'Presence' in Absentia: Experiencing Performance As Documentation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Take 2 Dance Band Current Song List

TAKE 2 DANCE BAND CURRENT PLAYLIST 24K MAGIC BRUNO MARS 25 OR 6 TO 4 CHICAGO AFRICA TOTO AIN’T IT FUN PARAMORE AIN’T NO MOUNTAIN HIGH ENOUGH GAYE & TERRELL AIN’T NO OTHER MAN CHRISTINA AGUILERA AIN’T NOBODY CHAKA KHAN AIN’T THAT A KICK IN THE HEAD DEAN MARTIN AMERICAN GIRL TOM PETTY ANOTHER ONE BITES THE DUST QUEEN ANY WAY YOU WANT IT JOURNEY ARE YOU GONNA BE MY GIRL JET AT LAST ETTA JAMES ATTENTION CHARLIE PLUTH BABY ONE MORE TIME BRITNEY SPEARS BACK IN LOVE AGAIN L.T.D. BEAT IT MICHAEL JACKSON BEST OF MY LOVE THE EMOTIONS BILLIE JEAN MICHAEL JACKSON BLACK CAT JANET JACKSON BLURRED LINES ROBIN THICKE BOOGIE OOGIE OOGIE TASTE OF HONEY BORDERLINE MADONNA BORN TO BE WILD STEPPENWOLF BROKENHEARTED KARMIN CAKE BY THE OCEAN DNCE CALIFORNIA GIRLS KATY PERRY CALIFORNIA LOVE 2PAC CALL ME MAYBE CARLY RAE JEPSEN CALLING BATON ROUGE GARTH BROOKS CAN’T STOP THIS FEELING JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE CAR WASH ROLLS ROYCE CELEBRITY SKIN HOLE CLOSER CHAINSMOKERS COME OUT & PLAY OFFSPRING CRAZY IN LOVE BEYONCE DA YA THINK I’M SEXY STEWART & DNCE DANCE TO THE MUSIC SLY/FAMILY STONE DER KOMMISSAR AFTER THE FIRE DIE YOUNG KE$HA DON’T PHUNK WITH MY HEART BLACKEYED PEAS DON’T STOP BELIEVING JOURNEY DREAMS FLEETWOOD MAC ESCAPADE JANET JACKSON EVERYBODY BACKSTREET BOYS EVERYBODY WANTS YOU BILLY SQUIRE FAITHFULLY FAME DAVID BOWIE FEEL FOR YOU CHAKA KHAN FEELS CALVIN HARRIS FINALLY CECE PENISTON FINESSE BRUNO MARS FORGET YOU CEE LO GREEN GAME OF LOVE SANTANA GENIE IN A BOTTLE CHRISTINA AUGILERA GET DOWN ON IT KOOL & THE GANG GET INTO THE GROOVE MADONNA GET LUCKY DAFT PUNK GIRLS JUST WANNA HAVE FUN CINDI LAUPER GOOD VIBRATIONS MARKY MARK GOT TO BE REAL CHERYL LYNN GROOVE LINE HEATWAVE H.O.L.Y. -

Michael Jackson

Chart - History Singles All chart-entries in the Top 100 Peak:1 Peak:1 Peak: 1 Germany / United Kindom / U S A Michael Jackson No. of Titles Positions Michael Joseph Jackson (August 29, 1958 – Peak Tot. T10 #1 Tot. T10 #1 June 25, 2009) was an American singer, 1 48 20 2 842 117 9 songwriter and dancer. Dubbed the "King of 1 65 44 7 838 158 16 Pop", he is regarded as one of the most 1 51 30 13 732 183 37 significant cultural icons of the 20th century and is also regarded as one of the greatest 1 72 47 17 2.412 458 62 entertainers of all time. Jackson's contributions to music, dance, and fashion, along with his publicized personal life, made him a global figure in popular culture for over four decades. ber_covers_singles Germany U K U S A Singles compiled by Volker Doerken Date Peak WoC T10 Date Peak WoC T10 Date Peak WoC T10 1 Got To Be There 02/1972 5 11 6910/1971 4 14 2 Rockin' Robin 05/1972 3 14 6803/1972 2 13 3 I Wanna Be Where You Are 05/1972 16 11 4 Ben 11/1972 7 17 4708/1972 1 1 16 5 Ain't No Sunshine 08/1972 8 13 3 6 With A Child's Heart 05/1973 50 7 7 We're Almost There 08/1981 46 4 03/1975 54 8 8 Just A Little Bit Of You 06/1975 23 12 9 Ease On Down The Road 11/1978 45 7 09/1978 41 9 ► Michael Jackson & Diana Ross 10 You Can't Win 02/1979 81 3 11 Don't Stop 'til You Get Enough 11/1979 13 28 09/1979 3 19 5607/1979 1 1 21 12 Rock With You 03/1980 58 10 02/1980 7 15 2911/1979 1 4 24 13 Off The Wall 11/1979 7 12 1202/1980 10 17 14 She's Out Of My Life 05/1980 3 11 4204/1980 10 16 15 Girlfriend 07/1980 41 5 16 One Day In Your Life 05/1981 1 2 16 6 04/1981 55 7 17 The Girl Is Mine 01/1983 53 4 11/1982 8 12 21011/1982 2 18 ► Michael Jackson & Paul McCartney 18 Billie Jean 02/1983 2 40 1101/1983 1 1733 701/1983 1 25 11 19 Beat It 05/1983 2 35 741004/1983 3 22 02/1983 1 3 25 20 Wanna Be Startin' Something 07/1983 16 11 06/1983 8 12 1605/1983 5 15 21 Happy (Love Theme From "Lady Sings The Blues" ) 07/1983 52 4 22 Human Nature 10/1983 64 3 07/2009 62 2 07/1983 7 14 4 23 P.Y.T. -

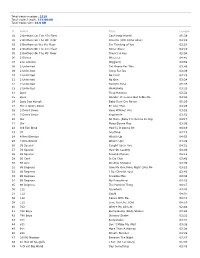

Total Tracks Number: 2218 Total Tracks Length: 151:00:00 Total Tracks Size: 16.0 GB

Total tracks number: 2218 Total tracks length: 151:00:00 Total tracks size: 16.0 GB # Artist Title Length 01 2 Brothers On The 4Th Floor Can't Help Myself 05:39 02 2 Brothers On The 4th Floor Dreams (Will Come Alive) 04:19 03 2 Brothers on the 4th Floor I'm Thinking of You 03:24 04 2 Brothers On The 4Th Floor Never Alone 04:10 05 2 Brothers On The 4th Floor There's A Key 03:54 06 2 Eivissa Oh La La 04:41 07 2 In a Room Wiggle It 03:59 08 2 Unlimited Get Ready For This 03:40 09 2 Unlimited Jump For Joy 03:39 10 2 Unlimited No Limit 03:28 11 2 Unlimited No One 03:24 12 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 05:36 13 2 Unlimited Workaholic 03:33 14 2pac Thug Mansion 03:32 15 2pac Wonder If Heaven Got A Ghetto 04:34 16 2pac Daz Kurupt Baby Dont Cry Remix 05:20 17 Three Doors Down Be Like That 04:25 18 3 Doors Down Here Without You 03:53 19 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 03:52 20 3lw No More (Baby I'm Gonna Do Rig 04:17 21 3lw Playa Gonna Play 03:06 22 3rd Eye Blind How Is It Gonna Be 04:10 23 3T Anything 04:15 24 4 Non Blondes What's Up 04:55 25 4 Non Blonds What's Up? 04:09 26 38 Special Caught Up In You 04:25 27 38 Special Hold On Loosely 04:40 28 38 Special Second Chance 04:12 29 50 Cent In Da Club 03:42 30 50 cent Window Shopper 03:09 31 98 Degrees Give Me One More Night (Una No 03:23 32 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 03:43 33 98 Degrees Invisible Man 04:38 34 98 Degrees My Everything 04:28 35 98 Degrees The Hardest Thing 04:27 36 112 Anywhere 04:03 37 112 Cupid 04:07 38 112 Dance With Me 03:41 39 112 Love You Like I Did 04:16 40 702 Where My Girls At 02:44 -

Brian Friedman Television

Brian Friedman Television: I'm a Celebrity Get Me Out Of Celebrity ITV Here AMERICA'S GOT TALENT 4, Consulting Producer & NBC 5, & 6 Choreographer Nicki Minaj, Flo Rida & David Consulting Producer & Guetta "Where Them Girls At" Choreographer Karmin "Broken Hearted" & Consulting Producer & "Hello" Choreographer Cobra Starship ft. Sabi "You Consulting Producer & Make Me Feel" Choreographer Patti LaBelle "You're All I Consulting Producer & Need" Choreographer Stevie Wonder "Higher Consulting Producer & Ground" Choreographer Lionel Richie & Fighting Consulting Producer & Gravity "Dancing On The Choreographer Ceiling" Sarah Brightman & Jackie Consulting Producer & Evancho "Time To Say Choreographer Goodbye" Donna Summer & Prince Consulting Producer & Poppycock "Last Dance" Choreographer LeAnn Rhimes "Give" Consulting Producer & Choreographer SO YOU THINK YOU CAN Judge & Choreographer FOX DANCE AMERICAN IDOL Creative Director FOX The Wanted "Glad You Came" Creative Director DANCING WITH THE STARS Creative Director & ABC Choreographer Macy's Stars of Dance "Neon" Creative Director & Choreographer SUBURGATORY Guest Star (Serge) ABC AGENT CARTER Choreographer THE VOICE AUSTRALIA Creative Director THE VOICE Creative Director ABC Justin Bieber "Boyfriend" Creative Director The Wanted "Chasing The Creative Director ABC Sun" THE X FACTOR SEASONS 1 Supervising Producer & FOX & 2 Choreographer Nicole Scherzinger "Pretty" Creative Director LeAnne Rhimes "How Do I Creative Director Live" Little Big Town "Pontoon" Creative Director Demi Lovato "Give Your -

Digitization Project for the Center for Research on Concepts and Cognition Prepared By: Wen Nie Ng

Hofstadter’s VHS – Digitization Documentation Last edited: 10/20/2017 v2.2 Digitization Project for The Center for Research on Concepts and Cognition Prepared by: Wen Nie Ng This video digitization project is initiated by Jian Liu while managed by Wen Nie Ng to provide public access to Douglas Hofstadter’s series of five public symposia on IUScholarWorks. This document contains the digitization process, metadata scheme, and technical details of this project for future reference. I owe thanks to Kara Alexander, Jon Cameron, Richard Higgins, and Jian Liu for guidance and assistance provided. If you need further clarification on this document, please do not hesitate to email Wen at [email protected] In this document: I. Digitization manual • Digitizing VHS to digital format • Exporting media • Conversion of VHS to DVD II. Technical Details III. Hofstadter’s Collection Metadata Application Profile • Data Input for each of video elements used on IUScholarWorks a. id b. collection c. dc:title d. dc.contributor.author e. dc.publisher f. dc.subject.lcsh g. dc.description h. dc.language.iso i. dc.type IV. References Page 1 of 12 Hofstadter’s VHS – Digitization Documentation Last edited: 10/20/2017 v2.2 Digitizing VHS to digital format 1. Open Adobe Premiere and start with New Project 2. Name the project and browse to save the project at preferable location. All the other settings will be defaulted as shown in picture below. Page 2 of 12 Hofstadter’s VHS – Digitization Documentation Last edited: 10/20/2017 v2.2 3. You will see the following screen for Sequence presets. -

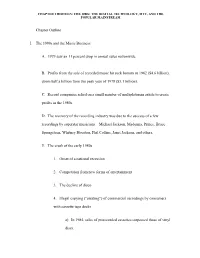

Chapter Outline

CHAPTER THIRTEEN: THE 1980s: THE DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY, MTV, AND THE POPULAR MAINSTREAM Chapter Outline I. The 1980s and the Music Business A. 1979 saw an 11 percent drop in annual sales nationwide. B. Profits from the sale of recorded music hit rock bottom in 1982 ($4.6 billion), down half a billion from the peak year of 1978 ($5.1 billion). C. Record companies relied on a small number of multiplatinum artists to create profits in the 1980s. D. The recovery of the recording industry was due to the success of a few recordings by superstar musicians—Michael Jackson, Madonna, Prince, Bruce Springsteen, Whitney Houston, Phil Collins, Janet Jackson, and others. E. The crash of the early 1980s 1. Onset of a national recession 2. Competition from new forms of entertainment 3. The decline of disco 4. Illegal copying (“pirating”) of commercial recordings by consumers with cassette tape decks a) In 1984, sales of prerecorded cassettes surpassed those of vinyl discs. CHAPTER THIRTEEN: THE 1980s: THE DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY, MTV, AND THE POPULAR MAINSTREAM F. New technologies of the 1980s 1. Digital sound recording and five-inch compact discs (CDs) 2. The first CDs went on sale in 1983, and by 1988, sales of CDs surpassed those of vinyl discs. 3. New devices for producing and manipulating sound: a) Drum machines b) Sequencers c) Samplers d) MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface) G. Music Television (MTV) 1. Began broadcasting in 1981 2. Changed the way the music industry operated, rapidly becoming the preferred method for launching a new act or promoting a superstar’s latest release. -

“If I Die Tomorrow, God Is Still in Control.”

Beaumont Neighborhood Magazine March 2016 “If I die tomorrow, God is still in control.” By Tejaswini Sudhaker (Teja) Photos submitted by Janet Bunge Why am I blessed? I am blessed because I have Erdheim-Chester* disease. I am blessed because I have Histiocytic Sarcoma cancer. I am blessed for this rarity, this part of me that makes people listen. I am blessed because despite everything, my smile never fades. And while the cells in my body rebel against the rules of nature, I am blessed to rebel against what everyone says about sickness. I am blessed to have the spots on my skin and the ache in my bones. I am blessed that they mark me, like a tattoo, and they tell me that I am strong. They tell me that I have made it this far. I am blessed because they tell me to keep going. I am blessed to have this new house, and these new neighbors. I am blessed because even after twenty six years of memories, I can still remember what new feels like. I can still remember. I am blessed to travel. I am blessed to see new things, and meet new people, even if it is for a reason that many may disdain. I am blessed because I can still see the beauty in the world around me. I am blessed to have a voice. I am blessed to have an audience that listens to it, that believes everything I say. I am blessed to have a reason to speak. I am blessed to have family that understand. -

Janet Jackson's Rhythm Nation 1814

“Janet Jackson’s Rhythm Nation 1814”—Janet Jackson (1989) Added to the National Registry: 2020 Essay by Ayanna Dozier (guest post)* Janet Jackson Revolution Televised: “Janet Jackson’s Rhythm Nation” “Janet Jackson’s Rhythm Nation 1814” is a significant piece of Black feminist cultural production that pioneered new modes of using popular music to convey socio-cultural commentary to a larger mainstream audience. Conceptual in form, the album’s impact on youth culture is made possible by Jackson’s attentiveness to the televisual as seen in the album’s music videos and its incorporation of television culture in its sonic arrangement. Whereas Jackson’s contemporaries like Madonna, Prince, and even her brother Michael, adapted to television from radio early in their career, Jackson was one of the first true simultaneous audio/visual artists of the 1980s. What emerges from this practice is an album that without having seen its accompanying videos feels visual and cues images to the imagination upon each listen. “Rhythm Nation 1814” responds to what media historian John B. Thompson writes as the verisimilitude of mediated historicity. Mediated historicity defines the growing access we have to media images of the past that rather than represent history or an event we did not live through they simply 1 become history.0F “Rhythm Nation” materializes this strenuous period in which our lives, communication, and perception of time and space become mediated through the televisual and rarely exist outside of it. During an era where “I want my MTV” was feverishly chanted by teenagers across the country, “Rhythm Nation 1814” is a time capsule of how television began to permeate our quotidian experiences in an irrevocable way. -

Janet Jackson Celebrates 'Control'!

June 15, 2006 Janet Jackson Celebrates ‘Control’! When JANET JACKSON appeared on Us Weekly’s recent magazine cover in a skimpy bikini, the June 5th issue flew off the shelves, making it the best- selling cover of the year! It even clobbered the sales of previous editions with ANGELINA JOLIE, and NICK LACHEY and JESSICA SIMPSON, on the cover. Last night, Janet celebrated the issue’s success along with the 20th anniversary of her first blockbuster album, Control, which has inspired an all-new record, called 20 Years Old. Her first single with rapper NELLY, “Call on Me,” drops on Monday. “The inspiration came from music that inspired me 20 years ago and taking myself back to that time,” Janet tells our LARA SPENCER. “I hope you guys like it!” Janet may have just turned 40, but in her white jacket and tank top she still looks 20. She says she was amazed by the cover photo of herself, especially since she says she hates working out! “I said, ‘Goodness, that’s definitely a big difference!” Janet says, adding,”lf I can do it, they can. You have to have a wonderful trainer and someone who will drag you out of bed when you need it. TONY MARTINEZ has definitely dragged me out of bed and I\’e asked him to! I get very bored. One day it will be about tennis, the next day we’d hit balls at the batting cages. [It’s about] getting my heart rate up, keeping it going.” It’s also about nutrition. Enter Fresh Dining -- a popular L.A. -

The Totally 80S Karaoke Song List! Alpha by Artist

The Totally 80s Karaoke Song List! Alpha by Artist Disc # Artist Song J 89 10000 Maniacs Like The Weather D 229 38Special Hold On Loosely H 229 A Ha Take On Me H 645 Abba Super Trouper A 520 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long D 198 AC/DC Back In Black D 188 AC/DC Hells Bells H 38 Adam Ant Goody Two Shoes F2 1 Aerosmith Dude Looks Like a Lady F2 2 Aerosmith Love in an Elevator D 967 Aerosmith Walk This Way H 315 Air Supply All Out Of Love H 1124 Air Supply Lost In Love A 41 Alabama Mountain Music G 744 Alan Jackson Here In The Real World A 130 AlannahMyles Black Velvet D 118 Alice Cooper Generation Landslide D 777 AlJarreau After All H 1024 Amy Grant El Shaddai H 1000 Amy Grant / Peter Cetera Next Time I Fall H 1165 Anita Baker Caught Up In The Rapture A 652 AnitaBaker Sweet Love G 1076 Atlantic Star Always H 251 Atlantic Star Secret Lovers B 126 Atlantic Starr Always H 1200 Atlantic Starr Masterpiece H 245 B. Segar / Silver Bul. Against The Wind D 1179 B52's Love Shack H 185 B-52's Roam H 254 Bad English When I See You Smile A 337 Bananarama Venus H 187 Bananarama Cruel Summer D 902 Bangles Eternal Flame D 1201 Bangles Manic Monday A 339 Bangles Walk Like An Egyptian D 1139 Barbra Streisand Memory D 1106 Barbra Streisand People J 76 Barbra Streisand/Barry GibbGuilty H 282 Berlin Take My Breath Away G 714 Bertie Higgins Just Another Day In Paradise D 1067 Bette Midler Wind Beneath My Wings, The A 561 Billy Idol Cradle Of Love E2 15 Billy Idol Rebel Yell H 1228 Billy Idol White Wedding A 336 Billy Joel It's Still Rock And Roll To Me A 321 -

Janet Marie Sullivan

They are the best accomplishments of my life – my three children- Kathryn, Kim, and Chris. Janet Marie Sullivan A great deal of time and a great deal of love went into two other pursuits of Janet’s life. Her care and love of patients in the nursing profession lasted for over thirty years. Her interest in everything historical brought her to historical preservation. Janet Marie Sullivan Interviewer: Today is October 6, 2008. My name is Suzanne Willis and we are interviewing Janet Sullivan who has just told me that her full name is Janet Marie Sullivan. One of the reasons we wanted to interview you, besides your being an interesting person, is because this project by HFFI was established to record various community leaders’ involvement with historic preservation. Since you are one who does a great deal, we want to do an in-depth interview. Janet Sullivan: That would be great. Interviewer: Let us start with you first. What date were you born? Janet Sullivan: The date was December 30, 1942 during the war. My father (Woodrow Wilson Jones) had gone into the service and he was not here for my birth. He served on a mine sweeper, the USS Smythe, and he made about four crossings on the Atlantic side and then was sent to the Pacific. He went into Borneo and then into Japan. Interviewer: He wouldn’t have seen you until when? Janet Sullivan: I don’t know when he saw me. There are pictures of him holding me, so he must have come home between the Atlantic and Pacific crossings and I must have been a year old at that time. -

Neon Velvet Song List

Artist Song Genre Decade 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Rock 80s 311 Amber Pop 90s 311 Love Song Pop 90s ACDC You Shook Me All Night Long* Rock 80s A-ha Take On Me Pop 80s Atlas Genius Atlas Genius Rock 2010s Audioslave Like A Stone Rock 2000s B52s Love Shack Pop 80s Bee Gees You Should Be Dancing Pop 70s Big Data Dangerous Rock 2010s Billy Idol Dancin' With Myself Rock 80s Billy Idol Mony Mony Rock 80s Billy Idol Rebel Yell Rock 80s Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling* Pop 2000s Black Keys Fever Rock 2010s Bloc Party Banquet Rock 2000s Bruce Springsteen Dancing in the Dark Pop 80s Bruno Mars Treasure R&B 2010s Bruno Mars Uptown Funk R&B 2010s Bryan Adams Summer of 69 Rock 80s Capitol Cities Safe and Sound Pop 2010s Chris Isaak Wicked Game* Pop 80s Clash Rock The Casbah Rock 80s Coldplay Adventure of a Lifetime Pop 2010s Coldplay A Sky Full Of Stars* Pop 2010s Culture Club Do You Really Want To Hurt Me Pop 80s Cure Just Like Heaven Pop 80s Cure lovesong Pop 80s Cyndi Lauper Time After Time Pop 80s Daft Punk Get Lucky R&B 2000s Darius Rucker Wagon Wheel* Country 2000s David Bowie Fashion Rock 80s David Bowie Let's Dance Pop 80s Dead or Alive You Spin Me Round (Like a Record) Pop 80s Dean Martin Sway* Oldies 50s Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me Rock 80s Depeche Mode Enjoy the Silence Pop 80s Depeche Mode Just Can't Get Enough Pop 80s Devo Girl U Want Rock 80s Devo Whip It Pop 80s DNCE Cake By The Ocean Pop 2010s Drake Hotline Bling* R&B 2010s Duran Duran Hungry Like The Wolf Pop 80s Duran Duran Rio Pop 80s Ed Sheeran Shape of You Pop 2010s Edwyn Collins