The EU's Anti-Money Laundering Policy in the Banking Sector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

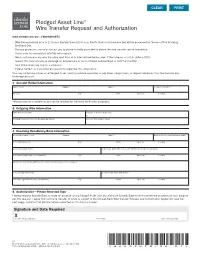

Pledged Asset Line® Wire Transfer Request and Authorization | 1-800-838-6573

Pledged Asset Line® Wire Transfer Request and Authorization www.schwab.com/pal | 1-800-838-6573 • Wire forms received prior to 1:30 p.m. Eastern time (10:30 a.m. Pacific time) on a Business Day will be processed by the end of the following Business Day. • For your protection, we must contact you by phone to verify your identity before the wire transfer can be completed. • There is no fee associated with this wire request. • We do not process any wire transfers sent from or to international banks, even if the currency is in U.S. dollars (USD). • Submit this form via secure message on Schwab.com or fax to Charles Schwab Bank at 1-877-300-6933. • Your initial draw may require a minimum. • Please contact us if you have any questions regarding this information. You may not borrow money on a Pledged Asset Line to purchase securities or pay down margin loans, or deposit advances from the line into any brokerage account. 1. Account Holder Information Name (First) (Middle) (Last) Telephone Number* Address City State Zip Code Country *Please provide a number so you can be reached for call-back verification purposes. 2. Outgoing Wire Information Date Wire to Be Sent Amount of Wire (in USD only) $ Pledged Asset Line Account Number (12 digits) Account Title (owner name) 3. Receiving Beneficiary/Bank Information Beneficiary Name (First) (Middle) (Last) Beneficiary Account Number at Bank Beneficiary Address City State Zip Code Country Beneficiary Bank Name Beneficiary Bank ABA or Account Number at Send-Through Bank Beneficiary Bank Address (if available) City State Zip Code Country Additional Instructions (Attention to, Customer Reference, Phone Advice) Send-Through Bank Name Send-Through Bank ABA Number Send-Through Bank Address (if available) City State Zip Code Country 4. -

Implementing the Protocol 36 Opt

September 2012 Opting out of EU Criminal law: What is actually involved? Alicia Hinarejos, J.R. Spencer and Steve Peers CELS Working Paper, New Series, No.1 http://www.cels.law.cam.ac.uk http://www.cels.law.cam.ac.uk/publications/working_papers.php Centre for European Legal Studies • 10 West Road • Cambridge CB3 9DZ Telephone: 01223 330093 • Fax: 01223 330055 • http://www.cels.law.cam.ac.uk EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Protocol 36 to the Lisbon Treaty gives the UK the right to opt out en bloc of all the police and criminal justice measures adopted under the Treaty of Maastricht ahead of the date when the Court of Justice of the EU at Luxembourg will acquire jurisdiction in relation to them. The government is under pressure to use this opt-out in order to “repatriate criminal justice”. It is rumoured that this opt-out might be offered as a less troublesome alternative to those are calling for a referendum on “pulling out of Europe”. Those who advocate the Protocol 36 opt-out appear to assume that it would completely remove the UK from the sphere of EU influence in matters of criminal justice and that the opt-out could be exercised cost-free. In this Report, both of these assumptions are challenged. It concludes that if the opt-out were exercised the UK would still be bound by a range of new police and criminal justice measures which the UK has opted into after Lisbon. And it also concludes that the measures opted out of would include some – notably the European Arrest Warrant – the loss of which could pose a risk to law and order. -

BANKING FEES All Fees Include GCT ACCOUNT OPENING SAVINGS ACCOUNT

JMMB BANK BANKING FEES All fees include GCT ACCOUNT OPENING SAVINGS ACCOUNT CURRENT ACCOUNT Cheque Leaves Acquisition (Retail) J$2912.50 Cheque Leaves Acquisition (SME) J$5825.00 Cheque Leaves Acquisition (Corporate) J$17,475.00 Monthly Service Charge FREE Cheque Writing J$50.00 Returned Cheque (Own Bank)/Chargeback Item J$873.75 J$450.00 Stop Payment (Own Bank) J$5000.00 maximum TRANSACTION RELATED CASH DEPOSITS 1% + GCT (1.17%) on investment/deposits equal to 1,500 units or above in each currency, subject to a per client limit of 500 units per business day Cash Deposits - Foreign Currency and 1,500 units per calendar month. Cash Deposits in excess of J$1M Free CHEQUE DEPOSITS Returned Cheque J$640.75 Cheque Deposit - Collection Item (US) US$6.99 + Other Bank Charge J$640.75 Foreign Cheque Returned + Other Bank Charge Foreign Cheque Stop Payment US$14.88+ Other Bank Charge Cheque Deposit - Same Day Value (JMMB Bank Cheques) Free CASH WITHDRAWALS Cash Withdrawals up to J$1,000,000.00 Free CHEQUE WITHDRAWALS TRANSFERS WITHIN JMMB BANK Transfer Between Own Accounts (Internal Transfer) Free TRANSFERS TO AND FROM LOCAL INSTITUTIONS Returned/Recalled Electronic Transfers (Local) J$500.00 Transfer to other financial institution/ Third party (Local ACH) J$25.00 Wire - Incoming and Outgoing RTGS Transfers J$250.00 TRANSFERS TO AND FROM INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTIONS International Wire Transfer -Inbound - USD US$23.30 International Wire Transfer -Inbound - GBP n/a International Wire Transfer -Inbound - CAD n/a International Wire Transfer -Inbound -

Brexit, the “Area of Freedom, Security, and Justice” and Migration

EU Integration and Differentiation for Effectiveness and Accountability Policy Briefs No. 3 December 2020 Brexit, the “Area of Freedom, Security, and Justice” and Migration Emmanuel Comte This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 822622 Brexit, the “Area of Freedom, Security, and Justice” and Migration Emmanuel Comte Abstract This policy brief focuses on EU–UK negotiations on the movements of third-country nationals. It presents the formation of preferences of both sides and creates a map of existing external differentiation in this area, which supplies models for the future EU–UK relationship. Current nego- tiating positions show the continuation of previous trends and the po- tential for close cooperation. This policy brief details two scenarios of cooperation. Close cooperation would continue the current willingness to cooperate and minimise policy changes after the transition period. Loose cooperation could stem from the collapse of trade talks, breaking confidence between the two sides and resulting in a suboptimal scena- rio for each of them. No scenario, however, is likely to result in signifi- cantly lower effectiveness or cohesion in the EU. The UK will always be worse off in comparison to EU membership – particularly under loose cooperation. Emmanuel Comte is Senior Research Fellow at the Barcelona Centre for Internatio- nal Affairs (CIDOB). 2 | Brexit, the “Area of Freedom, Security, and Justice” and Migration Executive summary The UK has wanted for 30 years to cooperate with other EU countries and EU institutions to keep third-country immigration under control. Brexit has not changed this preference. -

Enterprising Criminals Europe’S Fight Against the Global Networks of Financial and Economic Crime 2 03 04 Foreword Key Findings 05 07

EFECC European Financial and Economic Crime Centre Enterprising criminals Europe’s fight against the global networks of financial and economic crime 2 03 04 Foreword Key findings 05 07 Setting the (crime) scene What is happening today that may impact the economic and financial crimes of tomorrow? › Technology drives change in behaviours › Economic downturns create opportunities for crime › Corruption 09 11 Intellectual property Fraud crime: counterfeit and › Tax Fraud substandard goods 16 19 Money laundering A European response - › Money laundering techniques The European Financial and Economic Crime Centre at Europol 3 Foreword CATHERINE DE BOLLE Executive Director, Europol The fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic has weakened our economy and created new vulnerabilities from which crime can emerge. Economic and financial crime, such as various types of fraud, money laundering, intellectual property crime, and currency counterfeiting, is particularly threatening during times of economic crisis. Unfortunately, this is also when they become most prevalent. The European Economic and Financial Crime Centre (EFECC) at Europol will strengthen Europol’s ability to support Member States’ and partner countries’ law enforcement authorities in fighting the criminals seeking to profit from economic hardship. EFECC will serve as a platform and toolbox for financial investigators across Europe. We look forward to making lasting partnerships with them and fighting economic and financial crime together. 4 COMPANY Key findings A 1 2 » Money laundering and criminal finances are the engines of organised crime. ithout them criminals would not be able to make use of the illicit profits from their various serious and organised crime activities in the EU. -

Understanding Public Euroscepticism

Firenze University Press www.fupress.com/qoe Understanding public Euroscepticism Citation: Simona Guerra (2020) Under- standing public Euroscepticism. Quad- Simona Guerra erni dell’Osservatorio elettorale – Ital- ian Journal of Electoral Studies 83(2): University of Surrey, United Kingdom, 0000-0003-3911-258X 45-56. doi: 10.36253/qoe-9672 E-mail: [email protected] Received: September 4, 2020 Abstract. Euroscepticism has become more and more embedded both at the EU and Accepted: December 17, 2020 national levels (Usherwood et al. 2013) and persistent across domestic debates (Ush- erwood and Startin 2013). This study presents an in-depth analysis of contemporary Published: December 23, 2020 narratives of Euroscepticism. It first introduces its question related to understanding Copyright: © 2020 Simona Guerra. This public Euroscepticism, following the British EU referendum campaign and outcome, to is an open access, peer-reviewed then present the established literature, and the analysis of the British case study. A sur- article published by Firenze Univer- vey run in Britain in May 2019 shows that, as already noted by Oliver Daddow (2006, sity Press (http://www.fupress.com/qoe) 2011), Euroscepticism is very much identifiable in the traditional narratives of Europe and distributed under the terms of the as the Other. Context accountability (Daddow 2006) is still cause for concern in Britain Creative Commons Attribution License, and by assuming a more positive view of a European Britain (Daddow 2006) does not which permits unrestricted use, distri- make the debate more informed. Images, narratives and specific issues to reform the bution, and reproduction in any medi- um, provided the original author and Eurosceptic toolbox into a more neutral, but informative, instrument could be applied source are credited. -

Digital Is the New Normal!

DIGITAL IS THE NEW NORMAL! Acting together to better handle cross-border electronic evidence VIRTUAL SIDE EVENT organized at the margins of the 30th United Nations Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice (CCPCJ) click or scan code to 17 MAY 2021 14:10 (CET) access the event In collaboration with: OBJECTIVE This side event will provide a forum to share results on the impact of the UNODC-CTED-EUROPOL-EUROJUST-EJN Partnership in advancing international law enforcement and judicial cooperation through the development of tools such as the second version of the Practical Guide for Requesting Electronic Evidence Across Borders, and the model request forms on Preservation, Emer- gency and Voluntary Disclosure. The side event will also present the mapping information of communication service providers and will be the occasion to present the SHERLOC Electronic Evidence Hub. TARGET AUDIENCE The event will target practitioners across the criminal justice systems, specifically those involved in handling electronic evidence in the context of criminal proceedings involving multiple jurisdictions. DIGITAL IS THE NEW NORMAL! 17 MAY 2021 Acting together to better handle 14:10 (CET) cross-border electronic evidence AGENDA Moderator: Ms. Arianna Lepore Coordinator, UNODC Global Initiative on Handling Electronic Evidence Across Borders 14:10 to 14:30 High Level Segment 14:30 to 15:00 Technical Segment Opening remarks by: PRESENTATION OF THE PRACTICAL GUIDE FOR REQUESTING Ms. Ghada Waly ELECTRONIC EVIDENCE ACROSS BORDERS UNODC Executive Director Mr. Daniel Suter UNODC Consultant, Terrorism Prevention Branch Ms. Michèle Coninsx United Nations Assistant Secretary-General and Executive Director PRESENTATION OF CONTRIBUTIONS AND THE NEW MODEL FORMS of the Counter-Terrorism Committee Executive Directorate Mr. -

Fedwire® Funds Service Produc T Sheet

Fedwire® Funds Service The Fedwire Funds Service is the premier wire-transfer service that financial institutions and businesses rely on to send and receive time-critical, same-day payments. When it absolutely matters, the Fedwire Funds Service is the one to trust to execute your individual payments with certainty and finality. As a Fedwire Funds Service participant, you can pricing and permits the Federal Reserve Banks to use this real-time, gross-settlement system to send take certain actions, including requiring collateral and and receive payments for your own account or on monitoring account positions in real time. Detailed behalf of corporate or individual clients to make information on the Federal Reserve’s daylight cash concentration payments, to settle commercial overdraft policies can be found in the Guide to payments, to settle positions with other financial the Federal Reserve’s Payment System Risk Policy, institutions or clearing arrangements, to submit available online at www.federalreserve.gov. federal tax payments or to buy and sell federal funds. Security and Reliability When sending a payment order to the Fedwire The Fedwire Funds Service is designed to deliver the Funds Service, a Fedwire participant authorizes its reliability and security you know and trust from the Federal Reserve Bank to debit its master account Federal Reserve Banks. Service resilience is enhanced for the amount of the transfer. If the payment order through out-of-region backup facilities for the is accepted, the Federal Reserve Bank holding the Fedwire Funds Service application, routine testing master account of the Fedwire participant that is of business continuity procedures across a variety of to receive the transfer will credit the same amount contingency situations and ongoing enhancements to that master account. -

International Wire Transfer Quick Tips &

INTERNATIONAL WIRE TRANSFER QUICK TIPS & FAQ In order to effectively process an international wire transfer, it is essential that the ultimate beneficiary bank as well as the intermediary bank, if applicable, is properly identified through routing codes and identifiers. However, countries have adopted varying degrees of sophistication in how they route payments between their financial institutions, making this process sometimes challenging. For this reason, these Quick Tips have been created to help you effectively process international wires. By including the proper routing information specific to a country when processing a wire transaction, you can ensure your wires will be processed correctly. Depending on the destination of an international wire transfer, the following identifiers should be used to identify the beneficiary bank and intermediary bank, as applicable. SWIFT code: Stands for ‘Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Communications.’ Within the international transfer world, SWIFT is a universal messaging system. SWIFTs are BICs (Bank Identifier Code) connected to the S.W.I.F.T. network and either take an eleven digit or eight digit format. A digit other than “1” will always be in the eighth position. Swift codes always follow this format: • Character 1-4 are alpha and refer to the bank name • Characters 5 and 6 are alpha and refer to the currency of the country • Characters 7-11 can be alpha, numeric or both to designate the bank location (main office and/or branch) Example: DEUTDEDK390 (w/branch); SINTGB2L (w/o branch) BIC: A universal telecommunication address assigned and administered by S.W.I.F.T. BICs are not connected to the S.W.I.F.T. -

Gathering Details for Outgoing Wires

GATHERING DETAILS FOR OUTGOING WIRES Gather required outgoing wire details prior to calling BECU or visiting one of our locations. To find a location near you, visit becu.org/locations. Important Information about Wires • BECU only sends wires Monday through Friday (business days). • BECU does not send wires Saturday, Sunday, or federal holidays (non-business days). • Domestic Wires and International Wires requested by 1:00 p.m. (PT), Monday through Friday, will be sent on the current business day (if all requirements are met). • Domestic Wires requested after 1:00 p.m. (PT), Monday through Friday, or any time on Saturday or a non-business day, will be sent the next business day (if all requirements are met). Domestic Wire Requests • To submit a Domestic wire request in person, visit a BECU location, Monday through Friday, 9:00 a.m. – 6:00 p.m. or Saturday, 9:00 a.m. – 1:00 p.m. (PT). • To submit a Domestic wire request by phone, call a BECU representative toll-free at 800-233-2328, Monday through Friday, 7:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. (PT). • A $25.00 wire fee applies, which will be posted as a separate transaction and debited from the same account the wire is drawn on. International Wire Requests • To submit an International wire request in person, visit a BECU location, Monday through Friday, 9:00 a.m. – 1:00 p.m. (PT). • To submit an International wire request by phone, call a BECU representative at 800-233-2328, Monday through Friday, 7:00 a.m. -

Anniversary Publication

Ten Years of Europol 1999-2009 TEN YEARS OF EUROPOL, 1999-2009 Europol Corporate Communications P.O. Box 90850 2509 LW The Hague The Netherlands www.europol.europa.eu © European Police OfÞ ce, 2009 All rights reserved. Reproduction in any form or by any means is allowed only with the prior permission of Europol Editor: Agnieszka Biegaj Text: Andy Brown Photographs: Europol (Zoran Lesic, Bo Pallavicini, Max Schmits, Marcin Skowronek, Europol archives); EU Member States’ Law Enforcement Authorities; European Commission; European Council; Participants of the Europol Photo Competition 2009: Kristian Berlin, Devid Camerlynck, Janusz Gajdas, Jean-François Guiot, Lasse Iversen, Robert Kralj, Tomasz Kurczynski, Antte Lauhamaa, Florin Lazau, Andrzej Mitura, Peter Pobeska, Pawel Ostaszewski, Jorgen Steen, Georges Vandezande Special thanks to all the photographers, EU Member States’ Law Enforcement Authorities and Europol Liaison Bureaux for their contributions 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 7 I. Birth of an Idea, 1991-1998 11 1. Ideas behind Europol: Tackling International Crime 11 2. Maastricht Treaty: the ‘Founding Article’ 12 3. First Step: the Europol Drugs Unit 12 4. The Hague: a Fitting Location 13 5. Formal Status: the Europol Convention 14 6. European Union: New Members and a New Treaty 15 II. The First Years, 1999-2004 21 1. Facing the Challenges: Stabilisation and Consolidation 21 2. Changing Priorities, Flexible Organisation 24 3. Information Exchange and Intelligence Analysis: Core Business 27 4. The Hague Programme: Positioning Europol at the Centre of EU Law Enforcement Cooperation 34 5. Casting the Net Wider: Cooperation Agreements with Third States and Organisations 36 6. Europol’s Most Important Asset: the Staff and the ELO Network 37 III. -

Domestic & International Wire Transfer Request for Line of Credit

TM DOMESTIC & INTERNATIONAL WIRE TRANSFER REQUEST FOR LINE OF CREDIT By completing and signing this request form, I authorize The Bancorp Bank (Bank) to make a one-time electronic wire transfer using funds advanced from my Line of Credit account and as such understand the credit advance under my Line of Credit is subject to all terms of the Line of Credit Agreement. Please complete the information below to authorize a written wire transfer request. (International information required only if applicable). An incomplete form will delay processing. Fee(s) may be assessed by the receiving, intermediary and/or beneficiary financial institution(s) for a wire transfer returned for insufficient or incorrect information which you provided that prevented the funds from being applied to the beneficiary account. The fee(s) may vary and will be deducted from the funds returned to your Line of Credit account by the financial institution(s) charging the fee(s). NOTE: Wire transfer requests received prior to 4:00 PM ET will be processed the same business day if funds are available and call back verification has been completed. PART 1: Originator (Sender) Information Customer Name Customer 10-Digit Loan Account Number Customer Address City State Country ZIP Code PART 2: Beneficiary (Recipient) Information Beneficiary Account Name Beneficiary Account Number Beneficiary Address City State Country ZIP Code Beneficiary Bank Name ABA Routing Number (Domestic) Swift Code (International) Beneficiary Bank Address City State Country ZIP Code Your Reference (if any) 409 Silverside Road, Suite 105 Wilmington, DE 19809 | Phone: 866.792.5412 | Fax: 302.791.5787 | www.seicashaccess.com REQ0001506 09/2020 145 DOMESTIC & INTERNATIONAL WIRE TRANSFER REQUEST FOR LINE OF CREDIT Page 2 of 5 PART 3: Intermediary Bank Information If requesting an international U.S.