Monotheism Polytheism Atheism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monism and Monotheism in Al-Ghaz Lı's Mishk T Al-Anw R

Monism and Monotheism in al-Ghaz�lı’s Mishk�t al-anw�r Alexander Treiger YALE UNIVERSITY It is appropriate to begin a study on the problem of Monism versus Monotheism in Abü ˘�mid al-Ghaz�lı’s (d. 505/1111) thought by juxtaposing two passages from his famous treatise Mishk�t al-anw�r (‘The Niche of Lights’) which is devoted to an interpretation of the Light Verse (Q. 24:35) and of the Veils ˘adıth (to be discussed below).1 As I will try to show, the two passages represent monistic and monotheistic perspectives respectively. For the purposes of the present study, the term ‘monism’ refers to the theory, put forward by al-Ghaz�lı in a number of contexts, that God is the only existent in existence and the world, considered in itself, is ‘sheer non-existence’ (fiadam ma˛∂); while ‘monotheism’ refers to the view that God is the one of the totality of existents which is the source of existence for the rest of existents. The fundamental difference between the two views lies in their respective assessments of God’s granting existence to what is other than He: the monistic paradigm views the granting of existence as essentially virtual so that in the last analysis God alone exists, whereas the monotheistic paradigm sees the granting of existence as real.2 Let us now turn to the passages in question. Passage A: Mishk�t, Part 1, §§52–43 [§52] The entire world is permeated by external visual and internal intellectual lights … Lower [lights] emanate from one another the way light emanates from a lamp [sir�j, cf. -

JOSHUA L. MOSS Source: Melilah: Atheism, Scepticism and Challenges to Mono

EDITOR Daniel R. Langton ASSISTANT EDITOR Simon Mayers Title: Satire, Monotheism and Scepticism Author(s): JOSHUA L. MOSS Source: Melilah: Atheism, Scepticism and Challenges to Monotheism, Vol. 12 (2015), pp. 14-21 Published by: University of Manchester and Gorgias Press URL: http://www.melilahjournal.org/p/2015.html ISBN: 978-1-4632-0622-2 ISSN: 1759-1953 A publication of the Centre for Jewish Studies, University of Manchester, United Kingdom. Co-published by SATIRE, MONOTHEISM AND SCEPTICISM Joshua L. Moss* ABSTRACT: The habits of mind which gave Israel’s ancestors cause to doubt the existence of the pagan deities sometimes lead their descendants to doubt the existence of any personal God, however conceived. Monotheism was and is a powerful form of Scepticism. The Hebrew Bible contains notable satires of Paganism, such as Psalm 115 and Isaiah 44 with their biting mockery of idols. Elijah challenged the worshippers of Ba’al to a demonstration of divine power, using satire. The reader knows that nothing will happen in response to the cries of Baal’s worshippers, and laughs. Yet, the worshippers of Israel’s God must also be aware that their own cries for help often go unanswered. The insight that caused Abraham to smash the idols in his father’s shop also shakes the altar erected by Elijah. Doubt, once unleashed, is not easily contained. Scepticism is a natural part of the Jewish experience. In the middle ages Jews were non-believers and dissenters as far as the dominant religions were concerned. With the advent of modernity, those sceptical habits of mind could be applied to religion generally, including Judaism. -

Hinduism and Hindu Philosophy

Essays on Indian Philosophy UNIVE'aSITY OF HAWAII Uf,FU:{ Essays on Indian Philosophy SHRI KRISHNA SAKSENA UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII PRESS HONOLULU 1970 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 78·114209 Standard Book Number 87022-726-2 Copyright © 1970 by University of Hawaii Press All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America Contents The Story of Indian Philosophy 3 Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy 18 Testimony in Indian Philosophy 24 Hinduism 37 Hinduism and Hindu Philosophy 51 The Jain Religion 54 Some Riddles in the Behavior of Gods and Sages in the Epics and the Puranas 64 Autobiography of a Yogi 71 Jainism 73 Svapramanatva and Svapraka!;>atva: An Inconsistency in Kumarila's Philosophy 77 The Nature of Buddhi according to Sankhya-Yoga 82 The Individual in Social Thought and Practice in India 88 Professor Zaehner and the Comparison of Religions 102 A Comparison between the Eastern and Western Portraits of Man in Our Time 117 Acknowledgments The author wishes to make the following acknowledgments for permission to reprint previously published essays: "The Story of Indian Philosophy," in A History of Philosophical Systems. edited by Vergilius Ferm. New York:The Philosophical Library, 1950. "Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy," previously published as "Are There Any Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy?" in The Philosophical Quarterly. "Testimony in Indian Philosophy," previously published as "Authority in Indian Philosophy," in Ph ilosophyEast and West. vo!.l,no. 3 (October 1951). "Hinduism," in Studium Generale. no. 10 (1962). "The Jain Religion," previously published as "Jainism," in Religion in the Twentieth Century. edited by Vergilius Ferm. -

'ONE' in EGYPTIAN THEOLOGY Jan ASSMANN* That We May Speak Of

MONO-, PAN-, AND COSMOTHEISM: THINKING THE 'ONE' IN EGYPTIAN THEOLOGY Jan ASSMANN* That we may speak of Egyptian 'theology' is everything but self-evident. Theology is not something to be expected in every religion, not even in the Old Testament. In Germany and perhaps also elsewhere, there is a heated debate going on in OT studies about whether the subject of the discipline should be defined in the traditional way as "theology of OT" or rather, "history of Israelite religion".(1) The concern with questions of theology, some people argue, is typical only of Early Christianity when self-definitions and clear-cut concepts were needed in order to keep clear of Judaism, Gnosticism and all kinds of sects and heresies in between. Theology is a historical and rather exceptional phenomenon that must not be generalized and thoughtlessly projected onto other religions.(2) If theology is a contested notion even with respect to the OT, how much more so should this term be avoided with regard to ancient Egypt! The aim of my lecture is to show that this is not to be regarded as the last word about ancient Egyptian religion but that, on the contrary, we are perfectly justified in speaking of Egyptian theology. This seemingly paradoxical fact is due to one single exceptional person or event, namely to Akhanyati/Akhenaten and his religious revolution. Before I deal with this event, however, I would like to start with some general reflections about the concept of 'theology' and the historical conditions for the emergence and development of phenomena that might be subsumed under that term. -

Hindi Beliefs: from Monotheism to Polytheism

jocO quarterly, Vol.1, No.2. Winter 2014 Hindi Beliefs: From Monotheism to Polytheism Shohreh Javadi This article retrieved from the research project of “the interplay Ph. D in Art history, University of Tehran of Indian and Iranian Art” and a field research trip, which was organized in 2012 by NAZAR research center. [email protected] Abstract Religious culture was out of access for Indian public, and deep philosophical religious texts were exclusively for the class of privileged and clergymen; So over many years, popular religion was collected in a book called Veda (means the Indian knowledge) including poems, legends and mystical chants which sometimes were obscure. This set is known as the world's oldest religious book and the mother of religions. Most researchers do not re- member it as a religion, and consider it as culture and rituals of living. Religion, ritual and popular beliefs in India were accompanied with the fabulous ambiguous curious adventures. What is understood from the appearance of Hindu ritual is polytheism, idolatry and superstition. But it is not true. The history of Hinduism and its branches expresses the monotheism and belief in the unity of the creator. As the Hindu-Iranian Aryans were always Unitarian and were praising various manifestations of nature as gods. They never were idolaters and believed in monotheism, although they had pluralistic beliefs. The interpretation of monotheistic in Semitic religions1 is different from Hinduism as a gradually altered religion. My field researches in India and dialogues with Hindu thinkers demonstrated that today’s common ritual in Hinduism is a distorted form of a monotheistic belief, that originally had believed in the Oneness of the Creator, as mentioned in the Upanishads. -

Original Monotheism: a Signal of Transcendence Challenging

Liberty University Original Monotheism: A Signal of Transcendence Challenging Naturalism and New Ageism A Thesis Project Report Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Divinity in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Ministry Department of Christian Leadership and Church Ministries by Daniel R. Cote Lynchburg, Virginia April 5, 2020 Copyright © 2020 by Daniel R. Cote All Rights Reserved ii Liberty University School of Divinity Thesis Project Approval Sheet Dr. T. Michael Christ Adjunct Faculty School of Divinity Dr. Phil Gifford Adjunct Faculty School of Divinity iii THE DOCTOR OF MINISTRY THESIS PROJECT ABSTRACT Daniel R. Cote Liberty University School of Divinity, 2020 Mentor: Dr. T. Michael Christ Where once in America, belief in Christian theism was shared by a large majority of the population, over the last 70 years belief in Christian theism has significantly eroded. From 1948 to 2018, the percent of Americans identifying as Catholic or Christians dropped from 91 percent to 67 percent, with virtually all the drop coming from protestant denominations.1 Naturalism and new ageism increasingly provide alternative means for understanding existential reality without the moral imperatives and the belief in the divine associated with Christian theism. The ironic aspect of the shifting of worldviews underway in western culture is that it continues with little regard for strong evidence for the truth of Christian theism emerging from historical, cultural, and scientific research. One reality long overlooked in this regard is the research of Wilhelm Schmidt and others, which indicates that the earliest religion of humanity is monotheism. Original monotheism is a strong indicator of the existence of a transcendent God who revealed Himself as portrayed in Genesis 1-11, thus affirming the truth of essential elements of Christian theism and the falsity of naturalism and new ageism. -

The Force of Monotheism. Psychoanalysis and Religions Thinking About Religion – After Freud Idea, Concept, Organization and De

The Force of Monotheism. Psychoanalysis and Religions Thinking About Religion – After Freud Idea, Concept, Organization and Design Inge Scholz-Strasser (Chairwoman, Sigmund Freud Foundation) Wolfgang Müller-Funk (University Vienna) Felix de Mendelssohn (Sigmund Freud University) The title represents the two axes upon which the symposium is to be based: the newly awakened discussion of religion, and Freud’s critical ideas on the subject of religion. When we put Freud’s monotheism in the foreground, then we are following a trail in his thinking. The psychoanalytic “lawgiver” and the Jewish Nomothet stand in a tense relationship to one another, but also in a relationship of analogy. Even if the line of delineation between psychoanalysis and the West’s Judeo-Christian heritage is meticulously drawn, it cannot be denied that Freud’s psychoanalysis, rooted in the skeptical tradition of the Enlightenment, is very distant from any sort of heterogeneous polytheism. Despite the occasional postmodern conjuring of a polytheistic mythology, which allegedly would be more tolerant on account of its diversity, no return of polytheism in religion is visible. The power of religion represents itself in ONE principle and it continues to be based in the singular. Since the Enlightenment and the critique of religion it initiated, an end of religion has seemed to represent a highly probable historical development. Exposed as deception, decried as an opium, dismissed as inadequate and outdated knowledge, religion has come to occupy an uncertain position. From this perspective it stands for the opposite of a consciousness that understands itself as enlightened. In this pattern of thinking, those who continue to have religion are easily seen as being inferior, backward, peripheral, uneducated, poor and maybe even female. -

PLUTARCH and “PAGAN MONOTHEISM” Frederick E. Brenk

PLUTARCH AND “PAGAN MONOTHEISM” Frederick E. Brenk When the Georgian poet, Rustaveli, visited Jerusa- lem in 1192, he recorded seeing on the frescoes of the Monastery of the Holy Cross, alongside Chris- tian saints, portraits of the Greek sages “such as Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Cheilon, Thucydides, and Plutarch, just as they are to be found in our monastery on Athos”.1 One of the great religious and philosophical aspects of late antiquity was monotheism.2 In the second century the only really well-known monothe- istic religious groups were the Jews and Christians. Jews and Judaism were 1 S. Brock, “A Syriac Collection of Prophecies of the Pagan Philosophers”, in S. Brock, Studies in Syriac Christianity. History, Literature and Theology (Hampshire 1992) ch. VII (origi- nally OLP 14 [1983] 203–246 at 203). 2 See G. Fowden, Empire to Commonwealth. Consequences of Monotheism in Late Antiq- uity (Princeton 1993); P. Athanassiadi & M. Frede (eds), Pagan Monotheism in Late Antiquity (Oxford 1999) and the review by M. Edwards, JThS 51 (2000) 339–342; R. Bloch, “Monotheism”, in Brill’s New Pauly, IX (2006) cols 171–174; C. Ando “Introduction to Part IV”, in idem (ed.), Roman Religion (Edinburgh 2003) 141–146; L.W. Hurtado, One God, One Lord. Early Christian Devotion and Ancient Jewish Monotheism (Philadelphia 2003); J. Assmann, “Monotheism and Polytheism”, in S. Iles Johnston (ed.), Religions of the Ancient World (Cambridge 2004) 17–31; M. Edwards, “Pagan and Christian Monotheism in the Age of Constantine”, in S. Swain & M. Edwards (eds), Approaching Late Antiquity. The Transformation from Early to Late Empire (Oxford 2004) 211–234; M. -

Are Jews the Only True Monotheists? Some Critical Reflections in Jewish Thought from the Renaissance to the Present

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (History) Department of History 2015 Are Jews the Only True Monotheists? Some Critical Reflections in Jewish Thought from the Renaissance to the Present David B. Ruderman University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/history_papers Part of the History of Religion Commons, Intellectual History Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Ruderman, D. B. (2015). Are Jews the Only True Monotheists? Some Critical Reflections in Jewish Thought from the Renaissance to the Present. Melilah: Manchester Journal of Jewish Studies, 12 22-30. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/history_papers/39 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/history_papers/39 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Are Jews the Only True Monotheists? Some Critical Reflections in Jewish Thought from the Renaissance to the Present Abstract Monotheism, by simple definition, implies a belief in one God for all peoples, not for one particular nation. But as the Shemah prayer recalls, God spoke exclusively to Israel in insisting that God is one. This address came to define the essential nature of the Jewish faith, setting it apart from all other faiths both in the pre-modern and modern worlds. This essay explores the positions of a variety of thinkers on the question of the exclusive status of monotheism in Judaism from the Renaissance until the present day. It first discusses the challenge offered to Judaism by the Renaissance thinker Pico della Mirandola and his notion of ancient theology which claimed a common core of belief among all nations and cultures. -

Drawing from Mysticism in Monotheistic Religious Traditions to Inform Profound and Transformative Learning

112 Drawing from Mysticism in Monotheistic Religious Traditions To Inform Profound and Transformative Learning Michael Kroth1, Davin J. Carr-Chellman2, and Julia Mahfouz3 1University of Idaho--Boise, 2University of Dayton, and 3University of Colorado-Denver Abstract: The purpose of this paper is to introduce the processes and practices of mysticism found within the monotheistic traditions, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, in an attempt to identify areas where these might inform, elaborate, and deepen our understanding of profound and transformative learning theory and practice. Keywords: monotheism, mysticism, profound learning, transformative learning theory “Mysticism has been called ‘the great spiritual current which goes through all religions.’” ~Annemarie Schimmel (2011, p. 4) The purpose of this paper is to introduce the processes and practices of mysticism within the monotheistic understandings of mysticism in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam in an attempt to identify areas where these might inform, elaborate, and deepen our understanding of profound and transformative learning theory and practice. This article will briefly propose: 1) connections between mysticism, profound and transformative learning; and 2) examine the underpinnings of mysticism as both an experience and a process to inform transformational and profound learning theory. For this initial discussion, we have primarily drawn from some of the key texts and thinkers which have interpreted mysticism from the perspectives of Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. By examining mysticism through three examples from monotheistic religions, this paper suggests that mysticism as an experience and process is strongly linked with profound and transformational learning and could be used to unpack ideas of transformative learning and also to help explicate the relationship of profound learning to transformative learning. -

Fundamentalist Religious Movements : a Case Study of the Maitatsine Movement in Nigeria

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2004 Fundamentalist religious movements : a case study of the Maitatsine movement in Nigeria. Katarzyna Z. Skuratowicz University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Skuratowicz, Katarzyna Z., "Fundamentalist religious movements : a case study of the Maitatsine movement in Nigeria." (2004). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1340. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1340 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FUNDAMENTALIST RELIGIOUS MOVEMENTS: A CASE STUDY OF THE MAITATSINE MOVEMENT IN NIGERIA By Katarzyna Z. Skuratowicz M.S, University of Warsaw, 2002 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Sociology University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2004 FUNDAMENTALIST RELIGIOUS MOVEMENTS: A CASE STUDY OF THE MAITATSINE MOVEMENT IN NIGERIA By Katarzyna Z. Skuratowicz M.S., University of Warsaw, Poland, 2002 A Thesis Approved on April 20, 2004 By the Following Thesis Committee: Thesis Director Dr. Lateef Badru University of Louisville Thesis Associate Dr. Clarence Talley University of Louisville Thesis Associate Dr. -

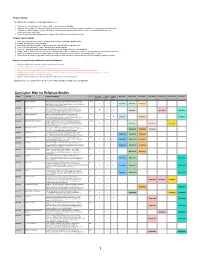

View the Curriculum

Program Mission The Mission of the Department of Religious Studies is to: 1. Introduce the methodologies of religious studies as an academic discipline 2. Advance the profession of religious studies through a commitment to scholarly research, publication, interpretation, and discussion 3. Cultivate an understanding of religious pluralism, including non-religious perspectives, in order to create global citizens in a religiously diverse world, and 4. Promote informed public dialogue about religion and its influence on society and culture. Program Learning Goals 1. Develop religious literacy in order for students to become responsible global citizens 2. Engage students in their own learning 3. Encourage students to analyze religion through the lenses of different world views 4. Connect theory and practice using examples from world religions 5. Challenge student presuppositions and ask students to reflect upon their inherited traditions 6. Analyze written, visual, or performed texts in religious studies with sensitivity to their diverse cultural contexts and historical moments 7. Argue from multiple perspectives about issues in religious studies that have both personal and global relevance 8. Demonstrate the ability to approach complex problems and ask complex questions drawing upon knowledge of religious studies Degree Learning Outcomes/Student Learning Outcomes 1. Clarify the difference between religious studies and theology 2. Contextualize religious phenomena 3. Use logic and theoretical methods to analyze religious issues and solve problems 4. Argue from multiple perspectives about issues in religious studies that have personal and global relevance 5. Demonstrate the ability to approach complex problems and ask complex questions drawing upon knowledge of religions 6. Communicate answers to real world problems 7.