The Organization of Memory for Familiar Songs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1Guitar PDF Songs Index

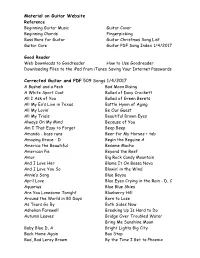

Material on Guitar Website Reference Beginning Guitar Music Guitar Cover Beginning Chords Fingerpicking Bass Runs for Guitar Guitar Christmas Song List Guitar Care Guitar PDF Song Index 1/4/2017 Good Reader Web Downloads to Goodreader How to Use Goodreader Downloading Files to the iPad from iTunes Saving Your Internet Passwords Corrected Guitar and PDF 509 Songs 1/4/2017 A Bushel and a Peck Bad Moon Rising A White Sport Coat Ballad of Davy Crockett All I Ask of You Ballad of Green Berets All My Ex’s Live in Texas Battle Hymn of Aging All My Lovin’ Be Our Guest All My Trials Beautiful Brown Eyes Always On My Mind Because of You Am I That Easy to Forget Beep Beep Amanda - bass runs Beer for My Horses + tab Amazing Grace - D Begin the Beguine A America the Beautiful Besame Mucho American Pie Beyond the Reef Amor Big Rock Candy Mountain And I Love Her Blame It On Bossa Nova And I Love You So Blowin’ in the Wind Annie’s Song Blue Bayou April Love Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain - D, C Aquarius Blue Blue Skies Are You Lonesome Tonight Blueberry Hill Around the World in 80 Days Born to Lose As Tears Go By Both Sides Now Ashokan Farewell Breaking Up Is Hard to Do Autumn Leaves Bridge Over Troubled Water Bring Me Sunshine Moon Baby Blue D, A Bright Lights Big City Back Home Again Bus Stop Bad, Bad Leroy Brown By the Time I Get to Phoenix Bye Bye Love Dream A Little Dream of Me Edelweiss Cab Driver Eight Days A Week Can’t Help Falling El Condor Pasa + tab Can’t Smile Without You Elvira D, C, A Careless Love Enjoy Yourself Charade Eres Tu Chinese Happy -

Sinatra & Basie & Amos & Andy

e-misférica 5.2: Race and its Others (December 2008) www.hemisferica.org “You Make Me Feel So Young”: Sinatra & Basie & Amos & Andy by Eric Lott | University of Virginia In 1965, Frank Sinatra turned 50. In a Las Vegas engagement early the next year at the Sands Hotel, he made much of this fact, turning the entire performance—captured in the classic recording Sinatra at the Sands (1966)—into a meditation on aging, artistry, and maturity, punctuated by such key songs as “You Make Me Feel So Young,” “The September of My Years,” and “It Was a Very Good Year” (Sinatra 1966). Not only have few commentators noticed this, they also haven’t noticed that Sinatra’s way of negotiating the reality of age depended on a series of masks—blackface mostly, but also street Italianness and other guises. Though the Count Basie band backed him on these dates, Sinatra deployed Amos ‘n’ Andy shtick (lots of it) to vivify his persona; mocking Sammy Davis Jr. even as he adopted the speech patterns and vocal mannerisms of blacking up, he maneuvered around the threat of decrepitude and remasculinized himself in recognizably Rat-Pack ways. Sinatra’s Italian accents depended on an imagined blackness both mocked and ghosted in the exemplary performances of Sinatra at the Sands. Sinatra sings superbly all across the record, rooting his performance in an aura of affection and intimacy from his very first words (“How did all these people get in my room?”). “Good evening, ladies and gentlemen, welcome to Jilly’s West,” he says, playing with a persona (habitué of the famous 52nd Street New York bar Jilly’s Saloon) that by 1965 had nearly run its course. -

A Note on the Music: May Be Helpful to Play Said Frank Sinatra Songs While Reading / Indicates an Interruption

A note on the music: May be helpful to play said Frank Sinatra songs while reading / indicates an interruption Characters: EZRA – 17. JEANNE– 21. MURPHY – 35. Setting: Pharmacy storefront. Upstage door to a mall. [Over the mall speakers play a series of Frank Sinatra songs quietly overhead. “It was a very good year” It repeats with or without lyrics until next specified change. All is calm. Bright lights. Regular business. Explosion. Panic. Running. Gun shots. Shelves pushed over. Ransacking. Small fires ignite. All lights out but one LED bulb. EZRA hobbles in, holding his bloodied leg. Kicking things with it. Painful. Looking for something, he looks at the aisle signs. Sees what he needs. He digs. Reveals a bottle of hand sanitizer. Loud sounds from outside and footsteps. Bulky men run by. EZRA is still. He looks back at the aisle signs. Sees what he needs. He digs. Reveals a sewing kit. He sits and props himself against one of the few standing shelves, rips the packaging for the sewing needles, opens the sanitizer, proceeds to tend to his wound.] EZRA: Yesterday began in a hue of grey, as all grey days do. Bits of rain and snow, but mostly just grey. Went about the daily routine. I got up. Ate my Chocolate Special K. Had coffee. Spat it out cuz I hate everything about coffee. I am trying to build up my tolerance. Brushed. Said bye to the dog. Went to school. Normal day. Slept in Ms. Grover’s. Flirted in Madame Rubin’s. Paid attention in Mr. Jatrun’s, cuz I actually learn things there. -

Washington Performing Arts Teaching Artists Enriching Experiences for Seniors (EES)

Washington Performing Arts Teaching Artists Enriching Experiences for Seniors (EES) Music Bernard Mavritte Cantaré, Latin American Music Caron Dale Chris Urquiaga Dehrric Richburg KA/PO Kelvin Page Lincoln Ross Trio Mark Hanak Not2Cool Jazz Reverb Sandra Y. Johnson Band Dance KanKouran West African Dance Ensemble Ziva’s Spanish Dance Ensemble Bernard Mavritte Bernard Mavritte was born in Washington, DC where he received his education in the public schools, and later studied Education and Vocal Studies at Howard University. He also studied Choral Conducting at the Inter-American University in Puerto Rico. He taught in DC Public Schools for many years as well as performed internationally. He also hosted a DC radio show on a leading Gospel Music station. In 1965 he toured Europe at the Assistant Musical Director for James Baldwin’s play The Amen Corner, and served as the Choral Music Director for the Tony Award winning play The Great White Hope for which one of his own compositions was used. He has performed for President John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, Barbara Streisand, Leonard Bernstein, Sammy Davis Jr, Duke Ellington, and others. He is also featured on the soundtrack of ABC television special Back to Glory where his arrangement of “The Colored Volunteers” is heard. Currently, Bernard is the CEO the publishing company Branches Music and his own record label. He has recorded five CDs and continues to perform in DC and beyond. He serves as the director and a musician for the Chancel Choir of his church, and enjoys performing regularly for Washington Performing Arts’ Enriching Experiences for seniors program. -

Not "The Thinker," but Kirke Mechem, Tennis Umpire and Som.Etimc Author and Historian

r Je :/ Not "The Thinker," but Kirke Mechem, tennis umpire and som.etimc author and historian. This recent pholograph of 1Hr. Mecbem belies a fairly general belief that the s(;holar is out of toueh with thing's oJ the world. He're he is shown calling shots at a, !.ennis tournament in Topeka. He formerly p-layed, and two of his sons gained eminenee in Kansas and Missouri Valley play, kirke mechem THE KANSAS HISTORICAL QUARTERLY Volume XVII November, 1949 Number 4 "Home on the Range" KIRKE MECHEM The night Franklin D. Roosevelt was first elected president a group of reporters sang "Home on the Range" on his doorstep in New York City. He asked them to repeat it, and made the statement, so it was said, that it was his favorite song. Later he often listened to the ballad at the White House, and it was reported that at Warm Springs he frequently led his guests in singing it. Stories of the President's approval soon made "Home on the Range" one of the country's hit songs. By 1934 it had moved to the top on the ra dio, where it stayed for six months. Everybody sang it, from Lawrence Tibbett to the smallest entertainer. Radio chains, motion picture com panies, phonograph record concerns and music publishers had a field day -all free of royalties, for there was no copyright and the author was un known. At its peak the song was literally sung around the world. Writing from Bucharest, William L. White, son of William Allen White of Kansas, said: They all know American songs, which is pleasant if you are tired of wars and little neutral capitals, and are just possibly homesick. -

Art History 101-102 (With Only a Little Fudging) Audio Bonus Answer Key 1. “Right Now”—“Before He Cheats,” Carrie Underwood (2004) 2

Art History 101-102 (With Only a Little Fudging) Audio Bonus Answer Key 1. “Right Now”—“Before He Cheats,” Carrie Underwood (2004) 2. “Some Art”—“If I Had A Million Dollars,” Barenaked Ladies (1992) 3. “History”—“Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer,” Gene Autry (1949) 4. “101”—“Honey Bun,” South Pacific (1949) 5. “102”—“Touch My Body,” Mariah Carey (2008) 6. “If I was a sculptor…”—“Your Song,” Elton John (1971) 7. “Venus de Milo” [anon., c. 100 BC]—“Venus,” Television (1977) 8. “Nike” [anon., c. 190 BC]—“Air Force Ones,” Nelly (2002) 9. “Laocoon” [anon., 25 BC]—“Laughing,” R. E. M. (1983) 10. “David” [various, including Donatello, c. 1440]—“Hallelujah,” Rufus Wainwright (2001) 11. “Cupid” [various, including Canova, 1793]—“Cupid,” Sam Cooke (1958) 12. “The Gates of Heaven” [Ghiberti, 1425]—“Bat Out of Hell,” Meat Loaf (1977) 13. “The Gates of Hell” [Rodin, late 19th c.]—“I Won’t Back Down,” Tom Petty (1989) 14. “The Walking Man” [Rodin, 1878]—“Walking Man,” James Taylor (1974) 15. “Kiss” [various, including Brancusi, 1908]—“This Kiss,” Faith Hill (1998) 16. “Fountain” [Duchamp, 1917]—“Good King Wenceslas,” Bing Crosby (1941) 17. “Architects may come and architects may go”—“So Long, Frank Lloyd Wright,” Simon & Garfunkel (1970) 18. “The Parthenon” [anon., 438 BC]—“Thanks for the Memory,” Shirley Ross & Bob Hope (1938) 19. “The Coliseum” [anon., 70]—“You’re the Top,” Ethel Merman (1936) 20. “Notre Dame” [various, including Paris 1160-1345]—“Victory March,” Notre Dame Glee Club (1905) 21. “St. Peter”[Bramante/Michelangelo, early 16th c.]—“Viva La Vida,” Coldplay (2008) 22. “The House of Lords” [Barry, 1836]—“A Day in the Life,” Beatles (1967) 23. -

Section IX the STATE PAGES

Section IX THE STATE PAGES THE FOLLOWING section presents information on all the states of the United States and the District of Columbia; the commonwealths of Puerto Rico and the Northern Mariana Islands; the territories of American Samoa, Guam and the Virgin Islands; and the United Na tions trusteeships of the Federated States of Micronesia, the Marshall Islands and the Republic of Belau.* Included are listings of various executive officials, the justices of the supreme courts and officers of the legislatures. Lists of all officials are as of late 1981 or early 1982. Comprehensive listings of state legislators and other state officials appear in other publications of The Council of State Governments. Concluding each state listing are population figures and other statistics provided by the U.S. Bureau of the Census, based on the 1980 enumerafion. Preceding the state pages are three tables. The first lists the official names of states, the state capitols with zip codes and the telephone numbers of state central switchboards. The second table presents historical data on all the states, commonwealths and territories. The third presents a compilation of selected state statistics from the state pages. *The Northern Mariana Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, the Marshall Islands and the Republic of Belau (formerly Palau) have been administered by the United Slates since July 18, 1947, as part of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (TTPl), a trusteeship of the United Nations. The Northern Mariana Islands separated themselves from TTPI in March 1976 and now operate under a constitutional govern ment instituted January 9, 1978. -

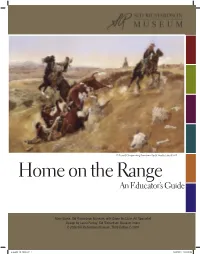

Home on the Range an Educator’S Guide

C. Russell, Cowpunching Sometimes Spells Trouble (detail) 1889 Home on the Range An Educator’s Guide Mary Burke, Sid Richardson Museum, with Diane McClure, Art Specialist Design by Laura Fenley, Sid Richardson Museum Intern © 2004 Sid Richardson Museum, Third Edition © 2009 Home09_10_2010.indd 1 9/10/2010 1:53:18 PM Home on the Range Page numbers for each section are listed below. Online version – click on the content title below to link directly to the first page of each section. For an overview of the artworks included in this booklet, see Select a Lesson – Image List, page 30. Contents Introduction to Home on the Range 4 Sid W. Richardson 6 The Museum 10 Fredric S. Remington 12 Charles M. Russell 14 Timeline (Artists, Texas, U.S. History) 16 Select a Lesson – Image List 30 Lesson Plans 32 Student Activities 52 Teacher Resources 62 2 Home on the Range Sid Richardson Museum Home09_10_2010.indd 2 9/10/2010 1:53:18 PM Sid W. Richardson Sid W. About the Educator’s Guide This Educator’s Guide is a resource for viewing and dialogue containing questions to direct classroom The Museum interpreting works of art from the Sid Richardson Museum discussion and engage students in their exploration in the classroom environment. The images included in the of the artworks, background information about Guide have been selected to serve as a point of departure the artists and the works of art, vocabulary, and for an exploration of the theme of the cowboy way of life. suggestions for extension activities • Student Activities – activities that can be used to The background materials (timelines, biographies, complement classroom discussion about these (or bibliography and resources) are appropriate for educators other) artworks The Artists of all levels. -

Download Booklet

120836bk BobHope 3/10/06 5:09 PM Page 2 1. Put It There Pal 2:23 6. My Favorite Brunette 3:06 12. Blind Date 3:12 16. Nobody 2:06 (Johnny Burke–Jimmy van Heusen) (Jay Livingston–Ray Evans) (Sid Robin) (Bert Williams–Alex Rogers From Road to Utopia From My Favorite Brunette With Margaret Whiting,The Starlighters & From The Seven Little Foys With Bing Crosby;Vic Schoen’s Orchestra With Dorothy Lamour; Billy May’s Orchestra With Veola Vonn; Orchestra conducted by Decca 40000, mx DLA 3686-A Paul Weston’s Orchestra Capitol 1042, mx 6018-1 Joe Lilley Recorded 8 December 1944, Los Angeles Capitol 381, mx 1691-3 Recorded 11 May 1950, Hollywood RCA Victor LPM 3275, mx F2PL 1443 2. Road to Morocco 2:33 Recorded 13 February 1947, Hollywood 13. Home Cookin’ 2:48 Recorded 1955, Hollywood (Johnny Burke–Jimmy van Heusen) 7. Sonny Boy 1:31 (Jay Livingston–Ray Evans) 17. I’m Tired 2:20 From Road to Morocco (Al Jolson–Buddy DeSylva–Lew Brown– From Fancy Pants (William Jerome–Jean Schwartz) With Bing Crosby;Vic Schoen’s Orchestra Ray Henderson) With Margaret Whiting,The Starlighters & From The Seven Little Foys Decca 40000, mx DLA 3687-A With The Andrews Sisters Billy May’s Orchestra Orchestra conducted by Joe Lilley Recorded 8 December 1944, Los Angeles From Radio’s Biggest Show broadcast, Capitol 1042, mx 6011-4 RCA Victor LPM 3275, mx F2PL 1443 3. The Big Broadcast of 1938: Radio 18 June 1946 Recorded 11 May 1950, Hollywood Recorded 1955, Hollywood Preview (Excerpts) introducing 8. -

Thanks for the Memories

July 2018 Volume 8, Issue 1 Thanks for the Memories To quote from the song usually connected with Bob Hope, “Thanks for the memory Of tinkling temple bells Alma mater yells And Cuban rum And towels from The very best hotels Oh how lovely it was.” (Songwriters: Leo Robin / Ralph Rainger / Thanks for the Memory lyrics © Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC) Many of us have great memories of meetings of PACE with other groups over the years. On the cusp of entering into a new era, the board has been challenged to present his or her personal memories. My first attendance was in Toronto, ON. I very well remember arriving and not having much clue of what was going on, but it didn’t take long to get into the swing of things. I also remember as a first time attendee, I received a bag of doodads, trinkets and what-nots. Hmmmm, as I recall, it took some fancy packing to get that stuffed into suitcase and carry-on for the flight home. I still have my photo from our journey to San Francisco and a trip on the California Hornblower cruise. My photo is not only me, but also Evelyn Reavis and her daughters. March of 2008 took us to Albuquerque, NM. We had a great dinner on Sandia Mountain, but didn’t get to take the tram ride due to the wind conditions. My New Orleans trip started with a six hour delay in Cincinnati, but I did arrive in time for a great Lowenstein/Sandler dinner at Antoines! Lots of fun in a great city! Austin, TX in 2016 – I remember it well. -

The Anchor Newspapers

Rhode Island College Digital Commons @ RIC The Anchor Newspapers 12-13-1967 The Anchor (1967, Volume 40 Issue 11) Rhode Island College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/the_anchor Recommended Citation Rhode Island College, "The Anchor (1967, Volume 40 Issue 11)" (1967). The Anchor. 524. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/the_anchor/524 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers at Digital Commons @ RIC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Anchor by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RIC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ESTABLISHED STMAS 1928 The ANCH 21 "FREE ACCESS TO IDEAS AND P.ULL FREEDOM OF VOL XL No. 11 RHODE ISLAND COLLEGE DECEMBER 13, 1967 Students Have Opportunity RIC·Dance Company Well Received To- Work In Washif!,gton In HighSchools Throughout TheState The Rhode island College Dance Comany completed its annual tour of several Rhode Island High Schools Friday. The host high schools included Chariho, We,;terly and East Greenwich. The ' program was varied and showed several kinds of dances beginning with the history of so cial dance - the waltz, foxtrot and cha-cha and ending with a suite of three dances choreographed .by Ed "Legs" Ortiz including the Cross fire, Skate and Sloe Gin Fizz. From a dance based on rhythm and loud music, the program ad vanced to a dance based on breath rhythm and no musical accompa niment. This was Water Study. The six dancers performing in the Senator Claiborne Pell \ shortened version of Water Study Undergraduates from the vari Program. -

Mcminnville Town Center Mcminnville, Oregon

EMBLEMS OF SACRIFICE was commissioned by the Second Winds Community Band specifically to be performed on our annual Veterans Day concert. The lyrical, dignified work was composed to honor all veterans in the region of Yamhill County Oregon and was composed by Dr. Kevin M. Walczyk, a Music professor at Western Oregon University. The composition, premiered at the November 6, 2016 performance, entitled I Remember Vietnam, serves to underscore a slide presentation comprising the images of veterans from Yamhill County (including current and former members of the Second Winds Community Band) and veterans associated with members of the band. This composition is dedicated to these local veterans - and their counterparts found in every region of the United States - who have served, and who currently serve, in our nation’s military branches as the true emblems of sacrifice. McMinnville Town Center 1321 Ne Highway 99W McMinnville, Oregon (503) 434-5813 Monday-Saturday 9:30 am - 6:00 pm Sunday 11:00 am - 4:00 pm With a broad selection of year-round and seasonal gifts, gift wrap, Keepsake Ornaments and greeting cards, Kathleen's Hallmark Shop is the perfect store for all of your special occasions. Our gift and card shop has something to help you celebrate any special occasion, holiday or even ordinary day! We wish to thank these wonderful businesses who support our band: 2019/2020 Concert Season Sunday, December 15, 2019 3:00 pm “Holiday Wonderland” Check it out at: Sunday, March 22, 2020 3:00 pm www.secondwinds.org “The Wild, Wild West” Sunday, May 17, 2020 “Pictures at an Exhibition” Contributions to SWCB are tax deductible under Summer Concerts—TBA IRS rule 501(c)3.