Case Study: Boston

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 the Breakdown of Law Enforcement Focused Deterrence Programs: An

1 The Breakdown of Law Enforcement Focused Deterrence Programs: An Examination of Key Factors and Issues Approved: Dr. Cody Gaines Date 5/21/2019 2 The Breakdown of Law Enforcement Focused Deterrence Programs: An Examination of Key Factors and Issues A Seminar Research Paper Presented to the School of Graduate Studies at the University of Wisconsin – Platteville In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Masters of Science in Criminal Justice Gary J. Pihlaja Spring Semester 2019 3 Acknowledgements Most importantly, I want to thank my wife, Marie, and my two children, Kaylee and Frederick. Your patience and support during this endeavor has been unwavering despite all the times I could not play or had to miss a family event because of schoolwork. I could not have done this without you. Words cannot express my appreciation and love to you all. Thank you to my faculty paper advisor, Dr. Cody Gaines, for your support and feedback during this process. This research was a new challenge for me and your guidance definitely made it less intimidating. Finally, I want to thank Chief Michael Koval, Assistant Chief Paige Valenta, and Detective Brian Baney from the City of Madison Police Department. Chief Koval, you believed in me enough to approve tuition reimbursement for the majority of my Criminal Justice Master’s Degree program. I am extremely grateful to you for financing this opportunity. Assistant Chief Valenta and Detective Baney, our conversations about focused deterrence sparked my interest in this area of criminal justice. I regard you both as mentors and have been honored to work with you over the years. -

Final Report on the Indianapolis Violence Reduction Partnership

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Strategic Approaches to Reducing Firearms Violence: Final Report on the Indianapolis Violence Reduction Partnership Author(s): Edmund F. McGarrell ; Steven Chermak Document No.: 203976 Date Received: January 2004 Award Number: 99-IJ-CX-K002 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Strategic Approaches to Reducing Firearms Violence: Final Report on the Indianapolis Violence Reduction Partnership Edmund F. McGarrell School of Criminal Justice Michigan State University Steven Chermak Department of Criminal Justice Indiana University Final Report Submitted to the National Institute of Justice* Grant #1999-7114-IN-IJ and #1999-7119-IN-IJ January 2003 Revised October 2003 *Points of view or opinions expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice or the U.S. Department of Justice. Strategic Approaches to Reducing Firearms Violence: Final Report on the Indianapolis Violence Reduction Partnership Executive Summary The Indianapolis Violence Reduction Partnership (IVRP) was a multi-agency, collaborative effort to reduce homicide and serious violence in Marion County (Indianapolis), Indiana. The IVRP was part of the U.S. -

Reducing Gang Violence Using Focused Deterrence: Evaluating the Cincinnati Initiative to Reduce Violence (CIRV) Robin S

This article was downloaded by: [University of Cincinnati Libraries], [Robin Engel] On: 07 December 2011, At: 09:12 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Justice Quarterly Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjqy20 Reducing Gang Violence Using Focused Deterrence: Evaluating the Cincinnati Initiative to Reduce Violence (CIRV) Robin S. Engel, Marie Skubak Tillyer & Nicholas Corsaro Available online: 07 Nov 2011 To cite this article: Robin S. Engel, Marie Skubak Tillyer & Nicholas Corsaro (2011): Reducing Gang Violence Using Focused Deterrence: Evaluating the Cincinnati Initiative to Reduce Violence (CIRV), Justice Quarterly, DOI:10.1080/07418825.2011.619559 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2011.619559 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and- conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

Resource Guide: a Systematic Approach to Improving Community Safety

Senator Charles E. Shannon, Jr. Community Safety Initiative FY 2011 Grant Program Resource Guide: A Systematic Approach to Improving Community Safety Executive Office of Public Safety and Security Office of Grants and Research Research and Policy Analysis Division July, 2008 Table of Contents Introduction...................................................................................................................................................... 3 Section I: Defining the Problem................................................................................................................... 4 Using Data................................................................................................................................... 4 Focusing on Specifics ................................................................................................................. 4 Building Consensus .................................................................................................................... 4 Resources Available ................................................................................................................... 5 Section II: Comprehensive Gang Model ...................................................................................................... 6 Resources Available ................................................................................................................... 6 Table 1: Overview of OJJDP Comprehensive Gang Model........................................................ 7 Section -

Problem-Oriented Policing, Deterrence, and Youth Violence: an Evaluation of Boston’S Operation Ceasefire

JOURNALBraga et al. OF/ PROBLEM-ORIENTED RESEARCH IN CRIME POLICING AND DELINQUENCY PROBLEM-ORIENTED POLICING, DETERRENCE, AND YOUTH VIOLENCE: AN EVALUATION OF BOSTON’S OPERATION CEASEFIRE ANTHONY A. BRAGA DAVID M. KENNEDY ELIN J. WARING ANNE MORRISON PIEHL Operation Ceasefire is a problem-oriented policing intervention aimed at reducing youth homicide and youth firearms violence in Boston. It represented an innovative partnership between researchers and practitioners to assess the city’s youth homicide problem and implement an intervention designed to have a substantial near-term impact on the problem. Operation Ceasefire was based on the “pulling levers” deter- rence strategy that focused criminal justice attention on a small number of chronically offending gang-involved youth responsible for much of Boston’s youth homicide problem. Our impact evaluation suggests that the Ceasefire intervention was associ- ated with significant reductions in youth homicide victimization, shots-fired calls for service, and gun assault incidents in Boston. A comparative analysis of youth homi- cide trends in Boston relative to youth homicide trends in other major U.S. and New England cities also supports a unique program effect associated with the Ceasefire intervention. Although overall homicide rates in the United States declined between the 1980s and 1990s, youth homicide rates, particularly incidents involving fire- arms, increased dramatically. Between 1984 and 1994, juvenile (younger than 18) homicide victimizations committed with handguns increased by 418 percent, and juvenile homicide victimizations committed with other guns in- This research was supported under award 94-IJ-CX-0056 from the National Institute of Jus- tice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. -

Losing Faith? Police, Black Churches, and the Resurgence of Youth Violence in Boston

PUBLIC SAFETY Losing Faith? Police, Black Churches, and the Resurgence of Youth Violence in Boston By Anthony A. Braga and David Hureau (Harvard Kennedy School) and Christopher Winship (Faculty of Arts and Sciences and Harvard Kennedy School) May 2008 Revised October 2008 RAPPAPORT INSTITUTE for Greater Boston Losing Faith? Police, Black Churches, and the Resurgence of Youth Violence in Boston Authors Anthony A. Braga is a Senior Research Associate and Lecturer in Public Policy at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government and a Senior Research Fellow at the Berkeley Center for Criminal Justice, University of California, Berkeley. David Hureau is a Research Associate in the Program in Criminal Justice Policy and Management at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. Christopher Winship is the Diker-Tishman Professor of Sociology in Harvard’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences and is a faculty member at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank Commissioner Edward Davis, Superintendent Paul Joyce, Superintendent Kenneth Fong, Deputy Superintendent Earl Perkins, and Carl Walter of the Boston Police Department for their assistance in the acquisition of the data presented in this article. We also would like to thank Brian Welch and Baillie Aaron for their excellent assistance in the completion of this article. A version of this paper is forthcoming in the Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law. © 2008 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. The research presented here was primarily supported by funds from the Russell Sage Foundation and the Boston Foundation with support from the Rappaport Institute for Greater Boston. -

Evolving Strategy of Policing: Case Studies of Strategic Change

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Evolving Strategy of Policing: Case Studies of Strategic Change Author(s): George L. Kelling ; Mary A. Wycoff Document No.: 198029 Date Received: December 2002 Award Number: 95-IJ-CX-0059 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Page 1 Prologue. Draft, not for circulation. 5/22/2001 e The Evolving Strategy of Policing: Case Studies of Strategic Change May 2001 George L. Kelling Mary Ann Wycoff Supported under Award # 95 zscy 0 5 9 fiom the National Institute of Justice, Ofice of Justice Programs, U. S. Department of Justice. Points ofview in this document are those ofthe authors and do not necessarily represent the official position ofthe U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Prologue. Draft, not for circulation. 5/22/2001 Page 2 PROLOGUE Orlando W. Wilson was the most important police leader of the 20thcentury. -

Promising Strategies for Violence Reduction: Lessons from Two Decades of Innovation

Promising Strategies for Violence Reduction: Lessons from Two Decades of Innovation Edmund F. McGarrell Natalie Kroovand Hipple Timothy S. Bynum Heather Perez Karie Gregory School of Criminal Justice Michigan State University 560 Baker Hall East Lansing, MI 48824 and Candice M. Kane Charles Ransford School of Public Health University of Illinois at Chicago 1603 West Taylor Street Chicago, Illinois 60612 March 29, 2013 Project Safe Neighborhoods Case Study Report #13 This project was supported by Grant #2009-GP-BX-K054 awarded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance. The Bureau of Justice Assistance is a component of the Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the National Institute of Justice, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, the Office for Victims of Crime, and the Office of Sex Offender Sentencing, Monitoring, Apprehending, Registering, and Tracking. Points of view or opinions in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Promising Violence Reduction Initiatives Project Safe Neighborhoods Case Study Report Since reaching peak levels in the early 1990s, the United States has witnessed a significant decline in levels of homicide and gun-related crime. Indeed, whereas in 1991 there were more than 24,000 homicides in the United States (9.8 per 100,000 population), this number declined to less than 15,000 in 2010 (4.8 per 100,000 population) (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2011). Similarly, the number of violent victimizations declined from more than 16 million in 1993 to less than six million in 2011 (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2013). -

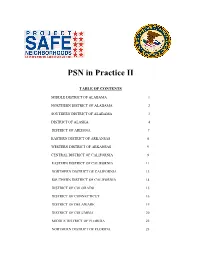

PSN in Practice II

PSN in Practice II TABLE OF CONTENTS MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA 1 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA 2 SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA 3 DISTRICT OF ALASKA 4 DISTRICT OF ARIZONA 7 EASTERN DISTRICT OF ARKANSAS 8 WESTERN DISTRICT OF ARKANSAS 9 CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 9 EASTERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 11 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 13 SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 14 DISTRICT OF COLORADO 15 DISTRICT OF CONNECTICUT 16 DISTRICT OF DELAWARE 19 DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA 20 MIDDLE DISTRICT OF FLORIDA 22 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA 23 SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA 25 MIDDLE DISTRICT OF GEORGIA 27 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA 28 SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA 30 DISTRICTS OF GUAM AND THE NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS 31 DISTRICT OF HAWAII 32 DISTRICT OF IDAHO 33 CENTRAL DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS 35 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS 36 SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS 37 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF INDIANA 38 SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF INDIANA 39 NORTHERN AND SOUTHERN DISTRICTS OF IOWA 40 DISTRICT OF KANSAS 41 EASTERN DISTRICT OF KENTUCKY 42 WESTERN DISTRICT OF KENTUCKY 43 EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA 44 MIDDLE DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA 46 WESTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA 47 DISTRICT OF MAINE 49 DISTRICT OF MARYLAND 50 DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS 52 EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN 54 WESTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN 56 DISTRICT OF MINNESOTA 57 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI 58 SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI 60 EASTERN DISTRICT OF MISSOURI 61 WESTERN DISTRICT OF MISSOURI 62 DISTRICT OF MONTANA 63 DISTRICT OF NEBRASKA 64 DISTRICT OF NEVADA 65 DISTRICT OF NEW HAMPSHIRE 66 DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY -

Reducing Gun Violence: the Boston Gun Project's Operation Ceasefire

Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • BostonU.S. • Boston Department • Boston of • JusticeBoston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • BostonOffice • Boston of Justice• Boston Programs • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • BostonNational • Boston Institute • Boston of • Justice Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston •RESEARCH Boston • Boston •REPORT Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston • Boston -

Rethinking Law Enforcement Strategies to Prevent Domestic

RethinkingRethinking LawLaw EnforcementEnforcement StrategiesStrategies ttoo PPreventrevent DomesDomestictic ViolenceViolence BY DAVID M. KENNEDY 8 NATIONAL CENTER FOR VICTIMS OF CRIMEI NETWORKSI SPRING/SUMMER 2004 trategies for addressing Domestic Violence S domestic violence have Offenders as “Special” traditionally been strong- Domestic violence advocates, researchers, ly victim-focused, with a and theorists have tended to argue that heavy emphasis on helping domestic violence is “special”—fundamen- victims avoid patterns of intimacy with tally unlike other kinds of violence—and abusers, disengage from abusers with that domestic violence offenders are simi- whom they are involved, physically larly special. Students of domestic vio- remove themselves from abusive settings, lence have argued that “[domestic vio- and address the damage created by abuse lence] is a special and unique kind of vio- and patterns of abuse. lence and should not be approached as a This narrow focus on domestic violence subset of general violent behavior.”4 victims has had the effect of limiting how Because those who assault other family experts think about approaching the prob- members are often depicted as otherwise lem. As a result, potentially more effective law-abiding citizens, there is no com- strategies, such as using law enforcement pelling reason to apply broader notions of to control offenders, have failed to criminality.5 This conception of the “batter- emerge. Where criminal justice strategies er as anyone”6 led to a clear distinction have played -

The District of Columbia Mayor's Focused Improvement Area Initiative: Review of the Literature Relevant to Collaborative

The District of Columbia Mayor’s Focused Improvement Area Initiative: Review of the Literature Relevant to Collaborative Crime Reduction Jesse Jannetta Megan Denver Caterina Gouvis Roman Nicole Prchal Svajlenka Martha Ross Benjamin Orr Dec 2010 The District of Columbia Crime Policy Institute (DCPI) was established at the Urban Institute in collabora- tion with the Brookings Institution, through the jointly administered Partnership for Greater Washington Research with funding from the Justice Grants Administration in the Executive Office of the Mayor. DCPI is a nonpartisan, public policy research organization focused on crime and justice policy in Washington, DC. DCPI’s mission is to support improvements in the administration of justice policy through evidence-based research. An assessment of the Mayor’s Focused Improvement Areas (FIA) Initiative is one of DCPI’s three original research projects in FY2010. For more information on DCPI, see http://www.dccrimepolicy.org ©2011. The Urban Institute. All rights reserved. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the District of Columbia Crime Policy Institute, the Urban Institute, the Brookings Institution, their trustees, or their funders. This report was funded by the Justice Grants Administration, Executive Office of the District of Columbia Mayor under sub-grant 2009-JAGR-1114. Tables i Figures ii Acronyms iii 1 Introduction 1 2 Programmatic Elements 5 2.1 Crime and Violence Intervention . .5 2.1.1 Problem Analysis . .5 2.1.2 Targeting the Intervention . .8 2.1.3 Community Policing . .9 2.1.4 Suppression . 10 2.1.5 Focused Deterrence . 11 2.1.6 Reentry Programs .