ABSTRACT “Not Only Creators, but Also Interpreters”: Artist/Curators in Contemporary Practice Jennifer L. Restauri, M.A. Me

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kayaks Quyanaasinaq

FREE ADMISSION November 25 – December 23 Looking for something to do with your friends and family this holiday season? If you’re a current member, you already enjoy free admission to the Alutiiq Museum. Now, thanks to the generous support of KeyBank, everyone gets in for free between November 25 and December 23! Add a little local culture to your holidays with a visit to the Alutiiq Museum, a gift to our community from KeyBank. The Quarterly Newsletter of the Alutiiq Museum Volume 20, Issue 4 | Spring 2016 New Exhibit Features Qayat - Kayaks rom driftwood, animal skins, tendon and baleen, Alutiiq people Ethnology the boat is a rare, complete example of the graceful, light, Fcreated qayat that were expertly designed for Kodiak’s notoriously and flexible Alutiiq qayaq. windy waters. Working with stone and bone tools, and using the Adjacent to the historic vessel is a qayaq frame. Carved by Alfred proportions of the human body as a measuring guide, men built boats Naumoff in 2014, this piece illustrates the internal framework of that permitted swift, secure travel through ocean waters. For the traditional boats. Pieces of a qayaq were never nailed together, but Alutiiq, qayat were a lifeline. They allowed people to harvest fish and carefully lashed to allow the boat to bend in the waves. Naumoff is sea mammals from the ocean, to travel and trade over great distances, one of just a handful of contemporary Alutiiq kayak builders, and his and to carry supplies home. In coastal Alaska, the qayaq remains a knowledge has been informed by studies of historic boats. -

From Surrealism to Now

WHAT WE CALL LOVE FROM SURREALISM TO NOW IMMA, Dublin catalogue under the direction of Christine Macel and Rachael Thomas [Cover] Wolfgang Tillmans, Central Nervous System, 2013, inkjet print on paper mounted on aluminium in artist’s frame, frame: 97 × 82 cm, edition of 3 + 1 AP Andy Warhol, Kiss, 1964, 16mm print, black and white, silent, approx. 54 min at 16 frames per second © 2015 THE ANDY WARHOL MUSEUM, PITTSBURG, PA, COURTESY MAUREEN PALEY, LONDON. © WOLFGANG TILLMANS A MUSEUM OF CARNEGIE INSTITUTE. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. FILM STILL COURTESY OF THE ANDY WARHOL MUSEUM. PHOTO © CENTRE POMPIDOU, MNAM-CCI, DIST. RMN-GRAND PALAIS / GEORGES MEGUERDITCHIAN CONTENTS E 1 FOREWORD Sarah Glennie 6 WHAT WE CALL LOVE Christine Macel 13 SURREALISM AND L’AMOUR FOU FROM ANDRÉ BRETON TO HENRIK OLESEN / FROM THE 1920s TO NOW 18 ANDRÉ BRETON AND MAD LOVE George Sebbag 39 CONCEPTUAL ART / PERFORMANCE ART FROM YOKO ONO TO ELMGREEN AND DRAGSET / FROM THE 1960s TO NOW 63 NEW COUPLES FROM LOUISE BOURGEOIS TO JIM HODGES / FROM THE 1980s TO NOW 64 AGAINST DESIRE: A MANIFESTO FOR CHARLES BOVARY? Eva Illouz 84 THE NEUROBIOLOGY OF LOVE Semir Zeki 96 LOVE ACTION Rachael Thomas WHAT 100 LIST OF WORKS 104 BIBLIOGRAPHY WE CALL LOVE CHAPTER TITLE F FOREWORD SARAH GLENNIE, DIRECTOR The Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) is pleased to present this publication, which accompanies the large scale group exhibition, What We Call Love: From Surrealism to Now. This exhibition was initially proposed by Christine Macel (Chief Curator, Centre Pompidou), who has thoughtfully curated the exhibition alongside IMMA’s Rachael Thomas (Senior Curator: Head of Exhibitions). -

The Art of Resilience Acknowledgments

The Art of 2019 Catalog Disclaimer All images of the artworks in this publication are the property of the respective artists. On the cover (clockwise from top left) Yky, Shakes p. 12 Justin Wood, March Towards Extinction p. 6 Pitsho Mafolo, Redefining Life p. 2 Adrien Segal, Trends in Water Use p. 19 The Art of The World Bank Group, Washington, DC, October 29, 2019–January 19, 2020 The ArtScience Museum and Singapore Expo Center, Singapore, May 16, 2020–May 24, 2020 artofresilience.art Table of Contents Acknowledgments p. iii Foreword p. iv Introduction p. vi Overview p. vi Why Art? p. vi The Process p. vii The Artwork p. viii Our Hope p. x Art as a Call to Action p. 1 Art-Science Collaboration as a Resource for Innovation p. 17 Engaging Communities Through Public and Participatory Arts p. 25 Guidance for Practitioners p. 33 ii :: The Art of Resilience Acknowledgments Contributors JD Talasek, Director of Cultural Programs, The Art of Resilience was conceived by the National Academy of Sciences Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Emma Phillips Solomon, Sr. Disaster Risk Recovery (GFDRR) Labs team and the World Management Specialist, GFDRR Labs Bank Group Art Program. The exhibition Robert Soden, Sr. Disaster Risk Management features artists selected through a competitive Consultant, GFDRR Labs process. Participation was open to any emerging or established artist using his, her, Research and Catalogue Entries or their art to help build society’s resilience to Juliana Biondo, Assistant Curator and Project natural hazards. Artworks of any medium were Manager, World Bank Group Art Program accepted, and artists included any person Editorial Coordination engaged in creative endeavors. -

Introduction to Art Making- Motion and Time Based: a Question of the Body and Its Reflections As Gesture

Introduction to Art Making- Motion and Time Based: A Question of the Body and its Reflections as Gesture. ...material action is painting that has spread beyond the picture surface. The human body, a laid table or a room becomes the picture surface. Time is added to the dimension of the body and space. - "Material Action Manifesto," Otto Muhl, 1964 VIS 2 Winter 2017 When: Thursday: 6:30 p.m. to 8:20p.m. Where: PCYNH 106 Professor: Ricardo Dominguez Email: [email protected] Office Hour: Thursday. 11:00 a.m. to Noon. Room: VAF Studio 551 (2nd Fl. Visual Art Facility) The body-as-gesture has a long history as a site of aesthetic experimentation and reflection. Art-as-gesture has almost always been anchored to the body, the body in time, the body in space and the leftovers of the body This class will focus on the history of these bodies-as-gestures in performance art. An additional objective for the course will focus on the question of documentation in order to understand its relationship to performance as an active frame/framing of reflection. We will look at modernist, contemporary and post-contemporary, contemporary work by Chris Burden, Ulay and Abramovic, Allen Kaprow, Vito Acconci, Coco Fusco, Faith Wilding, Anne Hamilton, William Pope L., Tehching Hsieh, Revered Billy, Nao Bustamante, Ana Mendieta, Cindy Sherman, Adrian Piper, Sophie Calle, Ron Athey, Patty Chang, James Luna, and the work of many other body artists/performance artists. Students will develop 1 performance action a week, for 5 weeks, for a total of 5 gestures/actions (during the first part of the class), individually or in collaboration with other students. -

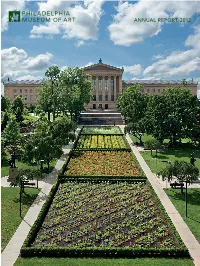

Annual Report 2012

BOARD OF TRUSTEES 4 LETTER FROM THE CHAIR 6 A YEAR AT THE MUSEUM 8 Collecting 10 Exhibiting 20 Teaching and Learning 30 Connecting and Collaborating 38 Building 44 Conserving 50 Supporting 54 Staffing and Volunteering 62 CALENDAR OF EXHIBITIONS AND EVENTS 68 FINANCIAL StATEMENTS 72 COMMIttEES OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES 78 SUPPORT GROUPS 80 VOLUNTEERS 83 MUSEUM StAFF 86 A REPORT LIKE THIS IS, IN ESSENCE, A SNAPSHOT. Like a snapshot it captures a moment in time, one that tells a compelling story that is rich in detail and resonates with meaning about the subject it represents. With this analogy in mind, we hope that as you read this account of our operations during fiscal year 2012 you will not only appreciate all that has been accomplished at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, but also see how this work has served to fulfill the mission of this institution through the continued development and care of our collection, the presentation of a broad range of exhibitions and programs, and the strengthening of our relationship to the com- munity through education and outreach. In this regard, continuity is vitally important. In other words, what the Museum was founded to do in 1876 is as essential today as it was then. Fostering the understanding and appreciation of the work of great artists and nurturing the spirit of creativity in all of us are enduring values without which we, individually and collectively, would be greatly diminished. If continuity—the responsibility for sustaining the things that we value most—is impor- tant, then so, too, is a commitment to change. -

Fort Worth Master Plan Update

2017 Fort Worth Public Art Master Plan update Adopted by Fort Worth City Council 10.17.17 Barbara Goldstein and Associates with Cusick Consulting Ammonite Intervention, 2015 Lars Stanley Painted steel Riverside Bridge over Fossil Creek Image courtesy of the artist Public Art Master Plan Update Fort Worth Contents I. Executive Summary 5 II. Introduction 9 III. Development of the Public Art Plan Update 11 IV. Key Findings 15 V. Vision and Goals 19 VI. Recommendations 21 VII. Implementation 32 VIII. Appendicies 35 Front Cover Intimate Apparel and Pearl Earrings, 2005 Donald Lipski Mixed media Fort Worth Convention Center Image by Ralph Lauer Back Cover Legacy of the Land (detail), 2009 Steve Teeters Rodeo Plaza, Historic Stockyards I Executive Summary 4 As one of the nation’s fastest growing cities, we are continually investing in infrastructure and facilities to serve our residents. It is important that we engage the talents of artists to enhance our built environment and give it that human touch. Not only does it contribute to our residents’ quality of life, public art also attracts economic investments and tourism. —Mayor Betsy Price Tabachin Ribbon, 2010 Yvonne Domenge Painted steel Fort Worth Municipal Court Building Public Art Master Plan Update Fort Worth I Executive Summary 5 Background In October 2016, the City’s public art program, Fort Worth Public Art (FWPA), marked an important milestone— fifteen years of working with artists and communities to create distinct and memorable places. Much like Fort Worth, the public art program has matured and evolved in the years since its establishment. The fifteen-year mark offers the perfect opportunity to review the 2003 master plan, and assess the program along with the ensuing collection. -

Electronic Arts Intermix New Works 2005 - 2006

Electronic Arts Intermix New Works 2005 - 2006 THE LEADING DISTRIBUTOR OF ARTISTS’ VIDEO Electronic Arts Intermix New Works 2005-2006 New Works 2005-2006 features a remarkable range of video, film, and new media works that have recently been added to the EAI collection. We are pleased to introduce a number of emerging and established artists, including Cory Arcangel, video game and computer hacker extraordinaire; JODI, the pioneering Web art provocateurs, and Lawrence Weiner, one of the most significant figures in Conceptual Art. We are also pleased to launch EAI Projects, a new initiative to present and promote emerging artists working in innovative moving image media, including the international collective Bernadette Corporation; performance artist Shana Moulton; digital artist Takeshi Murata; and multidisciplinary artist Seth Price. Also featured are new video works by emerging and established artists, including Sophie Calle, Seoungho Cho, Tony Cokes, Dan Graham, Mary Lucier, Muntadas, Paper Rad, and Carolee Schneemann, among others, as well as newly preserved early video works by key figures such as Vito Acconci, Ant Farm and Tony Oursler. We are also introducing two new documentaries on the seminal earthworks and land art pieces of Robert Smithson, one of the most influential artists of the 20th century. We are also pleased to present several important series of video and film works. Point of View: An Anthology of the Moving Image features newly commissioned works by eleven major international artists, including Isaac Julien, William Kentridge and Pierre Huyghe; From the Kitchen Archives is a series of rare experimental performance documents from the 1970s and ‘80s; and Workshop of the Film Form is an anthology of early films by pioneers of the Polish moving- image avant-garde. -

Visual Arts Bachelor Ofartsin

Bachelor of Arts in Visual Arts 0918 WHAT DO STUDENTS LEARN? Students studying visual arts at Chatham choose between two concentrations: In the studio arts concentration, students are introduced to fundamental hands-on skills, processes, theory, history, and culture from foundation classes to contemporary visual theory and advanced studio practices such as ceramics, sculpture, painting, drawing, and printmaking. The art history concentration immerses students in trends and traditions of major art movements across the globe. Students analyze a wide range of art forms, from painting, sculpture, and architecture to photography, film, video, and electronic media, always grounded in its historical, theoretical, and cultural contexts. WHAT DO GRADUATES GO ON TO DO? Graduates of our studio arts concentration possess skills, foundations, and theoretical direction to navigate the creative industry in pursuit of such jobs as master printer, art handler, curator, museum professional, art registrar, art critic, or entrepreneur. Additionally, students within the studio arts concentration are prepared for graduate programs, artist residencies, and exhibition opportunities. Chatham students have entered competitive graduate programs in art history, museum studies, and arts management, and worked as curators, educators, and in institutional advancement for internationally-recognized museums. Others have launched careers directly after graduating as curators and grant writers, managers for artists’ studios, or founders of community-oriented art organizations. Visual Arts Our visual arts program combines the advantages of a small school with the perks of being in a city with a vibrant arts scene, including traditional museums and experimental spaces. By majoring in visual arts, you will enjoy working in small, intimate classes with a dynamic faculty that is well recognized in the local, national, and international community, learning how to care for, research, critically analyze, and create works of art. -

John Thomas Robinette

John Thomas Robinette III [email protected] 917-586-9332 Collections Manager and Advisor Specialist on all aspects of collections management with an emphasis on private collections and foundations in Latin America Expertise Collections Management Art Storage Supervision Fluency in Spanish Art Shipping and Logistics TMS Database Proficiency International Network Art Handling Artwork Courier Condition Reporting Experience Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros, New York, NY Manager of Storage and Installation, 2013-Present Assistant Registrar, 2010-2013 - Manage diverse array of collections. - Manage 3 storage facilities globally. - Manage assistant registrar and interns. - Negotiate contracts with vendors. - Manage outgoing loan program. - Initiate climate control policy in sites globally. - Implemented digital condition reporting procedures. Association of Registrars and Collections Specialists (ARCS) Board Member, 2017-Present - Chair Marketing and Website Committees. - Host monthly Twitter chat on the collections management. - Planned seminar “Territorios Inexplorados” in Mexico City. Independent Art Handler, New York, NY 2003-2010 - Installed art in luxury residences nationally. - Installed, de-installed, and packed works in various galleries throughout New York. Blanton Museum of Art, Austin, TX Curatorial Assistant/Installation Technician, 2000-2003 - Researched texts for Latin American Art catalog. - Compiled bibliography of artists in the collection. - Developed and managed Latin American Department Filemaker Pro database. - Supported exhibition planning. - Installed and de-installed temporary exhibitions. Professional Activities - Presented “El Correo Universal” for ARMICE, Spain, 2018 - Co-planned ARCS Seminar, Mexico City, 2017. - Presented “El otro lado: retos de colecciones fuera del museo” at ARCS - in Mexico City, 2017. - Attended ARCS Conference, Vancouver, Canada, 2017. - Presented “Latin American Shipping Q & A” at ARCS Conference, 2017. -

Sophie Calle's Prenez Soin De Vous

Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature Volume 38 Issue 2 Self and Stuff: Accumulation in Article 3 Francophone Literature and Art 2014 Accumulation and Archives: Sophie Calle’s Prenez soin de vous Natalie Edwards The University of Adelaide, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, French and Francophone Literature Commons, and the Interdisciplinary Arts and Media Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Edwards, Natalie (2014) "Accumulation and Archives: Sophie Calle’s Prenez soin de vous," Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: Vol. 38: Iss. 2, Article 3. https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.1016 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Accumulation and Archives: Sophie Calle’s Prenez soin de vous Abstract French project artist Sophie Calle has become well-known for her iconoclastic performance art that blends visual and textual elements. Beginning with Les Dormeurs in 1979, in which she invited 24 strangers to sleep in her empty bed and photographed them hourly, through her project of following people around Paris and photographing them like a private detective in Suite vénitienne, Calle has blurred the boundaries between private and public, between photographer and photographed, and between viewer and participant. In this article, I focus on her recent exhibition, Prenez soin de vous. -

New Practices, New Pedagogies

INNOVATIONS IN ART AND DESIGN NEW PRACTICES NEW PEDAGOGIES a reader EDITED BY MALCOLM MILES SWETS & ZEITLINGER / TAYLOR & FRANCIS GROUP 2004 Printed in Copyright © 2004 …… All rights reserved. No part of this publication of the information contained herein may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, by photocopying, recording or otherwise, without written prior permission from the publishers. Although all care is taken to ensure the integrity and quality of this publication and the information herein, no responsibility is assumed by the publishers nor the authors for any damage to properly or persons as a result of operation or use of this publication and/or the information contained herein. www ISBN ISSN The European League of Institutes of the Arts - ELIA - is an independent organisation of approximately 350 major arts education and training institutions representing the subject disciplines of Architecture, Dance, Design, Media Arts, Fine Art, Music and Theatre from over 45 countries. ELIA represents deans, directors, administrators, artists, teachers and students in the arts in Europe. ELIA is very grateful for support from, among others, The European Community for the support in the budget line 'Support to organisations who promote European culture' and the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science Published by SWETS & ZEITLINGER / TAYLOR & FRANCIS GROUP 2004 Supported by the European Commission, Socrates Thematic Network ‘Innovation in higher arts education -

Motion and Time Based: a Question of the Body and Its Reflections As Gesture

Introduction to Art Making- Motion and Time Based: A question of the body and its reflections as gesture. ...material action is painting that has spread beyond the picture surface. The human body, a laid table or a room becomes the picture surface. Time is added to the dimension of the body and space. - "Material Action Manifesto," Otto Muhl, 1964 VIS 2 Winter 2016 When: Tuesday: 5:00 p.m. to 6:50 p.m. Where: CENTR 101 Professor: Ricardo Dominguez Email: [email protected] Office Hour: Mondays. 11:00 a.m. to Noon. Room: VAF Studio 551 (2nd Fl. Visual Art Facility) The body-as-gesture has a long history as a site of aesthetic experimentation and reflection. Art-as-gesture has almost always been anchored to the body, the body in time, the body in space and the leftovers of the body This class will focus on the history of these bodies-as-gestures in performance art. An additional objective for the course will be a focus on the question of documentation in order to understand its relationship to performance as an active frame/framing of reflection. We will look at modernist, contemporary and post-contemporary, contemporary work by Chris Burden, Ulay and Abramovic, Allen Kaprow, Vito Acconci, Coco Fusco, Faith Wilding, Anne Hamilton, William Pope L., Tehching Hsieh, Revered Billy, Nao Bustamante, Ana Mendieta, Cindy Sherman, Adrian Piper, Sophie Calle, Ron Athey, Patty Chang, James Luna, and the work of many other body artists/performance artists. Students will develop 1 performance action a week, for 5 weeks, for a total of 5 gestures/actions (during the first part of the class), individually or in collaboration with other students.