Erectile Dysfunction in Family Practice: The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding Icd-10-Cm and Icd-10-Pcs 3Rd Edition Download Free

UNDERSTANDING ICD-10-CM AND ICD-10-PCS 3RD EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Mary Jo Bowie | 9781305446410 | | | | | International Classification of Diseases, (ICD-10-CM/PCS) Transition - Background Palmer B. Manual placenta removal. A: Understanding ICD-10-CM and ICD-10-PCS 3rd edition International Classification of Diseases ICD is a common framework and language to report, compile, use and compare health information. Psychoanalysis Adlerian therapy Analytical therapy Mentalization-based treatment Transference focused psychotherapy. Hysteroscopy Vacuum aspiration. Every code begins with an alpha character, which is indicative of the chapter to which the code is classified. Search Compliance Understanding BC, resilience standards and how to comply Follow these nine steps to first identify relevant business continuity and resilience standards and, second, launch a successful While many coders use ICD lookup software to help them, referring to an ICD code book is invaluable to build an understanding of the classification system. Pregnancy test Leopold's maneuvers Prenatal testing. Endoscopy : Colonoscopy Anoscopy Capsule endoscopy Enteroscopy Proctoscopy Sigmoidoscopy Abdominal ultrasonography Defecography Double-contrast barium enema Endoanal ultrasound Enteroclysis Lower gastrointestinal series Small-bowel follow-through Transrectal ultrasonography Virtual colonoscopy. Psychosurgery Lobotomy Bilateral cingulotomy Multiple subpial transection Hemispherectomy Corpus callosotomy Anterior temporal lobectomy. While codes in sections are structured similarly to the Medical and Surgical section, there are a few exceptions. Send Feedback Do you have Understanding ICD-10-CM and ICD-10-PCS 3rd edition on the new website? Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. D Radiation oncology. Stem cell transplantation Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. The primary distinctions are:. Palmer Joseph C. -

Laboratory Guide 2021 Valid from 1St January 2021 Cover: Daniel Odukoya, BMS, Laboratory Supervisor Within Molecular Pathology Handling PCR Samples

Laboratory Guide 2021 Valid from 1st January 2021 Cover: Daniel Odukoya, BMS, Laboratory Supervisor within Molecular Pathology handling PCR samples. TAP4557/22-11-20/V3 Laboratory Guide 2021 Valid from 1st January 2021 TDL Customer Charter We are committed to being the most helpful pathology service in the UK. Our goal is always to provide a high level of service to our customers, who request pathology services, for their patients. This is a philosophy shared by all Sonic Healthcare Pathology practices. We are medically led, and patients are our first concern. We always try to look to improve our operational expertise, and we strive to provide professional leadership within our specialities. We promise to provide easy access to our pathology services • We will always provide a friendly, helpful service. • Our automated laboratory departments operate 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and we aim to achieve, or improve, our published turnaround times. • Our medical consultants and laboratory teams are available to provide additional clarification, advice or information for tests or results. We promise to help you • We invest in technical and operational excellence, with an extensive test repertoire, to ensure access to a leading-edge laboratory service. • We return results using the reporting method choice, in an as organised and safe way as possible. We promise to support the communities we work in • We do our utmost to provide a service, even during extreme external disruptions beyond our control. • We are committed to our staff’s continued professional development. • We have an organised programme to provide young people with work experience. -

Effective for Cases Diagnosed January 1, 2016 and Later

POLICY AND PROCEDURE MANUAL FOR REPORTING FACILITIES May 2016 Effective For Cases Diagnosed January 1, 2016 and Later Indiana State Cancer Registry Indiana State Department of Health 2 North Meridian Street, Section 6-B Indianapolis, IN 46204-3010 TABLE OF CONTENTS INDIANA STATE DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH STAFF ............................................................................. viii INDIANA STATE DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH CANCER REGISTRY STAFF .......................................... ix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................................................................................................ x INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................... 1 A. Background ..................................................................................................................................... 1 B. Purpose .......................................................................................................................................... 1 C. Definitions ....................................................................................................................................... 1 D. Reference Materials........................................................................................................................ 1 E. Consultation .................................................................................................................................... 2 F. Output ............................................................................................................................................ -

Tender Document for Selection of Implementation Support Agency (TPA) for Providing Support Services for the Implementation of Health Scheme (PM-JAY, AAUY and SGHS)

Tender Document for Selection of Implementation Support Agency (TPA) For providing support services for the implementation of Health Scheme (PM-JAY, AAUY and SGHS) In the State of Uttarakhand August 2021 Volume II: About Health Schemes (AB-PMJAY, AAUY and SGHS) Schedule of Requirements, Specifications, Scope of work and Allied Technical Details Tender for Selection of Implementation Support Agency For providing support services for the implementation of Health Scheme (PM-JAY, AAUY and SGHS) In the State of Uttarakhand Table of Contents Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Definitions and Interpretations .................................................................................................................... 6 Disclaimer................................... ................................................................................................................ 11 1. Name of the Scheme ............................................................................................................................. 13 2. Objectives of the Scheme ...................................................................................................................... 13 3. Health Scheme Beneficiaries and Beneficiary Family Unit .................................................................... 13 4. Benefit Cover and Benefit Limit ............................................................................................................ -

Program Book Welcome

North Central Section of the AUA, Inc. 92nd Annual Meeting September 5 - 8, 2018 Fairmont Chicago, Millennium Park Chicago, Illinois PROGRAM BOOK WELCOME Table of Contents Schedule at a Glance 2 Hotel Directory 6 Promotional Partners 7 Exhibitors 8 Industry Satellite Symposium Events 9 CME Information 10 2017 - 2018 Board of Directors 13 2017 - 2018 Committee Listing 14 NCS Representatives to AUA Committees 17 Past Presidents and Annual Meeting Sites 18 Board of Directors and Committee Meetings 21 General Meeting Information 22 Evening Functions 23 Speaker Information 24 Program 25 Wednesday, September 5 25 Thursday, September 6 29 Friday, September 7 50 Saturday, September 8 67 Participant Index 78 Podiums 87 Posters 190 Annual Business Meeting Agenda 223 Membership Candidates and Transfers 224 Membership Summary Report 225 Proposed Bylaws Changes 226 Bylaws 228 In Memoriam 240 Award Recipients 241 NCS Urology Residency Programs 247 AUA Officers 250 AUA Foundation Research Scholars 250 POLICY: Filming, Photography, Audio Recording, and Cell Phones No attendee/visitor at the NCS 92nd Annual Meeting may record, film, tape, photograph, interview, or use any other such media during any presentation, display, or exhibit without the express, advance approval of the NCS Executive Director. The policy applies to all NCS members, nonmembers, guests, and exhibitors, as well as members of the print, online, or broadcast media. Back to Table of Contents 1 Schedule at a Glance WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 5, 2018 7:00 a.m. - 5:30 p.m. Registration/Information Desk Hours: International Foyer 7:00 a.m. - 5:30 p.m. Speaker Ready Room Hours: Royal Room 7:30 a.m. -

Laboratory Guide 2020 Valid from 1St January 2020 TAP4232/31-12-19/V1C Laboratory Guide 2020 Valid from 1St January 2020

Laboratory Guide 2020 Valid from 1st January 2020 TAP4232/31-12-19/V1C Laboratory Guide 2020 Valid from 1st January 2020 TDL Customer Charter We are committed to being the most helpful pathology service in the UK. Our goal is always to provide a high level of service to our customers, who request pathology services, for their patients. This is a philosophy shared by all Sonic Healthcare Pathology practices. We are medically led, and patients are our first concern. We always try to look to improve our operational expertise, and we strive to provide professional leadership within our specialities. We promise to provide easy access to our pathology services • We will always provide a friendly, helpful service. • Our automated laboratory departments operate 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and we aim to achieve, or improve, our published turnaround times. • Our medical consultants and laboratory teams are available to provide additional clarification, advice or information for tests or results. We promise to help you • We invest in technical and operational excellence, with an extensive test repertoire, to ensure access to a leading-edge laboratory service. • We return results using the reporting method choice, in an as organised and safe way as possible. We promise to support the communities we work in • We do our utmost to provide a service, even during extreme external disruptions beyond our control. • We are committed to our staff’s continued professional development. • We have an organised programme to provide young people with work experience. • We support our local community. We promise to listen • We acknowledge customer issues, and try to resolve them promptly and consistently. -

Bates' Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking

Bates’ Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking, 11th Edition Chapter 13: Male Genitalia and Hernias Multiple Choice 1. A 28-year-old musician comes to your clinic, complaining of a “spot” on his penis. He states his partner noticed it 2 days ago and it hasn't gone away. He says it doesn't hurt. He has had no burning with urination and no pain during intercourse. He has had several partners in the last year and uses condoms occasionally. His past medical history consists of nongonococcal urethritis from Chlamydia and prostatitis. He denies any surgeries. He smokes two packs of cigarettes a day, drinks a case of beer a week, and smokes marijuana and occasionally crack. He has injected IV drugs before but not in the last few years. He is single and currently unemployed. His mother has rheumatoid arthritis and he doesn't know anything about his father. On examination you see a young man appearing deconditioned but pleasant. His vital signs are unremarkable. On visualization of his penis there is a 6-mm red, oval ulcer with an indurated base just proximal to the corona. There is no prepuce because of neonatal circumcision. On palpation the ulcer is nontender. In the inguinal region there is nontender lymphadenopathy. What disorder of the penis is most likely the diagnosis? A) Condylomata acuminata B) Genital herpes C) Syphilitic chancre D) Penile carcinoma Ans: C Chapter: 13 Page and Header: 516, Table 13–2 Feedback: Primary syphilis causes a larger ulcer that is firm and painless. Syphilis is fairly uncommon but does occur in the highly promiscuous population, especially when coupled with illegal drug use. -

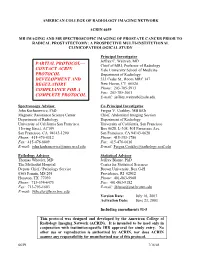

Contact Acrin Protocol Development And

AMERICAN COLLEGE OF RADIOLOGY IMAGING NETWORK ACRIN 6659 MR IMAGING AND MR SPECTROSCOPIC IMAGING OF PROSTATE CANCER PRIOR TO RADICAL PROSTATECTOMY: A PROSPECTIVE MULTI-INSTITUTIONAL CLINICOPATHOLOGICAL STUDY Principal Investigator Jeffrey C. Weinreb, MD PARTIAL PROTOCOL— Chief of MRI, Professor of Radiology CONTACT ACRIN Yale University School of Medicine PROTOCOL Department of Radiology DEVELOPMENT AND 333 Cedar St., Room MRC 147 REGULATORY New Haven, CT 06520 COMPLIANCE FOR A Phone: 203-785-5913 Fax: 203-785-3061 COMPLETE PROTOCOL E-mail: [email protected] Spectroscopy Advisor Co-Principal Investigator John Kurhanewicz, PhD Fergus V. Coakley, MB BCh Magnetic Resonance Science Center Chief, Abdominal Imaging Section Department of Radiology Department of Radiology University of California San Francisco University of California, San Francisco 1 Irving Street, AC109 Box 0628, L-308, 505 Parnassus Ave. San Francisco, CA 94143-1290 San Francisco, CA 94143-0628 Phone: 415-476-0312 Phone: 415-353-1786 Fax: 415-476-8809 Fax: 415-476-0616 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Pathology Advisor Statistical Advisor Thomas Wheeler, MD Jeffrey Blume, PhD The Methodist Hospital Center for Statistical Sciences Deputy Chief / Pathology Service Brown University, Box G-H 6565 Fannin, MS 205 Providence, RI 02912 Houston, TX 77030 Phone: 401-863-9968 Phone: 713-394-6475 Fax: 401-863-9182 Fax: 713-793-1603 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Version Date: July 16, 2003 Activation Date: June 23, 2003 Including amendments #1-5 This protocol was designed and developed by the American College of Radiology Imaging Network (ACRIN). -

There Will Be No Printed Programmes at BAUS 2018

There will be no printed programmes at BAUS 2018 Please download the BAUS 2018 App: To download the BAUS 2018 App please search ‘BAUS Annual Scientific Meeting’ on the Apple or Android app stores. Once in the portal app simply press the tile titled “BAUS 2018” to access this year’s app. IOS App Store Download Android App Store Download Web App There will be no printed programmes at BAUS 2018 Please download the BAUS 2018 App: To download the BAUS 2018 App please search ‘BAUS Annual Scientific Meeting’ on the Apple or Android app stores. Once in the portal app simply press the tile titled “BAUS 2018” to access this year’s app. IOS App Store Download Android App Store Download Web App ISSN 2051-4158 JCU Volume 11 Issue 1S June 2018 Journal of Clinical Urology Formerly British Journal of Medical and Surgical Urology An official publication of The British Association of Urological Surgeons Editor: Ian Pearce Abstracts of the BAUS 2018 Annual Scientific Meeting 25-27 June 2018 ACC Liverpool, Liverpool Volume 11 Number 1S June 2018 Contents President’s Introduction 2 Kieran O’Flynn Original Article A Series of Fortunate Events: Harold Hopkins 4 Jonathan Charles Goddard BAUS 2018 Abstracts 9 Funding statement: This work was supported by The British Association of Urological Surgeons Limited. 772797URO Journal of Clinical UrologyIntroduction Introduction Journal of Clinical Urology 2018, Vol. 11(1S) 2 –3 President’s Introduction © British Association of Urological Surgeons 2018 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/2051415818772797 10.1177/2051415818772797 journals.sagepub.com/home/uro On behalf of BAUS Council I am delighted to welcome (Cleveland, Ohio, USA) and Dr Frank van der Aa (Leuven, you to the 2018 Annual Scientific Meeting. -

The Massachusetts Register

Issue: 1151, Date: 3/5/2010 The Massachusetts Register Published by: The Secretary of the Commonwealth, William Francis Galvin, Secretary $10.00 The text of the regulations published in the electronic version of the Massachusetts Register is unofficial and for informational purposes only. The official version is the printed copy which is available from the State Bookstore at http://www.sec.state.ma.us/spr/sprcat/catidx.htm. Issue: 1151, Date: 3/5/2010 THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS Secretary of the Commonwealth - William Francis Galvin The Massachusetts Register TABLE OF CONTENTS Page - THE GENERAL COURT Acts and Resolves 1 - Division of Health Care Finance and Policy Administrative Bulletin 10-05: 114.3 CMR 47.00: Freestanding Ambulatory 3 Surgical Facilities - ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURES Notice of Public Review of Prospective Regulations 10 Cumulative Table 25 Emergency Regulations 31 Permanent Regulations 35 MASSACHUSETTS REGISTER (THE) (ISSN-08963681) is published biweekly for $300.00 per year by the Secretary fo the Commonwelath, State House, Boston, MA 02133. Second Class postage is paid at Boston, MA. POSTMASTER: Send address chagne to: Massachusetts Register, State Bookstore, Room 116, State House, Boston, MA 02133.The text of the regulations published in the electronic version of the Massachusetts Register is unofficial and for informational purposes only. The official version is the printed copy which is available from the State Bookstore at http://www.sec.state.ma.us/spr/sprcat/catidx.htm. Page Emergency Regulations 211 CMR Insurance, Division of 43.00 Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs) 31 The purpose of 211 CMR 43.00 is primarily to implement M.G.L. -

Behavioral Science and Social Sciences

ﻣﻨﺘﺪﻯ ﺍﻓﺮﻳﻘﻴﺎ ﺳﺎﺕ )) www.afriqa-sat.com ﺍﳌﻬﻨﺪﺱ : ﻋﺒﺪﺍﻟﻌﺰﻳﺰ ﺍﻟﻀﺎﻭﻱ ﻟﻠﻤﺮﺍﺳﻠﺔ ﻋﻠﻰ ﺍﻟﻔﻴﺲ ﺑﻮﻙ ﺍﻟﻀﺎﻭﻱ ﺳﺎﺕ )) www.facebook.com/aldawi.sat USMLE® Behavioral Science STEP 1 and Social Sciences Lecture Notes 2016 USMLE® is a joint program of the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) and the National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME), neither of which sponsors or endorses this product. This publication is designed to provide accurate information in regard to the subject matter covered as of its publication date, with the understanding that knowledge and best practice constantly evolve. The publisher is not engaged in rendering medical, legal, accounting, or other professional service. If medical or legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought. This publication is not intended for use in clinical practice or the delivery of medical care. To the fullest extent of the law, neither the Publisher nor the Editors assume any liability for any injury and/or damage to persons or property arising out of or related to any use of the material contained in this book. © 2016 by Kaplan, Inc. Published by Kaplan Medical, a division of Kaplan, Inc. 750 Third Avenue New York, NY 10017 Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Course ISBN: 978-1-5062-0775-9 All rights reserved. The text of this publication, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher. This book may not be duplicated or resold, pursuant to the terms of your Kaplan Enrollment Agreement. -

Understanding Icd-10-Cm and Icd-10-Pcs 3Rd Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

UNDERSTANDING ICD-10-CM AND ICD-10-PCS 3RD EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mary Jo Bowie | 9781305446410 | | | | | Understanding ICD-10-CM and ICD-10-PCS 3rd edition PDF Book Hysterectomy B-Lynch suture. Fluoroscopy Dental panoramic radiography X-ray motion analysis. Craniotomy Decompressive craniectomy Cranioplasty. Guidance on usage will follow Learn More. PCS Tables are organized in alphanumeric order in a series by Section, which is the first character of a code. Lymphadenectomy Neck dissection Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection Lymph node biopsy. Tenotomy Tendon transfer. ICD refers to the tenth edition of the International Classification of Diseases, which is a medical coding system chiefly designed by the World Health Organization WHO to catalog health conditions by categories of similar diseases under which more specific conditions are listed, thus mapping nuanced diseases to broader morbidities. View Here. Gynecological surgery. CPT remains the procedure coding standard for physicians, regardless of whether the physician services were provided in the inpatient or outpatient setting. Vasectomy Vasectomy reversal Vasovasostomy Vasoepididymostomy. Guidance on usage will follow. Thalamotomy Thalamic stimulator Pallidotomy. The letters O and I are excluded to avoid confusion with the numbers 0 and 1. WHO assumed oversight of the International Classification of Diseases ICD in with the main intention of tracking—and helping to eliminate—diseases within various populations. Tests and procedures involving the urinary system. Many countries now use national variations of ICD, each modified to align with their unique healthcare infrastructure. HZ None. Quantum computing challenges and opportunities While quantum computing is still under development, IT leaders should know how they can use it today to stay on the competitive Why are we changing from ICD-9? This will make it easier to start your search for the main term.