Discordant Patterns of Nuclear and Mitochondrial Introgression in Iberian Populations of the European Common Frog (Rana Temporaria)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Texto Completo

3 Articulo 13 17/4/01 19:30 Página 231 231 PROPOSTA DIDÁCTICA: EXCURSIÓN GUIADA ÓS ANCARES JosŽ Carlos Otero L—pez Enrique Carrera Soto Colexio Lar Pontevedra 1. FUNDAMENTACIÓN terra, creando as’ un forte lazo entre o individuo e a paisaxe. A educaci—n libresca destru’u este lazo na inmensa A educaci—n ambiental Ž un dos maior’a da poboaci—n escolar do noso piares fundamentais da Reforma pa’s. A educaci—n ambiental retoma para Educativa e a conservaci—n da natureza si o papel de creadora de cidad‡ns co–e- conforma unha das ‡reas transversais cedores das posibilidades e l’mites do fundamentais no contexto da educaci—n seu medio ambiente, de mentalidade primaria e secundaria. O aproveitamen- conservacionista, logo de varias xera- to pedag—xico da natureza como elemen- ci—ns de mentalidade explotadora. to de imprescindible valoraci—n considŽ- rase nun dobre aspecto: por un lado, o Ante esta premisa, propo–emos encontro coa natureza perm’tenos descu- nas seguintes li–as unha experiencia bri-la importancia que ten de seu e o pr‡ctica e sinxela que se pode aplicar en perigo permanente da sœa destrucci—n, e calquera centro educativo da nosa comu- por outro lado o feito de que a natureza nidade Ñindependentemente do nivelÑ nos axuda a enfrontarnos coa nosa pro- e queremos facer notar ademais que esta pia realidade como persoas. Estes ele- experiencia non ten por quŽ reducirse mentos contribœen a favorecer compor- exclusivamente — alumnado, sen—n que tamentos actitudinais positivos no tamŽn Ž posible a presencia de pais e individuo que participa en actividades nais, co que entramos no ‡mbito da edu- desenvolvidas no medio natural. -

The Geomorphological Role of Snow Since the Little Ice Age in the Sierra De Ancares (Nw Spain)

Cuadernos de Investigación Geográfica ISSN 0211-6820 2018 Nº 44 (1) pp. 171-185 Geographical Research Letters eISSN 1697-9540 DOI: http://doi.org/10.18172/cig.3379 THE GEOMORPHOLOGICAL ROLE OF SNOW SINCE THE LITTLE ICE AGE IN THE SIERRA DE ANCARES (NW SPAIN) P. CARRERA-GÓMEZ, M. VALCÁRCEL* Departamento de Xeografía, Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, Praza da Universidade, 1, 15782-Santiago de Compostela (A Coruña), Spain. ABSTRACT. On the Pico Cuiña cirque, Sierra de Ancares (León, Spain), the seasonal snow cover undergoes both slow and rapid mass displacements. Push associated with moving snow is responsible for an intense geomorphological activity, which is characterised by the plucking and transport of fragments of the bedrock, the abrasion of rock surfaces and the deposition of the mobilized material. Pronival ramparts are the most characteristic accumulation geoform created by pushing snow. Its study enabled us to verify the functionality of the nival processes and to prove the relative antiquity of some of them. The use of lichenometric techniques, based on the prior construction of a growth curve for lichens of the Rhizocarpon subgenus, has made possible to date sectors of the pronival ramparts. Lichenometric dates show a series of events of geomorphic activity of the snow cover fitting chronologically within the so-called Little Ice Age. It can be deduced from the observation of the current geomorphic dynamics of the snow cover that, although Little Ice Age temperature decrease might be important, particularly in the summer, the role of the variations in snow precipitation must be also taken into consideration. El papel geomorfológico de la nieve desde la Pequeña Edad de Hielo en la Sierra de Ancares (NW España) RESUMEN. -

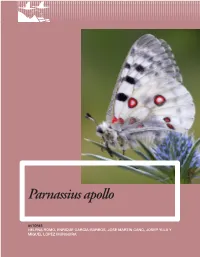

Parnassius Apollo

1 INFORMACIÓN COMPLEMENTARIA Parnassius apollo AUTORES HELENA ROMO, ENRIQUE GARCÍA-BARROS, JOSÉ MARTÍN CANO, JOSEP YLLA Y MIGUEL LÓPEZ MUNGUIRA Esta ficha forma parte de la publicaciónBases ecológicas preliminares para la conservación de las especies de interés comunitario en España: invertebrados, promovida por la Dirección General de Calidad y Evaluación Ambiental y Medio Natural (Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente). Dirección técnica del proyecto Rafael Hidalgo Realización y producción Grupo Tragsa Coordinación general Roberto Matellanes Ferreras y Ramón Martínez Torres Coordinación técnica Juan Carlos Simón Zarzoso Coordinación del grupo de artrópodos Eduardo Galante Coordinación de los grupos de moluscos, cnidarios, equinodermos y anélidos José Templado Edición Eva María Lázaro Varas Maquetación Rafael Serrano Cordón Las opiniones que se expresan en esta obra son responsabilidad de los autores y no necesariamente de la Dirección General de Calidad y Evaluación Ambiental y Medio Natural (Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente). NIPO: 280-12-259-4 3 PRESENTACIÓNPRESENTACIÓN La coordinación general del grupo de artrópodos ha sido encargada a las siguientes instituciones Asociación Española de Entomología Centro Iberoamericano de la Biodiversidad Coordinador: Eduardo Galante Coordinador de especie: José Martín Cano Autores: Helena Romo, Enrique García-Barros, José Martín Cano, Josep Ylla y Miguel López Munguira Fotografía de portada: José Manuel Sesma Agradecimientos: A Biodiversidad Virtual A efectos bibliográficos la obra completa debe citarse como sigue: VV.AA. 2012. Bases ecológicas preliminares para la conservación de las especies de interés comunitario en España: Invertebrados. Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente. Madrid. A efectos bibliográficos esta ficha debe citarse como sigue: Romo, H., García-Barros, E., Martín J., Ylla, J. -

Cuaternario Y Geomorfología ISSN: 0214-1744 Y C G Issne: 2695-8589

Cuaternario y Geomorfología ISSN: 0214-1744 y C G ISSNe: 2695-8589 www.rediris.es/CuaternarioyGeomorfologia/ An exploratory study to test sediments trapped by potholes in Bedrock Rivers as environmental indicators (NW Iberian Massif) Un estudio exploratorio para testar los sedimentos atrapados por marmitas de erosión en ríos sobre roca como indicadores ambientales (NO Macizo Ibérico) Álvarez-Vázquez, M.A. (1); De Uña-Álvarez, E. (1) (1) Department of History, Art and Geography, GEAAT Research Group, Campus of Ourense, University of Vigo. As Lagoas s/n, 32004, Ourense, Spain. [email protected] Abstract The capacity of fluvial potholes to trap sediments, together with the geochemical analysis of their stored sediments for environmental assessment, is an overlooked research topic in small bedrock rivers. The present exploratory study is focused on this issue. It was developed in a small river over rock, in the inland territory of Galicia (NW Iberian Peninsula). The study started from an analysis of the inventoried fluvial potholes to identify suitable forms for sampling, and the collection of sediment samples within them. After this, the determination of the grain texture, mineralogy and content of major and trace elements in sediments were carried out. Potholes with maximum vertical depth from 25 cm to 1 m, located in central and sidewall sectors of the bedrock channel, provided the best conditions for sediment sampling. The sediments collected from six potholes showed predominance of coarse-medium grain size and sand fraction. The rough contents of the major and even trace elements are related with the nature of the more refractory minerals of the bed- rock. -

Discordant Patterns of Nuclear and Mitochondrial Introgression in Iberian Populations of the European Common Frog (Rana Temporaria)

Journal of Heredity Advance Access published February 8, 2012 Journal of Heredity Ó The American Genetic Association. 2012. All rights reserved. doi:10.1093/jhered/esr136 For permissions, please email: [email protected]. Discordant Patterns of Nuclear and Mitochondrial Introgression in Iberian Populations of the European Common Frog (Rana temporaria) ´ MICHAEL VEITH,ANDREA BAUMGART,ALAIN DUBOIS,ANNEMARIE OHLER,PEDRO GALAN,DAVID R. VIEITES, Downloaded from SANDRA NIETO-ROMA´ N, AND MIGUEL VENCES From the Department of Biogeography, Trier University, 54286 Trier, Germany (Veith); the Institute of Zoology, University of Mainz, Mainz, Germany (Baumgart); the De´partement Syste´matique et Evolution, UMS 602, Muse´um National d’Histoire Naturelle, Taxonomie et Collections—Reptiles et Amphibiens, Paris, France (Dubois and Ohler); the Departamento de http://jhered.oxfordjournals.org/ Bioloxı´a Animal, Bioloxı´a Vexetal e Ecoloxı´a, Facultade de Ciencias, Universidade da Corun˜a, A Corun˜a, Spain (Gala´n); the Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales—Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientı´ficas (CSIC), Madrid, Spain (Vieites and Nieto-Roma´n); the Grupo de Ecoloxı´a Evolutiva e da Conservacio´n, Departamento de Ecoloxı´a e Bioloxı´a Animal, Universidade de Vigo, Pontevedra, Spain (Nieto-Roma´n); and the Division of Evolutionary Biology, Zoological Institute, Technical University of Braunschweig, Braunschweig, Germany (Vences). Address correspondence to Michael Veith at the address above, or e-mail: [email protected]. at Universit?tsbibliothek -

024 PANDOZARCO Maquetaci

405 Estudio etnoarqueológico de la evolución de un hábitat estacional de alta montaña en Lugo (Galicia, España) Ethnoarchaeological study of a seasonal high mountain habitat evolution in Lugo (Galicia, Spain) José Manuel Vázquez Varela ([email protected]) Alexandre Luis Vázquez-Rodríguez ([email protected]) Marcos Valcárcel Díaz ([email protected]) Universidad de Santiago de Compostela Resumen: Se presenta un estudio etnoarqueológico sobre una alzada, hábitat estacional de la alta montaña lucense, vinculado con la actividad pastoril estival, y en menor medida con la agrícola para, de acuerdo con los datos obtenidos a través del trabajo de campo antropo- lógico y geográfico, establecer un modelo explicativo del proceso de abandono casi total del yacimiento y de la adquisición de nuevas funciones y significados que ha tomado de un modo reciente. De esta manera es posible entender, a la luz del contexto etnográfico, histó- rico y antropológico, los restos arqueológicos de este lugar de ocupación. Palabras clave: Asentamiento. Arqueología del paisaje. Noroeste península ibérica. Pastoril. Sierra Os Ancares. Abstract: An ethnoarchaeology study about alzadas is presented. The alzada is a high moun- tain seasonal habitat in Lugo´s province, related to temporally pastoral activities and, in a lesser degree, to agriculture, used during the summer season. According to the anthropologic and geographic data obtained from the field research, we establish an explanatory model of the abandonment process and of the acquisition of new meanings and functions of this type of settlement. In this way, it´s possible to understand, within the ethnographic, historic and anthropologic context, the archaeological remnants of this place. -

Folia 4/02-Def

Folia Zool. – 51(4): 307–318 (2002) Genetic differentiation and population structure within Spanish common frogs (Rana temporaria complex; Ranidae, Amphibia) Michael VEITH1*, Miguel VENCES2, David R. VIEITES3, Sandra NIETO-ROMAN3 and Antonio PALANCA3 1 Zoologisches Institut der Universität Mainz, Saarstraße 21, D-55099 Mainz, Germany; e-mail: [email protected] 2 Zoologisches Forschungsinstitut und Museum Alexander Koenig, Adenauerallee 160, 53113 Bonn, Germany; e-mail: [email protected] 3 Laboratorio de Anatomía Animal, Facultade de Ciencias Biolóxicas, Universidade de Vigo, Apdo. 874, 36200 Vigo (PO), Spain; e-mail: [email protected] Received 2 February 2001; Accepted 23 April 2002 Abstract. Genetic differentiation of Rana temporaria from the Pyrenean and Cantabrian mountains in Spain was studied by means of allozyme electrophoresis. 24 loci were analysed in 104 specimens from 15 populations: nine populations from the Pyrenean massif, five populations from the area of the Cantabrian mountain chain (regions of Galicia, Asturias, and Basque Country), and one population from Germany. Three distinct clusters were distinguished by phenetic analysis: (a) the Pyrenean samples and the single population from the Basque Country, (b) the populations from Galicia and Asturias) and (c) the German population. Ordination (PCA) resulted in one principle component (PC1) that separated Cantabrian from Pyrenean populations, and in a second one (PC2) that separated the single German population from the Iberian ones. PC1 indicated introgression that was corroborated by west-east clines in several alleles along the Cantabrian chain. The rather clear separation of the Cantabrian and Pyrenean clusters (mean genetic distance 0.121) suggests that two genetically different subspecies of R. -

The EU-Protected Slug Geomalacus Maculosus: an Investigation Title Into Its Phylogenetics, Population Densities in Conifer Plantations and Its Gut Microbial Community

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. The EU-protected slug geomalacus maculosus: an investigation Title into its phylogenetics, population densities in conifer plantations and its gut microbial community Author(s) Reich, Inga Publication Date 2016-04-04 Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/5631 Downloaded 2021-09-29T06:38:46Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. The EU-protected slug Geomalacus maculosus: An investigation into its phylogenetics, population densities in conifer plantations and its gut microbial community A thesis submitted to the National University of Ireland for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2016 Inga Reich Supervisors and affiliations: Professor Dr Mike Gormally, Applied Ecology Unit, Centre for Environmental Science, School of Natural Sciences, National University of Ireland, Galway Dr Cindy Smith, Microbiology, Centre for Environmental Science, School of Natural Sciences, National University of Ireland, Galway Table of Contents Acknowledgements v Abstract viii Chapter 1. General Introduction 1.1. Scope and objectives 1 1.2. Literature review 1.2.1. General information about G. maculosus 2 1.2.2. Legislation associated with G. maculosus 6 1.2.3. The Lusitanian question 8 1.2.4. Forestry practices in Ireland and implications for G. maculosus in conifer plantations 10 1.2.5. Gut microbial communities of invertebrates 11 1.3. Structure of thesis 13 Chapter 2. Genetic study reveals close link between Irish and Northern Spanish specimens of the protected Lusitanian slug Geomalacus maculosus 2.1. Abstract 15 2.2. -

Texto Completo

Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles, (86) eISSN: 2605-3322 Cómo citar este trabajo: Vila Lage, R., Paül Carril, V., & Trillo Santamaría, J. M. (2020). Autonomous Communities borders and protected areas: an analysis of three biosphere reserves at the interface between Galicia, Asturias and León. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles, (86). https://doi.org/10.21138/bage.2966 Fronteras autonómicas y áreas protegidas: un análisis de tres reservas de la biosfera en la interfaz entre Galicia, Asturias y León Autonomous Communities borders and protected areas: an analysis of three Biosphere Reserves at the interface between Galicia, Asturias and León Roberto Vila Lage [email protected] Valerià Paül Carril [email protected] Juan Manuel Trillo Santamaría [email protected] Departamento de Xeografía Universidade de Santiago de Compostela (España) Resumen Durante las últimas décadas, se ha declarado un elevado número de áreas protegidas transfronterizas (APT). Una de las categorías más destacadas son las reservas de la biosfera transfronterizas. Estas APT suelen concebirse en el marco de las fronteras internacionales; sin embargo, estos instrumentos pueden ser también aplicados en el caso de fronteras internas —entendidas, en este estudio, como los límites administrativos que separan las comunidades Recepción: 08.05.2020 Aceptación: 21.07.2020 Publicación: 22.08.2020 Este trabajo se publica bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial 4.0 Internacional. autónomas (CCAA)–. Este artículo procura trasladar las bases teóricas de la conservación transfronteriza a tres reservas de la biosfera situadas en el límite entre Galicia, Asturias y León. Se trata de la Reserva de la Biosfera de Río Eo, Oscos y Terras de Burón; la Reserva de la Biosfera de Os Ancares Lucenses e Montes de Cervantes, Navia e Becerreá; y la Reserva de la Biosfera de los Ancares Leoneses. -

Plan De Acción Da Reserva Da Biosfera Os Ancares Lucenses E

Plan de Acción da Reserva de Biosfera Os Ancares Lucenses, Montes de Navia, Cervantes e Becerreá 17 de decembro de 2013 Plan de Acción da Reserva de Biosfera Os Ancares Lucenses, Montes de Navia, Cervantes e Becerreá Plan de Acción da Reserva de Biosfera Os Ancares Lucenses, Montes de Navia, Cervantes e Becerreá 17 de decembro de 2013 Dirección Técnica José Ramón Gómez Besteiro Sonsoles López Izquierdo José Antonio Mourelle Cillero Leticia Vilar Pumares Pablo Rivera Capón Andrea Macho Benito Mª Ángeles González Machado Deputación Provincial de Lugo Equipo redactor Pablo Ramil Rego Javier Ferreiro da Costa Manuel Antonio Rodríguez Guitián Luis Gómez-Orellana Rodríguez Boris Alejandro Hinojo Sánchez Marco Antonio Rubinos Román Carmen Cillero Castro Grupo de Investigación 1934 -TB IBADER - Campus de Lugo Universidade de Santiago de Compostela Plan de Acción da Reserva de Biosfera Os Ancares Lucenses, Montes de Navia, Cervantes e Becerreá Plan de Acción da Reserva de Biosfera Os Ancares Lucenses, Montes de Navia, Cervantes e Becerreá ÍNDICE 1. Diagnóstico e antecedentes 1 1.1 Función de conservación 1 1.2 Función de desenvolvemento sostible 10 1.3 Función de apoio loxístico 13 1.4 Análise DAFO 15 2. Encadre legal e normativo normativo 16 2.1 17 Marco Estatutario e Estratexia de Sevilla 2.2 18 Estratexia e Plan de Acción de Lanzarote 2.3 18 Plan de Acción de Madrid 2.4 20 Plan de Acción de Montseny 3. Xustificación e obxectivos 21 4. Liñas de Acción 23 A. Xestión adaptativa da Reserva 25 B. Conservación do patrimonio natural e cultural 29 C. -

Micolucus Nº 3 2016

Micolucus NÚMERO 3 • ANO 2016 Limiar ..................................................................................... 1 Micolucus é unha publicación da Sociedade Micolóxica Lucus, Biodiversidade fúnxica da Reserva da Biosfera Terras do CIF: G27272954 Miño: Chromocyphella muscicola (Fr.) Donk. JOSE CASTRO .. 2 Depósito Legal: LU 140-2014 Algunas especies de macromicetos presentes en un jaral de ISSN edición impresa: 2386-8872 ISSN edición dixital: 2387-1822 Cistus ladanifer L. en el municipio de A Rúa de Valdeorras (Ourense, NO península ibérica) III. JULIÁN ALONSO ............ 7 REDACCIÓN E Aportaciones al conocimiento del género Russula en Galicia II. COORDINACIÓN: Subsección Sardoninae Singer. JOSÉ MARÍA TRABA VELAY.... 21 Julián Alonso Díaz José Castro Ferreiro Introducción a Xylariaceae Tul. & C. Tul. Descripción de Benito Martínez Lobato algunas especies frecuentes en Galicia. Juan Antonio Martínez Fidalgo JOSÉ MANUEL CASTRO MARCOTE ....................................... 32 Alfonso Vázquez Fraga Notas sobre la familia Cantharellaceae en el noroeste de la José Manuel Fernández Díaz península ibérica (VI): Una nueva combinación y una nueva forma Cristina Gayo Cancelas de Cantharellus romagnesianus. JAIME B. BLANCO-DIOS ......... 41 Os artigos remitidos a Esporas pardas en Galicia. PATRICE LAINÉ; EVA GARCÍA .... 47 Micolucus son revisados por Hapalopilus nidulans (Fr.) P. Karst., un políporo tóxico. asesores externos antes de ser JOSÉ MARÍA COSTA LAGO .................................................... 52 aceptados ou rexeitados. Estudios sobre Lepiota erminea (Fr. : Fr.) P. Kumm., una Os autores que envíen artigos especie variable. AGUSTÍN CABALLERO ............................... 56 para publicar na revista Micolucus deben axustarse a Algúns Ascomycetes de tonalidades escuras relativamente unhas normas que poden comúns. MANUEL POSE CARRACEDO . ................................ 62 consultarse en: www.smlucus.org/UserFiles/Files Importancia de sabores e aromas na identificación de /Micolucus/Normas_Micolucus. -

(Coleoptera) De La Península Ibérica E Islas Baleares

Bol. S.E.A., nº 30 (2002) : 1—32. CATÁLOGO DE LOS SILPHIDAE Y AGYRTIDAE (COLEOPTERA) DE LA PENÍNSULA IBÉRICA E ISLAS BALEARES Fernando Prieto Piloña 1 & Javier Pérez Valcárcel 2 Ilustraciones y fotografía: Fernando Rey-Daluz 3 1 Avda. Camelias, 21-2º. E-36202 Vigo – [email protected] 2 r/ Dolores Rodríguez Sopeña, 9-3ºD. E-15007 A Coruña – [email protected] 3 Apdo. correos 143 E-36201 Vigo – [email protected] Resumen: Se presenta un estudio faunístico de las familias Silphidae y Agyrtidae (Coleoptera) iberobaleares. Se da una visión de conjunto de la biología y biogeografía, además de aportarse claves de identificación de los adultos y una revisión bibliográfica exhaustiva de las dos familias. El trabajo se completa con mapas de distribución de todas las especies y fotografía o dibujo del habitus de la mayor parte de ellas. Se confirma la presencia de Necrophilus subterraneus (Dahl, 1807) en la Península Ibérica. Palabras Clave: Coleoptera, Silphidae, Agyrtidae, faunística, claves de identificación, mapas de distribución, Península Ibérica, Islas Baleares. Bibliographical and faunal catalogue of Silphidae and Agyrtidae (Coleoptera) of the Iberian Peninsula and Balearic Islands Abstract: A faunal study of the carrion beetles (Coleoptera: Silphidae and Agyrtidae) of Iberian Peninsula and Balearic Islands is presented. An overview of their biology and biogeography is given, as well as identification keys to the adults and a comprehensive bibliographic revision of the two families. Distribution maps are given for all species as well as habitus pictures or drawings for most species. The presence of Necrophilus subterraneus (Dahl, 1807) on the Iberian Peninsula is confirmed.