4474 Yankalilla Hotel Wine Bar Sunday. Dinner 6pm to 10pm Friday and Saturday. McCracken Drive, Victor Harbor Hotel Crown 105 Main South Road, Tel: (08) 8558 2011 Extended trading hours from Boxing day - see website With sweeping views across the lush fairways of the 2 Ocean Street, Victor Harbor for details. Regional dining experience, showcasing 21 Flinders Parade, Victor Harbor golf course, McCracken Country Club offers Baudin’s Open 7 Days- Breakfast, lunch & dinner. House roast- Tel: (08) 8552 1022 the best of the Fleurieu. Alfresco dining on deck. Restaurant & the Clubhouse Bistro. They boast www.leonardsmill.com ed specialty coffee. Unique boat bar, alfresco dining fabulous Australian cuisine, which is tailor-made to Pa’s Fish Cafe Tel: (08) 8598 4184 during summer. Open log fire during winter. Private the season, using the freshest delicacies on offer. function room available. 61 Franklin Parade, Victor Harbor Our restaurant offers an extensive wine list, promoting Tel: (08) 8552 5970 wines from local Southern Vale wineries & other Tel: (08) 8552 1055 Wines of the Fleurieu Cellar www.anchorageseafronthotel.com renowned Australian wine regions. -

“Secret Women's Business”: Indigenous Rights

“SECRET WOMEN’S BUSINESS”: INDIGENOUS RIGHTS, ANTHROPOLOGY, AND THE HINDMARSH ISLAND BRIDGE CONTROVERSY 1 What makes something a secret? What is worth keeping secret? Should secrets be revealed? 2 The Setting for a Dispute Goolwa, South Australia, & Hindmarsh Island 3 4 the area “is crucial for the reproduction of the Ngarrindjeri people and the cosmos which supports their existence. The waters are a life force to the Ngarrindjeri women, whether past or present, and should anything cover these waters, then the strength there will be taken from the Ngarrindjeri women and they will become very ill”. Native Title Aboriginality, gender, secrecy, the judicial system, colonial history, economic development, cultural conflict—anthropology 5 Secret Women’s Business opposing Aboriginal views The Hindmarsh Island Royal Commission Prime Minister John Howard, the Hindmarsh Island Bridge Act (1997), bridge completed in March of 2001. Dr. Deane Fergie, anthropologist at the University of Adelaide 6 Confidential: to be read by women only Rod Lucas Neil Draper 7 The Roots of Aboriginal Dissent Aboriginal women who claimed that secret women’s business was a hoax ignorant of the origins and nature of Ngarrindjeri beliefs knowledge selectively distributed within a community “no point in reliving the past” Christian converts Anthropologists at War over the Truth male anthropologists ethics a feminist agenda? 8 Anthropology and the Culture Wars 2010, Government of South Australia: “secret women’s business” was real and authentic. Tom Trevorrow: “We may use the bridge to access our land and waters but culturally and morally we cannot come to terms with this bridge”. 9 Australia’s culture wars political correctness run amok “the willingness of white people to believe the Aboriginal women, marked the high-water mark of politically correct soft-headedness and sentimentality” (Simons, 2003) Ron Brunton and Roger Sandall Roger Sandall: The Culture Cult “designer tribalism” & “romantic primitivism” fantasies held by “spoiled white urbanites”. -

Culture in a Sealed Envelope: the Concealment of Australian Aboriginal Heritage and Tradition in the Hindmarsh Island Bridge Affair

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institu... June 1999 v5 i2 p193(1) Page 1 Culture in a sealed envelope: the concealment of Australian aboriginal heritage and tradition in the Hindmarsh Island Bridge affair. by James F. Weiner This article analyses the Hindmarsh Island Bridge controversy in South Australia to argue that the legislative requirements for the presentation of indigenous culture and society conceal the extent to which this culture and society are themselves elicited by the very form and process of the legislation. The anthropological task of articulating a relational view of culture and identity in a legal and political domain which makes invisible the relational bases of its own procedures of knowledge and identity formation is one of the main challenges that emerges from the controversy. This article examines the versions of Ngarrindjeri culture and religion that were aired during the Royal Commission into the Hindmarsh Island Bridge in 1995 and speculates on the failure of both anthropology and the state to consider the relational nature of social knowledge and culture. © COPYRIGHT 1999 Royal Anthropological Institute In such cases, it is difficult or impossible to demonstrate ownership of land, mythological and religious validation of Anthropology might at first seem to garner some hope and the sacred status of certain sites or objects, and continuity optimism from legislation that protects the cultural heritage of tradition. Given that the Australian public has a highly of indigenous peoples and gives them ways to