Episode 77 –Fever in the Returning Traveler

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Signs and Symptoms of Abdominal Diseases

General signs and symptoms of abdominal diseases Dr. Förhécz Zsolt Semmelweis University 3rd Department of Internal Medicine Faculty of Medicine, 3rd Year 2018/2019 1st Semester • For descriptive purposes, the abdomen is divided by imaginary lines crossing at the umbilicus, forming the right upper, right lower, left upper, and left lower quadrants. • Another system divides the abdomen into nine sections. Terms for three of them are commonly used: epigastric, umbilical, and hypogastric, or suprapubic Common or Concerning Symptoms • Indigestion or anorexia • Nausea, vomiting, or hematemesis • Abdominal pain • Dysphagia and/or odynophagia • Change in bowel function • Constipation or diarrhea • Jaundice “How is your appetite?” • Anorexia, nausea, vomiting in many gastrointestinal disorders; and – also in pregnancy, – diabetic ketoacidosis, – adrenal insufficiency, – hypercalcemia, – uremia, – liver disease, – emotional states, – adverse drug reactions – Induced but without nausea in anorexia/ bulimia. • Anorexia is a loss or lack of appetite. • Some patients may not actually vomit but raise esophageal or gastric contents in the absence of nausea or retching, called regurgitation. – in esophageal narrowing from stricture or cancer; also with incompetent gastroesophageal sphincter • Ask about any vomitus or regurgitated material and inspect it yourself if possible!!!! – What color is it? – What does the vomitus smell like? – How much has there been? – Ask specifically if it contains any blood and try to determine how much? • Fecal odor – in small bowel obstruction – or gastrocolic fistula • Gastric juice is clear or mucoid. Small amounts of yellowish or greenish bile are common and have no special significance. • Brownish or blackish vomitus with a “coffee- grounds” appearance suggests blood altered by gastric acid. -

Illness Reporting Log for Temporary Events and Volunteers

1020 6th Street SE Cedar Rapids, IA 52401 PH: 319-892-6000 www.linncounty.org/603/Food-Safety REPORTING OF ILLNESS FORM Worker Sign-in Sheet The purpose of this form is to inform food workers of their responsibility to notify the person in charge when they experience any of the health conditions listed below. The person in charge must take appropriate steps to prevent the transmission of foodborne illness. I AGREE TO REPORT TO THE PERSON IN CHARGE: Any onset of the following symptoms, either while at work or outside of work, including the onset date: 1. Diarrhea 2. Vomiting 3. Jaundice 4. Sore throat with fever 5. Infected cuts or wounds, or lesions containing pus on the hand, wrist , an exposed body part, or other body part and the cuts, wounds, or lesions are not properly covered (such as boils and infected wounds, however small) Medical Diagnosis: Whenever diagnosed as being ill with Norovirus, typhoid fever (Salmonella Typhi), non-typhoidal Salmonella, shigellosis (Shigella spp. infection), Escherichia coil 0157:H7 or other Enterohemorrhagic (EHEC) or Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) infection or Hepatitis A (hepatitis A virus infection) Exposure to Foodborne Pathogens: 1. Exposure to or suspicion of causing any confirmed disease outbreak of Norovirus, typhoid fever, shigellosis, E. coli 0157:H7 or other Enterohemorrhagic (EHEC) or Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) infection, or Hepatitis A. 2. A household member diagnosed with Norovirus, typhoid fever, shigellosis, E. coli 0157:H7 or other Enterohemorrhagic (EHEC) or Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) infection, or Hepatitis A. 3. A household member attending or working in a setting experiencing a confirmed disease outbreak of Norovirus, typhoid fever, shigellosis, E. -

An 8-Year-Old Boy with Fever, Splenomegaly, and Pancytopenia

An 8-Year-Old Boy With Fever, Splenomegaly, and Pancytopenia Rachel Offenbacher, MD,a,b Brad Rybinski, BS,b Tuhina Joseph, DO, MS,a,b Nora Rahmani, MD,a,b Thomas Boucher, BS,b Daniel A. Weiser, MDa,b An 8-year-old boy with no significant past medical history presented to his abstract pediatrician with 5 days of fever, diffuse abdominal pain, and pallor. The pediatrician referred the patient to the emergency department (ED), out of concern for possible malignancy. Initial vital signs indicated fever, tachypnea, and tachycardia. Physical examination was significant for marked abdominal distension, hepatosplenomegaly, and abdominal tenderness in the right upper and lower quadrants. Initial laboratory studies were notable for pancytopenia as well as an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein. aThe Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, Bronx, New York; and bAlbert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis showed massive splenomegaly. The only significant history of travel was immigration from Dr Offenbacher led the writing of the manuscript, recruited various specialists for writing the Albania 10 months before admission. The patient was admitted to a tertiary manuscript, revised all versions of the manuscript, care children’s hospital and was evaluated by hematology–oncology, and was involved in the care of the patient; infectious disease, genetics, and rheumatology subspecialty teams. Our Mr Rybinski contributed to the writing of the multidisciplinary panel of experts will discuss the evaluation of pancytopenia manuscript and critically revised the manuscript; Dr Joseph contributed to the writing of the manuscript, with apparent multiorgan involvement and the diagnosis and appropriate cared for the patient, and was critically revised all management of a rare disease. -

Atypical Abdominal Pain in a Patient with Liver Cirrhosis

IMAGE IN HEPATOLOGY January-February, Vol. 17 No. 1, 2018: 162-164 The Official Journal of the Mexican Association of Hepatology, the Latin-American Association for Study of the Liver and the Canadian Association for the Study of the Liver Atypical Abdominal Pain in a Patient With Liver Cirrhosis Liz Toapanta-Yanchapaxi,* Eid-Lidt Guering,** Ignacio García-Juárez* * Gastroenterology Department. National Institute of Medical Science and Nutrition “Salvador Zubirán”. Mexico City. Mexico. ** Interventional Cardiology. National Institute of Cardiology “Ignacio Chávez”. Mexico City. Mexico. ABSTRACTABSTABSTABSTRACT The causes of abdominal pain in patients with liver cirrhosis and ascites are well-known but occasionally, atypical causes arise. We report the case of a patient with a ruptured, confined abdominal aortic aneurysm. KeyK words.o d .K .Key Liver cirrhosis. Abdominal aortic aneurysm. INTRODUCTION CASE REPORT Abdominal pain in cirrhotic patients is a challenge. A 47-year-old male with the established diagnosis of Clinical presentation can be non-specific and the need for alcohol-related liver cirrhosis, presented to the emer- early surgical exploration may be difficult to assess. Coag- gency department for abdominal pain. He was classified ulopathy, thrombocytopenia, varices, and ascites need to as Child Pugh (CP) C stage (10 points) and had a model be taken into account, since they can increase the surgical for end stage liver disease (MELD) - sodium (Na) of 21 risk. Possible differential diagnoses include: Complicated points. The pain was referred to the left iliac fossa, with umbilical, inguinal or postoperative incisional hernias, an intensity of 10/10. It was associated to low back pain acute cholecystitis, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, pep- with radicular stigmata (primarily S1). -

High Risk Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy Tubes: Issues to Consider

NUTRITIONINFLAMMATORY ISSUES BOWEL IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, DISEASE: A PRACTICAL SERIES APPROACH, #105 SERIES #73 Carol Rees Parrish, M.S., R.D., Series Editor High Risk Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy Tubes: Issues to Consider Iris Vance Neeral Shah Percutaneous endoscopy gastrostomy (PEG) tubes are a valuable tool for providing long- term enteral nutrition or gastric decompression; certain circumstances that complicate PEG placement warrant novel approaches and merit review and discussion. Ascites and portal hypertension with varices have been associated with poorer outcomes. Bleeding is one of the most common serious complications affecting approximately 2.5% of all procedures. This article will review what evidence exists in these high risk scenarios and attempt to provide more clarity when considering these challenging clinical circumstances. INTRODUCTION ince the first Percutaneous Endoscopic has been found by multiple authors to portend a poor Gastrostomy tube was placed in 1979 (1), they prognosis in PEG placement (3,4, 5,6,7,8). This review Shave become an invaluable tool for providing will endeavor to provide more clarity when considering long-term enteral nutrition (EN) and are commonly used these challenging clinical circumstances. in patients with dysphagia following stroke, disabling motor neuron diseases such as multiple sclerosis and Ascites & Gastric Varices amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and in those with head The presence of ascites is frequently viewed as a and neck cancer.They are also used for patients with relative, if not absolute, contraindication to PEG prolonged mechanical intubation, as well as gastric placement. Ascites adds technical difficulties and the decompression in those with severe gastroparesis, risk for potential complications (see Table 1). -

Successful Conservative Treatment of Pneumatosis Intestinalis and Portomesenteric Venous Gas in a Patient with Septic Shock

SUCCESSFUL CONSERVATIVE TREATMENT OF PNEUMATOSIS INTESTINALIS AND PORTOMESENTERIC VENOUS GAS IN A PATIENT WITH SEPTIC SHOCK Chen-Te Chou,1,3 Wei-Wen Su,2 and Ran-Chou Chen3,4 1Department of Radiology, Changhua Christian Hospital, Er-Lin branch, 2Department of Gastroenterology, Changhua Christian Hospital, 3Department of Biomedical Imaging and Radiological Science, National Yang-Ming University, and 4Department of Radiology, Taipei City Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan. Pneumatosis intestinalis (PI) and portomesenteric venous gas (PMVG) are alarming radiological findings that signify bowel ischemia. The management of PI and PMVG remain a challenging task because clinicians must balance the potential morbidity associated with unnecessary sur- gery with inevitable mortality if the necrotic bowel is not resected. The combination of PI, portal venous gas, and acidosis typically indicates bowel ischemia and, inevitably, necrosis. We report a patient with PI and PMVG caused by septic shock who completely recovered after conservative treatment. Key Words: bowel ischemia, computed tomography, pneumatosis intestinalis, portal venous gas, portomesenteric venous gas (Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2010;26:105–8) Pneumatosis intestinalis (PI) and portomesenteric CASE PRESENTATION venous gas (PMVG) are alarming radiologic findings that signify bowel ischemia [1]. PI and PMVG are A 78-year-old woman who presented with intermittent often described as an advanced sign of bowel injury, fever for 3 days was referred to the emergency depart- indicating irreversible injury caused by transmural ment of our hospital. The patient had a history of ischemia [2]. Bowel ischemia may be associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, and perforation and has a high mortality rate. Many au- prior cerebral infarct. -

Case Report Gastric Volvulus Due to Splenomegaly - a Rare Entity

Case Report Gastric Volvulus Due to Splenomegaly - A rare Entity. Ashok Mhaske Department of Surgery,People’s College of Medical Sciences and Research Centre, Bhanpur, Bhopal. 462010 , (M.P.) Abstract: Gastric volvulus is a rare condition which typically presents with intermittent episodes of abdominal pain. The volvulus occurs around an axis made by two fixed points, organo-axial or mesentero-axial. Increased pressure within the hernial sac associated with gastric distension can lead to ischemia and perforation. Acute obstruction of a gastric volvulus is thus a surgical emergency.We present an unusual case of gastric volvulus secondary to tropical splenomegaly. Tropical splenomegaly precipitating gastric volvulus is not documented till date. Key Words: Gastric volvulus, Tropical splenomegaly. Introduction: to general practitioner but as symptoms persisted she Gastric volvulus is abnormal rotation of the was referred to our tertiary care centre for expert stomach of more than 180 degrees. It can cause closed opinion and management. loop obstrcution and at times can result in On examination, vital parameters and hydration was adequate with marked tenderness in incarceration and strangulation. Berti first described epigastric region with vague lump. Her routine gastric volvulus in 1866; to date, it remains a rare investigations were inconclusive but she did partially clinical entity. Berg performed the first successful responded to antispasmodic and antacid drugs. operation on a patient with gastric volvulus in 1896. Ultrasound of abdomen and Barium studies Borchardt (1904) described the classic triad of severe revealed gastric volvulus (Fig.1 & 2) with epigastric pain, retching without vomiting and splenomegaly for which she was taken up for inability to pass a nasogastric tube. -

Water Borne Diseases in the Pacific Region

ExamplesExamples ofof DiseasesDiseases AAssociatedssociated withwith WaterborneWaterborne TransmissionTransmission inin thethe PacificPacific IslandIsland RegionRegion Second Seminar on Water Management in Islands Coastal and Isolated Areas Noumea, New Caledonia, 26-28 May 2008 François FAO Public Health Surveillance and Communicable Disease Control Section Secretariat of the Pacific Community OutbreaksOutbreaks ofof communicablecommunicable diseasesdiseases withwith waterwater playingplaying aa potentialpotential oror majormajor rolerole inin thethe transmissiontransmission CholeraCholera TyphoidTyphoid feverfever LeptospirosisLeptospirosis MinistersMinisters ofof HealthHealth CommitmentCommitment ¾¾ YanucaYanuca (1995):(1995): ConceptConcept ofof ““healthyhealthy islandsislands”” == ecologicalecological modelmodel ofof healthhealth promotion.promotion. ““ HealthyHealthy islandsislands shouldshould bebe placesplaces where:where: z ChildrenChildren areare nurturednurtured inin bodybody andand mindmind z EnvironmentsEnvironments inviteinvite learninglearning andand leisureleisure z PeoplePeople workwork andand ageage withwith dignitydignity z EcologicalEcological balancebalance isis sourcesource ofof pridepride”” WhatWhat isis thethe PPHSN?PPHSN? ¾ PPHSNPPHSN isis aa voluntaryvoluntary networknetwork ofof countries/territoriescountries/territories andand institutions/institutions/ organisationsorganisations ¾ DedicatedDedicated toto thethe promotionpromotion ofof publicpublic healthhealth surveillancesurveillance && responseresponse ¾ -

Typhoid Fever

Osteopathic Family Physician (2014)4, 23-27 23 REVIEW ARTICLE Typhoid Fever Patricio Bruno, DO1; Joseph Podolski, DO2; Mona Doss, MSIV3; Mike DeWall, OMSIII4 1Director of Medical Education and Program Director, Family Medicine Residency, Florida Hospital East Orlando; 2Director of Medical Education and Program Director, Osteopathic Internship, Eastern CT Health Network 3Connecticut Children’s Medical Center at the University of Connecticut; 4The Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine KEYWORDS: A 26-year-old presented to the ER with symptoms of unknown infection. Upon admission and hospitalization, the patient’s vitals, labs, and hemodynamic function decreased; therefore, he was Typhoid fever placed in the ICU for further management. After blood cultures came back positive for Salmonella Salmonella typhi typhi, the patient was started on strong antibiotics and eventually stabilized and was released Enteric fever home. This case represents an atypical presentation and the further management of Salmonella Salmonella paratyphi typhi infection in the primary care setting. The patient presented to the emergency room as a recent traveler to America from India, where Salmonella typhi is considered endemic. A few hours from initial presentation, the patient deteriorated and was admitted to the ICU, where further workup was done, including imaging, cultures, and labs. After blood cultures came up positive for non-lactose fermenting gram-negative rods, later identified to be the Salmonella typhi organism, the patient was put on tobramycin and levofloxacin for 10 days; he eventually stabilized and was discharged home. Primary care physicians see everything from standard follow-up for hypertension to acute and/or chronic exacerbations of heart failure. -

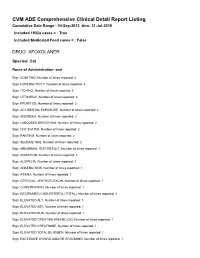

FDA CVM Comprehensive ADE Report Listing for Afoxolaner

CVM ADE Comprehensive Clinical Detail Report Listing Cumulative Date Range : 04-Sep-2013 -thru- 31-Jul-2018 Included 1932a cases = : True Included Medicated Feed cases = : False DRUG: AFOXOLANER Species: Cat Route of Administration: oral Sign: VOMITING, Number of times reported: 4 Sign: HYPERACTIVITY, Number of times reported: 3 Sign: ITCHING, Number of times reported: 3 Sign: LETHARGY, Number of times reported: 3 Sign: PRURITUS, Number of times reported: 3 Sign: ACCIDENTAL EXPOSURE, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: ANOREXIA, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: LABOURED BREATHING, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: NOT EATING, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: PANTING, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: SEIZURE NOS, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: ABNORMAL TEST RESULT, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: AGITATION, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ALOPECIA, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ANAEMIA NOS, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ATAXIA, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: CERVICAL VENTROFLEXION, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: CONSTIPATION, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: DECREASED CHOLESTEROL (TOTAL), Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED ALT, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED AST, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED BUN, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED CREATINE-KINASE (CK), Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED CREATININE, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED TOTAL BILIRUBIN, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: EXCESSIVE LICKING AND/OR GROOMING, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: FEVER, -

Enteric Infections Due to Campylobacter, Yersinia, Salmonella, and Shigella*

Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 58 (4): 519-537 (1980) Enteric infections due to Campylobacter, Yersinia, Salmonella, and Shigella* WHO SCIENTIFIC WORKING GROUP1 This report reviews the available information on the clinical features, pathogenesis, bacteriology, and epidemiology ofCampylobacter jejuni and Yersinia enterocolitica, both of which have recently been recognized as important causes of enteric infection. In the fields of salmonellosis and shigellosis, important new epidemiological and relatedfindings that have implications for the control of these infections are described. Priority research activities in each ofthese areas are outlined. Of the organisms discussed in this article, Campylobacter jejuni and Yersinia entero- colitica have only recently been recognized as important causes of enteric infection, and accordingly the available knowledge on these pathogens is reviewed in full. In the better- known fields of salmonellosis (including typhoid fever) and shigellosis, the review is limited to new and important information that has implications for their control.! REVIEW OF RECENT KNOWLEDGE Campylobacterjejuni In the last few years, C.jejuni (previously called 'related vibrios') has emerged as an important cause of acute diarrhoeal disease. Although this organism was suspected of being a cause ofacute enteritis in man as early as 1954, it was not until 1972, in Belgium, that it was first shown to be a relatively common cause of diarrhoea. Since then, workers in Australia, Canada, Netherlands, Sweden, United Kingdom, and the United States of America have reported its isolation from 5-14% of diarrhoea cases and less than 1 % of asymptomatic persons. Most of the information given below is based on conclusions drawn from these studies in developed countries. -

Bacterial Foodborne and Diarrheal Disease National Case Surveillance

Bacterial Foodborne and Diarrheal Disease National Case Surveillance Annual Report, 2003 Enteric Diseases Epidemiology Branch Division of Foodborne, Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases National Center for Zoonotic, Vectorborne and Enteric Diseases Centers for Disease Control and Prevention The Bacterial Foodborne and Diarrheal Disease National Case Surveillance is published by the Enteric Diseases Epidemiology Branch, Division of Foodborne, Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases, National Center for Zoonotic, Vectorborne and Enteric Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA 30333 SUGGESTED CITATION Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Bacterial Foodborne and Diarrheal Disease National Case Surveillance. Annual Report, 2003. Atlanta Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2005: pg. Nos - 2 - Contents Executive Summary……………………………………………………………………………… - 4- Expanded Surveillance Summaries of Selected Pathogens and Diseases, 2003………………… -10- Botulism…………………………………………………………………………………. -10- Non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli………………………………………-18- Salmonella………………………………………………………………………………...-22- Shigella……………………………………………………………………………………-28- Vibrio……………………………………………………………………………………...-33- Surveillance Data Sources and Background……………………………………………………... -40- National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System and the National Electronic Telecommunications System for Surveillance…………………………………………… -40- Public Health Laboratory Information System…………………………………………... -41- Limitations common to NETSS and PHLIS……………………………………………..