The Physical Tourist Geneva: from the Science of the Enlightenment to CERN*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Astronomy Department of the University of Geneva (UNIGE) and Its Exoplanet Team

Département D'Astronomie Chemin des Mailletess 5 Université De Genève CH-5290 Versoix Sauverny Switzerland +45 22 379 22 00 [email protected] www.unige.ch/sciences/astro/en/ The Astronomy Department of the University of Geneva (UNIGE) and its Exoplanet Team About the Astronomy Department The Department of Astronomy of the University of Geneva (UNIGE) is located on the commune of Versoixs 5 km from the Geneva city center. The main buidings (l’Observatoire) are in the forest on the site of Sauvernys km from the town of Versoix. Another sites Ecogias closer to town hosts most of our space developments. Grounded in 5772 as the Geneva Observatory the insttute became the Department of Astronomy of UNIGE in 5973. Todays a group of approximately 5 0 people are employeds including scientstss PhD candidatess studentss technical staf (computer and electronics specialistss mechanics)s as well as administratve staf. The Astronomy Department manages a permanent astronomical observaton statonn a 5s2 m telescope on the site of La Silla (ESOs Chile). Observatons are also regularly obtained with the other ESO facilitess from the 5.93m telescope on the site of St-Michel (Observatory of Haute Provences OHPs France)s and from La Palma (Canary Islandss Spain). Astronomy Department Research Overview Research in the Department of Astronomy is described according to the Roadmap for Astronomy in Switzerland 2007-2056 four main themesn Exoplanetary systems Stars formaton evoluton Galaxies Universe Extreme Universe Main Building of the Astronomy Department in Versoix/Geneva 5 Département D'Astronomie Chemin des Mailletess 5 Université De Genève CH-5290 Versoix Sauverny Switzerland +45 22 379 22 00 [email protected] www.unige.ch/sciences/astro/en/ Research at the Exoplanetary Group The discovery of planets orbitng other stars (exoplanets) has been one of the major breakthroughs in astronomy of the past decades. -

CV En Didier Queloz.Pdf

1 CURRICULUM VITAE Didier Queloz July 2012 Date of birth 23 February 1966 Nationality Swiss Current Position Professor, Geneva University, Geneva Observatory 51ch des Maillettes, CH-1290 Sauverny Switzerland Academic degrees 1990 Master in physics, Geneva University 1992 Astronomy and Astrophysics Certificate (DEA) 1995 PhD with Prof M. Mayor “Research by cross-correlation techniques”, Geneva University Awards § Science quotation (1995) for Discovery of the first extra-solar planet as on of the 10 most important discovery of the year § “Vacheron Constantin” prize (1996) for best phD of the Geneva science faculty § “Balzers” prize from the Swiss Physical Society (1996) for the discovery of the planet orbiting the star 51Peg § IAU Medal of honor (1996) commission 51 Bioastronomy § “Prix de la ville de Genève” 2011, Science category § BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Awards 2011 § Honorary degrees from Employments 1996-1997 Post-doc, Geneva University 1997-1999 Distinguished visiting scientist, Jet Propulsion Lab, CA, USA 2000-2002 Research associate (“maitre assistant”), Geneva University 2003-2007 Faculty (“MER”), Geneva University 2008 Professor (PAD), Geneva University Professional service and committees • ESA Scientific Advisory group for IRSI-DARWIN (1997-2001) • IAU “radial velocity commission” (1997-2006) 2 • Board of the science advisory councilors of the OHP (1997-2000) • Study science team for PRIMA (ESO) (1998-2000) • ESO Observation Program Committee (OPC) (ESO telescope allocation) (2000-2001) • ESA Astronomical Working -

A Three-Planet Extrasolar System

quires that common properties in all the Acknowledgements Koch A. et al. 2006a, The Messenger 123, 38 dSphs be identified – we must therefore Koch A. et al. 2006b, AJ 131, 895 Mark I. Wilkinson acknowledges the Particle Physics Majewski S. R. et al. 2005, AJ 130, 2677 carry out similar studies of all dSphs. and Astronomy Research Council of the United Martin N. et al. 2006, MNRAS 367, L69 Kingdom for financial support. Andreas Koch and Mateo M. et al. 1993, AJ 105, 510 Finally, in the area of dynamical model- Eva K. Grebel thank the Swiss National Science Mateo M. 1997, ASP Conf. Ser. 116, 259 ling, identifying correlations between the Foundation for financial support. Mateo M. et al. 1998, AJ 116, 2315 Monelli M. et al. 2003, AJ 126, 218 kinematics and abundances of the stel- Munoz R. R. et al. 2005, ApJ 631, L137 lar populations in dSphs (e.g. Tolstoy et References Shetrone M. D. et al. 2001, ApJ 548, 592 al. 2006) is likely to provide important Tolstoy E. et al. 2006, The Messenger 123, 33 new information about the formation and Aaronson M. 1983, ApJ 266, L11 Wilkinson M. I. et al. 2002, MNRAS 330, 778 Belokurov V. et al. 2006, ApJL, submitted, Wilkinson M. I. et al. 2004, MNRAS 611, L21 evolution of these objects, which in turn astro-ph/0604355 Wilkinson M. I. et al. 2006, in proceedings of XXIst will further constrain models of any astro- Goerdt T. et al. 2006, MNNRAS 368, 1073 IAP meeting, EDP sciences, astro-ph/0602186 physical feedback on their dark matter. -

Who Really Discovered the First Exoplanet?

Who Really Discovered the First Exoplanet? Two Swiss astronomers got a well-deserved Nobel for finding an exoplanet, but there’s an intriguing backstory By Josh Winn The year 1995, like 1492, was the dawn of an age of discovery. The new explorers, instead of using seagoing vessels to discover continents, use telescopes to discover planets revolving around distant stars. Thousands of these extrasolar planets, a term usually shortened to “exoplanets,” have been found, including a few potentially Earth- like worlds, along with bizarre objects that bear no resemblance to any of the planets in our solar system. Two of these exoplanet explorers, Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz, were recently awarded half of the Nobel Prize in Physics for the discovery they made in 1995. My colleagues and I are united in our admiration for their pioneering work, and in our pride to be continuing what they began. But there is something peculiar about the Nobel Prize citation. It says: “for the discovery of an exoplanet orbiting a solar-type star.” Shouldn’t it say the first exoplanet? After all, hundreds of astronomers have discovered an exoplanet. I’ve helped find a few. Even high school students and amateur astronomers have discovered them. Did the Nobel Committee make a typographical error? No, they did not, and thereby hangs a tale. Just as it is problematic to decide who discovered America (Christopher Columbus? John Cabot? Leif Erikson? Amerigo Vespucci, whose name is the one that stuck? Those who came on foot from Siberia tens of thousands of years ago?) it is difficult to say who discovered the first exoplanet. -

A Catalog of Rotational and Radial Velocities for Evolved Stars V

A&A 561, A126 (2014) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201220762 & c ESO 2014 Astrophysics A catalog of rotational and radial velocities for evolved stars V. Southern stars, J. R. De Medeiros1,S.Alves1,S.Udry2, J. Andersen3,4,B.Nordström3, and M. Mayor2 1 Departamento de Física, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Campus Universitário, 59072-970 Natal, RN, Brasil e-mail: [email protected] 2 Observatoire de Genève, Université de Genève, Chemin des Maillettes 51, 1290 Sauverny, Switzerland 3 The Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen, Juliane Maries Vej 30, 2100 Copenhagen, Denmark 4 Nordic Optical Telescope, Apartado 474, 38700 Santa Cruz de La Palma, Spain Received 19 November 2012 / Accepted 10 December 2013 ABSTRACT Rotational and radial velocities have been measured for 1589 evolved stars of spectral types F, G, and K and luminosity classes IV, III, II, and Ib, based on observations carried out with the CORAVEL spectrometers. The precision in radial velocity is better than 0.30 km s−1 per observation, whereas rotational velocity uncertainties are typically 1.0 km s−1 for subgiants and giants and 2.0 km s−1 for class II giants and Ib supergiants. Key words. stars: late-type – stars: fundamental parameters – binaries: spectroscopic – techniques: radial velocities – catalogs – stars: evolution 1. Introduction enabling reliable investigations of stellar rotational character- istics in different regions of the H−Rdiagram(Carlberg et al. Over the past two decades, observations have been carried out at 2011; Cortés et al. 2009; Melo et al. 2001), the relation- the Geneva Observatory, Switzerland, and the Federal University ship between rotation and different stellar properties (Monaco of Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil, to accurately measure projected v et al. -

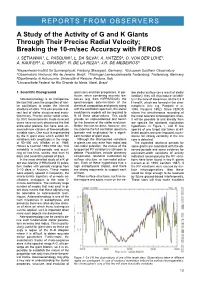

REPO RT SFROMOBSE RV ERSA Study of the Activity of G and K

R E P O RT S F R O M O B S E RV E R S A Study of the Activity of G and K Giants Through Their Precise Radial Velocity; Breaking the 10-m/sec Accuracy with FEROS J. SETIAWAN 1, L. PASQUINI 2, L. DA SILVA3, A. HATZES4, O. VON DER LÜHE1, A. KAUFER2, L. GIRARDI 5, R. DE LA REZA3, J.R. DE MEDEIROS6 1Kiepenheuer-Institut für Sonnenphysik, Freiburg (Breisgau), Germany; 2European Southern Observatory 3Observatorio Nacional, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; 4Thüringer Landessternwarte Tautenburg, Tautenburg, Germany 5Dipartimento di Astronomia, Università di Padova, Padova, Italy 6Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, Brazil 1. Scientific Background giant stars and their progenitors. In par- ible stellar surface (as a result of stellar ticular, when combining accurate dis- rotation), they will also induce variabili- Asteroseismology is an indispensa- tances (e.g. from HIPPARCOS), the ty in the core of deep lines, as the Ca II ble tool that uses the properties of stel- spectroscopic determination of the H and K, which are formed in the chro- lar oscillations to probe the internal chemical composition and gravity along mosphere (see e.g. Pasquini et al. structure of stars. This can provide a di- with the oscillation spectrum, the stellar 1988, Pasquini 1992). Since FEROS rect test of stellar structure and evolu- evolutionary models will be required to allows the simultaneous recording of tion theory. Precise stellar radial veloc- fit all these observations. This could the most relevant chromospheric lines, ity (RV) measurements made in recent provide an unprecedented test bench it will be possible to test directly from years have not only discovered the first for the theories of the stellar evolution. -

Dr. Avi Mandell (NASA) “Somewhere, Something Incredible Is Waiting to Be Known.” - Carl Sagan

The Age of Exoplanets: From First Discoveries to the Search for Living Worlds Dr. Avi Mandell (NASA) “Somewhere, something incredible is waiting to be known.” - Carl Sagan How will the discovery of a distant planet teeming with life change our perspective on our own planet – and on ourselves? Planets 101: Our Solar SysteM Planets 101: Our Solar SysteM First Planet Around a Sun-Like Star Discovered in 1995 Notable Facts About 1995: • Bill Clinton is in his 3rd year of the Presidency • Ebay opens for business •DVDs are first introduced •Big event for the coffee-drinking world… Invention of the Frappucino! The First Planets were Discovered by Measuring The Motions of Stars 51 Peg b • Uses the change in star’s light due to the Doppler effect Mayor & Queloz, Movie: eso1035g.mov November 1995 Dr. Michel Mayor & Dr. Didier Queloz Geneva Observatory Spectrum of Starlight from Dr. Geoff Marcy & Parent Star Dr. R. Paul Butler San Francisco State Univ. Timeline of Exoplanet Discoveries Known Exoplanets, 1995: 0 Planet Mass Jup. Neptune Earth Mercury Earth Jupiter Distance to the Star Timeline of Exoplanet Discoveries Known Exoplanets, 1996: 6 Planet Mass Jup. First Confirmed RV Planet: 51 Peg b Neptune Earth Mercury Earth Jupiter Distance to the Star Timeline of Exoplanet Discoveries Known Exoplanets, 1996: 6 2000: 38 Planet Mass First Transiting Planet: Jup. HD 209458 b First Confirmed RV Planet: 51 Peg b Neptune Earth Mercury Earth Jupiter Distance to the Star The Most Planets have been Discovered by Measuring The Shadows on Stars Movie: OccultationGraphH264FullSize.mov Timeline of Exoplanet Discoveries Known Exoplanets, 2000: 38 2005: 155 2008: 260 2012: 579 Planet Mass Jup. -

THE STELLAR VARIABILITY from HIPPARCOS PHOTOMETRY M. GRENON Geneva Observatory 1290 Sauverny, Switzerland 1. Introduction During

THE STELLAR VARIABILITY FROM HIPPARCOS PHOTOMETRY M. GRENON Geneva Observatory 1290 Sauverny, Switzerland 1. Introduction During the development of the Hipparcos satellite, the opportunity to use the star mapper to perform a whole sky two colour intermediate accuracy photometric survey, and the main-mission detector for high accuracy photometry of target stars was identified. The instrument was optimised and the pre-launch calibrations performed to pre-determine the pass-bands with an accuracy suf ficient to cope, in-orbit, with the foreseen aging of the detection chains. Photometry became an important by-product of the mission, very complementary to the astrometric results. It was the first opportunity to monitor the sky during 3-4 years without selection biases and with a precision similar to that achieved from the ground with the best classical techniques. A systematic detection of small amplitude variables was the expected return. 2. The correction of the aging effect The radiation by cosmic and solar particles induced transmission losses mainly in the green to violet part of the spectrum. Since the Hp band is broad, AA 380-900 nm, the effect was a chromatic change of the band, and hence of the Hp magnitude as large as 0.6 and 0.2 mag over the mission for V-I = 0 and 7 mag respectively. Photometric reductions were performed twice a day using a subset of the 29000 standard stars. Zero-point errors on the magnitude scale were then less than 0.001 mag for each data set. Correction of chromatic drifts requires the knowledge of the star colour; consequently error on it induces a linear trend in the Hp time series. -

List of Participants

LIST OF PARTICIPANTS H. ABLES, US Naval Observatory, Flagstaff, USA M. ANDRACACOU, Dept. of Astronomy, University of Athens, Greece E. ANTONOPOULOU, Dept. of Astronomy, University of Athens, Greece I. APPENZELLER, Landessternwarte Konigstuhl, Heidelberg, Germany T. ARMANDROFF, Yale University Observatory, New Haven, CT, USA M. AZZOPARDI, European Southern Observatory, München, Germany G. BERTELLI, Istituto di Astronomia, Padova, Italy G. BODIFEE, Astrofysisch Instituut, University of Brussels, Belgium. Β. BOHANNAN, university of Colorado, Boulder, USA J. BREYSACHER, European Southern Observatory, München, Germany A. CAMPBELL, Institute of Astronomy, Cambridge, England C. CHIOSI, Istituto di Astronomia, Padova, Italy M. CHRYSSOVERGIS, University of Athens, Greece Y. CHU, Astronomy Dept., University of Illinois, Urbana, USA P. CONTI, University of Colorado, Boulder, USA A. DAPERGOLAS, National Observatory Athens, Greece J.P. DE GREVE, Astrofysisch Instituut, University of Brussels, Belgium. M. DE GROOT, Armagh Observatory, Northern Ireland C. DE JAGER, Space Research Laboratory, Utrecht, the Netherlands C. DE LOORE, Astrofysisch Instituut, University of Brussels, Belgium. P. DUBOIS, Observatoire de Strasbourg, France M. FEAST, South African Astronomical Observatory, South Africa W. FREEDMAN, Mount Wilson and Los Campanos Observatory, Pasadena, California, USA E. GAVRYUSEVA, Inst, for Nuclear Research, Acad, of Sciences, Moscow, U.S.S.R. J. GRAHAM, Joint Institute for Laboratory Astrophysics University of Colorado and National Bureau of Standards, USA. L. GREGG10, Istituto di Astronomia, Padova, Italy. D. HATZIDIMITRIOÜ, National Observatory Athens, Greece P. HELLINGS, Astrofysisch Instituut, University of Brussels, Belgium. D. HILLIER, Mt. Stromlo Observatory, Woden P.O., Australia P. HODGE, Astronomy Dept. University of Washington, Seattle USA J. HOESSEL, Space Telescope Science Institute, Baltimore, USA I. HOWARTH, Dept. -

The Catalogue of Radial Velocity Standard Stars for Gaia I. Pre-Launch

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. RV˙final c ESO 2018 March 19, 2018 The catalogue of radial velocity standard stars for Gaia ⋆ ⋆⋆ I. Pre-launch release C. Soubiran1, G. Jasniewicz2, L. Chemin1, F. Crifo3, S. Udry4, D. Hestroffer5, and D. Katz3 1 LAB UMR 5804, Univ. Bordeaux - CNRS, F-33270, Floirac, France e-mail: [email protected] 2 LUPM UMR 5299 CNRS/UM2, Universit´eMontpellier II, CC 72, 34095 Montpellier Cedex 05, France 3 GEPI, Observatoire de Paris, CNRS, Universit´eParis Diderot, 5 place Jules Janssen, 92190 Meudon, France 4 Observatoire de Gen`eve, Universit´ede Gen`eve, 51 Ch. des Maillettes, 1290 Sauverny, Switzerland 5 IMCCE, Observatoire de Paris, UPMC, CNRS UMR8028, 77 Av. Denfert-Rochereau, 75014 Paris, France Received March 19, 2018; accepted XX ABSTRACT The Radial Velocity Spectrograph (RVS) on board of Gaia needs to be calibrated using stable reference stars known in advance. The catalogue presented here was built for that purpose. It includes 1420 radial velocity standard star candidates selected on strict criteria to fulfil the Gaia-RVS requirements. A large programme of ground-based observations has been underway since 2006 to monitor these 1 stars and verify their stability, which has to be better than 300 m s− over several years. The observations were done on the echelle spectrographs ELODIE and SOPHIE on the 1.93-m telescope at Observatoire de Haute-Provence (OHP), NARVAL on the T´elescope Bernard Lyot at Observatoire du Pic du Midi and CORALIE on the Euler-Swiss Telescope at La Silla. Data from the OHP and Geneva Observatory archives have also been retrieved as have HARPS spectra from the ESO archive. -

ELODIE Low-Mass Companions to Solar-Type Stars

Planetary Systems in the Universe - Observation, Formation and Evolution Proceedings lAU Symposium No. 202, @2004 lAU Alan Penny, Pawel Artymowicz, Anne-Marie Lagrange, & Sara Russell, eds. ELODIE low-mass companions to solar-type stars D. Naef, M. Mayor, D. Queloz, S. Udry Geneva Observatory, CH-1290 Sauverny, Switzerland F. Arenou DASGAL, Observatoire de Paris, F-92195 Meudon CEDEX, France J .-L. Beuzit, C. Perrier-Bellet Observatoire de Grenoble, UJF, BP 53, F-38041 Grenoble, France J.-P. Sivan Observatoire de Haute-Provence, F-04870 St-Michel, France Abstract. We present radial-velocity measurements for three solar-type stars (HD 127506, HD 174457 and HD 185414) hosting low-mass companions. The measurements were obtained with the ELODIE echelle spectrograph mounted on the 1.93-m telescope at Observatoire de Haute-Provence (CNRS, France) within the frame of the OHP-ELODIE Planet Search Programme. The in- ferred minimum masses of the detected companions are in the substellar mass range. Combining ELODIE radial-velocity data and HIPPARCOS astrometric data, the inclination angles of the orbital planes of HD 127506 and HD 174457 have been derived providing us with the de-projected masses of the companions: m2 = 44MJup for the companion of HD 127506 and m2 = 0.13M0 for the com- panion of HD 174457. Moreover, using adaptive optics measurements, we show that HD 174457 is probably a (F8V + M7V + M3-4V) triple system. To date, only a minimal orbital solution is available for HD 185414. 1. Introduction 6 years after the OHP-ELODIE Planet Search Programme (Mayor & Queloz 1996) was initiated, the number of planetary companions detected with the ELODIE spectrograph (Baranne et al, 1996) reaches 5 (see Sivan et al., this volume). -

TRAPPIST: Transiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope

Telescopes and Instrumentation TRAPPIST: TRAnsiting Planets and PlanetesImals Small Telescope Emmanuël Jehin1 Michaël Gillon1 Didier Queloz2 E. Jehin/ESO E. Pierre Magain1 Jean Manfroid1 Virginie Chantry1 Monica Lendl2 Damien Hutsemékers1 Stephane Udry2 1 Institut d’Astrophysique de l’Université de Liège, Belgium 2 Observatoire de l’Université de Genève, Switzerland TRAPPIST is a 60-cm robotic telescope that was installed in April 2010 at the ESO La Silla Observatory. The project is led by the Astrophysics and Image Pro- cessing group (AIP) at the Department of Figure 1. The TRAPPIST telescope in its 5metre time is obviously needed to monitor the Astrophysics, Geophysics and Ocean- enclosure at the La Silla Observatory, Chile. activity of several comets with a fre ography (AGO) of the University of Liège, quency of a few times per week. Some in close collaboration with the Geneva TRAPPIST is an original project using a comets are known, but others appear Observatory, and has been funded by single telescope that has been built and serendipitously. For the latter, telescope the Belgian Fund for Scientific Research optimised to allow the study of those two availability is crucial if we want to react (F.R.S.-FNRS) and the Swiss National aspects of the growing field of astrobiol rapidly to observe those targets at the Science Foundation (SNF). It is devoted ogy. It provides high quality photometric appropriate moment and for several hours to the detection and characterisation of data of exoplanet transits and allows or nights in a row; this strategy can pro exoplanets and to the study of comets the gaseous emissions of bright comets vide unique datasets impossible to obtain and other small bodies in the Solar Sys- to be monitored regularly.