24 International Congress of CIRIEC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Community Structure of Insects on the Stored Traditional Chinese Medicinal (TCM) Materials in Shandong Province, China

Proceedmqs of the 7th Internationol WOI kuu) Conference on Stored-product Protectum - Volume 1 The community structure of insects on the stored traditional Chinese medicinal (TCM) materials in Shandong Province, China Liu Guilm", Ye Baohua", LI Zhaohui", Zheng Fangqiang", Liang Xiaowerr , Liu Yongh2 and LI Changzheng! Abstract One hundred species of insects on the stored Traditional Methods Chinese Medicinal (TCM) matenals belonging to 10 orders and 43 farmhes were Identified m 20 regions of Shandong Survey methods Provmce , China The commumty structure of msects on the Survey reqions stored TCM matenals m different regions was analysed, Twenty representitrve survey regions involved are showing that the mam group m the commurutres was Yanzhou, Jmmg , Zhangdian , Omgdao , Dezhou, Yucheng, coleopterous msects (72 species, makmg up 72% of the LaIWU, Rizhao, Bmzhou, Weifang , Zhucheng, LmYI, total number of species) and Then was Iepidopterous insects Liaocheng, Changqmg, Zaozhuang, Laiyang, Dongymg, (9 species, accounting for 9 % of the total number of Iman, Heze and Taian The msect commumty structure of species) The number of coleopterous species m 20 regions Taian TCM matenal station was studied in detail in a ranges from -+ to 37, accountmg for 61 54 - 90 00% (80 72 tamporal sequence ± 7 67%) The dominant species m different regions Samplmg procedure were studied The results indicated that Sieqobucni Five quadrats were taken from each kmd of TCM paniceum (L) PlOOIO interpunciella (Hubner) and matenals One kilogram TCM matenal from each -

Decision Memorandum for the Preliminary Results of the Antidumping Duty Administrative Review: Certain Steel Nails from the People’S Republic of China; 2018-2019

A-570-909 Administrative Review POR: 8/1/2018 - 7/31/2019 Public Document E&C/V: BB December 14, 2020 MEMORANDUM TO: Joseph A. Laroski Jr. Deputy Assistant Secretary for Policy and Negotiations FROM: James Maeder Deputy Assistant Secretary for Antidumping and Countervailing Duty Operations SUBJECT: Decision Memorandum for the Preliminary Results of the Antidumping Duty Administrative Review: Certain Steel Nails from the People’s Republic of China; 2018-2019 I. SUMMARY The Department of Commerce (Commerce) is conducting an administrative review of the antidumping duty (AD) order on certain steel nails (nails) from the People’s Republic of China (China) for the period of review (POR) from August 1, 2018 through July 31, 2019. We initiated this administrative review with respect to 308 companies.1 We subsequently selected two of these companies as mandatory respondents, Shandong Oriental Cherry Hardware Group Co. Ltd. (Shandong Oriental) and Tianjin Zhonglian Metals Ware Co., Ltd. (Zhonglian). We preliminarily determine that Zhonglian made sales of subject merchandise at prices below normal value (NV). In addition, we preliminarily determine that nine companies, including Zhonglian, are eligible for a separate rate, 10 companies had no shipments, and 287 companies, including Shandong Oriental, are part of the China-wide entity. Finally, we are rescinding this review with respect to The Stanley Works (Langfang) Fastening Systems Co., Ltd. and Stanley Black & Decker Inc. (collectively, Stanley). 1 We note that we inadvertently initiated a review of one company twice, once as “Tianjin Jinghai County Hongli Industry & Business Co., Ltd.“ and again as “Tianjin Jinghai County Hongli Industry and Business Co., Ltd.” We are treating these companies as the same entity for purposes of this segment of the proceeding. -

ATTACHMENT 1 Barcode:3800584-02 C-570-107 INV - Investigation

ATTACHMENT 1 Barcode:3800584-02 C-570-107 INV - Investigation - Chinese Producers of Wooden Cabinets and Vanities Company Name Company Information Company Name: A Shipping A Shipping Street Address: Room 1102, No. 288 Building No 4., Wuhua Road, Hongkou City: Shanghai Company Name: AA Cabinetry AA Cabinetry Street Address: Fanzhong Road Minzhong Town City: Zhongshan Company Name: Achiever Import and Export Co., Ltd. Street Address: No. 103 Taihe Road Gaoming Achiever Import And Export Co., City: Foshan Ltd. Country: PRC Phone: 0757-88828138 Company Name: Adornus Cabinetry Street Address: No.1 Man Xing Road Adornus Cabinetry City: Manshan Town, Lingang District Country: PRC Company Name: Aershin Cabinet Street Address: No.88 Xingyuan Avenue City: Rugao Aershin Cabinet Province/State: Jiangsu Country: PRC Phone: 13801858741 Website: http://www.aershin.com/i14470-m28456.htmIS Company Name: Air Sea Transport Street Address: 10F No. 71, Sung Chiang Road Air Sea Transport City: Taipei Country: Taiwan Company Name: All Ways Forwarding (PRe) Co., Ltd. Street Address: No. 268 South Zhongshan Rd. All Ways Forwarding (China) Co., City: Huangpu Ltd. Zip Code: 200010 Country: PRC Company Name: All Ways Logistics International (Asia Pacific) LLC. Street Address: Room 1106, No. 969 South, Zhongshan Road All Ways Logisitcs Asia City: Shanghai Country: PRC Company Name: Allan Street Address: No.188, Fengtai Road City: Hefei Allan Province/State: Anhui Zip Code: 23041 Country: PRC Company Name: Alliance Asia Co Lim Street Address: 2176 Rm100710 F Ho King Ctr No 2 6 Fa Yuen Street Alliance Asia Co Li City: Mongkok Country: PRC Company Name: ALMI Shipping and Logistics Street Address: Room 601 No. -

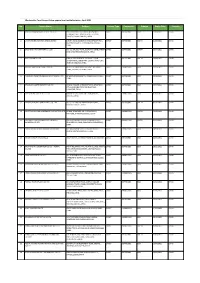

Apparel & Textile Factory List

Woolworths Food Group-Active apparel and textile factories- April 2021 No. Factory Name Address Factory Type Commodity Scheme Expiry Date Country 1 JIANGSU HONGMOFANG TEXTILE CO., LTD EAST CIFU ROAD, EAST RUISHENG AVENUE,, DIRECT SOFTGOODS BSCI 23/04/2021 CHINA ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ZONE, SHUYANG COUNTY,,SUQIAN,JIANGSU,,CHINA 2 LIANYUNGANG ZHAOWEN SHOES LIMITED 2 BEIHAI ROAD,ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AREA, DIRECT SOFTGOODS SMETA 11/05/2021 CHINA GUANNAN COUNTY,,LIANYUNGANG,JIANGSU,, CHINA 3 ZHUCHENG YIXIN GARMENT CO., LTD NO. 321 SHUNDU ROAD,,ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT DIRECT SOFTGOODS SMETA 13/07/2021 CHINA ZONE,,ZHUCHENG,SHANDONG,,CHINA 4 HRX FASHION CO LTD 1000 METERS SOUTH OF GUOCANG TOWN DIRECT SOFTGOODS SMETA 25/08/2021 CHINA GOVERNMENT,,WENSHANG COUNTY, JINING CITY, JINING,SHANDONG,,CHINA 5 PUJIANG KINGSHOW CARPET CO LTD NO.75-1 ZHEN PU ROAD, PU JIANG, ZHE JIANG, DIRECT HARDGOODS BSCI 24/12/2021 CHINA CHINA,,PUJIANG,ZHEJIANG,,CHINA 6 YANGZHOU TENGYI SHOES MANUFACTURE CO., LTD. 13 WEST HONGCHENG RD,,,FANGXIANG,JIANGSU,, DIRECT SOFTGOODS BSCI 22/10/2021 CHINA CHINA 7 ZHAOYUAN CASTTE GARMENT CO LTD PANJIAJI VILLAGE, LINGLONG TOWN,,ZHAOYUAN DIRECT SOFTGOODS BSCI 06/07/2021 CHINA CITY, SHANDONG PROVINCE,ZHAOYUAN, SHANDONG,,CHINA 8 RUGAO HONGTAI TEXTILE CO LTD XINJIAN VILLAGE, JIANGAN TOWN,,RUGAO, DIRECT HARDGOODS BSCI 07/12/2021 CHINA JIANGSU,,CHINA 9 NANJING BIAOMEI HOMETEXTILES CO.,LTD NO.13 ERST WUCHU ROAD,HENGXI TOWN,,, DIRECT SOFTGOODS SMETA 04/11/2021 CHINA NANJING,JIANGSU,,CHINA 10 NANTONG YAOXING HOUSEWARE PRODUCTS CO.,LTD NO.999, TONGFUBEI RD., CHONGCHUAN, DIRECT HARDGOODS SMETA 24/09/2021 CHINA NANTONG,,NANTONG,JIANGSU,,CHINA 11 CHAOZHOU CHAOAN ZHENGYUN CERAMICS QIAO HU VILLAGE, CHAOAN, CHAOZHOU CITY, DIRECT HARDGOODS SMETA 19/05/2021 CHINA INDUSTRIAL CO LTD GUANGDONG, CHINA,,CHAOZHOU,GUANGDONG,, CHINA 12 YANTAI PACIFIC HOME FASHION FUSHAN MILL NO. -

Cereal Series/Protein Series Jiangxi Cowin Food Co., Ltd. Huangjindui

产品总称 委托方名称(英) 申请地址(英) Huangjindui Industrial Park, Shanggao County, Yichun City, Jiangxi Province, Cereal Series/Protein Series Jiangxi Cowin Food Co., Ltd. China Folic acid/D-calcium Pantothenate/Thiamine Mononitrate/Thiamine East of Huangdian Village (West of Tongxingfengan), Kenli Town, Kenli County, Hydrochloride/Riboflavin/Beta Alanine/Pyridoxine Xinfa Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Dongying City, Shandong Province, 257500, China Hydrochloride/Sucralose/Dexpanthenol LMZ Herbal Toothpaste Liuzhou LMZ Co.,Ltd. No.282 Donghuan Road,Liuzhou City,Guangxi,China Flavor/Seasoning Hubei Handyware Food Biotech Co.,Ltd. 6 Dongdi Road, Xiantao City, Hubei Province, China SODIUM CARBOXYMETHYL CELLULOSE(CMC) ANQIU EAGLE CELLULOSE CO., LTD Xinbingmaying Village, Linghe Town, Anqiu City, Weifang City, Shandong Province No. 569, Yingerle Road, Economic Development Zone, Qingyun County, Dezhou, biscuit Shandong Yingerle Hwa Tai Food Industry Co., Ltd Shandong, China (Mainland) Maltose, Malt Extract, Dry Malt Extract, Barley Extract Guangzhou Heliyuan Foodstuff Co.,LTD Mache Village, Shitan Town, Zengcheng, Guangzhou,Guangdong,China No.3, Xinxing Road, Wuqing Development Area, Tianjin Hi-tech Industrial Park, Non-Dairy Whip Topping\PREMIX Rich Bakery Products(Tianjin)Co.,Ltd. Tianjin, China. Edible oils and fats / Filling of foods/Milk Beverages TIANJIN YOSHIYOSHI FOOD CO., LTD. No. 52 Bohai Road, TEDA, Tianjin, China Solid beverage/Milk tea mate(Non dairy creamer)/Flavored 2nd phase of Diqiuhuanpo, Economic Development Zone, Deqing County, Huzhou Zhejiang Qiyiniao Biological Technology Co., Ltd. concentrated beverage/ Fruit jam/Bubble jam City, Zhejiang Province, P.R. China Solid beverage/Flavored concentrated beverage/Concentrated juice/ Hangzhou Jiahe Food Co.,Ltd No.5 Yaojia Road Gouzhuang Liangzhu Street Yuhang District Hangzhou Fruit Jam Production of Hydrolyzed Vegetable Protein Powder/Caramel Color/Red Fermented Rice Powder/Monascus Red Color/Monascus Yellow Shandong Zhonghui Biotechnology Co., Ltd. -

20200316 Factory List.Xlsx

Country Factory Name Address BANGLADESH AMAN WINTER WEARS LTD. SINGAIR ROAD, HEMAYETPUR, SAVAR, DHAKA.,0,DHAKA,0,BANGLADESH BANGLADESH KDS GARMENTS IND. LTD. 255, NASIRABAD I/A, BAIZID BOSTAMI ROAD,,,CHITTAGONG-4211,,BANGLADESH BANGLADESH DENITEX LIMITED 9/1,KORNOPARA, SAVAR, DHAKA-1340,,DHAKA,,BANGLADESH JAMIRDIA, DUBALIAPARA, VALUKA, MYMENSHINGH BANGLADESH PIONEER KNITWEARS (BD) LTD 2240,,MYMENSHINGH,DHAKA,BANGLADESH PLOT # 49-52, SECTOR # 08 , CEPZ, CHITTAGONG, BANGLADESH HKD INTERNATIONAL (CEPZ) LTD BANGLADESH,,CHITTAGONG,,BANGLADESH BANGLADESH FLAXEN DRESS MAKER LTD MEGHDUBI, WARD: 40, GAZIPUR CITY CORP,,,GAZIPUR,,BANGLADESH BANGLADESH NETWORK CLOTHING LTD 228/3,SHAHID RAWSHAN SARAK, CHANDANA,,,GAZIPUR,DHAKA,BANGLADESH 521/1 GACHA ROAD, BOROBARI,GAZIPUR CITY BANGLADESH ABA FASHIONS LTD CORPORATION,,GAZIPUR,DHAKA,BANGLADESH VILLAGE- AMTOIL, P.O. HAT AMTOIL, P.S. SREEPUR, DISTRICT- BANGLADESH SAN APPARELS LTD MAGURA,,JESSORE,,BANGLADESH BANGLADESH TASNIAH FABRICS LTD KASHIMPUR NAYAPARA, GAZIPUR SADAR,,GAZIPUR,,BANGLADESH BANGLADESH AMAN KNITTINGS LTD KULASHUR, HEMAYETPUR,,SAVAR,DHAKA,BANGLADESH BANGLADESH CHERRY INTIMATE LTD PLOT # 105 01,DEPZ, ASHULIA, SAVAR,DHAKA,DHAKA,BANGLADESH COLOMESSHOR, POST OFFICE-NATIONAL UNIVERSITY, GAZIPUR BANGLADESH ARRIVAL FASHION LTD SADAR,,,GAZIPUR,DHAKA,BANGLADESH VILLAGE-JOYPURA, UNION-SHOMBAG,,UPAZILA-DHAMRAI, BANGLADESH NAFA APPARELS LTD DISTRICT,DHAKA,,BANGLADESH BANGLADESH VINTAGE DENIM APPARELS LIMITED BOHERARCHALA , SREEPUR,,,GAZIPUR,,BANGLADESH BANGLADESH KDS IDR LTD CDA PLOT NO: 15(P),16,MOHORA -

Igcp 679 2Nd Circular English

THE FIRST INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM OF THE INTERNATIONAL GEOSCIENCE PROGRAMME PROJECT 679 October 11–17, 2019, Qingdao, Shandong, China Second Circular “Linkage of Cretaceous solid earth dynamics, greenhouse climate, and response of ecosystems on land and in the oceans in Asia” Cretaceous Earth Dynamics and Climate in Asia INVITATION & AIMS We cordially invite you to participate in the 1st International Symposium of IGCP 679, which will be held during October 11–17, 2019 in Qingdao, China. The Cretaceous was the most recent, warmest period in the Phanerozoic Era, and characterized by more elevated atmospheric pCO2 levels and significantly higher global sea levels than today. The IGCP 679 project is aimed to explore the processes and mechanisms of the rapid change in climate and environment under greenhouse conditions during the Cretaceous, and the evolutionary responses of the biodiversity on land of the Asian continent and in the around oceans. The symposium scientific sessions will provide an opportunity for a close discussion of the latest research results on Asia-Pacific Cretaceous ecosystems and palaeoclimate. A pre-symposium field excursion will be organized to visit the Cretaceous terrestrial strata in Shandong Province, which contain abundant mega- and micro-fossils. In a three-day pre-symposium field excursion, we will visit some important sites to learn the latest research progress on the non-marine Cretaceous stratigraphy, and the yielding abundant various biotas. The organizing and scientific committees warmly welcome you in Qingdao, for the first IGCP 679 symposium, which is hosted by Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, and organized by Shandong Institute of Geological Survey together with School of Earth Science and Engineering, Shandong University of Science and Technology, and co-organized by Qingdao Geological Engineering Survey Institute. -

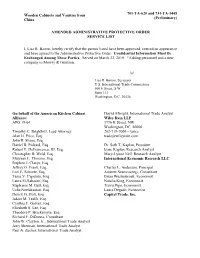

Administrative Protective Order Service List

701-TA-620 and 731-TA-1445 Wooden Cabinets and Vanities from China (Preliminary) AMENDED ADMINISTRATIVE PROTECTIVE ORDER SERVICE LIST I, Lisa R. Barton, hereby certify that the parties listed have been approved, entered an appearance and have agreed to the Administrative Protective Order. Confidential Information Must Be Exchanged Among These Parties. Served on March 22, 2019. *Adding personnel and a new company to Mowry & Grimson. /s/ Lisa R. Barton, Secretary U.S. International Trade Commission 500 E Street, S.W. Suite 112 Washington, D.C. 20436 On behalf of the American Kitchen Cabinet David Albright, International Trade Analyst Alliance: Wiley Rein LLP APO 19-64 1776 K Street, NW Washington, DC 20006 Timothy C. Brightbill, Lead Attorney 202-719-7000 – voice Alan H. Price, Esq. [email protected] John R. Shane, Esq. Daniel B. Pickard, Esq. Dr. Seth T, Kaplan, President Robert E. DeFrancesco, III, Esq. Isaac Kaplan, Research Analyst Christopher B. Weld, Esq. Mary-Lynne Neil, Research Analyst Maureen E. Thorson, Esq. International Economic Research LLC Stephen J. Claeys, Esq. Jeffrey O. Frank, Esq. Charles L. Anderson, Principal Lori E. Scheetz, Esq. Andrew Szamosszegi, Consultant Tessa V. Capeloto, Esq. Brian Westenbroek, Economist Laura El-Sabaawi, Esq. Natalia King, Economist Stephanie M. Bell, Esq. Travis Pipe, Economist Usha Neelakantan, Esq. Laura Degado, Economist Derick G. Holt, Esq. Capital Trade, Inc. Adam M. Teslik, Esq. Cynthia C. Galvez, Esq. Elizabeth S. Lee, Esq. Theodore P. Brackemyre, Esq. Richard F. DiDonna, Consultant John W. Clayton, Jr., International Trade Analyst Amy Sherman, International Trade Analyst Paul A. Zucker, International Trade Analyst Wooden Cabinets and Vanities from China 701-TA-620 and 731-TA-1445 (P) On behalf of Home Meridian International, Inc. -

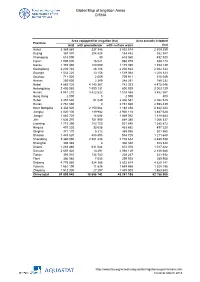

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA Area equipped for irrigation (ha) Area actually irrigated Province total with groundwater with surface water (ha) Anhui 3 369 860 337 346 3 032 514 2 309 259 Beijing 367 870 204 428 163 442 352 387 Chongqing 618 090 30 618 060 432 520 Fujian 1 005 000 16 021 988 979 938 174 Gansu 1 355 480 180 090 1 175 390 1 153 139 Guangdong 2 230 740 28 106 2 202 634 2 042 344 Guangxi 1 532 220 13 156 1 519 064 1 208 323 Guizhou 711 920 2 009 709 911 515 049 Hainan 250 600 2 349 248 251 189 232 Hebei 4 885 720 4 143 367 742 353 4 475 046 Heilongjiang 2 400 060 1 599 131 800 929 2 003 129 Henan 4 941 210 3 422 622 1 518 588 3 862 567 Hong Kong 2 000 0 2 000 800 Hubei 2 457 630 51 049 2 406 581 2 082 525 Hunan 2 761 660 0 2 761 660 2 598 439 Inner Mongolia 3 332 520 2 150 064 1 182 456 2 842 223 Jiangsu 4 020 100 119 982 3 900 118 3 487 628 Jiangxi 1 883 720 14 688 1 869 032 1 818 684 Jilin 1 636 370 751 990 884 380 1 066 337 Liaoning 1 715 390 783 750 931 640 1 385 872 Ningxia 497 220 33 538 463 682 497 220 Qinghai 371 170 5 212 365 958 301 560 Shaanxi 1 443 620 488 895 954 725 1 211 648 Shandong 5 360 090 2 581 448 2 778 642 4 485 538 Shanghai 308 340 0 308 340 308 340 Shanxi 1 283 460 611 084 672 376 1 017 422 Sichuan 2 607 420 13 291 2 594 129 2 140 680 Tianjin 393 010 134 743 258 267 321 932 Tibet 306 980 7 055 299 925 289 908 Xinjiang 4 776 980 924 366 3 852 614 4 629 141 Yunnan 1 561 190 11 635 1 549 555 1 328 186 Zhejiang 1 512 300 27 297 1 485 003 1 463 653 China total 61 899 940 18 658 742 43 241 198 52 -

Original Article the Effect of Mir-27A on the Proliferation, Apoptosis, and Chemosensitivity of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Cells by Targeting MCPH1

Int J Clin Exp Med 2020;13(12):9253-9267 www.ijcem.com /ISSN:1940-5901/IJCEM0120150 Original Article The effect of miR-27a on the proliferation, apoptosis, and chemosensitivity of non-small-cell lung cancer cells by targeting MCPH1 Yuxia Wu1*, Rui Zhang2*, Xiucheng Wang3, Mao Mao4, Penglong Li5 1Department of Respiratory Medicine, Heze Municipal Hospital, Heze, Shandong Province, China; 2Department of Thoracic Surgery, Dezhou Second People’s Hospital, Dezhou, Shandong Province, China; 3Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Zhucheng People’s Hospital, Zhucheng, Shandong Province, China; 4Department of Oncology, Zibo City Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital, Zibo, Shandong Province, China; 5Department of Oncology, Laiyang Central Hospital, Yantai, Shandong Province, China. *Equal contributors and co-first authors. Received August 12, 2020; Accepted September 16, 2020; Epub December 15, 2020; Published December 30, 2020 Abstract: Objective: We aimed to investigate the effect of miR-27a on the proliferation, apoptosis, and chemo- sensitivity of non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells by targeting microcephalin 1 (MCPH1). Methods: The target- ing relationship between miR-27a and MCPH1 was first verified using a dual-luciferase reporter assay. The cell line A549 was chosen for the experiments as it has a higher miR-27a expression level than the other three NSCLC cell lines, H1355, H460, and H520. The proliferation ability of the NSCLC cells and the IC50 values of doxorubicin and cisplatin for NSCLC cells were measured using MTT assays. The invasion ability of NSCLC cells was measured using a Transwell assay. The migration ability of NSCLC cells was measured using a wound healing assay. The cell cycle and cellular apoptosis rates were examined using flow cytometry. -

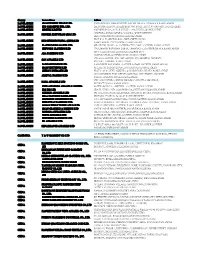

Minimum Wage Standards in China August 11, 2020

Minimum Wage Standards in China August 11, 2020 Contents Heilongjiang ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Jilin ............................................................................................................................................................... 3 Liaoning ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region ........................................................................................................... 7 Beijing......................................................................................................................................................... 10 Hebei ........................................................................................................................................................... 11 Henan .......................................................................................................................................................... 13 Shandong .................................................................................................................................................... 14 Shanxi ......................................................................................................................................................... 16 Shaanxi ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Federal Register/Vol. 84, No. 32/Friday, February 15, 2019/Notices

4436 Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 32 / Friday, February 15, 2019 / Notices molded on the sidewall, that the tire is for from China at the ad valorem rates Circuit’s (CAFC) opinion in Diamond ‘‘Mobile Home Use Only;’’ and (c) the tire is listed below. Sawblades Manufacturers Coalition v. of bias construction as evidenced by the fact DATES: Applicable February 15, 2019. United States, 626 F.3d 1374, 1381 (Fed. that the construction code included in the FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Cir. 2010), the ITC notified Commerce of size designation molded into the tire’s 5 sidewall is not the letter ‘‘R.’’ Yang Jin Chun or Andre Gziryan, AD/ this determination upon remand. In The subject merchandise is currently CVD Operations, Office I, Enforcement Diamond Sawblades Manufacturers classifiable under Harmonized Tariff and Compliance, International Trade Coalition, the CAFC clarified that the Schedule of the United States (HTSUS) Administration, U.S. Department of same procedures for issuance of an subheadings: 4011.20.1015 and Commerce, 1401 Constitution Avenue order and collection of cash deposits 4011.20.5020. Tires meeting the scope NW, Washington, DC 20230; telephone: apply when a material injury description may also enter under the (202) 482–5760 and (202) 482–2201, determination is made upon remand, following HTSUS subheadings: respectively. and that the ITC should provide notice 4011.69.0020, 4011.69.0090, 4011.70.00, to Commerce of its remand 4011.90.80, 4011.99.4520, 4011.99.4590, SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: 4011.99.8520, 4011.99.8590, 8708.70.4530, determination at the time that it is 8708.70.6030, 8708.70.6060, and Background issued, notwithstanding the pendency 6 8716.90.5059.14 In accordance with sections 735(d) of ongoing litigation.