Characteristics and Professional Qualifications of NCAA Divisions II and III Athletic Directors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 NCAA Division I Baseball Championship Bracket

Regionals Super Regionals Division III World Series Super Regionals Regionals May 17-19 May 24-25 May 31- June 4/5 May 24-25 May 17-19 Double Elimination Best-of-Three Games Cedar Rapids, Iowa Best-of-Three Games Double Elimination OR Best-of-five Double Elimination OR Best-of-five First-Round Pairings Best-of-Three Finals First-Round Pairings *Southern Me. (34-7) Webster (31-10) vs. vs. New England Col. (25-15) Bethany Lutheran (23-16) New England College Webster Oswego St. (29-12) Regional Champion Regional Champion *Wis.-Whitewater (34-9) vs. vs. MIT (22-17-1) North Central (IL) (31-11) Super Regional Champion Super Regional Champion *UMass Boston (29-11) *Concordia Chicago (38-6) vs. vs. Baruch (17-18) Buena Vista (24-17) *UMass Boston *Concordia Chicago Wheaton (MA) (27-10) Regional Champion Regional Champion Baldwin Wallace (25-15) vs. vs. St. Joseph's (ME) (32-10) Saint John's (MN) (32-12) Babson (33-7) *Wooster (26-12) vs. vs. Keystone (25-13) Rochester (NY) (28-15) *Babson Wooster *Trinity (CT) (26-7) Regional Champion Regional Champion CWRU (22-13) vs. vs. Salve Regina (27-16) Otterbein (26-16-1) Super Regional Champion Super Regional Champion Denison (38-7) *SUNY Cortland (31-11-1) vs. vs. La Roche (30-13) Alvernia (28-14-2) *Heidelberg SUNY Cortland Regional Champion Heidelberg (30-13) Penn St. Harrisburg (32-13-1) Regional Champion vs. vs. *Adrian (35-7) Tufts (27-8) Ithaca (31-7) vs. *Chapman (33-9) Westfield St. (27-14) *Chapman Shenandoah Whitman (26-18) Regional Champion Regional Champion *Kean (29-14) vs. -

2020-21 MANUAL NCAA General Administrative Guidelines

2020-21 MANUAL NCAA General Administrative Guidelines Contents Section 1 • Introduction 2 Section 1•1 Definitions 2 Section 2 • Championship Core Statement 2 Section 3 • Concussion Management 3 Section 4 • Conduct 3 Section 4•1 Certification of Eligibility/Availability 3 Section 4•2 Drug Testing 4 Section 4•3 Honesty and Sportsmanship 4 Section 4•4 Misconduct/Failure to Adhere to Policies 4 Section 4•5 Sports Wagering Policy 4 Section 4•6 Student-Athlete Experience Survey 5 ™ Section 5 • Elite 90 Award 5 Section 6 • Fan Travel 5 Section 7 • Logo Policy 5 Section 8 • Research 6 Section 9 • Division I 6 Section 9•1 Religious Conflicts 6 THE NATIONAL COLLEGIATE ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION P.O. Box 6222 Indianapolis, Indiana 46206-6222 317-917-6222 ncaa.org November 2020 NCAA, NCAA logo, National Collegiate Athletic Association and Elite 90 are registered marks of the Association and use in any manner is prohibited unless prior approval is obtained from the Association. NCAA PRE-CHAMPIONSHIPS MANUAL 1 GENERAL ADMINISTRATIVE GUIDELINES Section 1 • Introduction The Pre-Championship Manual will serve as a resource for institutions to prepare for the championship. This manual is divided into three sections: General Administrative Guidelines, Sport-Specific Information, and Appendixes. Sections one through eight apply to policies applicable to all 90 championships, while the remaining sections are sport specific. Section 1•1 Definitions Pre-championship Manual. Resource for institutions to prepare for the championship. Administrative Meeting. Pre-championship meeting for coaches and/or administrators. Appendixes. Any supplemental documents to be provided and distributed through the various resources. Championship Manager. -

Things to Know About Volleyball Recruiting

THINGS TO KNOW ABOUT VOLLEYBALL RECRUITING Terms to Know NCAA Clearinghouse or Eligibility Center (eligibilitycenter.org) – is the NCAA office that certifies a student-athletes academic credentials to be eligible for Division I and II athletics. You cannot make an official visit to a DI or DII school without being at least registered with the clearinghouse. NCAA Division I – 325 Volleyball teams at some of the most well known schools (Florida, Texas, Duke, Rutgers, Seton Hall, Rider etc). Division I schools are permitted to offer scholarships to up to 12 student athletes for volleyball. Schools that are “fully funded” will only offer full scholarships. Partially funded programs will split scholarships and stack with academic and need based aid money to make you an offer. The season is August and into December, with off-season training through the spring and even summer months at many schools. This is the highest level of college athletics, and is the most demanding. NCAA Division II – 250ish Volleyball teams at lesser known schools (Felician, Georgian Court, Tampa, Lemoyne, Millersville, CW Post). Division II schools are permitted to divide the value of 8 full scholarships among a larger number of student athletes. Many DII schools only have between 1-3 scholarships, which they divide and stack with academic and need based aid, but seldom is it a full package. The season lasts from August through November, with either a limited spring training season, or they have recently approved the addition of beach volleyball as a spring sport which some schools may be adding soon. NCAA Division III – 425 Volleyball teams at a variety of schools (including NYU, Chicago, Johns Hopkins, Williams, Scranton, Kean, St. -

Summary of NCAA Regulations NCAA Division III

Academic Year 2011-12 Summary of NCAA Regulations NCAA Division III For: Student-athletes. Purpose: To summarize NCAA regulations regarding eligibility of student- athletes to compete. DISCLAIMER: THE SUMMARY OF NCAA REGULATIONS DOES NOT INCLUDE ALL NCAA DIVISION III BYLAWS. FOR A COMPLETE LIST, GO TO WWW.NCAA.ORG. YOU ARE RESPONSIBLE FOR KNOWING AND UNDERSTANDING THE APPPLICATION OF ALL BYLAWS RELATED TO YOUR ELIGIBILITY TO COMPETE. CONTACT YOUR INSTITUTION'S COMPLIANCE OFFICE OR THE NCAA IF YOU HAVE QUESTIONS. TO: STUDENT-ATHLETE This summary of NCAA regulations contains information about your eligibility to compete in intercollegiate athletics. This summary has two parts: 1. Part I is for all student-athletes. 2. Part II is for new student-athletes only (those signing the Student-Athlete Statement for the first time). If you have questions, ask your director of athletics (or his or her official designee) or refer to the 2011-12 NCAA Division III Manual. The references in brackets after each summarized regulation show you where to find the regulation in the Division III Manual. Part I: FOR ALL STUDENT-ATHLETES. This part of the summary discusses ethical conduct, amateurism, financial aid, academic standards and other regulations concerning your eligibility for intercollegiate competition. 1. Ethical Conduct – All Sports. a. You must act with honesty and sportsmanship at all times so that you represent the honor and dignity of fair play and the generally recognized high standards associated with wholesome competitive sports. [NCAA Bylaw 10.01.1] Summary of NCAA Regulations – NCAA Division III Page No. 12 _________ b. You have engaged in unethical conduct if you refuse to furnish information relevant to an investigation of a possible violation of an NCAA regulation when requested to do so by the NCAA or your institution. -

2020-21 MANUAL NCAA General Administrative Guidelines

2020-21 MANUAL NCAA General Administrative Guidelines Contents Section 1 • Introduction 2 Section 1•1 Definitions 2 Section 2 • Championship Core Statement 2 Section 3 • Concussion Management 3 Section 4 • Conduct 3 Section 4•1 Certification of Eligibility/Availability 3 Section 4•2 Drug Testing 4 Section 4•3 Honesty and Sportsmanship 4 Section 4•4 Misconduct/Failure to Adhere to Policies 4 Section 4•5 Sports Wagering Policy 4 Section 4•6 Student-Athlete Experience Survey 5 ™ Section 5 • Elite 90 Award 5 Section 6 • Fan Travel 5 Section 7 • Logo Policy 5 Section 8 • Research 6 Section 9 • Division III 6 Section 9•1 Division III Philosophy 6 Section 9•2 Commencement Conflicts 6 Section 9•3 Gameday the DIII Way 7 Section 9•4 Religious Conflicts 7 THE NATIONAL COLLEGIATE ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION P.O. Box 6222 Indianapolis, Indiana 46206-6222 317-917-6222 ncaa.org November 2020 NCAA, NCAA logo, National Collegiate Athletic Association and Elite 90 are registered marks of the Association and use in any manner is prohibited unless prior approval is obtained from the Association. NCAA PRE-CHAMPIONSHIP MANUALS 1 GENERAL ADMINISTRATIVE GUIDELINES Section 1 • Introduction The Pre-Championship Manual will serve as a resource for institutions to prepare for the championship. This manual is divided into three sections: General Administrative Guidelines, Sport-Specific Information, and Appendixes. Sections one through eight apply to policies applicable to all 90 championships, while the remaining sections are sport specific. Section 1•1 Definitions Pre-championship Manual. Resource for institutions to prepare for the championship. Administrative Meeting. Pre-championship meeting for coaches and/or administrators. -

NCAA Division II Championship Cardinal Club Golf Course Simpsonville, KY NCAA Tees Dates: May 15 - May 19

NCAA Division II Championship Cardinal Club Golf Course Simpsonville, KY NCAA Tees Dates: May 15 - May 19 Start Finish Player Team Scores 1 1 Josh Creel Central Oklahoma 65 70 135 -9 T36 2 Eric Frazzetta Chico State 73 63 136 -8 T3 T3 Daniel Stapff Barry 69 68 137 -7 T5 T3 Jim Knous Colorado Sc.of Mines 70 67 137 -7 2 5 Zack Kempa Indiana U. of Pa. 68 70 138 -6 T5 6 Ben Taylor Nova Southeastern 70 69 139 -5 T3 7 Hayden Letien S. Carolina-Aiken 69 71 140 -4 T5 T8 Jordan Walor UNC Pembroke 70 71 141 -3 T23 T8 J.P. Griffin * Georgia Southwestern 72 69 141 -3 T47 T8 Kyle Chappell * Dixie State College 74 67 141 -3 T5 T8 Rob Damschen CSU-Stanislaus 70 71 141 -3 T14 T8 Paul Tighe Wilmington (DE) 71 70 141 -3 T47 T13 J.P. Solis S. Carolina-Aiken 74 68 142 -2 T23 T13 Luke Kwon St. Edward's 72 70 142 -2 T14 T13 Bobby Bucey Chico State 71 71 142 -2 T14 T13 Kyle Souza Chico State 71 71 142 -2 T47 T13 Trevor Blair CSU-Stanislaus 74 68 142 -2 T23 T18 Dylan Goodwin Western Washington 72 71 143 -1 T5 T18 Patrick Garrett Georgia Coll. & State 70 73 143 -1 T5 T18 Ryan Trocchio Georgia Coll. & State 70 73 143 -1 T14 T21 Sandy Vaughan Western Washington 71 73 144 E T23 T21 Taylor Smith Georgia Coll. & State 72 72 144 E T23 T21 Cy Moritz Central Missouri 72 72 144 E T36 T21 Brad Boyle Indiana U. -

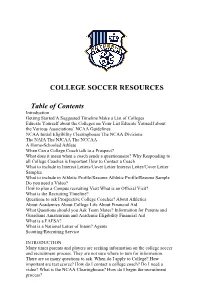

COLLEGE SOCCER RESOURCES Table of Contents

COLLEGE SOCCER RESOURCES Table of Contents Introduction Getting Started/A Suggested Timeline Make a List of Colleges Educate Yourself about the Colleges on Your List Educate Yourself about the Various Associations’ NCAA Guidelines NCAA Initial Eligibility Clearinghouse The NCAA Divisions The NAIA The NJCAA The NCCAA A Home-Schooled Athlete When Can a College Coach talk to a Prospect? What does it mean when a coach sends a questionnaire? Why Responding to all College Coaches is Important How to Contact a Coach What to include in Interest Letters/Cover Letter Interest Letter/Cover Letter Samples What to include in Athletic Profile/Resume Athletic Profile/Resume Sample Do you need a Video? How to plan a Campus recruiting Visit What is an Official Visit? What is the Recruiting Timeline? Questions to ask Prospective College Coaches? About Athletics About Academics About College Life About Financial Aid What Questions should you Ask Team Mates? Information for Parents and Guardians Amateurism and Academic Eligibility Financial Aid What is a FAFSA? What is a National Letter of Intent? Agents Scouting/Recruiting Service INTRODUCTION Many times parents and players are seeking information on the college soccer and recruitment process. They are not sure where to tum for information. There are so many questions to ask. When do I apply to College? How important are test scores? How do I contact a college coach? Do I need a video? What is the NCAA Clearinghouse? How do I begin the recruitment process? It is very important to know that no one course is correct for everyone. Each school and coach may handle the process differently for their prospective student-athletes. -

2020-21 Pre-Championships Manual

2020-21 MANUAL NCAA General Administrative Guidelines Contents Section 1 • Introduction 2 Section 1•1 Definitions 2 Section 2 • Championship Core Statement 2 Section 3 • Concussion Management 3 Section 4 • Conduct 3 Section 4•1 Certification of Eligibility/Availability 3 Section 4•2 Drug Testing 4 Section 4•3 Honesty and Sportsmanship 4 Section 4•4 Misconduct/Failure to Adhere to Policies 4 Section 4•5 Sports Wagering Policy 4 Section 4•6 Student-Athlete Experience Survey 5 ™ Section 5 • Elite 90 Award 5 Section 6 • Fan Travel 5 Section 7 • Logo Policy 5 Section 8 • Research 6 Section 9 • Division I 6 Section 9•1 Religious Conflicts 6 THE NATIONAL COLLEGIATE ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION P.O. Box 6222 Indianapolis, Indiana 46206-6222 317-917-6222 ncaa.org November 2020 NCAA, NCAA logo, National Collegiate Athletic Association and Elite 90 are registered marks of the Association and use in any manner is prohibited unless prior approval is obtained from the Association. NCAA PRE-CHAMPIONSHIPS MANUAL 1 GENERAL ADMINISTRATIVE GUIDELINES Section 1 • Introduction The Pre-Championship Manual will serve as a resource for institutions to prepare for the championship. This manual is divided into three sections: General Administrative Guidelines, Sport-Specific Information, and Appendixes. Sections one through eight apply to policies applicable to all 90 championships, while the remaining sections are sport specific. Section 1•1 Definitions Pre-championship Manual. Resource for institutions to prepare for the championship. Administrative Meeting. Pre-championship meeting for coaches and/or administrators. Appendixes. Any supplemental documents to be provided and distributed through the various resources. Championship Manager. -

BB Guide 0607.Qxd

DustyRHODES Head Coach (20th Season) X 13 Conference Championships • 5 World Series Appearances • 16 Postseason Appearances ow entering his 20th season at the helm of the Ospreys, Nhead coach Dusty Rhodes has guided the program from NAIA, to NCAA Division II, and most recently to NCAA Division I - all the while building UNF into a nationally recognized baseball powerhouse. Rhodes has compiled an 802- 332 record through 19 seasons, guiding UNF to 16 postseason appearances, including five World Series appearances, four district championships while in NAIA and six conference championships in NCAA Division II. In 2004, he topped the 1,000- win career mark, and now holds an all-time record of 1,106-449. He was named Peach Belt Conference Coach of the Year in 1999, 2000, 2001, 2004 and 2005 and South Atlantic Region Coach of the Year in 2000, 2001 and 2005. A year ago, Rhodes led the UNF program into an arena that many believed the Ospreys should have been competing in for years - NCAA Division I. As usual, the UNF pro- in-state rival Florida Southern in the cham- 41-18 overall record. gram thrived while fighting through the rig- pionship game of the Division II National Since 1997, the Ospreys have failed to ors of college baseball's highest division - Baseball Championship. The Ospreys fin- win 40 games only twice - last year and in finishing with a 34-21 record and a 20-10 ished the season with a mark of 48-17 -- 2003 - and the 2003 squad was only one mark in the Atlantic Sun Conference. -

United Soccer Coaches Reveals NCAA Division III All-America Teams KANSAS CITY, Mo

United Soccer Coaches reveals NCAA Division III All-America Teams KANSAS CITY, Mo. (November 30, 2017) – United Soccer Coaches announced on Thursday the association’s NCAA Division III Men’s and Women’s All-America Teams on the eve of the 2017 NCAA Division III Men’s and Women’s Soccer Championship semifinals in Greensboro, North Carolina. A total of 92 players (46 men, 46 women) in NCAA Division III soccer receive All-America recognition this year, led by a trio of three-time All-Americans: Brandeis University midfielder Josh Ocel, Lynchburg College defender Emily Maxwell and University of Chicago senior midfielder Mia Calamari. This year’s NCAA Division III All-Americans, along with their families and coaches, will be formally acknowledged for their accomplishments at the United Soccer Coaches All-America Luncheon on January 20, 2018 at the Pennsylvania Convention Center in conjunction with the 2018 United Soccer Coaches Convention in downtown Philadelphia. In addition, the 2017 NCAA Division III Men's and Women’s All-Region Teams have been posted in the “Awards Central” section of UnitedSoccerCoaches.org. 2017 NCAA Division III Men’s All-America Teams First Team Pos Name Yr. School Hometown K Nate VanRyn Sr. Calvin College Grandville, Mich. D Conor Coleman Sr. Tufts University Phoenix, Ariz. D Tyler Joy-Brandon Jr. Transylvania University Lexington, Ky. D Caleb Vandergriff Jr. University Of Mary Hardin-Baylor Georgetown, Texas D Trent Vegter* Jr. Calvin College Hudsonville, Mich. M Shae Bottum* Sr. University of St. Thomas (Minn.) West Lakeland, Minn. M James Grace* Sr. Christopher Newport University Ashburn, Va. -

BRACKET 2015 DIII Baseball

2015 NCAA Division III Baseball - Central Regional Wartburg College - Waverly, Iowa May 13-16, 2015 Wis.-Stevens Point Game 1 Game 5 Greenville L3 Webster Game 2 Game 7 Carthage Game 10 Game 6 Wartburg Game 11 Game 3 W9 *If necessary Anderston (IN) *If necessary L10 L1 Game 4 L2 Game 8 L6 Game 9 L7 Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday G1 - Noon G4 – Noon G7 – Noon *G10 – Noon G2 – 3:30 pmG5 – 3:30 pm G8 – 3:30 p*G11 – 3:30 pm G3 – 7:00 pmG6 – 7:00 pm G9 – 7:00 pIf necessary 2015 NCAA Division III Baseball - Mid-Atlantic Regional York Revolution/Middle Atlantic Conferences - York, Pennsylvania May 13-17, 2015 Salisbury L1 Game 1 W1 W5 Mitchell W7 Game 5 Game 7 W10 Kean Game 10 L2 W2 Game 2 L8 Penn St.-Berks Game 11 W11 W12 Johns Hopkins Game 12 L3 Game 3 W3 W6 Misericorida Game 14 W14 W13 Game 13 Game 6 Game 8 W9 Alvernia W8 Game 9 Game 15 L4 Game 4 W4 L11 W13 L7 Catholic *If necessary 14 All times are local time. ©2015 National Collegiate Athletic Association. No commercial use without the NCAA's written permission. The NCAA opposes all forms of sports wagering. 2015 NCAA Division III Baseball - Mideast Regional Washington and Jefferson College - Washington, Pennsylvania May 13-16, 2015 Frostburg St. Game 1 Game 5 Wash. & Jeff. L3 Adrian Game 2 Game 7 Shenandoah Game 10 Game 6 Heidelberg Game 11 Game 3 W9 *If necessary La Roche *If necessary L10 L1 Game 4 L2 Game 8 L6 Game 9 L7 Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday G1 - time G4 - G7 - *G10 - G2 - G5 - G8 - *G11 - G3 - G6 - G9 - If necessary All times are local time. -

Print 07 Men Hockey Media Guide.Qxd

2006 – 2007 DATE DAY OPPONENT LOCATION TIME 10/20 Fri. Oswego State Away 7:00 PM 11/03 Fri. Hobart* Home 7:00 PM 11/04 Sat. Elmira* Away 7:00 PM 11/17 Fri. Neumann* Home 7:00 PM 11/18 Sat. Lebanon Valley* Home 7:00 PM 12/01 Fri. Manhattanville* Home 8:00 PM 12/02 Sat. Manhattanville* Home 8:00 PM 12/05 Tue. Hamilton Away 7:00 PM 12/08 Fri. Hamilton Home 7:00 PM 12/29 Fri. Norwich** Away 7:00 PM 12/30 Sat. Rhode Island/ Away 1:00 PM/ Amherst** 4:00 PM 1/05 Fri. Neumann* Away 7:00 PM 1/06 Sat. Neumann* Away 7:00 PM 1/09 Tue. Fredonia StateHome 7:00 PM 1/12 Fri. Cortland State Away 7:00 PM 1/19 Fri. Elmira* Home 7:00 PM 1/20 Sat. Elmira* Home 7:00 PM 1/23 Tue. Oswego State Home 7:00 PM 1/30 Tue. Williams Away 7:00 PM 2/02 Fri. Manhattanville* Away 7:30 PM 2/04 Sun. Nichols Home 3:00 PM 2/09 Fri. Lebanon Valley* Away 7:00 PM 2/10 Sat. Lebanon Valley* Away 3:00 PM 2/16 Fri. Hobart* Home 7:00 PM 2/17 Sat. Hobart* Away 4:00 PM 2/24 Sat. ECAC West Playoffs TBA TBA 3/03 Sat. ECAC West Playoffs TBA TBA 2006 2007 * ECAC West Conference Game ** Times Argus Invitational Hockey Tournament QQuick Facts Head Coach Gary Heenan was hired as head coach of the Utica College men's ice hockey program in August 2000.