Soda Bottle Volcano

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hawaii Volcanoes National Park Geologic Resources Inventory Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2009/163 THIS PAGE: Geologists have lloongng been monimonittoorriing the volcanoes of Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park. Here lalava cascades durduriingng the 1969-1971 Mauna Ulu eruption of Kīlauea VolVolcano. NotNotee the Mauna Ulu fountountaiain in the background. U.S. Geologiogicalcal SurSurvveyey PhotPhotoo by J. B. Judd (12/30/1969). ON THE COVER: ContContiinuouslnuouslyy eruptuptiingng since 1983, Kīllaueaauea Volcano contcontiinues to shapshapee Hawai‘Hawai‘i VoVollccanoes NatiNationalonal ParkPark.. Photo courtesy Lisa Venture/UniversiUniversitty of Cincinnati. Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2009/163 Geologic Resources Division Natural Resource Program Center P.O. Box 25287 Denver, Colorado 80225 December 2009 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Denver, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Program Center publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate high-priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. The series targets a general, diverse audience, and may contain NPS policy considerations or address sensitive issues of management applicability. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

Poroelastic Responses of Confined Aquifers to Subsurface Strain And

Solid Earth, 6, 1207–1229, 2015 www.solid-earth.net/6/1207/2015/ doi:10.5194/se-6-1207-2015 © Author(s) 2015. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Poroelastic responses of confined aquifers to subsurface strain and their use for volcano monitoring K. Strehlow, J. H. Gottsmann, and A. C. Rust School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Wills Memorial Building, Bristol BS8 1RJ, UK Correspondence to: K. Strehlow ([email protected]) Received: 11 May 2015 – Published in Solid Earth Discuss.: 9 June 2015 Revised: 18 September 2015 – Accepted: 21 October 2015 – Published: 10 November 2015 Abstract. Well water level changes associated with mag- aquifer and are commonly neglected in analytical models. matic unrest can be interpreted as a result of pore pressure These findings highlight the need for numerical models for changes in the aquifer due to crustal deformation, and so the interpretation of observed well level signals. However, could provide constraints on the subsurface processes caus- simulated water table changes do indeed mirror volumetric ing this strain. We use finite element analysis to demonstrate strain, and wells are therefore a valuable addition to monitor- the response of aquifers to volumetric strain induced by pres- ing systems that could provide important insights into pre- surized magma reservoirs. Two different aquifers are invoked eruptive dynamics. – an unconsolidated pyroclastic deposit and a vesicular lava flow – and embedded in an impermeable crust, overlying a magma chamber. The time-dependent, fully coupled models simulate crustal deformation accompanying chamber pres- 1 Introduction surization and the resulting hydraulic head changes as well as flow through the porous aquifer, i.e. -

Depth of Magma Chamber Determined by Experimental Petrologic Methods

DEPTH OF MAGMA CHAMBER DETERMINED BY EXPERIMENTAL PETROLOGIC METHODS Akihiko Tomiya Geological Survey of Japan, 1-1-3, Higashi, Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan Keywords: magma chamber, experimental petrology, Usu magma and, therefore, the composition of the residual melt, volcano, deep-seated geothermal resource that is, the evolved magma. ABSTRACT Thermodynamic conditions of a magma chamber can be estimated using petrographic information (e.g., compositions Depth of magma chamber (or young intrusive body) is one of and modal fractions of phenocrysts and groundmass) from a the most important parameters that determine the thermal representative rock erupted from the chamber. In order to structure and the circulation pattern of fluid around a estimate the pressure of magma chamber, the following geothermal area. The depth is also important when we methods are generally used; (1) geobarometer, (2) water recognize the magma chamber as a deep-seated geothermal content, and (3) melting experiment. One of the examples of resource itself. Here, we introduce an experimental petrologic the first method is an amphibole geobarometer (e.g., method for determining the depth of magma chamber. There Hammarstrom and Zen, 1986) where pressure is estimated are several methods in order to determine the depth (pressure) from the aluminum content of the amphibole crystallized from of a magma chamber. Among them, a melting experiment for the magma. This method, however, is difficult to apply to the rock erupted from the magma chamber is the most reliable natural magma because the geobarometer should be applied method. The method consists of the following procedure: (1) only when the mineral assemblage of the magma is the same as Select a sample (volcanic rock) which is representative of that of experimental products for which the geobarometer was magma in the chamber; (2) Give a petrographic description of calibrated. -

150 Geologic Facts About California

California Geological Survey - 150th Anniversary 150 Geologic Facts about California California’s geology is varied and complex. The high mountains and broad valleys we see today were created over long periods of time by geologic processes such as fault movement, volcanism, sea level change, erosion and sedimentation. Below are 150 facts about the geology of California and the California Geological Survey (CGS). General Geology and Landforms 1 California has more than 800 different geologic units that provide a variety of rock types, mineral resources, geologic structures and spectacular scenery. 2 Both the highest and lowest elevations in the 48 contiguous states are in California, only 80 miles apart. The tallest mountain peak is Mt. Whitney at 14,496 feet; the lowest elevation in California and North America is in Death Valley at 282 feet below sea level. 3 California’s state mineral is gold. The Gold Rush of 1849 caused an influx of settlers and led to California becoming the 31st state in 1850. 4 California’s state rock is serpentine. It is apple-green to black in color and is often mottled with light and dark colors, similar to a snake. It is a metamorphic rock typically derived from iron- and magnesium-rich igneous rocks from the Earth’s mantle (the layer below the Earth’s crust). It is sometimes associated with fault zones and often has a greasy or silky luster and a soapy feel. 5 California’s state fossil is the saber-toothed cat. In California, the most abundant fossils of the saber-toothed cat are found at the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles. -

Discovery of a Hydrothermal Fissure in the Danakil Depression

EPSC Abstracts Vol. 12, EPSC2018-381-1, 2018 European Planetary Science Congress 2018 EEuropeaPn PlanetarSy Science CCongress c Author(s) 2018 Discovery of a hydrothermal fissure in the Danakil depression Daniel Mège (1), Ernst Hauber (2), Mieke De Craen (3), Hugo Moors (3) and Christian Minet (2) (1) Space Research Centre, Polish Academy of Sciences, Poland ([email protected]), (2) DLR, Germany ([email protected], [email protected], (3) Belgian Nuclear Research Centre, Belgium ([email protected], [email protected]) Abstract Oily Lake and Gaet’Ale). It is manifested by (1) salt polygon geometry directly influenced by the underlying Volcanic rift zones are among the most emblematic fracture; (2) bubbling pools; (3) dead pools; (4) shallow analogue features on Earth and Mars [1-2], with expected sinkholes; (4) a variety of other micromorphologies differences mainly resulting from the different value of a related to free or pressurised upflow of gas and fluids; single parameter, gravity [3]. Beyond the understanding and (5) rare evidence of fumarolic activity. In this context, of the geology, rift zones provide appropriate the Yellow Lake appears as a possible salt karst feature hydrothermal environments for the development of [10] the location and growth of which is controlled by micro-organisms in extreme conditions which depend at relay zone deformation between the fissure segments. first order on endogenic processes, and weakly on the planetary climate conditions. The Europlanet 2018 3. Hydrothermal fluids Danakil field campaign enabled identifying a previously The physico-chemistry of fluids and minerals from two unreported 4.5 km long hydrothermal fissure on the Lake small pools located along the Yellow Lake Fissure, as Asale salt flats, the Erta Ale - Dallol segment of the well as the Yellow Lake, have been analysed (Table 1). -

Fs20193026.Pdf

Prepared in collaboration with U.S. Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Colorado Division of Reclamation Mining and Safety, Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, and Animas River Stakeholders Group Geological and Geophysical Data for a Three-Dimensional View— Inside the San Juan and Silverton Calderas, Southern Rocky Mountains Volcanic Field, Silverton, Colorado This study integrates geological and geophysical data important for developing a three-dimensional (3D) model of the San Juan-Silverton caldera complex. The project aims to • apply state-of-the-art geophysical data processing techniques to legacy data; • map subsurface lithologies, faults, vein structures, and surficial deposits that may be groundwater flow paths; • better understand geophysical response of mineral systems at depth; and • provide geological and geophysical frameworks that will inform mining reclamation decisions and mineral resource assessments. Introduction shallow properties important for understanding surface water and groundwater quality issues and will also improve knowl- The San Juan-Silverton caldera complex located near edge of deep geological structures that may have been conduits Silverton, Colorado, in the Southern Rocky Mountains volcanic for hydrothermal fluids that formed mineral deposits (fig. 1). field is an ideal natural laboratory for furthering the under- The study has general applications to mineral resource assess- standing of shallow-to-deep volcanic-related mineral systems. ments -

State of Stress During Onset and Evolution of Caldera Collapse

Originally published as: Holohan, E., Schöpfer, M. P. J., Walsh, J. J. (2015): Stress evolution during caldera collapse. - Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 421, p. 139-151. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2015.03.003 1 Stress evolution during caldera collapse 2 E.P. Holohan(1,2), M.P.J. Schöpfer(1,3), & J.J. Walsh(1) 3 (1) GFZ Potsdam, Section 2.1 – Physics of Earthquakes and Volcanoes, Telegrafenberg, Potsdam 14473, Germany. 4 (2) Fault Analysis Group, UCD School of Geological Sciences, Dublin 4, Ireland. 5 (3) Department for Geodynamics and Sedimentology, University of Vienna, Althanstrasse 14, Vienna, Austria. 6 Email: [email protected] 7 8 Abstract 9 The dynamics of caldera collapse are subject of long-running debate. Particular uncertainties 10 concern how stresses around a magma reservoir relate to fracturing as the reservoir roof collapses, 11 and how roof collapse in turn impacts upon the reservoir. We used two-dimensional Distinct 12 Element Method models to characterise the evolution of stress around a depleting sub-surface 13 magma body during gravity-driven collapse of its roof. These models illustrate how principal stress 14 directions rotate during progressive deformation so that roof fracturing transitions from initial 15 reverse faulting to later normal faulting. They also reveal four end-member stress paths to fracture, 16 each corresponding to a particular location within the roof. Analysis of these paths indicates that 17 fractures associated with ultimate roof failure initiate in compression (i.e. as shear fractures). We 18 also report on how mechanical and geometric conditions in the roof affect pre-failure unloading and 19 post-failure reloading of the reservoir. -

Warren, J. K. Volatile Evaporite Interactions with Magma, Part 2 of 3

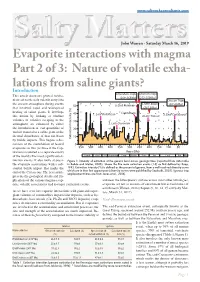

www.saltworkconsultants.com Salty MattersJohn Warren - Saturday March 16, 2019 Evaporite interactions with magma Part 2 of 3: Nature of volatile exha- lations from saline giants? Introduction Emeishan Traps Siberian Traps This article discusses general mecha- (269-265Ma) (253-250Ma) nisms of earth-scale volatile entry into Deccan Traps CAMP, Brazil the ancient atmosphere during events 50 3. End-Permian (67-65Ma) that involved rapid and widespread (201.5Ma) heating of saline giants. It develops 40 1. Late Ordovican Capitanian 5. End-Cretaceous this notion by looking at whether 4.Late Triassic volumes of volatiles escaping to the 30 atmosphere are enhanced by either 2. Late Devonian the introduction of vast quantities of 20 molten material to a saline giant or the thermal disturbance of that salt basin 10 Extinction Intensity (%) by bolide impacts. This begins a dis- cussion of the contribution of heated 0 evaporites in two (or three if the Cap- 550 500 450 400 350 300 250 200 150 100 50 titanian is counted as a separate event) Years (Ma) of the world's five most significant ex- Camb. Ord. Sil. Devonian Carb. Perm. Trias. Jur. Cret. Pal. Neo tinction events. It also looks at possi- Figure 1. Intensity of extinction at the genera level across geologic time (replotted from data table ble evaporite associations with a sub- in Rohde and Muller, 2005). Shows the five main extinction events (1-5) as first defined by Raup, stantial bolide impact that marks the 1982. Extinction intensity (%) is defined as the precent of genera, from a well-resolved diversity curve which are in their last appearance (diversity curves were published by Sepkoski, 2002). -

Future Volcanism at Yellowstone Caldera: Insights from Geochemistry of Young Volcanic Units and Monitoring of Volcanic Unrest

2012 Annual Meeting & Exposition Issue! SEPTEMBER 2012 | VOL. 22, NO. 9 A PUBLICATION OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA® Future volcanism at Yellowstone caldera: Insights from geochemistry of young volcanic units and monitoring of volcanic unrest Inside: Preliminary Announcement and Call for Papers: 2013 GSA Northeastern Section Meeting, p. 38 Preliminary Announcement and Call for Papers: 2013 GSA Southeastern Section Meeting, p. 41 VOLUME 22, NUMBER 9 | 2012 SEPTEMBER SCIENCE ARTICLE GSA TODAY (ISSN 1052-5173 USPS 0456-530) prints news and information for more than 25,000 GSA member read- ers and subscribing libraries, with 11 monthly issues (April/ May is a combined issue). GSA TODAY is published by The Geological Society of America® Inc. (GSA) with offices at 3300 Penrose Place, Boulder, Colorado, USA, and a mail- ing address of P.O. Box 9140, Boulder, CO 80301-9140, USA. 4 Future volcanism at Yellowstone GSA provides this and other forums for the presentation of diverse opinions and positions by scientists worldwide, caldera: Insights from geochemistry regardless of race, citizenship, gender, sexual orientation, of young volcanic units and religion, or political viewpoint. Opinions presented in this monitoring of volcanic unrest publication do not reflect official positions of the Society. Guillaume Girard and John Stix © 2012 The Geological Society of America Inc. All rights reserved. Copyright not claimed on content prepared Cover: View looking west into the Midway geyser wholly by U.S. government employees within the scope of basin of Yellowstone caldera (foreground) and the West their employment. Individual scientists are hereby granted permission, without fees or request to GSA, to use a single Yellowstone rhyolite lava flow (background). -

United States Department of the Interior Geological Survey Proceedings of Workshop Xix Active Tectonic and Magmatic Processes Be

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROCEEDINGS OF WORKSHOP XIX ACTIVE TECTONIC AND MAGMATIC PROCESSES BENEATH LONG VALLEY CALDERA, EASTERN CALIFORNIA VOLUME I 24 - 27 January 1984 Sponsored by U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY VOLCANO HAZARDS PROGRAM Editors and Convenors David P. Hill U.S. Geological Survey Menlo Park, California 94025 Roy A. Bailey U.S. Geological Survey Menlo Park, California 94025 Allan S. Ryall University of Nevada Reno, Nevada 89557-0018 OPEN-FILE REPORT 84-939 Compiled by Muriel Jacobson This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature. Any use of trade names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the USGS. MENLO PARK, CALIFORNIA 1984 CONFERENCES TO DATE Conference I Abnormal Animal Behavior Prior to Earthquakes, I Not Open-Filed Conference II Experimental Studies of Rock Friction with Application to Earthquake Prediction Not Open-Filed Conference III Fault Mechanics and Its Relation to Earthquake Prediction Open-File No. 78-380 Conference IV Use of Volunteers in the Earthquake Hazards Reduction Program Open-File No. 78-336 Conference V Communicating Earthquake Hazard Reduction Information Open-File No. 78-933 Conference VI Methodology for Identifying Seismic Gaps and Soon-to-Break Gaps Open-File No. 78-943 Conference VII Stress and Strain Measurements Related to Earthquake Prediction Open-File No. 79-370 Conference VIII Analysis of Actual Fault Zones in Bedrock Open-File No. 79-1239 Conference IX Magnitude of Deviatoric Stresses in the Earth's Crust and Upper Mantle Open-File No. -

A Geologic Study of the Capulin Volcano National Monument and Surrounding Areas, Union and Colfax Counties, New Mexico

A Geologic Study of the Capulin Volcano National Monument and surrounding areas, Union and Colfax Counties, New Mexico by William O. Sayre and Michael H. Ort New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources, New Mexico Tech Socorro, New Mexico 87801 Open-file Report 541 August, 2011 A geologic study of Capulin Volcano National Monument and surrounding areas Final Report Cooperative Agreement CA7029-2-0017 December 4, 1999 Submitted to: Capulin Volcano National Monument P. O. Box 80 Capulin, New Mexico 88414 Submitted by: William O. Sayre, Ph.D., P.G. College of Santa Fe 1600 St. Michael’s Drive Santa Fe, New Mexico 87505-7634 and Michael H. Ort, Ph.D. Department of Geology PO Box 4099 Northern Arizona University Flagstaff, Arizona 86011 Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ 2 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 2 Body of Report .............................................................................................................. 17 Discussion and Conclusions ......................................................................................... 22 Recommendations for Future Work .............................................................................. 64 References .................................................................................................................... 65 Appendices……………………………………………………………………………………. -

Occurrence and Absence of Lava Tube Caves with Some Other Volcanic Cavities; a Consideration of Hu- Man Habitation Sites on Mars

43rd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2012) 1613.pdf Occurrence and Absence Of Lava Tube Caves With Some Other Volcanic Cavities; a Consideration of Hu- man Habitation Sites on Mars. W.R. Halliday (1,2), G. Favre (1,3), A. Stefansson (4), P. Whitfield (5) and N. Banks (6). 1) Commission on Volcanic Caves of the International Union of Speleology, 2) Hawaii Speleological Survey of the National Speleological Society, 3) Swiss Speleological Society, 4) Thrihnukar e.h.f., 5) British Colum- bia Speleological Federation and 6) US Geological Survey (retired). [email protected], 6530 Cornwall Court, Nashville, TN 37205 USA In 1839, American missionaries in the Kingdom of ern pit crater was seen to be much like the western ex- Hawaii showed professor-to-be James Dana some lo- ample, plus a small alcove at its base. Its walls contain cally celebrated pit craters on the east rift zone of Ki- three rudimentary lava tubes much like those in the lauea Volcano (1). Dana recognized them as rem- western pit crater, but it does not connect to any lava nants of circular pools of molten lava with subsequent tube feeding system, and as Favre remarked (5), it does withdrawal of their lava column. Other pit craters were not “open out into a vast underground system”. De- found around the world, perhaps most notably on the spite published statements to the contrary, no terrestrial rift zones of Hawaii’s Hualalai Volcano where they are pit crater has been documented as a skylight of any so isolated that few have been investigated.