The Go Programming Language Phrasebook / David Chisnall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Safe, Fast and Easy: Towards Scalable Scripting Languages

Safe, Fast and Easy: Towards Scalable Scripting Languages by Pottayil Harisanker Menon A dissertation submitted to The Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Baltimore, Maryland Feb, 2017 ⃝c Pottayil Harisanker Menon 2017 All rights reserved Abstract Scripting languages are immensely popular in many domains. They are char- acterized by a number of features that make it easy to develop small applications quickly - flexible data structures, simple syntax and intuitive semantics. However they are less attractive at scale: scripting languages are harder to debug, difficult to refactor and suffers performance penalties. Many research projects have tackled the issue of safety and performance for existing scripting languages with mixed results: the considerable flexibility offered by their semantics also makes them significantly harder to analyze and optimize. Previous research from our lab has led to the design of a typed scripting language built specifically to be flexible without losing static analyzability. Inthis dissertation, we present a framework to exploit this analyzability, with the aim of producing a more efficient implementation Our approach centers around the concept of adaptive tags: specialized tags attached to values that represent how it is used in the current program. Our frame- work abstractly tracks the flow of deep structural types in the program, and thuscan ii ABSTRACT efficiently tag them at runtime. Adaptive tags allow us to tackle key issuesatthe heart of performance problems of scripting languages: the framework is capable of performing efficient dispatch in the presence of flexible structures. iii Acknowledgments At the very outset, I would like to express my gratitude and appreciation to my advisor Prof. -

Comparative Studies of Programming Languages; Course Lecture Notes

Comparative Studies of Programming Languages, COMP6411 Lecture Notes, Revision 1.9 Joey Paquet Serguei A. Mokhov (Eds.) August 5, 2010 arXiv:1007.2123v6 [cs.PL] 4 Aug 2010 2 Preface Lecture notes for the Comparative Studies of Programming Languages course, COMP6411, taught at the Department of Computer Science and Software Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and Computer Science, Concordia University, Montreal, QC, Canada. These notes include a compiled book of primarily related articles from the Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia [24], as well as Comparative Programming Languages book [7] and other resources, including our own. The original notes were compiled by Dr. Paquet [14] 3 4 Contents 1 Brief History and Genealogy of Programming Languages 7 1.1 Introduction . 7 1.1.1 Subreferences . 7 1.2 History . 7 1.2.1 Pre-computer era . 7 1.2.2 Subreferences . 8 1.2.3 Early computer era . 8 1.2.4 Subreferences . 8 1.2.5 Modern/Structured programming languages . 9 1.3 References . 19 2 Programming Paradigms 21 2.1 Introduction . 21 2.2 History . 21 2.2.1 Low-level: binary, assembly . 21 2.2.2 Procedural programming . 22 2.2.3 Object-oriented programming . 23 2.2.4 Declarative programming . 27 3 Program Evaluation 33 3.1 Program analysis and translation phases . 33 3.1.1 Front end . 33 3.1.2 Back end . 34 3.2 Compilation vs. interpretation . 34 3.2.1 Compilation . 34 3.2.2 Interpretation . 36 3.2.3 Subreferences . 37 3.3 Type System . 38 3.3.1 Type checking . 38 3.4 Memory management . -

Static Analyses for Stratego Programs

Static analyses for Stratego programs BSc project report June 30, 2011 Author name Vlad A. Vergu Author student number 1195549 Faculty Technical Informatics - ST track Company Delft Technical University Department Software Engineering Commission Ir. Bernard Sodoyer Dr. Eelco Visser 2 I Preface For the successful completion of their Bachelor of Science, students at the faculty of Computer Science of the Technical University of Delft are required to carry out a software engineering project. The present report is the conclusion of this Bachelor of Science project for the student Vlad A. Vergu. The project has been carried out within the Software Language Design and Engineering Group of the Computer Science faculty, under the direct supervision of Dr. Eelco Visser of the aforementioned department and Ir. Bernard Sodoyer. I would like to thank Dr. Eelco Visser for his past and ongoing involvment and support in my educational process and in particular for the many opportunities for interesting and challenging projects. I further want to thank Ir. Bernard Sodoyer for his support with this project and his patience with my sometimes unconvential way of working. Vlad Vergu Delft; June 30, 2011 II Summary Model driven software development is gaining momentum in the software engi- neering world. One approach to model driven software development is the design and development of domain-specific languages allowing programmers and users to spend more time on their core business and less on addressing non problem- specific issues. Language workbenches and support languages and compilers are necessary for supporting development of these domain-specific languages. One such workbench is the Spoofax Language Workbench. -

Blossom: a Language Built to Grow

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College Mathematics, Statistics, and Computer Science Honors Projects Mathematics, Statistics, and Computer Science 4-26-2016 Blossom: A Language Built to Grow Jeffrey Lyman Macalester College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/mathcs_honors Part of the Computer Sciences Commons, Mathematics Commons, and the Statistics and Probability Commons Recommended Citation Lyman, Jeffrey, "Blossom: A Language Built to Grow" (2016). Mathematics, Statistics, and Computer Science Honors Projects. 45. https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/mathcs_honors/45 This Honors Project - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Mathematics, Statistics, and Computer Science at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mathematics, Statistics, and Computer Science Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. In Memory of Daniel Schanus Macalester College Department of Mathematics, Statistics, and Computer Science Blossom A Language Built to Grow Jeffrey Lyman April 26, 2016 Advisor Libby Shoop Readers Paul Cantrell, Brett Jackson, Libby Shoop Contents 1 Introduction 4 1.1 Blossom . .4 2 Theoretic Basis 6 2.1 The Potential of Types . .6 2.2 Type basics . .6 2.3 Subtyping . .7 2.4 Duck Typing . .8 2.5 Hindley Milner Typing . .9 2.6 Typeclasses . 10 2.7 Type Level Operators . 11 2.8 Dependent types . 11 2.9 Hoare Types . 12 2.10 Success Types . 13 2.11 Gradual Typing . 14 2.12 Synthesis . 14 3 Language Description 16 3.1 Design goals . 16 3.2 Type System . 17 3.3 Hello World . -

BEGINNING OBJECT-ORIENTED PROGRAMMING with JAVASCRIPT Build up Your Javascript Skills and Embrace PRODUCT Object-Oriented Development for the Modern Web INFORMATION

BEGINNING OBJECT-ORIENTED PROGRAMMING WITH JAVASCRIPT Build up your JavaScript skills and embrace PRODUCT object-oriented development for the modern web INFORMATION FORMAT DURATION PUBLISHED ON Instructor-Led Training 3 Days 22nd November, 2017 DESCRIPTION OUTLINE JavaScript has now become a universal development Diving into Objects and OOP Principles language. Whilst offering great benefits, the complexity Creating and Managing Object Literals can be overwhelming. Defining Object Constructors Using Object Prototypes and Classes In this course we show attendees how they can write Checking Abstraction and Modeling Support robust and efficient code with JavaScript, in order to Analyzing OOP Principles in JavaScript create scalable and maintainable web applications that help developers and businesses stay competitive. Working with Encapsulation and Information Hiding Setting up Strategies for Encapsulation LEARNING OUTCOMES Using the Meta-Closure Approach By completing this course, you will: Using Property Descriptors Implementing Information Hiding in Classes • Cover the new object-oriented features introduced as a part of ECMAScript 2015 Inheriting and Creating Mixins • Build web applications that promote scalability, Implementing Objects, Inheritance, and Prototypes maintainability and usability Using and Controlling Class Inheritance • Learn about key principles like object inheritance and Implementing Multiple Inheritance JavaScript mixins Creating and Using Mixins • Discover how to skilfully develop asynchronous code Defining Contracts with Duck Typing within larger JS applications Managing Dynamic Typing • Complete a variety of hands-on activities to build Defining Contracts and Interfaces up your experience of real-world challenges and Implementing Duck Typing problems Comparing Duck Typing and Polymorphism WHO SHOULD ATTEND Advanced Object Creation Mastering Patterns, Object Creation, and Singletons This course is for existing developers who are new to Implementing an Object Factory object-oriented programming in the JavaScript language. -

4500/6500 Programming Languages What Are Types? Different Definitions

What are Types? ! Denotational: Collection of values from domain CSCI: 4500/6500 Programming » integers, doubles, characters ! Abstraction: Collection of operations that can be Languages applied to entities of that type ! Structural: Internal structure of a bunch of data, described down to the level of a small set of Types fundamental types ! Implementers: Equivalence classes 1 Maria Hybinette, UGA Maria Hybinette, UGA 2 Different Definitions: Types versus Typeless What are types good for? ! Documentation: Type for specific purposes documents 1. "Typed" or not depends on how the interpretation of the program data representations is determined » Example: Person, BankAccount, Window, Dictionary » When an operator is applied to data objects, the ! Safety: Values are used consistent with their types. interpretation of their values could be determined either by the operator or by the data objects themselves » Limit valid set of operation » Languages in which the interpretation of a data object is » Type Checking: Prevents meaningless operations (or determined by the operator applied to it are called catch enough information to be useful) typeless languages; ! Efficiency: Exploit additional information » those in which the interpretation is determined by the » Example: a type may dictate alignment at at a multiple data object itself are called typed languages. of 4, the compiler may be able to use more efficient 2. Sometimes it just means that the object does not need machine code instructions to be explicitly declared (Visual Basic, Jscript -

Multiparadigm Programming with Python 3 Chapter 5

Multiparadigm Programming with Python 3 Chapter 5 H. Conrad Cunningham 7 September 2018 Contents 5 Python 3 Types 2 5.1 Chapter Introduction . .2 5.2 Type System Concepts . .2 5.2.1 Types and subtypes . .2 5.2.2 Constants, variables, and expressions . .2 5.2.3 Static and dynamic . .3 5.2.4 Nominal and structural . .3 5.2.5 Polymorphic operations . .4 5.2.6 Polymorphic variables . .5 5.3 Python 3 Type System . .5 5.3.1 Objects . .6 5.3.2 Types . .7 5.4 Built-in Types . .7 5.4.1 Singleton types . .8 5.4.1.1 None .........................8 5.4.1.2 NotImplemented ..................8 5.4.2 Number types . .8 5.4.2.1 Integers (int)...................8 5.4.2.2 Real numbers (float)...............9 5.4.2.3 Complex numbers (complex)...........9 5.4.2.4 Booleans (bool)..................9 5.4.2.5 Truthy and falsy values . 10 5.4.3 Sequence types . 10 5.4.3.1 Immutable sequences . 10 5.4.3.2 Mutable sequences . 12 5.4.4 Mapping types . 13 5.4.5 Set Types . 14 5.4.5.1 set ......................... 14 5.4.5.2 frozenset ..................... 14 5.4.6 Other object types . 15 1 5.5 What Next? . 15 5.6 Exercises . 15 5.7 Acknowledgements . 15 5.8 References . 16 5.9 Terms and Concepts . 16 Copyright (C) 2018, H. Conrad Cunningham Professor of Computer and Information Science University of Mississippi 211 Weir Hall P.O. Box 1848 University, MS 38677 (662) 915-5358 Browser Advisory: The HTML version of this textbook requires a browser that supports the display of MathML. -

Reducing Costs with Structural Typing.Key

Reducing Costs with StructuralDuck Typing 1 “Duck Typing” In computer programming with object-oriented programming languages, duck typing is a layer of programming language and design rules on top of typing. Typing is concerned withvacuous! assigning a type to any object. Duckunnecessary! typing is concerned with establishing the suitability of an object for some purpose. With normalclass typing, suitability is assumed to be determined by an object’s typeclass only. With nominal typing, suitability is assumed to depend on the claims made when the object was created In contrast in duck typing, an object's suitability is determined by the presence of certain methods and properties (with appropriate meaning), rather than the actual type of the object. The name of the concept refers to the duck test, attributed to James Whitcomb Riley, which may be phrased as follows: When I see a bird that walks like a duck and swims like a duck and quacks like a duck, I call that bird a duck.[1] Some confusion present here 2 Metz: • Duck types are public interfaces that are not tied to any specific class • A Ruby object is like a partygoer at a masquerade ballGrace that changes masks to suit the theme. It can expose a different face to every viewer; it can implement many different interfaces. • … an object’s type is in the eye of the beholder. Users of an object need not, and should not, be concerned about its class. • It’s not what an object is that matters, it’s what it does. 3 Structural vs. Nominal • Structural typing (Duck Typing) ✦ a type T describes a set of properties (so, it’s like a predicate). -

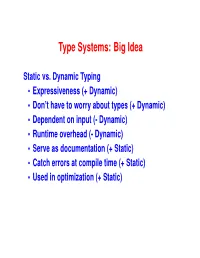

Type Systems: Big Idea

Type Systems: Big Idea Static vs. Dynamic Typing • Expressiveness (+ Dynamic) • Don’t have to worry about types (+ Dynamic) • Dependent on input (- Dynamic) • Runtime overhead (- Dynamic) • Serve as documentation (+ Static) • Catch errors at compile time (+ Static) • Used in optimization (+ Static) Type Systems: Big Idea • Undecideability forces tradeoff: – Dynamic or – Approximate or – Non-terminating • Example: array bounds checking – Occasional negative consequences: e.g., Heartbleed Type Systems: Mechanics • Monomorphic and Polymorphic Types • Types, Type Constructors, Quantified Types (8«: ) • Kinds () classify types: – well-formed, – types (*), – type constructors: µ • Type Environments: type identifiers ! kinds • Typing Rules – Introduction and Elimination forms • Type Checking • Induction and Recursion Hindley-Milner Type Inference: Big Idea • Inferred vs Declared Types – Advantages of Inference: write fewer types, infer more general types. – Advantages of Declarations: better documentations, more general type system. • Canonical example of static analysis: – Proving properties of programs based only on text of program. – Useful for compilers and security analysis. Hindley-Milner Type Inference: Mechanics • Use fresh type variables to represent unknown types • Generate constraints that collect clues • Solve constraints just before introducing quantifiers • Compromises to preserve decideability: – Only generalize lets and top-level declarations – Polymorphic functions aren’t first-class Module Systems a la SML: Big Ideas • “Programming-in-the-large” -

Javascript: the First 20 Years

JavaScript: The First 20 Years ALLEN WIRFS-BROCK, Wirfs-Brock Associates, Inc., USA BRENDAN EICH, Brave Software, Inc., USA Shepherds: Sukyoung Ryu, KAIST, South Korea Richard P. Gabriel: poet, writer, computer scientist How a sidekick scripting language for Java, created at Netscape in a ten-day hack, ships first as a de facto Web standard and eventually becomes the world’s most widely used programming language. This paper tells the story of the creation, design, evolution, and standardization of the JavaScript language over the period of 1995–2015. But the story is not only about the technical details of the language. It is also the story of how people and organizations competed and collaborated to shape the JavaScript language which dominates the Web of 2020. CCS Concepts: • General and reference ! Computing standards, RFCs and guidelines; • Information systems ! World Wide Web; • Social and professional topics ! History of computing; History of programming languages; • Software and its engineering ! General programming languages; Scripting languages. Additional Key Words and Phrases: JavaScript, ECMAScript, Standards, Web browsers, Browser game theory, History of programming languages ACM Reference Format: Allen Wirfs-Brock and Brendan Eich. 2020. JavaScript: The First 20 Years. Proc. ACM Program. Lang. 4, HOPL (June 2020), 190 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3386327 1 INTRODUCTION In 2020, the World Wide Web is ubiquitous with over a billion websites accessible from billions of Web-connected devices. Each of those devices runs a Web browser or similar program which is able to process and display pages from those sites. The majority of those pages embed or load source code written in the JavaScript programming language. -

=5Cm Cunibig Concepts in Programming Languages

Concepts in Programming Languages Alan Mycroft1 Computer Laboratory University of Cambridge 2016–2017 (Easter Term) www.cl.cam.ac.uk/teaching/1617/ConceptsPL/ 1Acknowledgement: various slides are based on Marcelo Fiore’s 2013/14 course. Alan Mycroft Concepts in Programming Languages 1 / 237 Practicalities I Course web page: www.cl.cam.ac.uk/teaching/1617/ConceptsPL/ with lecture slides, exercise sheet and reading material. These slides play two roles – both “lecture notes" and “presentation material”; not every slide will be lectured in detail. I There are various code examples (particularly for JavaScript and Java applets) on the ‘materials’ tab of the course web page. I One exam question. I The syllabus and course has changed somewhat from that of 2015/16. I would be grateful for comments on any remaining ‘rough edges’, and for views on material which is either over- or under-represented. Alan Mycroft Concepts in Programming Languages 2 / 237 Main books I J. C. Mitchell. Concepts in programming languages. Cambridge University Press, 2003. I T.W. Pratt and M. V.Zelkowitz. Programming Languages: Design and implementation (3RD EDITION). Prentice Hall, 1999. ? M. L. Scott. Programming language pragmatics (4TH EDITION). Elsevier, 2016. I R. Harper. Practical Foundations for Programming Languages. Cambridge University Press, 2013. Alan Mycroft Concepts in Programming Languages 3 / 237 Context: so many programming languages Peter J. Landin: “The Next 700 Programming Languages”, CACM (published in 1966!). Some programming-language ‘family trees’ (too big for slide): http://www.oreilly.com/go/languageposter http://www.levenez.com/lang/ http://rigaux.org/language-study/diagram.html http://www.rackspace.com/blog/ infographic-evolution-of-computer-languages/ Plan of this course: pick out interesting programming-language concepts and major evolutionary trends. -

Typescript Interview Questions

By OnlineInterviewQuestions.com Typescript Interview Questions What is Typescript? Typescript is a superset of JavaScript which primarily provides optional static typing, classes, and interfaces. We have written some Refined interview questions on Typescript that helps developers to crack interview on TypeScript. Below are the list of some Typescript Interview Questions and their answers that may be asked by an interviewer in your interview Q1. What is Typescript? Typescript is a free and open-source programming language which is designed and developed by Microsoft. It was designed by Anders Hejlsberg at Microsoft. Typescript is a superset of JavaScript which primarily provides optional static typing, classes and interfaces. Typescript is compiled to provide clean and simple JavaScript code which runs on any browser. It allows JavaScript developers for using highly productive development tools and practices like static checking and code refactoring. Differences between Typescript and JavaScript are 1. JavaScript don’t support Es6 while Typescript supports . 2. JavaScript build up reusable components by using unctions and prototype-based inheritance while Typescript supports Classes that allow programmer to think in more object oriented way . 3. JavaScript don’t have any interfaces while Typescript has interfaces. 4. There is no static typing in JavaScript whereas there is static typing in Typescript. 5. JavaScript has no optional parameter feature while Typescript has optional parameter feature. Q2. List some features of Typescript? Features of Typescript are:- Typescript can be compiled to all major versions of Javascript(ES3,ES5,ES6,ES7). Typescript can be used for cross –browser development and is an open source project. Typescript is a superset of JavaScript that provides typed nature to your code.