Sumac Berries: Citrus in a Seed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Great Food, Great Stories from Korea

GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIE FOOD, GREAT GREAT A Tableau of a Diamond Wedding Anniversary GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS This is a picture of an older couple from the 18th century repeating their wedding ceremony in celebration of their 60th anniversary. REGISTRATION NUMBER This painting vividly depicts a tableau in which their children offer up 11-1541000-001295-01 a cup of drink, wishing them health and longevity. The authorship of the painting is unknown, and the painting is currently housed in the National Museum of Korea. Designed to help foreigners understand Korean cuisine more easily and with greater accuracy, our <Korean Menu Guide> contains information on 154 Korean dishes in 10 languages. S <Korean Restaurant Guide 2011-Tokyo> introduces 34 excellent F Korean restaurants in the Greater Tokyo Area. ROM KOREA GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIES FROM KOREA The Korean Food Foundation is a specialized GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIES private organization that searches for new This book tells the many stories of Korean food, the rich flavors that have evolved generation dishes and conducts research on Korean cuisine after generation, meal after meal, for over several millennia on the Korean peninsula. in order to introduce Korean food and culinary A single dish usually leads to the creation of another through the expansion of time and space, FROM KOREA culture to the world, and support related making it impossible to count the exact number of dishes in the Korean cuisine. So, for this content development and marketing. <Korean Restaurant Guide 2011-Western Europe> (5 volumes in total) book, we have only included a selection of a hundred or so of the most representative. -

STAR SWEETENERS the Best of the Naturals

STAR SWEETENERS The Best of the Naturals Become sugar savvy! The term "natural" as applied to sweeteners, can mean many things. The sweeteners recommended below will provide you with steady energy because they take a long time to digest. Natural choices offer rich flavors, vitamins and minerals, without the ups and downs of refined sugars. Sugar substitutes were actually the natural sweeteners of days past, especially honey and maple syrup. Stay away from man-made artificial sweeteners including aspartame and any of the "sugar alcohols" (names ending in ol). In health food stores, be alert for sugars disguised as "evaporated cane juice" or "can juice crystals." These can still cause problems, regardless what the health food store manager tells you. My patients have seen huge improvements by changing their sugar choices. Brown rice syrup. Your bloodstream absorbs this balanced syrup, high in maltose and complex carbohydrates, slowly and steadily. Brown rice syrup is a natural for baked goods and hot drinks. It adds subtle sweetness and a rich, butterscotch-like flavor. To get sweetness from starchy brown rice, the magic ingredients are enzymes, but the actual process varies depending on the syrup manufacturer. "Malted" syrups use whole, sprouted barley to create a balanced sweetener. Choose these syrups to make tastier muffins and cakes. Cheaper, sweeter rice syrups use isolated enzymes and are a bit harder on blood sugar levels. For a healthy treat, drizzle gently heated rice syrup over popcorn to make natural caramel corn. Store in a cool, dry place. Devansoy is the brand name for powdered brown rice sweetener, which contains the same complex carbohydrates as brown rice syrup and a natural plant flavoring. -

Selecting, Preparing, and Canning Fruit and Fruit Products

Complete Guide to Home Canning Guide 2 Selecting, Preparing, and Canning Fruit and Fruit Products 2-2 Guide 2 Selecting, Preparing, and Canning Fruit and Fruit Products Table of Contents Section .......................................................................................................................Page 2 General ...............................................................................................................................2-5 Preparing and using syrups ..................................................................................................2-5 Fruit and Fruit Products Apple butter ........................................................................................................................2-6 Apple juice ..........................................................................................................................2-6 Apples—sliced .....................................................................................................................2-7 Applesauce .........................................................................................................................2-7 Spiced apple rings ...............................................................................................................2-8 Spiced crab apples ...............................................................................................................2-9 Apricots—halved or sliced ....................................................................................................2-9 Berries—whole -

Za'atar-Spiced Beet Dip with Goat Cheese by Adapted by Laura and Alan Rabishaw, Inspired by YOTAM OTTOLENGHI

Za'atar-Spiced Beet Dip with Goat Cheese By Adapted by Laura and Alan Rabishaw, inspired by YOTAM OTTOLENGHI Ingredients 4 medium beets (approximately 1 lb), trimmed —OR Use a product like LOVE’s Beets precooked to skip STEP 1 below 2 small garlic cloves, minced 1 small hot pepper, seeded and minced 2/3 cup plain Greek yogurt 2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil 1 tablespoons date syrup 2tsp + za’atar Salt 1/4 cup roasted pistachios, chopped 2 tablespoons goat cheese, crumbled 2 scallions, thinly slice Pita or Crunchy Vegetables, for serving Step 1 Preheat the oven to 350°. Put the beets in a small roasting pan and add 1/4 cup of water. Cover with foil and bake for about 1 hour, until tender. Let cool slightly. Step 2 Peel the beets, cut into wedges and transfer to a food processor. Add the garlic, chile and yogurt and pulse until blended. Add the olive oil, date syrup and za’atar and puree. Season with salt. Scrape into a wide, shallow bowl. Scatter the pistachios, goat cheese and scallions on top and serve with bread. Roasted Beets with Chick Peas Various Recipes Adapted by Laura and Alan Rabishaw Ingredients 4 medium beets (approximately 1 lb), trimmed —OR Use a product like LOVE’s Beets precooked to skip STEP 1 below 1 can Chick Peas, drained and rinsed 2 tbls of your favorite middle eastern spice blend (za’tar, harissa powder, ras al hanout, hawaij or other. You can buy premixed, or google for recipes) Salt and pepper to taste Extra-virgin olive oil Step 1 Preheat the oven to 350°. -

Native Nebraska Woody Plants

THE NEBRASKA STATEWIDE ARBORETUM PRESENTS NATIVE NEBRASKA WOODY PLANTS Trees (Genus/Species – Common Name) 62. Atriplex canescens - four-wing saltbrush 1. Acer glabrum - Rocky Mountain maple 63. Atriplex nuttallii - moundscale 2. Acer negundo - boxelder maple 64. Ceanothus americanus - New Jersey tea 3. Acer saccharinum - silver maple 65. Ceanothus herbaceous - inland ceanothus 4. Aesculus glabra - Ohio buckeye 66. Cephalanthus occidentalis - buttonbush 5. Asimina triloba - pawpaw 67. Cercocarpus montanus - mountain mahogany 6. Betula occidentalis - water birch 68. Chrysothamnus nauseosus - rabbitbrush 7. Betula papyrifera - paper birch 69. Chrysothamnus parryi - parry rabbitbrush 8. Carya cordiformis - bitternut hickory 70. Cornus amomum - silky (pale) dogwood 9. Carya ovata - shagbark hickory 71. Cornus drummondii - roughleaf dogwood 10. Celtis occidentalis - hackberry 72. Cornus racemosa - gray dogwood 11. Cercis canadensis - eastern redbud 73. Cornus sericea - red-stem (redosier) dogwood 12. Crataegus mollis - downy hawthorn 74. Corylus americana - American hazelnut 13. Crataegus succulenta - succulent hawthorn 75. Euonymus atropurpureus - eastern wahoo 14. Fraxinus americana - white ash 76. Juniperus communis - common juniper 15. Fraxinus pennsylvanica - green ash 77. Juniperus horizontalis - creeping juniper 16. Gleditsia triacanthos - honeylocust 78. Mahonia repens - creeping mahonia 17. Gymnocladus dioicus - Kentucky coffeetree 79. Physocarpus opulifolius - ninebark 18. Juglans nigra - black walnut 80. Prunus besseyi - western sandcherry 19. Juniperus scopulorum - Rocky Mountain juniper 81. Rhamnus lanceolata - lanceleaf buckthorn 20. Juniperus virginiana - eastern redcedar 82. Rhus aromatica - fragrant sumac 21. Malus ioensis - wild crabapple 83. Rhus copallina - flameleaf (shining) sumac 22. Morus rubra - red mulberry 84. Rhus glabra - smooth sumac 23. Ostrya virginiana - hophornbeam (ironwood) 85. Rhus trilobata - skunkbush sumac 24. Pinus flexilis - limber pine 86. Ribes americanum - wild black currant 25. -

Native Oak Chapparal Species Plant Lists

NATIVE OAK CHAPPARAL SPECIES PLANT LISTS Scientific Name Common Name Plant Type Height Bloom Period Picture Achillea millefolium Common yarrow Forb, PF 8-6” Summer (butterflies, bees), DF, DR Bromus carinatus Lemon’s Grass 7.5-32” Spring needlegrass Amelanchier alnifolia Western Shrub, PF 5-20’ Mid Spring serviceberry (butterflies, bees), DT Arbutus menziesii Pacific madrone Evergreen 15-100’ Spring Tree, PF (butterflies, moths, hummingbir ds), DT Balsamorhiza sagittata Arrowleaf Forb, PF 8-36” Mid-Late balsamroot Spring Bromus carinatus California Grass 1-5’ Spring brome Bromus laevipes Chinook brome Grass 5’ Spring - Summer Resource Factsheets: Plants 1 NATIVE OAK CHAPPARAL SPECIES Castilleja varieties Indian paintbrush Forb, PF 2’ Spring - Summer Ceanothus cuneatus Buckbrush Shrub, PF 3-12’ Late spring Ceanothus integerrimus Deerbrush Shrub, PF 3-13’ Spring-Summer (bees) Cercocarpus Mountain Shrub 8-20’ Winter, Spring mahogany Collomia grandiflora Grand collomia Forb, PF 18” Mid Spring – Mid Summer Corylus cornuta California Shrub 3-50’ Spring-Fall hazelnut Dichelostemma Blue dicks Forb, PF 6-27” Early Summer capitatum Elymus glaucus Blue wildrye Grass 1-5’ Summer Eschscholzia californica California poppy Forb, PF, 6-16” Spring-Summer DT Resource Factsheets: Plants 2 NATIVE OAK CHAPPARAL SPECIES Festuca californica California fescue Grass, DT 1-4’ Spring, Winter Festuca occidentalis Western fescue Grass, DT 3-4’ Spring Garrya fremontii Bearbrush Shrub, PF, 9-13’ DT Iris chrysophylla Yellowleaf iris Forb, PF 2-8” Late Spring (butterflies, -

The Map of Maple

the map of maple intensity maple maple toasted baked apple toasted nuts University of VermontUniversity of © brioche roasted marshmallow golden sugar burnt sugar crème brûlée caramel coffee milky fresh butter melted butter condensed milk butterscotch confectionary light brown sugar dark brown sugar molasses toffee spice vanilla cinnamon nutmeg mixed spices fruity raisins prunes aroma and flavor and aroma orange grapefruit peach apricot mango raw nuts floral honey floral blend earthy grassy hay oats mushroom others praline dark chocolate bourbon soy sauce spiced meat leather mineral notes maple sweetness balance intensity taste smooth mineral thin syrupy thick mouthfeel tasting maple syrup The map of maple is a sensory tool, allowing you to explore all the wondrous possibilities of Vermont maple syrup. Here are some hints for tasting on your own. Smell the syrup before tasting. Try to identify any distinct aromas. Take a look at the list of aroma and flavor descriptors as a guide. Take a small sip of the syrup. Move the syrup in your mouth briefly, and feel the texture. See the mouthfeel section for suggestions. Then, evaluate the taste characteristics. See the taste section for suggestions. For all the sensory properties evaluated, always try to asses the quality, quantity and balance of the descriptors identified. Consider the flavor with another sip. See if the sensory “families” help you place the aroma and flavor of the syrup, allowing & you to identify and describe each particular maple syrup. If possible, taste and share your reactions with a friend. Sometimes tasting and talking with others can help your descriptions. why taste and tell? Maple syrup is an old-fashioned yet long-lived taste of Vermont. -

To Start with Pasta

FOOD MENU - 2021 8 Raffles Avenue, #01-13D, Singapore 039802 To start with Plain Fries $10 Pizza Fries $18 Straight cut fries in salt serve with house dip. The one that make us famous fries, beef peperoni, cheese sauce. Truffle Fries $15 Straight cut fries in truffle oil and dried oregano, parmesan Mexicano Taco Fries $18 cheese serve with our tartar sauce. Fries seasoned with taco flavor, salsa served with nacho cheese dip. Choice of beef or chicken toppings. $15 Salted Egg Fries $10 Salted egg seasoned fries, served with sweet and spicy salted Fish Skin egg sauce. Umami flavor fish skin serve with sweet and spicy sauce. Nachos $14 Calamari $16 Tortilla chips with mango salsa, nacho cheese dip. Buttered squid rings serve with tartar sauce and lemon wedge. $18 Shripm Gambas $18 Saute shrimp in buttery garlic and onion serve with salsa or Spicy Buffalo Wings house salad, grilled lime. Spicy or regular buffalo wings satisfy with beer match, served with tartar sauce. Har Cheong Kai $15 Salted Egg Chicken Wings $18 Well known prawn paste wings. Salted eggs, chicken wings, satisfy with beer match. Pasta Aglio Olio (Shrimp or Chicken) $20 Creamy Chicken Mushroom $20 Spaghetti pasta tossed in garlic, chilli flakes topped with Penne pasta in creamy sauce mushroom. Topped with grilled parmesan and basil. chicken breast, parmesan and parsley. Seafood Pasta $20 Bolognese Pasta $20 Spaghetti pasta and squid ring king prawns, tossed in our Ground beef in marinara sauce. homemade marinara sauce, topped with shave parmesan chopped parsley. Chicken Alfredo (Spaghetti/Penne) $20 Fettuccine pasta/penne, cream, garlic, chicken breast, parsley, Classic Carbonara $20 parmesan and chives on top. -

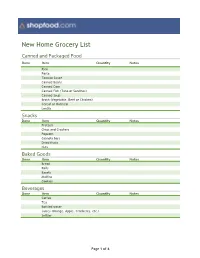

New Home Grocery List

New Home Grocery List Canned and Packaged Food Done Item Quantity Notes Rice Pasta Tomato Sauce Canned Beans Canned Corn Canned Fish (Tuna or Sardines) Canned Soup Broth (Vegetable, Beef or Chicken) Cereal or Oatmeal Lentils Snacks Done Item Quantity Notes Pretzels Chips and Crackers Popcorn Granola bars Dried fruits Nuts Baked Goods Done Item Quantity Notes Bread Rolls Bagels Muffins Cookies Beverages Done Item Quantity Notes Coffee Tea Bottled water Juices (Orange, Apple, Cranberry, etc.) Seltzer Page 1 of 6 New Home Grocery List Spices Done Item Quantity Notes Sea Salt Black Pepper Crushed Red Pepper Paprika Oregano Basil Parsley Rosemary Garlic Powder Cilantro Chili Powder Cumin Ginger Cinnamon Turmeric Condiments Done Item Quantity Notes Olive Oil Cooking Oil (vegetable, canola etc.) Vinegar Ketchup Mustard Mayo Soy Sauce Hot Sauce Salad Dressing Pickles Worcestershire Sauce BBQ Sauce Steak Sauce Maple Syrup Honey Jam or Jelly Nut Butter (Peanut, Almond, etc.) Page 2 of 6 New Home Grocery List Frozen Food Done Item Quantity Notes Mixed Vegetables Fruit Meat (Burgers, Chicken nuggets, etc.) Veggie Burgers Pizza French Fries Waffles Pancakes Ice-cream Fresh Food Done Item Quantity Notes Apples Oranges Bananas Berries Tangerines Grapes Peaches Plums Tomatoes Cucumbers Avocados Lemon Lime Lettuce Spinach Green Beans Broccoli Asparagus Beets Celery Carrots Potatoes Mushrooms Peppers Onions Garlic Page 3 of 6 New Home Grocery List Meat, Poultry, and Seafood Done Item Quantity Notes Chicken Fish Shrimp Steak Ground Beef Ground Turkey Eggs -

A Carrot by Any Other Name… New Looks at Your Old Co-Op by Shannon Szymkowiak, Promotions & Education Manager & WFC Owner

20 WINTER 2013 GARBANZO GAZETTE back 40 special items in your produce department by Claire Musech, Produce Buyer/ Receiver & WFC Owner You may have already noticed the for flowers, and you receive and 15% have a gorgeous assortment of Poin- bright, new addition to your Co-op—it’s discount if you are a WFC Owner! Place settias, Norfolk Pines, Frosty Ferns, fresh flower bouquets and plants! them at the Customer Service Counter, Rosemary Cones, Golden Cypress and I have had the pleasure of working with or with anyone in the Produce Depart- Silver Bush set to arrive on December Koehler and Dramm Wholesale Florist ment or you can just call it in. 13th. Guarantee your first choice by put- in Minneapolis to bring you beautiful ting in a special order with the Produce We are also working on sourcing local and affordable cut flower bouquets, Department today as quantities are and regional fall mums from the Amish arrangements and plants. We have limited. and an assortment of local hanging been able to provide a unique selection baskets in the spring. This is a small Add a distinguishing touch to your of house plants ranging from traditional but exciting step towards our store goal Holiday gathering by arriving with ones like Ivy and Pathos to the unusual of having 20 percent of all products a Co-op made fruit and vegetable tray varieties like Venus fly trap and sold be LOCAL by the year 2020! or fruit and gift basket. We are happy Cypress. Whether you are choosing to take special requests within 48 hours a gift to brighten someone’s day Everyone loves flowers for the Holidays. -

Vegetation Mapping of the Mckenzie Preserve at Table Mountain and Environs, Southern Sierra Nevada Foothills, California

Vegetation Mapping of the McKenzie Preserve at Table Mountain and Environs, Southern Sierra Nevada Foothills, California By Danielle Roach, Suzanne Harmon, and Julie Evens Of the 2707 K Street, Suite 1 Sacramento CA, 95816 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To Those Who Generously Provided Support and Guidance: Many groups and individuals assisted us in completing this report and the supporting vegetation map/data. First, we expressly thank an anonymous donor who provided financial support in 2010 for this project’s fieldwork and mapping in the southern foothills of the Sierra Nevada. We also are thankful of the generous support from California Department of Fish and Game (DFG) in funding 2008 field survey work in the region. We are indebted to the following additional staff and volunteers of the California Native Plant Society who provided us with field surveying, mission planning, technical GIS, and other input to accomplish this project: Jennifer Buck, Andra Forney, Andrew Georgeades, Brett Hall, Betsy Harbert, Kate Huxster, Theresa Johnson, Claire Muerdter, Eric Peterson, Stu Richardson, Lisa Stelzner, Aaron Wentzel, and in particular, Kendra Sikes. To Those Who Provided Land Access: Joanna Clines, Forest Botanist, USDA Forest Service, Sierra National Forest Ellen Cypher, Botanist, Department of Fish and Game, Region 4 Mark Deleon, Supervising Ranger, Millerton Lake State Recreation Area Bridget Fithian, Mariposa Program Manager, Sierra Foothill Conservancy Coke Hallowell, Private landowner, San Joaquin River Parkway & Conservation Trust Wayne Harrison, California State Parks, Central Valley District Chris Kapheim, General Manager, Alta Irrigation District Denis Kearns, Botanist, Bureau of Land Management Melinda Marks, Executive Officer, San Joaquin River Conservancy Nathan McLachlin, Scientific Aid, Department of Fish and Game, Region 4 Eddie and Gail McMurtry, private landowners Chuck Peck, Founder, Sierra Foothill Conservancy Kathyrn Purcell, Research Wildlife Ecologist, San Joaquin Experimental Range, USDA Forest Service Carrie Richardson, Senior Ranger, U.S. -

Muhammara (Roasted Red Pepper and Walnut Dip) Makes About 2 Cups

PITTSBURGH’S HOME FOR KITCHENWARES 412.261.5513 | 1725 Penn Avenue | Pittsburgh, PA 15222 Muhammara (Roasted Red Pepper and Walnut Dip) Makes about 2 cups This muhammara dip is made of roasted red peppers, earthy toasted walnuts, and freshly toasted bread- crumbs. All of these savory items are blended together with a few additional ingredients and one specialty item -- pomegranate molasses. The pomegranate molasses gives a special sweet and tangy depth to the dip -- so delicious! Ingredients: 1 tablespoon lemon juice 3 red peppers, halved and roasted 5 tablespoons olive oil 1 tablespoon olive oil for roasting peppers. 2 tablespoons pomegranate molasses* 1/2 cup walnuts, lightly toasted 1 teaspoon Kosher salt 1/2 cup fine, freshly grated bread crumbs 1/4 teaspoon cayenne pepper (use dry bread, pulse in food processor to create a fine crumb, toast in pan with one tablespoon Optional Garnishes: olive oil until just crispy) 10 walnut halves 2 tablespoons tomato paste Fresh parsley 1 clove garlic, minced Directions: 1. Preheat the oven to 450 degrees F. 2. Halve the peppers, de-seed, brush with olive oil, and place cut side down on a baking sheet. Roast the peppers until softened. Achieve some char on the peppers by broiling for a few minutes. 3. Place the roasted red peppers in a bowl, and cover for 10 minutes. After the peppers have cooled, carefully peel the skins o. 4. While the peppers are roasting, toast the walnuts. In a small dry skillet, toast the walnuts until just fragrant. Set the walnuts aside. 5. In the same skillet, toss the bread crumbs with one tablespoon of olive oil.