Ableism and Heteronormativity in Science Fiction Wälivaara, Josefine 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deconstructing Sodom and Gomorrah: a Historical Analysis Of

Deconstructing Sodom and Gomorrah: A Historical Analysis of the Mythology of Black Homophobia A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Lance E. Poston December 2018 © 2018 Lance E. Poston. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Deconstructing Sodom and Gomorrah: A Historical Analysis of the Mythology of Black Homophobia by LANCE E. POSTON has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Katherine Jellison Professor of History Joseph Shields Interim Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT POSTON, LANCE E., PH.D., December 2018, History Deconstructing Sodom and Gomorrah: A Historical Analysis of the Mythology of Black Homophobia Director of Dissertation: Katherine Jellison This dissertation challenges the widespread myth that black Americans make up the most homophobic communities in the United States. After outlining the myth and illustrating that many Americans of all backgrounds had subscribed to this belief by the early 1990s, the project challenges the narrative of black homophobia by highlighting black urban neighborhoods in the first half of the twentieth century that permitted and even occasionally celebrated open displays of queerness. By the 1960s, however, the black communities that had hosted overt queerness were no longer recognizable, as the public balls, private parties, and other spaces where same-sex contacts took place were driven underground. This shift resulted from the rise of the black Civil Rights Movement, whose middle-class leadership – often comprised of ministers from the black church – rigorously promoted the respectability of the race. -

Educators Managing and Reproducing

THE SOUND OF SILENCE: EDUCATORS MANAGING AND REPRODUCING HETERONORMATIVITY IN MIDDLE SCHOOLS by JULIA I. HEFFERNAN A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Education Studies and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2010 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Julia I. Heffernan Title: The Sound of Silence: Educators Managing and Reproducing Heteronormativity in Middle Schools This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Education Studies by: Dr. Jerry Rosiek Chairperson Dr. Joanna Goode Member Dr. Krista Chronister Member Dr. Michael Hames-Garcia Outside Member and Richard Linton Vice President for Research and Graduate Studies/Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded December 2010 ii © 2010 Julia I. Heffernan iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Julia I. Heffernan Doctor of Philosophy College of Education December 2010 Title: The Sound of Silence: Educators Managing and Reproducing Heteronormativity in Middle Schools Approved: _______________________________________________ Dr. Jerry Rosiek Recent national studies indicate that well over three quarters of sexual and gender identity minority high school students are subjected to verbal and physical violence related to their gender identity or sexuality. An array of sociological studies has found that adolescents openly acknowledge homophobic justification for past verbal harassment and abuse, and masculinity studies associate this abuse with affirming a normative masculinity. This study seeks to determine what conditions could contribute to the social production of such endemic violence and simultaneously preserve a pervasive silence about its social origins. -

DEEP SPACE NINE® on DVD

Star Trek: DEEP SPACE NINE® on DVD Prod. Season/ Box/ Prod. Season/ Box/ Title Title # Year Disc # Year Disc Abandoned, The 452 3/1994 3/2 Emissary, Part I 401 1/1993 721 1/1 Accession 489 4/1996 4/5 Emissary, Part II 402 1/1993 Adversary, The 472 3/1995 3/7 Emperor's New Cloak, The 562 7/1999 7/3 Afterimage 553 7/1998 7/1 Empok Nor 522 5/1997 5/6 Alternate, The 432 2/1994 2/3 Equilibrium 450 3/1994 3/1 Apocalypse Rising 499 5/1996 5/1 Explorers 468 3/1995 3/6 Armageddon Game 433 2/1994 2/4 Extreme Measures 573 7/1999 7/6 Ascent, The 507 5/1996 5/3 Facets 471 3/1995 3/7 Assignment, The 504 5/1996 5/2 Family Business 469 3/1995 3/6 Babel 405 1/1993 1/2 Far Beyond the Stars 538 6/1998 6/4 Badda-Bing, Badda-Bang 566 7/1999 7/4 Fascination 456 3/1994 3/3 Bar Association 488 4/1996 4/4 Favor the Bold 529 6/1997 6/2 Battle Lines 413 1/1993 1/4 Ferengi Love Songs 518 5/1997 5/5 Begotten, The 510 5/1997 5/3 Field of Fire 563 7/1999 7/4 Behind the Lines 528 6/1997 6/1 For the Cause 494 4/1996 4/6 Blaze of Glory 521 5/1997 5/6 For the Uniform 511 5/1997 5/4 Blood Oath 439 2/1994 2/5 Forsaken, The 417 1/1993 1/5 Body Parts 497 4/1996 4/7 Hard Time 491 4/1996 4/5 Broken Link 498 4/1996 4/7 Heart of Stone 460 3/1995 3/4 Business as Usual 516 5/1997 5/5 Hippocratic Oath 475 4/1995 4/1 By Inferno's Light 513 5/1997 5/4 His Way 544 6/1998 6/5 Call to Arms 524 5/1997 5/7 Homecoming, The 421 2/1993 2/1 Captive Pursuit 406 1/1993 1/2 Homefront 483 4/1996 4/3 Cardassians 425 2/1993 2/2 Honor Among Thieves 539 6/1998 6/4 Change of Heart 540 6/1998 6/4 House -

The Klingon Empire 1.1 – the Homeworld 4 1.2 – Important Places 5 1.3 – History of the Empire 6

INSTITUTE OF ALIEN STUDIES Klingon Warrior Academy Warrior’s Manual This document is a publication of STARFLEET Academy - A department of STARFLEET, The International Star Trek Fan Association, Inc. It is intended for the private use of our members. STARFLEET holds no claims to any trademarks, copyrights, or properties held by CBS Paramount Television, any of its subsidiaries, or on any other company's or person's intellectual properties which may or may not be contained within. The contents of this publication are copyright (c)2008 STARFLEET, The International Star Trek Fan Association, Inc. and the original authors. All rights reserved. No portion of this document may be copied or republished in any or form without the written consent of the Commandant, STARFLEET Academy or the original author(s). All materials drawn in from sources outside of STARFLEET are used per Title 17, Chapter 1, Section 107: Limitations on exclusive rights: Fair Use, of the United States code. The material as used is for educational purposes only and no profit is made from the use of the material. STARFLEET and STARFLEET Academy are granted irrevocable rights of usage of this material by the original author. Contributors: Larry French, Carol Thompson, and Wayne L. Killough, Jr., Gary Hollifield, Jr., Eric Schulman,Dewald de Coning, and George Pimentel Published October 2008 Revised March 2011 Updated October 2014 Material herein was copied or summarized from www.ditl.org , http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Klingon and linked pages, http://memory-alpha.org/en/wiki/ , http://startrek.wikia.com/wiki/Klingon , http://en.hiddenfrontier.com/index.php/Klingon , The Klingon Dictionary, Klingon for the Galactic Traveler, Star Trek Encyclopedia: Expanded Version, and various Star Trek episodes and licensed novels. -

A Narrative Exploration Into Sexuality, Sport, and Masculinity

SINGLED OUT: A NARRATIVE EXPLORATION INTO SEXUALITY, SPORT, AND MASCULINITY Daniel M. Sierra A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF EDUCATION MAY 2013 Committee: Dr. Amanda Koba, Advisor Dr. Vikki Krane Dr. Sungho Cho ii ABSTRACT Dr. Amanda Koba, Advisor At the present time, gay men in sport are still a largely unexamined group. Currently, Jason Collins of the NBA is the only openly gay male athlete competing in the four major professional team sports in the United States: football, basketball, baseball, and hockey. Much of the research that does exist is based on Connell’s (1990) theory of hegemonic masculinity. This theory contends that society values a single form of masculinity over all others, and that sport in particular functions to reproduce this singular identity, valorizing traits such as strength, toughness, and aggression (Connell, 1990). This system creates hierarchies, with the most hegemonically masculine men at the top of the structure, and in a position to dominate over women and less masculine men (Anderson, 2005; Messner, 2002). Historically, homophobia has acted as the main tool to police the actions of men, especially in a sport context (Anderson, 2011; Pronger, 1990). Thus, it is an immense struggle for gay male athletes to come out and express their sexuality openly on their teams. New research is emerging that suggests the climate in sport is changing, and that greater social acceptance of homosexuality is making its way into the realm of sport. This qualitative, narrative analysis aims to provide a rich examination into the experiences and perceptions of gay male athletes. -

Identity Negotiation and Management Among Queer, Peace Corps Volunteers

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 10-11-2015 Life is Calling...How Far Will You Go...Back in the Closet? Identity Negotiation and Management Among Queer, Peace Corps Volunteers Kate Elizabeth Slisz Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons, African Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Slisz, Kate Elizabeth, "Life is Calling...How Far Will You Go...Back in the Closet? Identity Negotiation and Management Among Queer, Peace Corps Volunteers" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 546. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/546 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIFE IS CALLING…HOW FAR WILL YOU GO…BACK IN THE CLOSET? IDENTITY NEGOTIATION AND MANAGEMENT AMONG QUEER, PEACE CORPS VOLUNTEERS Kate E. Slisz 273 Pages There is little to no research surrounding the experiences of queer, foreign-aid workers. To address this gap, a study was conducted to explore how compulsory heterosexuality affects the social construction of sexuality in societies where queer, foreign-aid workers serve and how this influences their identity negotiation and management processes. Participants consisted of ten self-identified queer, Returned Peace Corps Volunteers (RPCVs), as well as, the researcher herself who also identifies as queer. Data was gathered through both semi-structured interviews and autoethnographic research. -

STAR TREK: the NEXT GENERATION "Encounter at Farpoint" by D.C. Fontana and Gene Roddenberry This Script Is Not F

STAR TREK: THE NEXT GENERATION "Encounter at Farpoint" by D.C. Fontana and Gene Roddenberry This script is not for publicaion or reproduction. No one is authorized to dispose of the same. If lost or destroyed, please notify the Script Department. FINAL DRAFT April 13, 1987 TEASER FADE IN: 1 EXT. SPACE - STARSHIP (OPTICAL) The U.S.S. Enterprise NCC 1701-D traveling at warp speed through space. PICARD V.O. Captain's log, stardate 42353.7. Our destination is planet Cygnus IV, beyond which lies the great unexplored mass of the galaxy. 2 OTHER INTRODUCTORY ANGLES (OPTICAL) on the gigantic new Enterprise NCC 1701-D. PICARD V.O. My orders are to examine Farpoint, a starbase built there by the inhabitants of that world. Meanwhile ... 3 INT. ENGINE ROOM Huge, with a giant wall diagram showing the immensity of this Galaxy Class starship. PICARD V.O. (continuing) ... I am becoming better acquainted with my new command, this Galaxy Class U.S.S. Enterprise. 4 CLOSER ON VESSEL DIAGRAM Showing the details and size of this enormous starship. PICARD V.O. I am still somewhat in awe of its size and complexity. 5 INT. LOUNGE DECK With its huge windows revealing the immense span of the Starship's outer surface. 5 CONTINUED: PICARD V.O. (continuing) ... my crew we are short in several key positions, most notably ... 6 INT. BRIDGE - WIDE ANGLE PICARD, TROI, and DATA seated in the command area. Starfleet LIEUTENANT WORF, a young Klingon, is at the "Ops" station and a SUPERNUMERARY is at "Conn". PICARD V.O. -

GLI AMORI E GLI AFFETTI DEL SIMBIONTE DAX Il Simbionte Dax Ha Vissuto Diverse Vite, Ed Ha Avuto Molte Relazioni Sentimentali, Ma

GLI AMORI E GLI AFFETTI DEL SIMBIONTE DAX Il simbionte Dax ha vissuto diverse vite, ed ha avuto molte relazioni sentimentali, ma forse la più singolare è stata quella che ha legato Jadzia con il Klingon Worf. Molti dei precedenti ospiti Trill del simbionte sono diventati genitori: Dax ha avuto nove figli, Lela, la prima ospite, ha avuto un figlio di nome Ahjess; il secondo, Tobin, è stato padre di Raifi. Audrid, la quarta ospite, ha avuto un figlio, Gran, ed una figlia, Neema. Mentre si trovava sulla Terra come giudice di una gara ginnastica, Emony, la terza ospite, ebbe una breve relazione con uno studente di nome Leonard McCoy. Quando una successiva ospite apprese che McCoy era diventato un medico, non ne restò sorpresa, ricordandosi che l’ufficiale della Flotta Stellare “ aveva mani da chirurgo “. IL RITORNO DI PASSATI AMORI Arrogante e pieno di sé come solo un pilota può esserlo, Torias Dax, il quinto ospite, s’innamorò di un’altra Trill unita, Nilani Kahn. Benché l’avesse in seguito sposata, Torias si mostrava infastidito dall’apprensione manifestata da Nilani. Forse, tuttavia sua moglie non sbagliava nel cercare di dissuaderlo dall’eccesso di temerarietà giacché, nel 2285, Torias perse la vita in un atterraggio di fortuna mentre collaudava una navetta. L’amore che Torias provava per Nilani, e l’improvvisa fine della loro relazione, ebbero un profondo impatto su Dax. Nel 2372, Jadzia Dax incontra Lenara Kahn, l’attuale ospite del simbionte Kahn, su DS9 ( Rejoined ). Cercando di superare il disagio per la situazione, le due donne scoprono che hanno in comune più di quanto avessero mai avuto Torias e Nilani. -

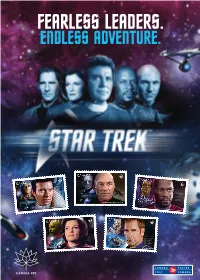

Commanding Collectibles

COMMANDING COLLECTIBLES Beam Admiral James T. Kirk and Captain Jean-Luc Picard aboard with these limited edition framed prints. Both include two Official First Day Covers and a mat etched with the delta shield. Only Kirk’s enlargement is signed by Star Trek’s first star, Montréal-born William Shatner. Only 600 available, framed, signed and numbered Authentic signature $24995 Limited edition framed print 23.75 in. x 23 in. / 603 mm x 584 mm 342141 Only 600 available $17995 Limited edition framed print 23.75 in. x 23 in. / 603 mm x 584 mm 342142 From Canada or the U.S. From other countries canadapost.ca/startrek 1-800-565-4362 902-863-6550 DETAILS APRIL 2017 | No.4 Captain’s log Stardate: April 27, 2017. A second year on the edge of the final frontier concludes our exploration of the best of Star Trek™. We’ve discovered seven new stamps and added them to our collection. Led by James T. Kirk (played by Montréal-born William Shatner), they feature three Starfleet captains who followed in his footsteps and one who made humanity’s first foray into interstellar space. Although we have made some great discoveries, our mission has also been dangerous. Starfleet’s finest share their stamps with some of the galaxy’s most nefarious villains. We also learned of a tiny but intrepid shuttlecraft coil stamp and a large, looming Borg design … On March 15, 2017, in Studio City, California, William Shatner signed enlargements of the Admiral TRANSMISSION INTERRUPTED … James T. Kirk stamp, which are the focus of the limited edition framed print. -

Spiegeluniversum Ebook

SPIEGELUNIVERSUM PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lanie Goodell | 424 pages | 21 Nov 2020 | Independently Published | 9798687396721 | English | none Spiegeluniversum PDF Book USS Stargazer. Is it worthy of your precious binge watching hours? Adam Pearle August 22, at pm. De vraag wat er was voor de oerknal is daarmee ook opgelost: 27, 6 miljard jaar geleden was het toen net nu. Dat komt omdat op planckschaal de ruimtetijd golft, borrelt en bruist als een woeste zee. Notwendige Notwendige. Gruven Tom August 22, at pm. Delcara vanished, never to return, after attempting to use her vessel to break the Warp 10 barrier. Was ist die passende Uniform zu meinem Wunschcharakter? Melody Mackey August 22, at pm. Using the information gleaned from Troi, the most powerful members of the Betazed Resistance used their telepathic powers to empathically overload the minds of the Jem'Hadar occupation forces. He was honored by Sokketh who resigned from the Federation Council to take Picard's role as ambassador. So without further ado, happy bingeing Trekkies! Kirk during their brief meeting in the Nexus : to never accept a promotion that would take him away from the Enterprise , as it was when he was in the captain's chair of that ship that he was best suited to make a difference. Eventually Picard and the Enterprise crew learned that Ba'ku's metaphasic rings were like a fountain of youth, and Admiral Matthew Dougherty and the Son'a leader, Ru'afo were determined to have the planet. In late , the Thallonian Empire in Sector G collapsed and thousands of refugees were yearning to escape. -

Exploring Issues of Sex, Gender and Race in Cult TV

Representation: Exploring Issues of Sex, Gender and Race in Cult Television Lorna Jowett How realistic is it to expect cult television, something many consider a niche market, to impact on perceptions of sex, gender or race? Yet television fiction, striving to remain relevant and credible to audiences, must negotiate questions of identity that change as understanding of ourselves and our society changes. In turn, television’s popular nature makes these negotiations influential. Television drama deals with sex, gender, and race because it tends to centre on character. Often, representations are mobilised in a liberal humanist fashion which embraces diversity and freedom of expression but does not acknowledge the political significance of identity. Despite successive waves of feminism and gay rights activism, sex and gender tend to be depoliticised because they may be dealt with as individual concerns, playing down their social significance. Race, perhaps especially in the US, is seen to be more political. Naturally, the mainstream, commercial nature of television means that sensitive subjects will always be handled carefully, often leading to a “least offensive programming” strategy (though what is considered offensive will vary from country to country and from individual to individual). Yet the increasing segmentation of television markets has caused a shift to what some describe as “narrowcasting,” and in an industry that now values products aimed at specific audiences, cult television has come into its own. Cult, through its negotiation of genre, potentially enables representations to be less mainstream. Furthermore, given the overlap between 1 cult and some “quality” television, its audience may be more willing to embrace challenging representation as part of contemporary television drama. -

Super! Drama TV July 2020

Super! drama TV July 2020 ▶Programs are suspended for equipment maintenance late at night on the 22th from 3:55 to 4:00 and the 29th from 3:55 to 4:00. Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese (ET) Wed.1 Thu,2 Fri.3 Sat.4 Sun.5 (ET) 6:00 06:00 STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE 06:00 STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE 06:00 STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE 06:00 STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE 06:00 STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE 6:00 Season 4 Season 4 Season 4 Season 4 Season 4 #5 #6 #7 #8 #9 6:30 「INDISCRETION」 「REJOINED」 「LITTLE GREEN MEN」 「STARSHIP DOWN」 「THE SWORD OF KAHLESS」 6:30 7:00 07:00 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO Season 1 07:00 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO Season 1 07:00 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO Season 1 07:00 CAPTAIN SCARLET AND THE 07:00 THE CROSSING 7:00 #9 「SLINGSHOT」 #11 「SKYHOOK」 #13 「HEAVY METAL」 MYSTERONS #9 #15 「SEEK AND DESTROY」 「Hope Smiles from the Threshold」 7:30 07:30 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO Season 1 07:30 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO Season 1 07:30 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO Season 1 07:30 JOE 90 7:30 #10 「TUNNELS OF TIME」 #12 「UNDER PRESSURE」 #14 「FALLING SKIES」 #15 「PROJECT 90」 8:00 08:00 SCORPION Season 4 08:00 SCORPION Season 4 08:00 SCORPION Season 4 08:00 THE MYSTERIES OF LAURA 08:00 THE CROSSING 8:00 #6 #7 #8 #15 「The Mystery of the Alluring Au Pair」 #10 「Queen Scary」 「Go With the Flo(Rence)」 「Faire Is Foul」 「The Androcles Option」 8:30 8:30 9:00 09:00 information [J] 09:00 information [J] 09:00 information [J] 09:00 information [J] 09:00 information [J] 9:00 9:30 09:30 DESIGNATED SURVIVOR Season 2 09:30 MACGYVER Season 2 [J] 09:30 THE BLACKLIST Season 7 09:30 NCIS: NEW ORLEANS Season 5 09:30 S.W.A.T.