Hong Kong: the Rise and Fall of “One Country, Two Systems”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016

Journal of US-China Public Administration, August 2016, Vol. 13, No. 8, 499-517 doi: 10.17265/1548-6591/2016.08.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016 Chung Fun Steven Hung The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong After direct elections were instituted in Hong Kong, politicization inevitably followed democratization. This paper intends to evaluate how political parties’ politics happened in Hong Kong’s recent history. The research was conducted through historical comparative analysis, with the context of Hong Kong during the sovereignty transition and the interim period of democratization being crucial. For the implementation of “one country, two systems”, political democratization was hindered and distinct political scenarios of Hong Kong’s transformation were made. The democratic forces had no alternative but to seek more radicalized politics, which caused a decisive fragmentation of the local political parties where the establishment camp was inevitable and the democratic blocs were split into many more small groups individually. It is harmful. It is not conducive to unity and for the common interests of the publics. This paper explores and evaluates the political history of Hong Kong and the ways in which the limited democratization hinders the progress of Hong Kong’s transformation. Keywords: election politics, historical comparative, ruling, democratization The democratizing element of the Hong Kong political system was bounded within the Legislative Council under the principle of the separation of powers of the three governing branches, Executive, Legislative, and Judicial. Popular elections for the Hong Kong legislature were introduced and implemented for 25 years (1991-2016) and there were eight terms of general elections for the Legislative Council. -

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926 Hongkong Workers in an Anti-Imperialist Movement Robert JamesHorrocks Submitted in accordancewith the requirementsfor the degreeof PhD The University of Leeds Departmentof East Asian Studies October 1994 The candidateconfirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where referencehas been made to the work of others. 11 Abstract In this thesis, I study the Guangzhou-Hongkong strike of 1925-1926. My analysis differs from past studies' suggestions that the strike was a libertarian eruption of mass protest against British imperialism and the Hongkong Government, which, according to these studies, exploited and oppressed Chinese in Guangdong and Hongkong. I argue that a political party, the CCP, led, organised, and nurtured the strike. It centralised political power in its hands and tried to impose its revolutionary visions on those under its control. First, I describe how foreign trade enriched many people outside the state. I go on to describe how Chinese-run institutions governed Hongkong's increasingly settled non-elite Chinese population. I reject ideas that Hongkong's mixed-class unions exploited workers and suggest that revolutionaries failed to transform Hongkong society either before or during the strike. My thesis shows that the strike bureaucracy was an authoritarian power structure; the strike's unprecedented political demands reflected the CCP's revolutionary political platform, which was sometimes incompatible with the interests of Hongkong's unions. I suggestthat the revolutionary elite's goals were not identical to those of the unions it claimed to represent: Hongkong unions preserved their autonomy in the face of revolutionaries' attempts to control Hongkong workers. -

Modern Hong Kong

Modern Hong Kong Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History Modern Hong Kong Steve Tsang Subject: China, Hong Kong, Macao, and/or Taiwan Online Publication Date: Feb 2017 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.280 Abstract and Keywords Hong Kong entered its modern era when it became a British overseas territory in 1841. In its early years as a Crown Colony, it suffered from corruption and racial segregation but grew rapidly as a free port that supported trade with China. It took about two decades before Hong Kong established a genuinely independent judiciary and introduced the Cadet Scheme to select and train senior officials, which dramatically improved the quality of governance. Until the Pacific War (1941–1945), the colonial government focused its attention and resources on the small expatriate community and largely left the overwhelming majority of the population, the Chinese community, to manage themselves, through voluntary organizations such as the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals. The 1940s was a watershed decade in Hong Kong’s history. The fall of Hong Kong and other European colonies to the Japanese at the start of the Pacific War shattered the myth of the superiority of white men and the invincibility of the British Empire. When the war ended the British realized that they could not restore the status quo ante. They thus put an end to racial segregation, removed the glass ceiling that prevented a Chinese person from becoming a Cadet or Administrative Officer or rising to become the Senior Member of the Legislative or the Executive Council, and looked into the possibility of introducing municipal self-government. -

Hong Kong’S Summer of Protest

TABLE OF CONTENTS Video Summary & Related Content 3 Video Review 4 Before Viewing 5 While Viewing 6 Talk Prompts 8 After Viewing 12 The Story 14 ACTIVITY #1: Protest tactics 19 ACTIVITY #2: Types of Government 22 Sources 23 Video Review – While Viewing (Responses) 24 CREDITS News in Review is produced by Visit www.curio.ca/newsinreview for an archive CBC NEWS and curio.ca of all previous News In Review seasons. As a companion resource, go to www.cbc.ca/news GUIDE for additional articles. Writer/editor: Sean Dolan Additional editing: Michaël Elbaz CBC authorizes reproduction of material VIDEO contained in this guide for educational Host: Michael Serapio purposes. Please identify source. Senior Producer: Jordanna Lake News In Review is distributed by: Supervising Manager: Laraine Bone curio.ca | CBC Media Solutions © 2019 Canadian Broadcasting Corporation BATTLING BEIJING: Hong Kong’s Summer of Protest Video duration – 14:48 In the spring of 2019 Beijing announced an extradition bill that would have allowed Hong Kong residents to be extradited and tried in Communist mainland China. That led to growing protests demanding the withdrawal of the bill. Frustrations mounted and so did the use of force on both sides. As crowds grew into the millions, Chinese officials used tear gas, water canons and rubber bullets, eventually resorting to the threat of military intervention to quelch demonstrations. Thirteen weeks in and the citizens of Hong Kong remained steadfast. Then, on September 3rd the Beijing government bowed to the protestors' primary demand and the bill was withdrawn. But where that leaves Hong Kong now remains unclear. -

As Chinese Pressure on Taiwan Grows, Beijing Turns Away from Cross-Strait “Diplomatic Truce” Matthew Southerland, Policy Analyst, Security and Foreign Affairs

February 9, 2017 As Chinese Pressure on Taiwan Grows, Beijing Turns Away from Cross-Strait “Diplomatic Truce” Matthew Southerland, Policy Analyst, Security and Foreign Affairs A Return to “Poaching” Taiwan’s Diplomatic Partners? On December 21, 2016, Sao Tome and Principe—a country consisting of a group of islands and islets off the western coast of central Africa—broke diplomatic relations with Taiwan, and on December 26 re-established diplomatic relations with China.*1 This is the second time since the election of Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen† that China has re-established diplomatic relations with one of Taipei’s former diplomatic partners, marking a change in Beijing’s behavior. The first time was shortly before President Tsai’s inauguration in March 2016, when China re-established relations with The Gambia, which had severed ties with Taiwan more than two years before.‡ 2 In 2008, Taipei and Beijing reached a tacit understanding to stop using financial incentives to compete for recognition from each other’s diplomatic partners—a “diplomatic truce.”3 During the period that followed, Beijing also rejected overtures from several of Taiwan’s diplomatic partners to establish diplomatic relations with China.4 Beijing’s recent shift is one of the latest in a series of efforts to pressure the Tsai Administration. Despite President Tsai’s pragmatic approach to cross-Strait relations and attempts to compromise, Beijing views her with suspicion due to her unwillingness to endorse the “One China” framework§ for cross-Strait relations. Sao Tome’s decision to cut ties with Taipei appears to have been related—at least in part—to a request from Sao Tome for more aid.5 A statement released by Taiwan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs included the following: “The government of Sao Tome and Principe .. -

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration)

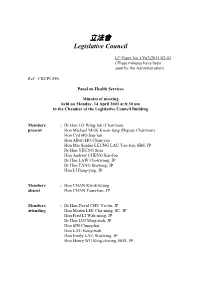

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(2)2011/02-03 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Ref : CB2/PL/HS Panel on Health Services Minutes of meeting held on Monday, 14 April 2003 at 8:30 am in the Chamber of the Legislative Council Building Members : Dr Hon LO Wing-lok (Chairman) present Hon Michael MAK Kwok-fung (Deputy Chairman) Hon Cyd HO Sau-lan Hon Albert HO Chun-yan Hon Mrs Sophie LEUNG LAU Yau-fun, SBS, JP Dr Hon YEUNG Sum Hon Andrew CHENG Kar-foo Dr Hon LAW Chi-kwong, JP Dr Hon TANG Siu-tong, JP Hon LI Fung-ying, JP Members : Hon CHAN Kwok-keung absent Hon CHAN Yuen-han, JP Members : Dr Hon David CHU Yu-lin, JP attending Hon Martin LEE Chu-ming, SC, JP Hon Fred LI Wah-ming, JP Dr Hon LUI Ming-wah, JP Hon SIN Chung-kai Hon LAU Kong-wah Hon Emily LAU Wai-hing, JP Hon Henry WU King-cheong, BBS, JP - 2 - Public Officers : Mr Thomas YIU, JP attending Deputy Secretary for Health, Welfare and Food Mr Nicholas CHAN Assistant Secretary for Health, Welfare and Food Dr P Y LAM, JP Deputy Director of Health Dr W M KO, JP Director (Professional Services & Public Affairs) Hospital Authority Dr Thomas TSANG Consultant Clerk in : Ms Doris CHAN attendance Chief Assistant Secretary (2) 4 Staff in : Ms Joanne MAK attendance Senior Assistant Secretary (2) 2 I. Confirmation of minutes (LC Paper No. CB(2)1735/02-03) The minutes of the regular meeting on 10 March 2003 were confirmed. -

I Am Sorry. Would Members Please Deal with One Piece of Business. It Is Now Eight O’Clock and Under Standing Order 8(2) This Council Should Now Adjourn

4920 HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ― 29 June 1994 8.00 pm PRESIDENT: I am sorry. Would Members please deal with one piece of business. It is now eight o’clock and under Standing Order 8(2) this Council should now adjourn. ATTORNEY GENERAL: Mr President, with your consent, I move that Standing Order 8(2) should be suspended so as to allow the Council’s business this evening to be concluded. Question proposed, put and agreed to. Council went into Committee. CHAIRMAN: Council is now in Committee and is suspended until 15 minutes to nine o’clock. 8.56 pm CHAIRMAN: Committee will now resume. MR MARTIN LEE (in Cantonese): Mr Chairman, thank you for adjourning the debate on my motion so that Members could have a supper break. I hope I can secure a greater chance of success if they listen to my speech after dining. Mr Chairman, on behalf of the United Democrats of Hong Kong (UDHK), I move the amendments to clause 22 except item 12 of schedule 2. The amendments have already been set out under my name in the paper circulated to Members. Mr Chairman, before I make my speech, I would like to raise a point concerning Mr Jimmy McGREGOR because he was quite upset when he heard my previous speech. He hoped that I could clarify one point. In fact, I did not mean that all the people in the commercial sector had not supported democracy. If all the voters in the commercial sector had not supported democracy, Mr Jimmy McGREGOR would not have been returned in the 1988 and 1991 elections. -

The Basic Law and Democratization in Hong Kong

THE BASIC LAW AND DEMOCRATIZATION IN HONG KONG Michael C. Davis† I. Introduction Hong Kong’s status as a Special Administrative Region of China has placed it on the foreign policy radar of most countries having relations with China and interests in Asia. This interest in Hong Kong has encouraged considerable inter- est in Hong Kong’s founding documents and their interpretation. Hong Kong’s constitution, the Hong Kong Basic Law (“Basic Law”), has sparked a number of debates over democratization and its pace. It is generally understood that greater democratization will mean greater autonomy and vice versa, less democracy means more control by Beijing. For this reason there is considerable interest in the politics of interpreting Hong Kong’s Basic Law across the political spectrum in Hong Kong, in Beijing and in many foreign capitals. This interest is en- couraged by appreciation of the fundamental role democratization plays in con- stitutionalism in any society. The dynamic interactions of local politics and Beijing and foreign interests produce the politics of constitutionalism in Hong Kong. Understanding the Hong Kong political reform debate is therefore impor- tant to understanding the emerging status of both Hong Kong and China. This paper considers the politics of constitutional interpretation in Hong Kong and its relationship to developing democracy and sustaining Hong Kong’s highly re- garded rule of law. The high level of popular support for democratic reform in Hong Kong is a central feature of the challenge Hong Kong poses for China. Popular Hong Kong values on democracy and human rights have challenged the often undemocratic stance of the Beijing government and its supporters. -

Discourse, Social Scales, and Epiphenomenality of Language Policy: a Case Study of a Local, Hong Kong NGO

Discourse, Social Scales, and Epiphenomenality of Language Policy: A Case Study of a Local, Hong Kong NGO Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Tso, Elizabeth Ann Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 12:25:43 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/623063 DISCOURSE, SOCIAL SCALES, AND EPIPHENOMENALITY OF LANGUAGE POLICY: A CASE STUDY OF A LOCAL, HONG KONG NGO by Elizabeth Ann Tso __________________________ Copyright © Elizabeth Ann Tso 2017 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the GRADUATE INTERDISCIPLINARY PROGRAM IN SECOND LANGUAGE ACQUISITION AND TEACHING In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2017 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Elizabeth Tso, titled Discourse, Social Scales, and Epiphenomenality of Language Policy: A Case Study of a Local, Hong Kong NGO, and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________________________ Date: (January 13, 2017) Perry Gilmore _______________________________________________ Date: (January 13, 2017) Wenhao Diao _______________________________________________ Date: (January 13, 2017) Sheilah Nicholas Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. -

The Chief Executive's 2020 Policy Address

The Chief Executive’s 2020 Policy Address Striving Ahead with Renewed Perseverance Contents Paragraph I. Foreword: Striving Ahead 1–3 II. Full Support of the Central Government 4–8 III. Upholding “One Country, Two Systems” 9–29 Staying True to Our Original Aspiration 9–10 Improving the Implementation of “One Country, Two Systems” 11–20 The Chief Executive’s Mission 11–13 Hong Kong National Security Law 14–17 National Flag, National Emblem and National Anthem 18 Oath-taking by Public Officers 19–20 Safeguarding the Rule of Law 21–24 Electoral Arrangements 25 Public Finance 26 Public Sector Reform 27–29 IV. Navigating through the Epidemic 30–35 Staying Vigilant in the Prolonged Fight against the Epidemic 30 Together, We Fight the Virus 31 Support of the Central Government 32 Adopting a Multi-pronged Approach 33–34 Sparing No Effort in Achieving “Zero Infection” 35 Paragraph V. New Impetus to the Economy 36–82 Economic Outlook 36 Development Strategy 37 The Mainland as Our Hinterland 38–40 Consolidating Hong Kong’s Status as an International Financial Centre 41–46 Maintaining Financial Stability and Striving for Development 41–42 Deepening Mutual Access between the Mainland and Hong Kong Financial Markets 43 Promoting Real Estate Investment Trusts in Hong Kong 44 Further Promoting the Development of Private Equity Funds 45 Family Office Business 46 Consolidating Hong Kong’s Status as an International Aviation Hub 47–49 Three-Runway System Development 47 Hong Kong-Zhuhai Airport Co-operation 48 Airport City 49 Developing Hong Kong into -

1 the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project DAVID HAMILTON SHINN Interviewed

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project DAVID HAMILTON SHINN Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: July 5, 2002 Copyright 2004 A ST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born and raised in akima, Washington George Washington University Entered Foreign Service - 1964 American Foreign Service Association [AFSA, Beirut, -e.anon - Rotation Officer 1964-1966 0onsular 1ork Environment State Department - FS2 - S1ahili -anguage Training 1966-1963 Nairo.i, 5enya - Political Officer 1963-1968 Seychelles U.S. naval visits 85ikuyu domination9 Environment British Ethnicities North1estern University - African Studies 1968-1969 State Department - East African Affairs 1969-1931 Ethiopia Eritrea State Department - East African Affairs - Tan:ania-Uganda Desk Officer 1931-1932 American assassinated Dar es Salaam, Tan:ania - Political Officer 1932-1934 Relations 1 Economy 0hinese Nouakchott, Mauritania - D0M 1934-1936 Polisario French Environment Seattle, Washington - Pearson Program 1936-19?? Municipal policy planning State Department - State and Municipal Governments -iaison 19??-1981 aounde, 0ameroon - D0M 1981-1983 0had border N?Djamena, 0had - TD - 0harge d?affaires 198? President Ha.re Security Mala.o, Equatorial Guinea aounde, 0ameroon Acontinued) 1981-1983 Am.assador Hume Horan Anglo vs. French relations 5hartoum, Sudan - D0M 1983-1986 USA2D Relations Nimeiri Southern Sudan Neigh.or policies Falasha transit 0oup U.S. interests British Security State Department - Senior Seminar 1986-1983 -

Bevir the Making of British Socialism.Indb

Copyrighted Material CHAPTER ONE Introduction: Socialism and History “We Are All Socialists Now: The Perils and Promise of the New Era of Big Government” ran the provocative cover of Newsweek on 11 Feb ruary 2009. A financial crisis had swept through the economy. Several small banks had failed. The state had intervened, pumping money into the economy, bailing out large banks and other failing financial institu tions, and taking shares and part ownership in what had been private companies. The cover of Newsweek showed a red hand clasping a blue one, implying that both sides of the political spectrum now agreed on the importance of such state action. Although socialism is making headlines again, there seems to be very little understanding of its nature and history. The identification of social ism with “big government” is, to say the least, misleading. It just is not the case that when big business staggers and the state steps in, you have socialism. Historically, socialists have often looked not to an enlarged state but to the withering away of the state and the rise of nongovern mental societies. Even when socialists have supported state intervention, they have generally focused more on promoting social justice than on simply bailing out failing financial institutions. A false identification of socialism with big government is a staple of dated ideological battles. The phrase “We are all socialists now” is a quo tation from a British Liberal politician of the late nineteenth century. Sir William Harcourt used it when a land reform was passed with general acceptance despite having been equally generally denounced a few years earlier as “socialist.” Moreover, Newsweek’s cover was not the first echo of Harcourt’s memorable phrase.