Supreme Court, Appellate Division First Department

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News Release ______

News Release _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Contact: Darren Rogers Senior Director, Communications & Media Services Churchill Downs Racetrack (502) 636-4461 (office) (502) 345-1030 (mobile) [email protected] SIR TRUEBADOUR GIVES ASMUSSEN HIS RECORD-EQUALING FIFTH BASHFORD MANOR LOUISVILLE, Ky. (Saturday, June 30, 2018) – Whispering Oaks Farm LLC ’s Sir Truebadour led every step of the way in Saturday’s 117th running of the $100,000 Bashford Manor (Grade III) on closing day at Churchill Downs’ 38-day Spring Meet to beat Mr Chocolate Chip by two lengths and give Hall of Fame trainer Steve Asmussen an impressive fifth win in the nation’s first graded stakes race for 2-year-olds. Ridden by Ricardo Santana Jr., Sir Truebadour, who was sent to post as the hot 3-2 favorite, ran six furlongs over a fast main track in 1:12.77 – the slowest of 19 Bashford Manor renewals at the six-furlong distance. Sir Truebadour was leg weary late in the stretch but had a jump on his 11 rivals after breaking alertly from post 4. He battled from the inside with 48-1 longshot The Song of John and Mr. Granite for the early lead and ran the first quarter mile in a swift :21.35. The Song of John got within a half-length of Sir Truebadour at the top of the stretch but the winner spurted clear after a half mile in :45.63 and drew clear midway down the lane, and had enough to hold on comfortably. “Steve and his team did a great job with this horse,” Santana said. -

Lex Mastermap Handout

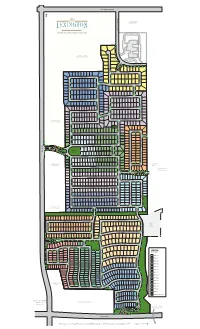

ELDORADO PARKWAY M A MM *ZONED FUTURE O TH LIGHT RETAIL C A VE LANE MASTER PLANNED GATED COMMUNITY *ZONED FUTURE RETAIL/MULTI-FAMILY M A J E MAMMOTH CAVE LANE S T T IN I C O P P L I R A I N R E C N E O C D I R C L ORB DRIVE E A R I S T MACBETH AVENUE I D E S D R I V E M SPOKANE WAY D ANUEL STRE ARK S G I A C T O AR LANE CARRY BACK LANE 7 M O E L T A N E 8 NORTHERN DANCER WAY GALLAHADION WAY GRINDS FUN N T Y CIDE ONE THUNDER GULCH WAY M C ANOR OU BROKERS TIP LANE R T M ANUEL STRE E PLAC RAL DMI WAR A E T DAY STAR WAY *ZONED FUTURE 3 LIGHT COMMERCIAL BOLD FORBES STREET FERDINAND VIEW LEON PONDER LANE A TUS LANE SEATTLE SLEW STREET GRAHAM AVENUE WINTE R GREEN DRIVE C OIT SECRETARIAT BOULEVARD C OUNT R O TURF DRIVE AD S AMENITY M A CENTER R T Y JONES STRE STRIKE GOLD BOULEVARD E T L 5 2 UC K Y DEBONAIR LANE C 1 A Yucca Ridge *ZONED FUTURE V FLYING EBONY STREET A LIGHT RETAIL L C Park ADE DRIVE AFFIRMED AVENUE Independence High School SUTHERLAND LANE AZRA TRAIL OMAHA DRIVE BOLD VENTURE AVENUE C L ONQUIS UC O XBOW K Y DEBONAIR LANE C 4 T A ADOR V A A VENUE L C ADE DRIVE WHIRLAWAY DRIVE C OU R 9T IRON LIEGE DRIVE *ZONED FUTURE IRON LIEGE DRIVE LIGHT COMMERCIAL 6 A M EMPIRE MAKER ROAD E RISEN STAR ROAD R I BUBBLING OVER C W A AR EMBLEM PL N Future P H City A R O Park A H D R A O R CE I AD V E DUST COMMANDER COURT FO DETERMINE DRIVE R W ARD P 14 ASS CI SPECTACULAR BID STREET REAL QUI R CLE E T R TIM TAM CIRCLE D . -

Wild Night Tapit Filly Tops Sale at $1.15 Million Fasig-Tipton/Photos by Z Fasig-Tipton/Photos SELENITE, MARK MY WAY WIN N.Y

Tuesday, August 5, 2014 Year 14 • No. 15 T he aratoga Saratoga’s Daily Newspaper on Thoroughbred Racing Wild Night Tapit filly tops sale at $1.15 million Fasig-Tipton/Photos by Z Fasig-Tipton/Photos SELENITE, MARK MY WAY WIN N.Y. STALLION STAKES • FULL SALES RESULTS FROM FIRST NIGHT Belmont Derby Inv. S.-G1 winner Diana S.-G1 winner MR SPEAKER SOMALI LEMONADE Donn H.-G1 winner LEA Man o’ War S-G1 winner IMAGINING 14 Graded SWs This Year were Foaled/Raised at Claiborne, including Grade 1 SWs IMAGINING • LEA • MR SPEAKER • SOMALI LEMONADE • LIDERIS ___________________________________ Watch for 2014 Keeneland September Yearlings • By Such Sires as • WAR FRONT, FLATTER, BLAME, ARCH, PULPIT, HORSE GREELEY, TRAPPE SHOT, STROLL, PROUD CITIZEN, MORE THAN READY, SPEIGHTSTOWN, AFLEET ALEX, CURLIN, QUALITY ROAD, CAPE BLANCO (IRE), LANGFUHR, CITY ZIP, ESKENDEREYA, GHOSTZAPPER Post Office Box 150 Paris, Kentucky 40362-0150 Tel.(859) 233-4252 Fax 987-0008 claibornefarm.com INQUIRIES TO BERNIE SAMS e-mail: [email protected] © ADAM COGLIANESE, PATRICIA MCQUEEN, ADAM MOOSHIAN 2 14-0555.CLB.CLBRaised.SarSp.Aug5.indd 1 The Saratoga Special Tuesday, August8/4/14 5, 3:19 2014 PM here&there... at Saratoga NAME OF THE DAY Miss Metropolitan, Hip 98. The chestnut filly is a half-sister to millionaire True Metropolitan and sells tonight at Fasig-Tipton. NAMES OF THE DAY SUGGESTIONS Hip 87 is a colt by Harlan’s Holiday out of Soloing. How about Guy’s Weekend? Hip 117 is a colt by Street Sense out of Useewhatimsaying. We’d go with Fagedaboudit or maybe Badabing. -

CBO Rpt09-10 Permit Issued with Valuations

City of Frisco Residential New Permits Issued From 5/1/2021 To 5/31/2021 Permit No Date Issued Type and Sub-Type Status Site Address / Parcel No. / Subdiv Contractor Year 2021 Month May B16-4267 5/13/2021 BUILDING SNEW ISSUED 190 TIMBER CREEK LN LENNAR HOMES Description 3902 AC, 4992 SF, SFR / 2 STORY Exp 7/30/2021 A-DD151071 1707 MARKET PLACE BLVD STE 220 Owner LENNAR HOMES Lot 4 Block E ESTATES AT ROCKHILL PHASE I IRVING, TX 75063 (469) 587-5200 B18-00467 5/18/2021 BUILDING SNEW ISSUED 15375 VIBURNUM RD SOUTHGATE HOMES - GARILEN, LLC Description 4299 AC, 5163 SF, SFR / 2 STORY Exp 7/30/2021 A-DD206036 2805 Dallas Parkway, Suite 400 2805 DALLAS PKWY, STE 120 Owner SOUTHGATE HOMES - GARILEN LLC Lot 8 Block B GARILEN PHASE 1B (CFR) Plano, TX 75093 (469) 573-6796 B20-05659 5/20/2021 BUILDING SNEW ISSUED 6790 BARNES DR MHI COVENTRY PLANTATION Description 3091 AC, 3749 SF, 1 STORY Exp 11/16/2021 A-DD221391 7676 Woodway Drive #104 Owner MHI PARTNERSHIP LTD Lot 66 Block A EDGESTONE AT LEGACY PHASE 2 HOUSTON, TX 77063 NORTH (972) 484-6665 B20-05999 5/25/2021 BUILDING SNEW ISSUED 15827 GARDENIA RD LANDON HOMES Description 4617 AC, 5442 SF, 2 STORY Exp 11/21/2021 A-DD267552 4050 W PARK BLVD Owner LANDON HOMES Lot 13 Block L HOLLYHOCK PH 5 PLANO, TX 75093 (214) 619-1077 B21-00043 5/24/2021 BUILDING SNEW ISSUED 12757 LYON ST TSHH, LLC Description 3961AC, 4643 SF, 2 STORY Exp 11/20/2021 A-DD235352 2805 N. -

2005 Triple Crown Nominations

Number HORSE SEX COLOR SIRE DAM TRAINER OWNER BREEDER J. Armando Rodriguez Racing 1 A. Rod Again C CH Awesome Again C J's Leelee Michael J. Maker Sarah Lyn Stables Stable, Inc. 2 Abdaar C CH Hard Spun Marraasi Chad C. Brown Shadwell Stable Shadwell Farm, LLC 3 Abounding Legacy C CH Flashstorm Abounding Truth Ralph E. Nicks Run Hard Stables Northwest Stud Johnston, E. W. and Judy and 4 C DK B Vronsky Allswellthatnswell Donald Warren Old English Rancho Acceptance Riggio, Robert 5 Action Hero C B Street Cry (IRE) Starrer Thomas F. Proctor George Krikorian George Krikorian 6 Al Risala C DK B Pioneerof the Nile Argenta Bob Baffert Zayat Stables, LLC Kristin Mulhall & Vicky Dimitri 7 Alazano C CH More Than Ready Authenicat Dallas Stewart On Our Own Stable LLC Grapestock LLC Mt. Brilliant Farm LLC, Gainesway 8 C CH Malibu Moon Tap Your Heels Chad C. Brown Barouche Stud (Ireland) Ltd. Aldrin Stable (Antony Beck) and LaPenta, 9 Alexa's Spirit C CH Congrats Far and Away Peter D. Pugh James G. Doyle James Doyle Mr. Derrick Smith, Mrs. John 10 C B Galileo (IRE) Dietrich Aidan P. O'Brien Southern Bloodstock Aloft (IRE) Magnier and Mr. Michael Tabor 11 American Pharoah R B Pioneerof the Nile Littleprincessemma Bob Baffert Zayat Stables, LLC Zayat Stables 12 Ami's Flatter C B Flatter Galloping Ami Josie Carroll Ivan Dalos Tall Oaks Farm 13 Another Lemon Drop C DK B/ Lemon Drop Kid Shytoe Lafeet Philip A. Bauer Rigney Racing Avalon Farms, Inc. 14 Apollo Eleven C DK B/ Medaglia d'Oro Moonlightandbeauty Rudy R. -

Irish National Stud: Racing Ahead Cont

SUNDAY, 10 FEBRUARY 2019 NO NEW EI POSITIVES ON SATURDAY IRISH NATIONAL STUD: There have been no new positive cases of equine RACING AHEAD influenzaBincluding those from the yard of Rebecca MenziesBfrom over 700 samples processed so far, the British Horseracing Authority reported on Saturday. In an update on Saturday afternoon, the BHA reported the Animal Health Trust in Newmarket found "no further positive samples" following the six previously detected at Donald McCain's stable. Under the header 'latest information', the BHA's statement read: "The AHT has informed the BHA that it has received approximately 2,100 nasal swabs and tested and reported on 720. So far, other than the six at the yard of Donald McCain already identified, there have been no further positive samples returned. This includes the swabs taken from horses at the yard of Rebecca Menzies. One horse--which tested negative--had previously been identified as suspicious and high risk after testing at a different laboratory. All these horses will remain under close surveillance, analysis of tests from the yard is Lethal Promise, a listed winner in the colours of the ongoing--and testing of the suspicious horses will be repeated." Irish National Stud Racing Club | Racing Post AThe Animal Health Trust have today informed the BHA that by Alayna Cullen the three horses which I had in isolation here at Howe Hills have The Irish National Stud recently launched a Racing Club which returned negative test results for equine flu,@ trainer Rebecca will have six horses to cheer on for the 2019 season. With plans Menzies said in a statement released by the National Trainers to visit big races at Cheltenham and Royal Ascot as well as taking Federation on Saturday. -

Manuel V. City of Joliet: Pursuing a Claim Under the Fourth Amendment

Texas A&M Law Review Volume 5 Issue 1 2018 Manuel v. City of Joliet: Pursuing a Claim Under the Fourth Amendment Lynda Hercules Charleson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/lawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Lynda H. Charleson, Manuel v. City of Joliet: Pursuing a Claim Under the Fourth Amendment, 5 Tex. A&M L. Rev. Arguendo 47 (2018). Available at: https://doi.org/10.37419/LR.V5.Arg.4 This Arguendo (Online) is brought to you for free and open access by Texas A&M Law Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Texas A&M Law Review by an authorized editor of Texas A&M Law Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volume 5 Texas A&M Law Review Arguendo 2018 MANUEL V. CITY OF JOLIET: PURSUING A CLAIM UNDER THE FOURTH AMENDMENT Lynda Hercules Charleson1 I. Introduction In Justice Kagan’s majority opinion in Manuel v. City of Joliet, the Supreme Court held that the Fourth Amendment governs a claim sought under 42 U.S.C.A. § 1983 for unlawful pretrial detention, even after the start of the legal process.2 Following the “broad consensus among the circuit courts,” the Court overturned the Seventh Circuit’s holding that pretrial detention following the start of the legal process was a claim under the Due Process Clause instead of the Fourth Amendment.3 This note will argue that the Court’s majority opinion correctly held that the Fourth Amendment governs a claim for unlawful pretrial detention both before and after the legal process begins, but the Court incorrectly remanded the statute of limitations issue to the lower court. -

Horse Versus Man Looms in Classic

MONDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2017 HORSE VERSUS MAN SIGNIFICANT FORM--AND TALENT--ON DISPLAY IN MISS GRILLO LOOMS IN CLASSIC Significant Form (Creative Cause) crossed the wire first in her Aug. 27 unveiling at Saratoga, only to be disqualified for drifting inward and causing interference into the first turn. She put that all behind her Sunday, producing the same result--minus the antics--and capturing the GIII Miss Grillo S. at Belmont. The gray, a $575,000 OBS April 2-year-old purchase for Stephanie Seymour Brant, tracked the pace and pounced in the stretch, holding off the highly regarded pair of Best Performance (Broken Vow) and Orbolution (Orb) to prevail. After the race, trainer Chad Brown confirmed that the winner likely punched her ticket for the starting gate for the GI Breeders= Cup Juvenile Fillies Turf Nov. 3. AI was really impressed with how she fought back late in the stretch when [Best Performance] challenged her,@ said Brown. AThis win is really encouraging going forward and heading into the Breeders' Cup.@ Cont. p3 Gun Runner may be the only horse standing in the way of a Bob IN TDN EUROPE TODAY Baffert trainee winning the Breeders= Cup Classic | Sarah K. Andrew ARC ANGEL The Week in Review, by Bill Finley Juddmonte’s Enable (GB) (Nathaniel {Ire}), with Frankie Dettori Gun Runner (Candy Ride {Arg}) has earned the right to be in the irons, earned her fifth victory at the highest level in the called the best horse in the U.S. and he will come into the GI G1 Qatar Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe at Chantilly on Sunday for trainer John Gosden. -

News Release ______

News Release _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Contact: Darren Rogers Senior Director, Communications & Media Services Churchill Downs Racetrack (502) 636-4461 (office) (502) 345-1030 (mobile) [email protected] CALIFORNIA INVADER PHANTOM BOSS WINS GRADE III BASHFORD MANOR LOUISVILLE, Ky. (Saturday, June 29, 2019) – Southern California invader Phantom Boss inched clear in the final eighth of a mile to win Saturday’s 118th running of the $125,000 Bashford Manor (Grade III) on closing day at Churchill Downs’ 38-day Spring Meet to beat Rowdy Yates by three-quarters of a length. Ridden by Rafael Bejarano , Phantom Boss ran six furlongs over a fast main track in 1:10.78 for trainer Jorge Periban and owners Bada Beng Racing , Tom Beckerle , Terry Lovingier and Amanda Navarro . Phantom Boss broke alertly from post position No. 1 but he settled nicely behind early leaders Verb and Rowdy Yates. Before the pacesetters hit the first quarter-mile marker in :21.84, Phantom Boss switched to an outside tracking position in third with Snell Yeah just to his inside. Leaving the turn in :45.51, Phantom Boss made a four-wide move to draw even with the bunch. He inched away with a furlong to run and proved to be best. Phantom Boss’ triumph was worth $75,950 and increased his bankroll to $131,850 with a record of two wins and a second in three starts. Previously, he broke his maiden at Santa Anita with an easy 2 ½-length score in a California-bred maiden special weight. Phantom Boss is a 2-year-old son of 2011 Preakness (GI) and 2012 Clark Handicap (GI) winner Shackleford out of the Street Boss mare Bossy Belle. -

Derby Day Weather

Derby Day Weather (The following records are for the entire day...not necessarily race time...unless otherwise noted. Also, the data were taken at the official observation site for the city of Louisville, not at Churchill Downs itself.) Coldest Minimum Temperature: 36 degrees May 4, 1940 and May 4, 1957 Coldest Maximum Temperature: 47 degrees May 4, 1935 and May 4, 1957* (record for the date) Coldest Average Daily Temperature: 42 degrees May 4, 1957 Warmest Maximum Temperature: 94 degrees May 2, 1959 Warmest Average Daily Temperature: 79 degrees May 14, 1886 Warmest Minimum Temperature: 72 degrees May 14, 1886 Wettest: 3.15" of rain May 5, 2018 Sleet has been recorded on Derby Day. On May 6, 1989, sleet fell from 1:01pm to 1:05pm EDT (along with rain). Snow then fell the following morning (just flurries). *The record cold temperatures on Derby Day 1957 were accompanied by north winds of 20 to 25mph! Out of 145 Derby Days, 69 experienced precipitation at some point during the day (48%). Longest stretch of consecutive wet Derby Days (24-hr): 7 (2007-2013) Longest stretch of consecutive wet Derby Days (1pm-7pm): 6 (1989 - 1994) Longest stretch of consecutive dry Derby Days (24-hr): 12 (1875-1886) Longest stretch of consecutive dry Derby Days (1pm-7pm): 12 (1875 - 1886) For individual Derby Day Weather, see next page… Derby Day Weather Date High Low 24-hour Aftn/Eve Weather Winner Track Precipitation Precipitation May 4, 2019 71 58 0.34” 0.34” Showers Country House Sloppy May 5, 2018 70 61 3.15” 2.85” Rain Justify Sloppy May 6, 2017 62 42 -

Prep Races – Kentucky Derby Winners

PREP RACES – KENTUCKY DERBY WINNERS Blue Grass : 23 (11 won both races) KD Year Horse Prep Trainer 2007 Street Sense 2nd Carl Nafzger The following is a listing of active prep races (minimum seven furlongs) and the 1995 Thunder Gulch 4th D. Wayne Lukas number of eventual Kentucky Derby winners who ran in them: 1993 Sea Hero 4th Mac Miller 1991 Strike the Gold 1st Nick Zito Derby 1990 Unbridled 3rd Carl Nafzger Wins Race rd 23 Blue Grass 1987 Alysheba 3 Jack Van Berg nd 23 Champagne 1982 Gato Del Sol 2 Eddie Gregson 23 Florida Derby 1979 Spectacular Bid 1st Bud Delp 20 Hopeful 1972 Riva Ridge 1st Lucien Laurin 20 Wood Memorial 1970 Dust Commander 1st Don Combs 17 Santa Anita Derby st 13 Derby Trial 1968 Forward Pass 1 Henry Forrest 13 Fountain of Youth 1967 Proud Clarion 2nd “Boo” Gentry Jr. 12 San Felipe 1965 Lucky Debonair 1st Frank Catrone 10 San Vicente 1964 Northern Dancer 1st Horatio Luro 8 Breeders’ Futurity st 7 Del Mar Futurity 1963 Chateaugay 1 Jimmy Conway 7 Kentucky Jockey Club 1962 Decidedly 2nd Horatio Luro 6 Arkansas Derby 1959 Tomy Lee-GB 1st Frank Childs 6 Breeders’ Cup Juvenile 1942 Shut Out 1st John Gaver Sr. 6 Los Alamitos Futurity nd 6 Remsen 1941 Whirlaway 2 Ben Jones 3 FrontRunner 1926 Bubbling Over 1st Hebert J. Thompson 3 Holy Bull 1921 Behave Yourself 2nd Hebert J. Thompson 3 Hutcheson 1913 Donerail 2nd T.P. Hayes 3 Louisiana Derby 1911 Meridian 2nd Albert Ewing 3 Rebel 3 Robert B. Lewis Breeders’ Cup Juvenile : 6 (2 won both races) 2 Arlington-Washington Futurity KD Year Horse Prep Trainer st 2 Bay Shore 2016 -

Times – Kentucky Derby ¼ Mile – Slowest

TIMES – KENTUCKY DERBY ¼ MILE – SLOWEST No. Year Horse Finish Split ¼ MILE – FASTEST 1. 1899 His Lordship 4th :25.75 2. 1898 Lieber Karl 2nd :25.50 No. Year Horse Finish Split st th 2. 1901 His Eminence 1 :25.50 1. 1981 Top Avenger 19 :21.80 th th 2. 1903 Woodlake b 5 :25.50 2. 1975 Bombay Duck 15 :22.00 st th 2. 1905 Agile 1 :25.50 3. 1986 Groovy 16 :22.20 th th 6. 1896 First Mate 4 :25.00 3. 1968 Kentucky Sherry 5 :22.20 th 3. 1967 Flag Raiser 8th :22.20 6. 1904 Spanish Chestnut 16 :22.28 6. 1908 Bodemeister 2nd :22.32 6. 2001 Songandaprayer 13 th :22.25 6. 1909 Honour and Glory 18 th 7. 2005 Spanish Chestnut 16 th :22.28 :22.34 8. 2012 Bodemeister 2nd :22.32 9. 1996 Honour and Glory 18 th :22.34 ¼ MILE – SLOWEST LAST 30 YEARS (1987) rd 1. 1997 Free House 3 :23.57 ¼ MILE – FASTEST LAST 30 YEARS (1987) 1. 2001 Songandaprayer 13 th :22.25 ½ MILE – SLOWEST No. Year Horse Finish Split ½ MILE – FASTEST 1. 1899 Manuel 1st :51.25 2. 1901 His Eminence 1st :51.00 No. Year Horse Finish Split rd th 2. 1903 Woodlake b 3 :51.00 1. 2001 Songandaprayer 13 :44.86 nd th 4. 1898 Lieber Karl 2 :50.25 2. 1981 Top Avenger 19 :45.20 th th 5. 1908 Banridge 5 :50.20 2. 1986 Groovy 16 :45.20 st th 6. 1905 Agile 1 :50.00 4.