God and Other Agents in Hindu Monotheism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monism and Monotheism in Al-Ghaz Lı's Mishk T Al-Anw R

Monism and Monotheism in al-Ghaz�lı’s Mishk�t al-anw�r Alexander Treiger YALE UNIVERSITY It is appropriate to begin a study on the problem of Monism versus Monotheism in Abü ˘�mid al-Ghaz�lı’s (d. 505/1111) thought by juxtaposing two passages from his famous treatise Mishk�t al-anw�r (‘The Niche of Lights’) which is devoted to an interpretation of the Light Verse (Q. 24:35) and of the Veils ˘adıth (to be discussed below).1 As I will try to show, the two passages represent monistic and monotheistic perspectives respectively. For the purposes of the present study, the term ‘monism’ refers to the theory, put forward by al-Ghaz�lı in a number of contexts, that God is the only existent in existence and the world, considered in itself, is ‘sheer non-existence’ (fiadam ma˛∂); while ‘monotheism’ refers to the view that God is the one of the totality of existents which is the source of existence for the rest of existents. The fundamental difference between the two views lies in their respective assessments of God’s granting existence to what is other than He: the monistic paradigm views the granting of existence as essentially virtual so that in the last analysis God alone exists, whereas the monotheistic paradigm sees the granting of existence as real.2 Let us now turn to the passages in question. Passage A: Mishk�t, Part 1, §§52–43 [§52] The entire world is permeated by external visual and internal intellectual lights … Lower [lights] emanate from one another the way light emanates from a lamp [sir�j, cf. -

JOSHUA L. MOSS Source: Melilah: Atheism, Scepticism and Challenges to Mono

EDITOR Daniel R. Langton ASSISTANT EDITOR Simon Mayers Title: Satire, Monotheism and Scepticism Author(s): JOSHUA L. MOSS Source: Melilah: Atheism, Scepticism and Challenges to Monotheism, Vol. 12 (2015), pp. 14-21 Published by: University of Manchester and Gorgias Press URL: http://www.melilahjournal.org/p/2015.html ISBN: 978-1-4632-0622-2 ISSN: 1759-1953 A publication of the Centre for Jewish Studies, University of Manchester, United Kingdom. Co-published by SATIRE, MONOTHEISM AND SCEPTICISM Joshua L. Moss* ABSTRACT: The habits of mind which gave Israel’s ancestors cause to doubt the existence of the pagan deities sometimes lead their descendants to doubt the existence of any personal God, however conceived. Monotheism was and is a powerful form of Scepticism. The Hebrew Bible contains notable satires of Paganism, such as Psalm 115 and Isaiah 44 with their biting mockery of idols. Elijah challenged the worshippers of Ba’al to a demonstration of divine power, using satire. The reader knows that nothing will happen in response to the cries of Baal’s worshippers, and laughs. Yet, the worshippers of Israel’s God must also be aware that their own cries for help often go unanswered. The insight that caused Abraham to smash the idols in his father’s shop also shakes the altar erected by Elijah. Doubt, once unleashed, is not easily contained. Scepticism is a natural part of the Jewish experience. In the middle ages Jews were non-believers and dissenters as far as the dominant religions were concerned. With the advent of modernity, those sceptical habits of mind could be applied to religion generally, including Judaism. -

Hinduism and Hindu Philosophy

Essays on Indian Philosophy UNIVE'aSITY OF HAWAII Uf,FU:{ Essays on Indian Philosophy SHRI KRISHNA SAKSENA UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII PRESS HONOLULU 1970 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 78·114209 Standard Book Number 87022-726-2 Copyright © 1970 by University of Hawaii Press All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America Contents The Story of Indian Philosophy 3 Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy 18 Testimony in Indian Philosophy 24 Hinduism 37 Hinduism and Hindu Philosophy 51 The Jain Religion 54 Some Riddles in the Behavior of Gods and Sages in the Epics and the Puranas 64 Autobiography of a Yogi 71 Jainism 73 Svapramanatva and Svapraka!;>atva: An Inconsistency in Kumarila's Philosophy 77 The Nature of Buddhi according to Sankhya-Yoga 82 The Individual in Social Thought and Practice in India 88 Professor Zaehner and the Comparison of Religions 102 A Comparison between the Eastern and Western Portraits of Man in Our Time 117 Acknowledgments The author wishes to make the following acknowledgments for permission to reprint previously published essays: "The Story of Indian Philosophy," in A History of Philosophical Systems. edited by Vergilius Ferm. New York:The Philosophical Library, 1950. "Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy," previously published as "Are There Any Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy?" in The Philosophical Quarterly. "Testimony in Indian Philosophy," previously published as "Authority in Indian Philosophy," in Ph ilosophyEast and West. vo!.l,no. 3 (October 1951). "Hinduism," in Studium Generale. no. 10 (1962). "The Jain Religion," previously published as "Jainism," in Religion in the Twentieth Century. edited by Vergilius Ferm. -

'ONE' in EGYPTIAN THEOLOGY Jan ASSMANN* That We May Speak Of

MONO-, PAN-, AND COSMOTHEISM: THINKING THE 'ONE' IN EGYPTIAN THEOLOGY Jan ASSMANN* That we may speak of Egyptian 'theology' is everything but self-evident. Theology is not something to be expected in every religion, not even in the Old Testament. In Germany and perhaps also elsewhere, there is a heated debate going on in OT studies about whether the subject of the discipline should be defined in the traditional way as "theology of OT" or rather, "history of Israelite religion".(1) The concern with questions of theology, some people argue, is typical only of Early Christianity when self-definitions and clear-cut concepts were needed in order to keep clear of Judaism, Gnosticism and all kinds of sects and heresies in between. Theology is a historical and rather exceptional phenomenon that must not be generalized and thoughtlessly projected onto other religions.(2) If theology is a contested notion even with respect to the OT, how much more so should this term be avoided with regard to ancient Egypt! The aim of my lecture is to show that this is not to be regarded as the last word about ancient Egyptian religion but that, on the contrary, we are perfectly justified in speaking of Egyptian theology. This seemingly paradoxical fact is due to one single exceptional person or event, namely to Akhanyati/Akhenaten and his religious revolution. Before I deal with this event, however, I would like to start with some general reflections about the concept of 'theology' and the historical conditions for the emergence and development of phenomena that might be subsumed under that term. -

Original Monotheism: a Signal of Transcendence Challenging

Liberty University Original Monotheism: A Signal of Transcendence Challenging Naturalism and New Ageism A Thesis Project Report Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Divinity in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Ministry Department of Christian Leadership and Church Ministries by Daniel R. Cote Lynchburg, Virginia April 5, 2020 Copyright © 2020 by Daniel R. Cote All Rights Reserved ii Liberty University School of Divinity Thesis Project Approval Sheet Dr. T. Michael Christ Adjunct Faculty School of Divinity Dr. Phil Gifford Adjunct Faculty School of Divinity iii THE DOCTOR OF MINISTRY THESIS PROJECT ABSTRACT Daniel R. Cote Liberty University School of Divinity, 2020 Mentor: Dr. T. Michael Christ Where once in America, belief in Christian theism was shared by a large majority of the population, over the last 70 years belief in Christian theism has significantly eroded. From 1948 to 2018, the percent of Americans identifying as Catholic or Christians dropped from 91 percent to 67 percent, with virtually all the drop coming from protestant denominations.1 Naturalism and new ageism increasingly provide alternative means for understanding existential reality without the moral imperatives and the belief in the divine associated with Christian theism. The ironic aspect of the shifting of worldviews underway in western culture is that it continues with little regard for strong evidence for the truth of Christian theism emerging from historical, cultural, and scientific research. One reality long overlooked in this regard is the research of Wilhelm Schmidt and others, which indicates that the earliest religion of humanity is monotheism. Original monotheism is a strong indicator of the existence of a transcendent God who revealed Himself as portrayed in Genesis 1-11, thus affirming the truth of essential elements of Christian theism and the falsity of naturalism and new ageism. -

PLUTARCH and “PAGAN MONOTHEISM” Frederick E. Brenk

PLUTARCH AND “PAGAN MONOTHEISM” Frederick E. Brenk When the Georgian poet, Rustaveli, visited Jerusa- lem in 1192, he recorded seeing on the frescoes of the Monastery of the Holy Cross, alongside Chris- tian saints, portraits of the Greek sages “such as Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Cheilon, Thucydides, and Plutarch, just as they are to be found in our monastery on Athos”.1 One of the great religious and philosophical aspects of late antiquity was monotheism.2 In the second century the only really well-known monothe- istic religious groups were the Jews and Christians. Jews and Judaism were 1 S. Brock, “A Syriac Collection of Prophecies of the Pagan Philosophers”, in S. Brock, Studies in Syriac Christianity. History, Literature and Theology (Hampshire 1992) ch. VII (origi- nally OLP 14 [1983] 203–246 at 203). 2 See G. Fowden, Empire to Commonwealth. Consequences of Monotheism in Late Antiq- uity (Princeton 1993); P. Athanassiadi & M. Frede (eds), Pagan Monotheism in Late Antiquity (Oxford 1999) and the review by M. Edwards, JThS 51 (2000) 339–342; R. Bloch, “Monotheism”, in Brill’s New Pauly, IX (2006) cols 171–174; C. Ando “Introduction to Part IV”, in idem (ed.), Roman Religion (Edinburgh 2003) 141–146; L.W. Hurtado, One God, One Lord. Early Christian Devotion and Ancient Jewish Monotheism (Philadelphia 2003); J. Assmann, “Monotheism and Polytheism”, in S. Iles Johnston (ed.), Religions of the Ancient World (Cambridge 2004) 17–31; M. Edwards, “Pagan and Christian Monotheism in the Age of Constantine”, in S. Swain & M. Edwards (eds), Approaching Late Antiquity. The Transformation from Early to Late Empire (Oxford 2004) 211–234; M. -

Are Jews the Only True Monotheists? Some Critical Reflections in Jewish Thought from the Renaissance to the Present

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (History) Department of History 2015 Are Jews the Only True Monotheists? Some Critical Reflections in Jewish Thought from the Renaissance to the Present David B. Ruderman University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/history_papers Part of the History of Religion Commons, Intellectual History Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Ruderman, D. B. (2015). Are Jews the Only True Monotheists? Some Critical Reflections in Jewish Thought from the Renaissance to the Present. Melilah: Manchester Journal of Jewish Studies, 12 22-30. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/history_papers/39 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/history_papers/39 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Are Jews the Only True Monotheists? Some Critical Reflections in Jewish Thought from the Renaissance to the Present Abstract Monotheism, by simple definition, implies a belief in one God for all peoples, not for one particular nation. But as the Shemah prayer recalls, God spoke exclusively to Israel in insisting that God is one. This address came to define the essential nature of the Jewish faith, setting it apart from all other faiths both in the pre-modern and modern worlds. This essay explores the positions of a variety of thinkers on the question of the exclusive status of monotheism in Judaism from the Renaissance until the present day. It first discusses the challenge offered to Judaism by the Renaissance thinker Pico della Mirandola and his notion of ancient theology which claimed a common core of belief among all nations and cultures. -

Drawing from Mysticism in Monotheistic Religious Traditions to Inform Profound and Transformative Learning

112 Drawing from Mysticism in Monotheistic Religious Traditions To Inform Profound and Transformative Learning Michael Kroth1, Davin J. Carr-Chellman2, and Julia Mahfouz3 1University of Idaho--Boise, 2University of Dayton, and 3University of Colorado-Denver Abstract: The purpose of this paper is to introduce the processes and practices of mysticism found within the monotheistic traditions, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, in an attempt to identify areas where these might inform, elaborate, and deepen our understanding of profound and transformative learning theory and practice. Keywords: monotheism, mysticism, profound learning, transformative learning theory “Mysticism has been called ‘the great spiritual current which goes through all religions.’” ~Annemarie Schimmel (2011, p. 4) The purpose of this paper is to introduce the processes and practices of mysticism within the monotheistic understandings of mysticism in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam in an attempt to identify areas where these might inform, elaborate, and deepen our understanding of profound and transformative learning theory and practice. This article will briefly propose: 1) connections between mysticism, profound and transformative learning; and 2) examine the underpinnings of mysticism as both an experience and a process to inform transformational and profound learning theory. For this initial discussion, we have primarily drawn from some of the key texts and thinkers which have interpreted mysticism from the perspectives of Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. By examining mysticism through three examples from monotheistic religions, this paper suggests that mysticism as an experience and process is strongly linked with profound and transformational learning and could be used to unpack ideas of transformative learning and also to help explicate the relationship of profound learning to transformative learning. -

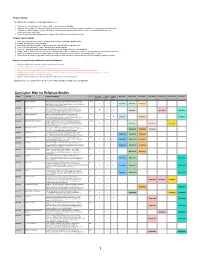

View the Curriculum

Program Mission The Mission of the Department of Religious Studies is to: 1. Introduce the methodologies of religious studies as an academic discipline 2. Advance the profession of religious studies through a commitment to scholarly research, publication, interpretation, and discussion 3. Cultivate an understanding of religious pluralism, including non-religious perspectives, in order to create global citizens in a religiously diverse world, and 4. Promote informed public dialogue about religion and its influence on society and culture. Program Learning Goals 1. Develop religious literacy in order for students to become responsible global citizens 2. Engage students in their own learning 3. Encourage students to analyze religion through the lenses of different world views 4. Connect theory and practice using examples from world religions 5. Challenge student presuppositions and ask students to reflect upon their inherited traditions 6. Analyze written, visual, or performed texts in religious studies with sensitivity to their diverse cultural contexts and historical moments 7. Argue from multiple perspectives about issues in religious studies that have both personal and global relevance 8. Demonstrate the ability to approach complex problems and ask complex questions drawing upon knowledge of religious studies Degree Learning Outcomes/Student Learning Outcomes 1. Clarify the difference between religious studies and theology 2. Contextualize religious phenomena 3. Use logic and theoretical methods to analyze religious issues and solve problems 4. Argue from multiple perspectives about issues in religious studies that have personal and global relevance 5. Demonstrate the ability to approach complex problems and ask complex questions drawing upon knowledge of religions 6. Communicate answers to real world problems 7. -

A Comparative Study of the Concept of God in Hinduism and Islam

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 3, Issue 2, February 2013 1 ISSN 2250-3153 A comparative study of the concept of God in Hinduism and Islam Abid Mushtaq Wani Abstract: In this research paper we will discuss the concept of God in Hinduism and Islam, the two major world religions. The theme of this paper is to show that monotheism is at the core of both these great religions. Islam is strictly monotheistic but Hinduism has pantheistic and henotheistic tendencies as well. While monotheism means the oneness and transcendence of God pantheism means that the Supreme Being is immanent in His creation and is present everywhere and in everything. Henotheism is the belief in one Supreme Divinity with the belief in other lesser deities. I. INTRODUCTION he concept of God is the basic tenet of almost all religions. I said almost because renowned religions like Buddhism and Jainism T do not hold the belief in an Absolute Creator of the world. Theologians usually define God as all-powerful, all-knowing, transcendent, eternal and infinite. My research paper is about the concept of God in one of the two major world religions of the world; Hinduism and Islam. We shall hypothesize that the unity of God is the central part of both these great religions. While Hinduism is pantheistic when Vedanta is taken into consideration, Islam is purely monotheistic. Most of the Hindus worship many gods and goddesses but they believe that they are the manifestations of One Absolute Being. I have consulted the basic sources of both these religions. -

Understanding in the Study of Bengal Renaissance Philosophical Thought1

Studia Religiologica 50 (4) 2017, s. 321–334 doi:10.4467/20844077SR.17.020.8461 www.ejournals.eu/Studia-Religiologica Phenomena of Religious Consciousness in the Genesis of Neo-Vedantism: Understanding in the Study of Bengal Renaissance Philosophical Thought1 Tatiana G. Skorokhodova Penza State University [email protected] Abstract The influences of the phenomena of religious consciousness on the thinking and philosophy of Modern India are described in the article, based on the Bengal Renaissance works of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, especially those of the inaugurator Rammohun Roy. He created the basic foundations of Neo-Vedanta philosophy predominantly owing to the special phenomena of re- ligious consciousness. The basic phenomena are primordial religious experience and the experience of contemplation and understanding of an Other religion (Islam and Christianity). Derivative phe- nomena are “monotheistic revolution” (term by G. Pomerants) and dialogue of religions in personal consciousness. Opening the resemblance of Vedanta and other religious traditions’ meanings to dialogue helped to achieve a new interpretation of the darśana. The novelty of Neo-Vedantism lies in the appearance of mighty ethical and social vectors of thinking. The combination of the aforesaid phenomena created the method of philosophising – free dialogue between one’s own tradition and another in order to enrich indigenous thought. Keywords: Vedanta, Neo-Vedantism, the Bengal Renaissance, Rammohun Roy, religious con- sciousness, understanding of other religion, dialogue Słowa kluczowe: Wedanta, Neowedanta, bengalski renesans, Rammohun Roy, świadomość religij na, zrozumienie innej religii, dialog The influence of religion on the genesis and development of modern Indian philoso- phy in the nineteenth and early twentieth century is a significant theme in research. -

PHILOSOPHIZING MONOTHEISM a Workshop in Philosophy and Theology ABSTRACTS

SCHOOL OF PHILOSOPHY – UNIVERSITY COLLEGE DUBLIN PHILOSOPHIZING MONOTHEISM A Workshop in Philosophy and Theology ABSTRACTS Wednesday, 10th May 2017 10h – 18h SPEAKERS Itzhak Benyamini Ward Blanton Joseph Cohen Aubrey Glazer Maureen Junker-Kenny Elad Lapidot Mahdi Tourage Raphael Zagury-Orly Coordinated by Itzhak Benyamini and Joseph Cohen 1 ABSTRACTS Three Modalities of Philosophizing Monotheism: Sacrifice, Election, Justice Joseph Cohen, University College Dublin, Ireland Raphael Zagury-Orly, Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, Jerusalem, Israel Our first question shall be: according to which modality are we to think the rapport between philosophy and monotheism? Indeed, this rapport has always been, in and throughout the history of Western thought, a complex one. From mutual exclusion to the efforts of synthesizing or conciliating both in one unifying discourse, to the numerous projects where one seeks to subjugate or contain the other, the alliance between philosophy and monotheism has never ceased to trouble philosophers and theologians alike. According to which idea and from which place can one maintain the singularities of both philosophical logos and monotheism whilst assuring the incontestable effects they both cause on each other? Undoubtedly, and in order to deploy our interpretative hypothesis, we will focus on the intricate dynamic between Judaism and Christianity and how this dynamic has surged in the history of philosophical thought. Consequently, our interpretative gesture will consist in developing three ideas – sacrifice, election, justice – by which is opened a certain address of both philosophical logos and monotheism. This address will show how and why both philosophical logos and monotheism incessantly read one into the other, inform and awaken each other whilst, at the same time, always fail to seize, comprehend or understand the singularity of the other.