Gender and the Screenplay: Processes, Practices, Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GCWC WAG Creative Writing

GASTON COLLEGE Creative Writing Writing Center I. GENERAL PURPOSE/AUDIENCE Creative writing may take many forms, such as fiction, creative non-fiction, poetry, playwriting, and screenwriting. Creative writers can turn almost any situation into possible writing material. Creative writers have a lot of freedom to work with and can experiment with form in their work, but they should also be aware of common tropes and forms within their chosen style. For instance, short story writers should be aware of what represents common structures within that genre in published fiction and steer away from using the structures of TV shows or movies. Audiences may include any reader of the genre that the author chooses to use; therefore, authors should address potential audiences for their writing outside the classroom. What’s more, students should address a national audience of interested readers—not just familiar readers who will know about a particular location or situation (for example, college life). II. TYPES OF WRITING • Fiction (novels and short stories) • Creative non-fiction • Poetry • Plays • Screenplays Assignments will vary from instructor to instructor and class to class, but students in all Creative Writing classes are assigned writing exercises and will also provide peer critiques of their classmates’ work. In a university setting, instructors expect prose to be in the realistic, literary vein unless otherwise specified. III. TYPES OF EVIDENCE • Subjective: personal accounts and storytelling; invention • Objective: historical data, historical and cultural accuracy: Work set in any period of the past (or present) should reflect the facts, events, details, and culture of its time and place. -

The Ontology and Literary Status of the Screenplay:The Case of »Scriptfic«

DOI 10.1515/jlt-2013-0006 JLT 2013; 7(1–2): 135–153 Ted Nannicelli The Ontology and Literary Status of the Screenplay:The Case of »Scriptfic« Abstract: Are screenplays – or at least some screenplays – works of literature? Until relatively recently, very few theorists had addressed this question. Thanks to recent work by scholars such as Ian W. Macdonald, Steven Maras, and Steven Price, theorizing the nature of the screenplay is back on the agenda after years of neglect (albeit with a few important exceptions) by film studies and literary studies (Macdonald 2004; Maras 2009; Price 2010). What has emerged from this work, however, is a general acceptance that the screenplay is ontologically peculiar and, as a result, a divergence of opinion about whether or not it is the kind of thing that can be literature. Specifically, recent discussion about the nature of the screenplay has tended to emphasize its putative lack of ontological autonomy from the film, its supposed inherent incompleteness, or both (Carroll 2008, 68–69; Maras 2009, 48; Price 2010, 38–42). Moreover, these sorts of claims about the screenplay’s ontology – its essential nature – are often hitched to broader arguments. According to one such argument, a screenplay’s supposed ontological tie to the production of a film is said to vitiate the possibility of it being a work of literature in its own right (Carroll 2008, 68–69; Maras 2009, 48). According to another, the screenplay’s tenuous literary status is putatively explained by the idea that it is perpetually unfinished, akin to a Barthesian »writerly text« (Price 2010, 41). -

Why Does the Screenwriter Cross the Road…By Joe Gilford 1

WHY DOES THE SCREENWRITER CROSS THE ROAD…BY JOE GILFORD 1 WHY DOES THE SCREENWRITER CROSS THE ROAD? …and other screenwriting secrets. by Joe Gilford TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION (included on this web page) 1. FILM IS NOT A VISUAL MEDIUM 2. SCREENPLAYS ARE NOT WRITTEN—THEY’RE BUILT 3. SO THERE’S THIS PERSON… 4. SUSTAINABLE SCREENWRITING 5. WHAT’S THE WORST THAT CAN HAPPEN?—THAT’S WHAT HAPPENS! 6. IF YOU DON’T BELIEVE THIS STORY—WHO WILL?? 7. TOOLBAG: THE TRICKS, GAGS & GADGETS OF THE TRADE 8. OK, GO WRITE YOUR SCRIPT 9. NOW WHAT? INTRODUCTION Let’s admit it: writing a good screenplay isn’t easy. Any seasoned professional, including me, can tell you that. You really want it to go well. You really want to do a good job. You want those involved — including yourself — to be very pleased. You really want it to be satisfying for all parties, in this case that means your characters and your audience. WHY DOES THE SCREENWRITER CROSS THE ROAD…BY JOE GILFORD 2 I believe great care is always taken in writing the best screenplays. The story needs to be psychically and spiritually nutritious. This isn’t a one-night stand. This is something that needs to be meaningful, maybe even last a lifetime, which is difficult even under the best circumstances. Believe it or not, in the end, it needs to make sense in some way. Even if you don’t see yourself as some kind of “artist,” you can’t avoid it. You’re going to be writing this script using your whole psyche. -

Introduction Screenwriting Off the Page

Introduction Screenwriting off the Page The product of the dream factory is not one of the same nature as are the material objects turned out on most assembly lines. For them, uniformity is essential; for the motion picture, originality is important. The conflict between the two qualities is a major problem in Hollywood. hortense powdermaker1 A screenplay writer, screenwriter for short, or scriptwriter or scenarist is a writer who practices the craft of screenwriting, writing screenplays on which mass media such as films, television programs, comics or video games are based. Wikipedia In the documentary Dreams on Spec (2007), filmmaker Daniel J. Snyder tests studio executive Jack Warner’s famous line: “Writers are just sch- mucks with Underwoods.” Snyder seeks to explain, for example, why a writer would take the time to craft an original “spec” script without a mon- etary advance and with only the dimmest of possibilities that it will be bought by a studio or producer. Extending anthropologist Hortense Powdermaker’s 1950s framing of Hollywood in the era of Jack Warner and other classic Hollywood moguls as a “dream factory,” Dreams on Spec pro- files the creative and economic nightmares experienced by contemporary screenwriters hoping to clock in on Hollywood’s assembly line of creative uniformity. There is something to learn about the craft and profession of screenwrit- ing from all the characters in this documentary. One of the interviewees, Dennis Palumbo (My Favorite Year, 1982), addresses the downside of the struggling screenwriter’s life with a healthy dose of pragmatism: “A writ- er’s life and a writer’s struggle can be really hard on relationships, very hard for your mate to understand. -

Rewriting Aristotle: the Uses and Misuses of the Poetics in the Teaching and Practice of Screenwriting

Rewriting Aristotle: the Uses and Misuses of the Poetics in the Teaching and Practice of Screenwriting Brian Dunnigan, Head of Screenwriting, London Film School October 2014 “ All human beings by nature desire knowledge.” Aristotle (Metaphysics) “ Tragedy is essentially an imitation not of persons but of action and of life.” Aristotle (Poetics) “The film language is the most elaborate, the most secret and the most invisible. A good script is a script that you don’t notice. It has vanished. Being a screenwriter is not the last step of a literary adventure but the first step of a film adventure…therefore a screenwriter must know everything about the techniques of how to make a film.” Jean-Claude Carrière I read with interest that amongst the early aims of the Screenwriting Research Network is that of “ interpreting documents intended to describe the screen idea” and a study of “ the interaction of those agents concerned with constructing the screenwork.” We are presumably referring here to the screenplay and the screenwriters and filmmakers working toward the creation of a film. The lively, anxious, imaginative humans who struggle to express themselves in conversation and debate, to shape a meaningful narrative for an audience. As an educator involved with curious and often confused humans trying to understand what it is they have to say about the world - I find that description of theoretical practice misses too much of what excites me about storytelling and cinema. This is partly language and partly to do with how as a writer and teacher one prefers to think about the process of filmmaking. -

A Genre Is a Conventional Response to a Rhetorical Situation That Occurs Fairly Often

What is a genre? A genre is a conventional response to a rhetorical situation that occurs fairly often. Conventional does not necessarily mean boring. Instead, it means a recognizable pattern for providing specific kinds of information for an identifiable audience demanded by circumstances that come up again and again. For example, new movies open almost every week. Movie makers pay for advertising to entice viewers to see their movies. Genres have a purpose. While consumers may learn about a movie from the ads, they know they are getting a sales pitch with that information, so they look for an outside source of information before they spend their money. Movie reviews provide viewers with enough information about the content and quality of a film to help them make a decision, without ruining it for them by giving away the ending. Movie reviews are the conventional response to the rhetorical situation of a new film opening. Genres have a pattern. The movie review is conventional because it follows certain conventions, or recognized and accepted ways of giving readers information. This is called a move pattern. Here are the moves associated with that genre: 1. Name of the movie, director, leading actors, Sometimes, the opening also includes the names of people and companies associated with the film if that information seems important to the reader: screenwriter, animators, special effects, or other important aspects of the film. This information is always included in the opening lines or at the top of the review. 2. Graphic design elements---usually, movie reviews include some kind of art or graphic taken from the film itself to call attention to the review and draw readers into it. -

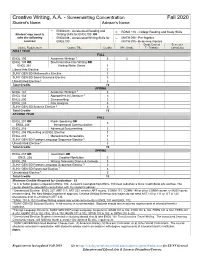

Creative Writing, A.A. - Screenwriting Concentration Fall 2020 Student's Name: Advisor's Name

Creative Writing, A.A. - Screenwriting Concentration Fall 2020 Student's Name: Advisor's Name: ENGL049 - Accelerated Reading and RDNG 116 - College Reading and Study Skills Student may need to Writing Skills for ENGL100 OR take the following ENGL098 - Accelerated Writing Skills for MATH 090 - Pre-Algebra courses: ENGL100 MATH 095 - Beginning Algebra Grade Earned Semester Course Requirement Course Title Credits Min. Grade T - Transfer Completed FIRST YEAR FALL ENGL 100 Academic Writing I 1 3 C ENGL 135 OR Short Narrative Film Writing OR ENGL 261 Visiting Writer Series 1 Liberal Arts Elective 3 SUNY GEN ED Mathematics Elective 3 SUNY GEN ED Social Sciences Elective 3 Unrestricted Elective 2 3 Total Credits 16 SPRING ENGL 101 Academic Writing II 3 3 ENGL 102 Approaches to Literature 3 3 ENGL 200 Screenwriting 3 ENGL 233 Film Analysis 3 SUNY GEN ED Science Elective 4 3 Total Credits 15 SECOND YEAR FALL ENGL 201 OR Public Speaking OR 3 ENGL 204 Interpersonal Communication ENGL 216 Advanced Screenwriting 3 ENGL 256 Playwriting or ENGL Elective 3 ENGL 274 Marketing the Screenplay 1 SUNY GEN ED Foreign Language Sequence Elective 5 3 Unrestricted Elective 6 3 Total Credits 16 SPRING ENGL 237 OR Journalism OR ENGL 258 Creative Nonfiction 3 ENGL 255 Writing Television Drama & Comedy 3 5 SUNY GEN ED Foreign Language Sequence Elective 3 SUNY GEN ED Restricted Elective 7 3 Unrestricted Elective 6 3 Total Credits 15 Minimum Credits Required for Graduation: 62 1 A C or better grade is required in ENGL 100. A student exempted from ENGL 100 must substitute a three credit liberal arts elective. -

Writer's Workshop (WRWS) 1

Writer's Workshop (WRWS) 1 WRWS 2400 FOUNDATIONS OF SCREENWRITING (3 credits) WRITER'S WORKSHOP This course introduces the student to the foundational elements of screenwriting. The student will learn and practice the techniques of conveying a story in images and sound, creating characters with human (WRWS) motives and conflicts, editing for economy and thematic significance. Proper script formatting will be taught and expected. WRWS 1010 CONTEMPORARY WRITERS:IN PERSON IN PRINT (3 Prerequisite(s)/Corequisite(s): English 1160 or equivalent. credits) Distribution: Humanities and Fine Arts General Education course An introduction to reading contemporary literature by studying the ways in which a writer shapes a poem or tale to communicate with an audience. WRWS 2600 BASIC SCREENWRITING AND TELEVISION WRITING Emphasizes the most contemporary prose and poetry and includes a series STUDIO (4 credits) of readings and classroom visits by guest writers whose books are the texts This studio introduces the fundamentals of screenwriting. The student will for the class. produce a pitch, outline and completed industry-standard screenplay that Prerequisite(s)/Corequisite(s): ENGL1160 or equivalent. Not open to conveys a story, creates characters, and is edited for economy and theme. non-degree graduate students. Proper script formatting will be taught and expected. Prerequisite(s)/Corequisite(s): WRWS 2050, or WRWS 2060. Not open WRWS 1500 INTRODUCTION TO CREATIVE WRITING (3 credits) to non-degree graduate students. An introduction for non-majors in creative writing to the art and craft of writing fiction, poetry, and creative nonfiction. Follows a workshop format WRWS 3000 SELECTED TOPICS IN WRITING (1-3 credits) based on individual and group critique of students' writing, discussion This course presents selected theoretical and practical approaches of principles and techniques of the craft, and reading and analysis of to crafting one or more the following genres: poetry, fiction, creative instructive literary examples. -

BHA Creative Writing Concentration

BHA-Creative Writing Fall 2021 Bachelor of Humanities and Arts (BHA) Dietrich College (DC) Concentration in Creative Writing 81 units (minimum) Advisor: Laura E. Donaldson, Baker Hall 259, 412-268-3089, [email protected] In the Creative Writing concentration, BHA students develop their talents in writing fiction, poetry and other imaginative forms. While studying with faculty members who are practicing poets and prose writers, students read widely in literature, explore the resources of their imaginations, sharpen their critical and verbal skills, and develop a professional attitude toward their writing. The Creative Writing program is based on a conservatory model, made up of faculty and students who have an intense commitment to their work. Students in the Creative Writing concentration are required to take two of the introductory Survey of Forms courses, ideally in their sophomore year. Choices include Poetry (76-265), Fiction (76-260), Screenwriting (76-269) and Creative Nonfiction (76-261). In order to proceed into the upper level courses in the concentration (and in each of the genres), students must do well in these introductory courses (receive a grade of A or B). After completing the Survey of Forms courses, students take four workshops in fiction, poetry, screenwriting or nonfiction. At least two of the workshops must be taken in a single genre. In the writing workshops, students develop their critical and verbal abilities through close writing and analysis of poems, stories and other literary forms. Their work is critiqued and evaluated by peers and the faculty. BHA students take 9 courses in their DC concentration, for a minimum of 81 units. -

Hollywood Safari Navigating Screenwriting Books & Theory

Hollywood Safari Navigating Screenwriting Books & Theory John Fraim John Fraim GreatHouse Stories 1702 Via San Martino Palm Desert, CA 92260 [email protected] 760-844-2595 (c) 2014 – John Fraim 1 Table of Contents Introduction 4 1. Personal School 8 William Goldman Adventures in the Screen Trade 2. Step School 9 John Truby Anatomy of Story Blake Snyder Save the Cat 3. Ancient School 11 Michael Tierno Aristotle’s Poetics for Screenwriters 4. Drama School 14 Lajos Egri The Art of Dramatic Writing 5. Mythology School 15 Christopher Vogler The Writers Journey Joseph Campbell Hero With A Thousand Faces 6. Sequence School 17 Paul Gulino The Hidden Structure of Successful Screenplays Eric Edson The Story Solution 7. Plot School 20 George Polti Thirty-Six Dramatic Situations William Wallace Cook Plotto Tom Sawyer & Arthur David Weingarten Plots Unlimited Christopher Booker Seven Basic Plots 8. Psychology School 25 William Indick Psychology for Screenwriters Peter Dunne Emotional Structure Pamela Jaye Smith Inner Drives 9. Principles School 29 Robert McKee Story David Howard and Edward Mabley The Tools of Screenwriting Richard Walter Essentials of Screenwriting Lew Hunter Screenwriting 434 2 Carson Reeves ScriptShadow Secrets 10. Visual School 33 Appendix A 36 Bibliography of Screenwriting Books Appendix B 38 John Truby’s 7/22 Step Sequence in Anatomy of Story Appendix C 39 Blake Snyder’s 15 Step Sequence in Save the Cat! Appendix D 42 Towards a Graphic Map of Screenwriting Books Appendix E 43 Eric Edson’s Structure Steps Appendix F 44 Daniel’s Sequence Approach Appendix G 45 The Thirty-Six Dramatic Situations Appendix H 48 McKee’s Three Types of Screenplay Structure Comments 49 About Author John Fraim 50 3 Introduction “Stories are at the heart of humanity and are the repository of our diverse cultural heritage. -

Course Outline: Screenwriting the MA in Screenwriting Is a Specialisation

Course outline: Screenwriting The MA in Screenwriting is a specialisation within the broader MA in Film and Television. The graduating screenwriter’s portfolio will consist of at least the three following (or an agreed equivalent): a short script – either for a short fiction or animation graduation film, or an episode of a half hour soap, sitcom, radio drama or stage play a television series episode script, either multi-stranded or stand alone a feature length script for film or television, either original or adaptation The first year of the course establishes basic storytelling and introduces writers to a range of writing situations: short fiction films, short animations, short stage plays, original formats for TV series and Games. Also, to prepare the ground for developing feature film subjects, different forms are explored: realism, non-naturalism, non- linear narrative and fiction derived from fact. The groundwork is set for developing a feature screenplay. The second year is devoted to the full-length screenplay, the hour long television script, plus any collaboration on short fiction or animation graduation films or on a graduation project with the Games Department. At the time of graduation, the writers’ work is also showcased separately to the screenings. The course ends with extensive introductions to the industry with preparation on the practicalities and legalities of working. In this process, writers learn to pitch the projects in their portfolio. Year One Overview of Screenwriting Curriculum – First Year Assessed Modules and more informal Workshops will cover these issues: Term 1 the screenwriter’s screen language – Telling the Story in Pictures - a general introduction to all the different kinds of writing that will be covered in the course – features, TV, radio, theatre, animation, games, etc. -

Film & TV Screenwriting (SCWR)

Film & TV Screenwriting (SCWR) 1 SCWR 122 | SCRIPT TO SCREEN (FORMERLY DC 224) | 4 quarter hours FILM & TV SCREENWRITING (Undergraduate) This analytical course examines the screenplay's evolution to the screen (SCWR) from a writer's perspective. Students will read feature length scripts of varying genres and then perform a critical analysis and comparison of the SCWR 100 | INTRODUCTION TO SCREENWRITING (FORMERLY DC 201) | text to the final produced versions of the films. Storytelling conventions 4 quarter hours such as structure, character development, theme, and the creation of (Undergraduate) tension will be used to uncover alterations and how these adjustments This course is an introduction to and overview of the elements of theme, ultimately impacted the film's reception. plot, character, and dialogue in dramatic writing for cinema. Emphasis is SCWR 123 | ADAPTATION: THE CINEMATIC RECRAFTING OF MEANING placed on telling a story in terms of action and the reality of characters. (FORMERLY DC 235) | 4 quarter hours The difference between the literary and visual medium is explored (Undergraduate) through individual writing projects and group analysis. Films and scenes This course explores contemporary cinematic adaptations of literature examined in this class will reflect creators and characters from a wide and how recent re-workings in film open viewers up to critical analysis range of diverse backgrounds and intersectional identities. Development of the cultural practices surrounding the promotion and reception of of a synopsis and treatment for a short theatrical screen play: theme, plot, these narratives. What issues have an impact upon the borrowing character, mise-en-scene and utilization of cinematic elements.