EXECUTIVE SUMMARY State of the Somerset Economy 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Triscombe House Quantock Hills, Somerset

Triscombe House Quantock Hills, Somerset Triscombe House Quantock Hills, Somerset A majestic Grade II listed country house in an accessible location and magical parkland setting with far reaching views over the Blackdown Hills to the south and the Quantock Hills to the north. Biomass heating and solar PV systems have been installed that generate an income to cover running costs. The property also has a Lodge which can further enhance this income through rental. Bishop’s Lydeard 4.4 miles, Taunton 9.4 miles (London Paddington 1 hour 40 minutes), Bristol Airport 40 miles, Exeter 40 miles (All mileages are approximate) Ground floor: Reception hall | Drawing room | Library | Dining room | Family sitting room| Winter garden room Kitchen / breakfast room| Pantry | Study | Home office| Coat / boot room | Flower room | Link to boiler house. Lift to all floors Lower ground floor: Home cinema | Store room | Cloakroom | Lobby | Wine cellar First floor: Master bedroom with dressing room and en suite bathroom| Two guest bedrooms with en suite bathrooms Four further bedrooms | Family bathroom | Laundry room | Linen room Second floor: Guest bedroom with en suite bathroom | Bedroom with dressing room | Two further bedrooms | Bathroom | Playroom Soundproof recording studio| Studio room / home office| Sitting room / bedroom 11| Three storage rooms The Lodge: Kitchen | Sitting room| Utility room | 3 bedrooms | Bathroom | Garden Outbuildings: Attached outbuilding with storage and cloakroom on ground floor and home office above Stable block with four loose -

Great Wood Volcano Walk, Quantock Hills, Somerset

A) Campbell Room to Seven Wells car park Route 1 Great Wood Volcano Walk From the Campbell Room ❶, turn left and walk along the road towards Great Wood forest. The stream on your right, raised above road level, is actually a leet built to supply Distance: 3.5miles (5.5km) Height gain: 680 feet (207m) Time: 1.5 to 2 hours water to the former flour and silk mills at Marsh Mills. After Adscombe Farm the road Map: Ordnance Survey Explorer Map 140 Quantock Hills & Bridgwater. rises, becoming a forest track at the cattle grid ❷. You could continue directly ahead along the track, but take the right hand track up hill instead. Just after the car barrier, Parking: Seven Wells car park (ST173373), marked ❺ on the sketch below. turn left off the track ❸ and take the narrow bridleway between the trees. This brings Start and finish: The Campbell Room or Seven Wells car park. you back to the main track to Seven Wells just before the entrance to Greatwood Camp. Continue along the track for just over half a mile to reach the Seven Wells car park or — This easy circular walk in the Quantock Hills follows tracks and bridleways if you started from the Campbell Room — you could save half a mile by cutting down through Great Wood forest, fields and open parkland, as well as taking you the small path a few hundred metres on the left after Greatwood Camp ❹, crossing the over rock from the Quantock's very own extinct volcano. The sections on local stream and turning left onto the track on the other side of the valley floor. -

Quantock and Blackdown Hills

Spring 2018 Quantock and Blackdown hills Looking after Fyne Court and Wellington Monument as well as over 600 hectares of designated Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. Together, we can look after this special place for ever, for everyone . Our work Wildlife spotting What’s on? Looking after places Cadbury Easter egg hunt Friday 30 March to Monday 2 April, 10am-2pm, Fyne people live Court Head to Fyne Court’s wild garden in search for spring- time clues to earn your reward Somerset Festival of Nature Saturday 5 May, Fyne Court, Quantock Hills Kick off a month of celebration of nature across all of Somerset Top of the Gorge festival Friday 22 June to Sunday 24 June, Cheddar Gorge Enjoy a weekend of adventure sports Stay a little longer… Where next? A former gardener’s cottage bursting with character, Coleridge Cottage Fyne Court Cottage, sleeps 6. Home of romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge and the start of the Coleridge Way walk Search availability at nationaltrust.org.uk/holidays Knightshayes A country estate on a grand gothic scale, surrounded by acres of glorious gardens and parkland Barrington Court An empty Tudor house beautifully restored in the 1920s Fyne Court waymarked wander Fyne Court was home to the Crosse family for generations, until the house was destroyed by fire in 1894. The estate’s garden is now a haven for wildlife. Explore this wild garden, now hidden away in the Quantock Hills. Whether you’re looking for wildlife, natural play or peace and tranquillity, Fyne Court’s waymarked trails offer a lot to discover. -

Somerset Geology-A Good Rock Guide

SOMERSET GEOLOGY-A GOOD ROCK GUIDE Hugh Prudden The great unconformity figured by De la Beche WELCOME TO SOMERSET Welcome to green fields, wild flower meadows, farm cider, Cheddar cheese, picturesque villages, wild moorland, peat moors, a spectacular coastline, quiet country lanes…… To which we can add a wealth of geological features. The gorge and caves at Cheddar are well-known. Further east near Frome there are Silurian volcanics, Carboniferous Limestone outcrops, Variscan thrust tectonics, Permo-Triassic conglomerates, sediment-filled fissures, a classic unconformity, Jurassic clays and limestones, Cretaceous Greensand and Chalk topped with Tertiary remnants including sarsen stones-a veritable geological park! Elsewhere in Mendip are reminders of coal and lead mining both in the field and museums. Today the Mendips are a major source of aggregates. The Mesozoic formations curve in an arc through southwest and southeast Somerset creating vales and escarpments that define the landscape and clearly have influenced the patterns of soils, land use and settlement as at Porlock. The church building stones mark the outcrops. Wilder country can be found in the Quantocks, Brendon Hills and Exmoor which are underlain by rocks of Devonian age and within which lie sunken blocks (half-grabens) containing Permo-Triassic sediments. The coastline contains exposures of Devonian sediments and tectonics west of Minehead adjoining the classic exposures of Mesozoic sediments and structural features which extend eastward to the Parrett estuary. The predominance of wave energy from the west and the large tidal range of the Bristol Channel has resulted in rapid cliff erosion and longshore drift to the east where there is a full suite of accretionary landforms: sandy beaches, storm ridges, salt marsh, and sand dunes popular with summer visitors. -

A Guide to Living in Wellington, Somerset by Helen Heyns at Love Lifestyle

A guide to living in Wellington, Somerset By Helen Heyns at Love Lifestyle Wellington Monument Create your dream lifestyle in Somerset. Information for those interested in moving to Wellington. www.lovelifestyle.org Somerset countryside, by Craig Stone A friendly market town. Wellington is a small market town in rural Somerset, a county in the South West of England, near the border with Devon, which runs between the Blackdown Hills and the Brendon Hills with the County town of Taunton to the north. Boasting an abundance of boutique, independent stores there are plenty of options for eating out, watching the world go by, or gathering high quality ingredients for a more DIY experience. Wellington has a a population of 14,549; it is home to a public school, Wellington School, founded in 1837, and a 1930s cinema, The Wellesley. Wellington Cricket Club have a ground off Courtland Road, and have two teams in the Somerset Cricket League. Take a wander through the high street, and admire the historic buildings, such as Wellington Museum where you can learn about the Fox family, and Visit Wellington Monument, a 175ft column built to honour 'Iron Duke', victor of the Battle of Waterloo. Welcoming you with open arms, as they live and work amongst the beauty that they call home, the community within Wellington. Make the most of your surroundings and explore the area, with many National Trust locations, beaches, castles, and museums. Take a look at Visit Somerset for information. Here is our Guide to Wellington, and the surrounding area… www.lovelifestyle.org Restaurants, cafes & Coffee Shops Wellington is known as a 'food town' with food to appeal to all tastes. -

FROM: the South West AONB Family: Blackdown Hills, Cornwall

FROM: The South West AONB Family: Blackdown Hills, Cornwall, Cotswolds, Cranborne Chase, Dorset, East Devon, Mendip Hills, North Devon, North Wessex Downs, Quantock Hills, South Devon, Tamar Valley Dear Colleague The Colchester Declaration : A commitment to nature’s recovery by the Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONBs) Launched in 2019, the Colchester Declaration is an ambitious plan, led by the Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONBs), to recover nature in and beyond protected landscapes, build climate resilience and enhance engagement with people. The Colchester Declaration frames our urgent initial response to the climate and ecological emergency recognised by authorities throughout the UK. While clearly requiring some planning, it is focussed on delivering action for habitats and biodiversity at a significant scale in the shortest possible time. Realising this ambition will require additional resources, forging new partnerships and cementing strong alliances with partners: a task we have been focussing on over the past few months. This builds on successful nature recovery solutions delivered through AONB partnerships 70@70 and will help deliver the goals in the Landscapes Review and the 25 Year Environment Plan (YEP). In the south west, we are plugging into county Nature Recovery Network processes and engaging though Local Nature Partnerships to both embed the approaches outlined in the Colchester Declaration and secure buy-in, but also to ensure alignment and added value. There are two key areas of progress we would like to share with you. Firstly, we have produced a framework for Nature Recovery Plans (NRPs), a key commitment in the Colchester Declaration and each of the 38 AONBs in England and Wales will be co- creating an iterative plan. -

21Landscape and Visual Impact

21. Landscape and Visual Impact 21 LANDSCAPE AND VISUAL IMPACT 21.1 Introduction 21.1.1 This chapter provides an assessment of the Hinkley Point C Development on the local and wider landscape and on a range of identified sensitive visual receptors. The assessment has been undertaken through a combination of review of available information on landscape character and sensitivities, consultation with appropriate organisations, the use of 3d modelling techniques and the establishment of a number of viewpoints around the proposed Hinkley Point C Development Site from which potential visual impact may be apparent. 21.1.2 The assessment has been undertaken through a staged approach which is reflected in the structure of this chapter. The landscape and visual policy context for the scheme is set out in section three and is followed in section four by a description of the assessment methodology. 21.1.3 The fifth section consists of a baseline study of the landscape and visual resource of the existing site and its surroundings. This breaks the landscape down into component parts, which assists with identifying any elements or features that might be particularly sensitive to the proposed development. 21.1.4 The sixth section sets out the potential landscape and visual impacts that the scheme could have without any mitigation, including construction phase landscape and visual effects and potential effects on the completion of the scheme. Mitigation measures are described in section seven and the significance of any residual effects are described in section eight. 21.1.5 In parallel with EDF Energy’s consultation process, National Grid is consulting on its proposals to provide a new high voltage overhead line between Bridgwater and Seabank near Avonmouth, together with more upgrades and modifications to existing overhead lines in the vicinity of Hinkley Point. -

Annual Review Annual Review 2019-2020

Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Photo: Liam Marsh ANNUAL REVIEW 2019-2020 Foreword This was my last full year with the Blackdown partners to formulate a nature recovery plan for Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty the Blackdown Hills. (AONB), saying farewell to a wonderful group The Discovering Dunkeswell Abbey Project ran of dear friends with whom I have shared many in partnership with Heritage, Arts and People. happy times. The qualities of the Blackdown This enabled local people young and old to Hills outstanding landscape were always clear learn about this little-known 13th century to me but what I hadn’t initially appreciated was Cistercian Abbey located between Dunkeswell the tremendous feeling that local people had for and Hemyock. where they lived. Arriving in Stockland’s Kings Arms Inn in 1987, I was immediately involved Via the Somerset Nature and Wellbeing project, in the AONB and remained so since then but, we continued to support members of the local after several health setbacks, I felt the time was community who might not ordinarily access the right to complete my withdrawal from such an countryside to experience the Blackdown Hills. active public life. Our volunteer co-ordinator, who works across Blackdown Hills AONB has continued to spread both the Quantock Hills and Blackdown Hills its wings, no more so than with the Connecting AONBs, continued to recruit volunteers for the Culm project. The project is exploring ways activities such as biological surveys and in which the River Culm and its catchment can practical conservation. adapt to the impact of climate change using nature-based interventions and working with I will miss being a part of the Blackdown Hills local communities along the full length of the AONB partnership management group but plan River to co-design a blueprint for its future. -

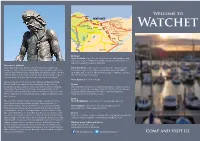

WATCHET DUNSTER T Railway Kilve A39 A39

Porlock Welcome to MINEHEAD We st Somerse WATCHET DUNSTER t Railway Kilve A39 A39 Nether Stowey EXMOOR Williton Wheddon Bicknoller Cross NATIONAL PARK Roadwater W A39 Luxborough est Somerset Crowcombe BRIDGWATER Watchet Monksilver A396 A358 R a QUANTOCK HILLS il BRENDON HILLS w a y West Bagborough Bishops Lydeard Kingston DULVERTON Upton St-Mary A358 Norton TAUNTON Fritzwarren A38 WELLINGTON A396 By Road From the East: Leave the M5 at Junction 23 (Bridgwater) and follow the signs for Minehead (A39). After about 16 miles turn right following the signs to Watchet. Welcome to Watchet Come and watch the boats, walk the beaches, explore the From the West: Leave the M5 at Junction 25 (Taunton) and rockpools, take a steam railway trip, linger round the galleries, follow the signs to the A358 towards Minehead. At Williton listen to the fiddle players, drink cider, sample the cafes, see the turn right and then left following the signs to Watchet (about carnival, dance at the music festival, take a fishing trip, explore 18 miles from the motorway). the museums, find gifts in the local shops and a lot more! From Exeter: Follow the A396. Watchet heralds from a time when Vikings raided and King Canute had coins cast from his royal mint. Kings, queens, By Rail murderous knights, pirates, saints and even a famous singing National Rail connection to either Bridgwater or Taunton then sailor have their stories to tell here. The wild beauty of its by bus. Local steam and diesel trains to Watchet from Bishops coastline is untouched and ancient ammonite fossils lie on the Lydeard and Minehead on The West Somerset Railway - shore, waiting to be found along long, empty, windswept, rock www.west-somerset-railway.co.uk. -

Taunton Deane Landscape Character Assessment – Report 1 Taunton Deane Landscape Character Assessment

Taunton Deane Landscape Character Assessment – Report 1 Taunton Deane Landscape Character Assessment Introduction....................................................................................................................................... 3 Background and Context ...................................................................................................3 Landscape Character Assessment ................................................................................................. 8 Landscape Type 1: Farmed and Settled Low Vale....................................................................... 25 Character Area 1A: Vale of Taunton Deane ....................................................................25 Landscape Type 2: River Floodplain ............................................................................................ 37 Character Area 2A: The Tone..........................................................................................37 Landscape Type 3: Farmed and Settled High Vale...................................................................... 45 Character Area 3A: Quantock Fringes and West Vale.....................................................46 Character Area 3B: Blackdown Fringes ...........................................................................47 Landscape Type 4: Farmed and Wooded Lias Vale .................................................................... 55 Character Area 4A: Fivehead Vale ..................................................................................55 -

Highgrove, 18D St Decumans Road, Watchet, Somerset, Ta23 0At Heigard Property Developments

H 18D ST DECUMANSighgrove ROAD, WATCHET, TA23 0AT HEIGARD DELIVERS HOUSE, HOME AND INSPIRATION Focusing on quality, attention to detail and functionality to create living spaces which offer a combination of the practical and the best of the future of design. HIGHGROVE, 18D ST DECUMANS ROAD, WATCHET, SOMERSET, TA23 0AT HEIGARD PROPERTY DEVELOPMENTS WATCHET Watchet is an ancient harbour town boasting a colourful maritime history dating back over two thousand years. It was an important Saxon port and the site of a Royal Mint, coins from which have been found as far as Copenhagen and Stockholm as a result of Viking raids. 21st Century Watchet still holds all the charm from long ago while offering the amenities essential to modern living. The town certainly has a great deal to offer anyone wishing to make their home here. The coastline and Watchet Harbour Marina are notable attractions of the area. In 2001 a new commercial marina was built, dividing the harbour into outer and inner areas. The marina has a capacity for 250 yachts and adds to Watchet’s unique charm. Nestled between Exmoor National Park and the Quantock Hills it is hard to believe that the M5 is only half an hour away, with Bristol and its international airport easily commutable. Exmoor National Park has a unique landscape of moorland, woodland, valleys and farmland. High cliffs plunge into the Bristol Channel, and cosy pubs and tearooms offer delicious local produce. Catch a glimpse of wild red deer, be amazed by dark skies full of stars, and explore villages full of character. -

Coleridge and Wordsworth in the Quantocks

Coleridge and Wordsworth in the Quantocks Written and designed by Terence Sackett of the Friends of Coleridge Why did the two poets choose the Quantocks? Samuel Taylor Coleridge first visited Nether Stowey in 1794, while on a walking A fine country house for the Wordsworths tour of Somerset with the poet Robert Southey. Crossing the River Parrett at Coleridge first met William Wordsworth in Combwich, they visited Coleridge’s Cambridge friend Henry Poole at Shurton. Bristol. The two poets took to each other Henry Poole took them to Nether Stowey where Coleridge was introduced to immediately. the man who was to be his most faithful friend and supporter – the tanner and In 1797 Wordsworth and his sister Dorothy Stowey benefactor Thomas Poole. were renting a country house at Racedown Poole accompanied them on a visit to the home of his conventional cousins at in West Dorset. Coleridge, keen to renew nearby Marshmills. The poets shocked them with their radical republican views and deepen the friendship, rushed down to and support for the French Revolution – England was at war with France at the persuade them to move to the Quantocks. Thomas Poole time and there was a serious threat of a French invasion. They found his enthusiasm impossible to resist. Once again Tom Poole was given the task CHRISTIE’S A poor choice of cottage of finding a house for the Wordsworths to Alfoxden House, near Holford to rent. Alfoxden, just outside the village of In 1796 Samuel Taylor Coleridge was living in Bristol. ‘There is everything here, sea, woods wild as fancy Holford and four miles from Stowey, could In his characteristically courageous and foolhardy ever painted, brooks clear and pebbly as in not have been more different to Gilbards.