Th E Book to Come

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

TOKYO IDOLS - a film by KYOKO MIYAKE

TOKYO IDOLS - A film by KYOKO MIYAKE Distributed in Canada by Films We Like Bookings and General Inquries: mike@filmswelike.com Publicity and Media: mallory@filmswelike.com Press kit and high rez images: http://www.filmswelike.com/films/tokyo-idols LOGLINE Girl bands and their pop music permeate every moment of Japanese life. Following an aspiring pop singer and her fans, Tokyo Idols explores a cultural phenomenon driven by an obsession with young female sexuality, and the growing disconnect between men and women in hyper-modern societies SYNOPSIS “IDOLS” has fast become a phenomenon in Japan as girl bands and pop music permeate Japanese life. TOKYO IDOLS - an eye-opening film gets at the heart of a cultural phenomenon driven by an obsession with young female sexuality and internet popularity. This ever growing phenom is told through Rio, a bona fide "Tokyo Idol" who takes us on her journey toward fame. Now meet her “brothers”: a group of adult middle aged male super fans (ages 35 - 50) who devote their lives to following her—in the virtual world and in real life. Once considered to be on the fringes of society, the "brothers" who gave up salaried jobs to pursue an interest in female idol culture have since blown up and have now become mainstream via the internet, illuminating the growing disconnect between men and women in hypermodern societies. With her provocative look into the Japanese pop music industry and its focus on traditional beauty ideals, filmmaker Kyoko Miyake confronts the nature of gender power dynamics at work. As the female idols become younger and younger, Miyake offers a critique on the veil of internet fame and the new terms of engagement that are now playing out IRL around the globe. -

Deb Westbury

cNº4 1998 ISSNo 1328-2107 r d i t e Poetry and Poetics Review $ Denis Mizzi, Untitled. 5 Adam Aitken interviews Martin Harrison Kevin Hart on Experience and Transcendence and the poetry of Tomas Tranströmer Simon Patton on Jennifer Compton’s hammer! Adam Aitken Interview with Martin Harrison 3 CORDITE Poetry and Poetics Review A quarterly review of Australian poetry Kevin Hart Experience and Transcendence– the poetry of Tomas Tranströmer 10 Publisher CORDITE is published by CORDITE PRESS INC. Simon Patton Compton’s Hammer 23 Editors Adrian Wiggins, Margie Cronin & Chris Andrews Mortal 15 Jennie Kremmer Review Editors Margie Cronin & Dominic Adrift 15 Fitzsimmons John Ashbery The Pathetic Fallacy 4 Interview Editor Bruce Williams Performance Editor Phil Norton Paola Bilbrough Canvastown 13 Picture Editor Sue Bower Peter Boyle Everyday 14 Managing Editor Adrian Wiggins Two translations of Octavio Paz 21 Associate Editor Britta Deuschl Founding Editors Peter Minter & Adrian Wiggins joanne burns shelf life 4 Special Thanks The Arts Law Centre, Richard truce: the humid handshake 19 Mohan, Ivor Indyk, Allan Dean. Jennifer Compton Safe House 22 Printer Marrickville Newspapers Tricia Dearborn schlieren lines 8 18–22 Murray St, Marrickville NSW 2204 Dan Disney Two poems 6 Subscription You can receive four issues of CORDITE at only $20 Keri Glastonbury Rent Boy 8 for humans or $40 for institutions. Send a cheque or Pulp 10 money order payable to CORDITE PRESS INC at the address below. Philip Harvey Q 20 Contribution Z back cover Contributions of long articles, essays or interviews should be discussed with the editors before submis- Lisa Jacobson Evolutionary Tales Nº1: sion. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses 'A forest of intertextuality' : the poetry of Derek Mahon Burton, Brian How to cite: Burton, Brian (2004) 'A forest of intertextuality' : the poetry of Derek Mahon, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1271/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk "A Forest of Intertextuality": The Poetry of Derek Mahon Brian Burton A copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Submitted as a thesis for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Durham Department of English Studies 2004 1 1 JAN 2u05 I Contents Contents I Declaration 111 Note on the Text IV List of Abbreviations V Introduction 1 1. 'Death and the Sun': Mahon and Camus 1.1 'Death and the Sun' 29 1.2 Silence and Ethics 43 1.3 'Preface to a Love Poem' 51 1.4 The Terminal Democracy 59 1.5 The Mediterranean 67 1.6 'As God is my Judge' 83 2. -

James M. Black and Friends, Contributions of Williamsport PA to American Gospel Music

James M. Black and Friends Contributions of Williamsport PA to American Gospel Music by Milton W. Loyer, 2004 Three distinctives separate Wesleyan Methodism from other religious denominations and movements: (1) emphasis on the heart-warming salvation experience and the call to personal piety, (2) concern for social justice and persons of all stations of life, and (3) using hymns to bring the gospel message to people in a meaningful way. All three of these distinctives came together around 1900 in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, in the person of James M. Black and the congregation at the Pine Street Methodist Episcopal Church. Because there were other local persons and companies associated with bands, instruments and secular music during this time, the period is often referred to as “Williamsport’s Golden Age of Music.” While papers have been written on other aspects of this musical phenomenon, its evangelical religious component has generally been ignored. We seek to correct that oversight. James Milton Black (1856-1938) is widely known as the author of the words and music to the popular gospel song When the Roll is Called Up Yonder . He was, however, a very private person whose failure to leave much documentation about his work has frustrated musicologists for decades. No photograph of him suitable for large-size reproduction in gospel song histories, for example, is known to exist. Every year the United Methodist Archives at Lycoming College expects to get at least one inquiry that begins, “I just discovered that James M. Black was a Methodist layperson from Williamsport, could you please tell me…” We now attempt to bring together all that is known about the elusive James M. -

Megamorphs4.Pdf

Help me." I tried to get up. There was a body lying on me. Hork-Bajir. His wrist blade was jammed against my side. I tried to lift up with all four legs, lift the dead thing off me. But I only had three legs. My left hind leg lay across the bright-lit floor, a curiosity, a macabre relic. Tiger's paw. OCRed By Arpit Nathany I tried to slide. That was better. The floor was wood, highly polished. Slick with blood, animal, alien, human. I reached out with my two front paws, extended the claws, and dug them into the wood. They didn't catch at first. But then my right paw chewed wood and I gained traction. A voice said, "Help. Please help me." 1 I dragged myself slowly, carefully, gingerly out I felt a wave of relief. The last I'd seen of from beneath the bladed alien. The pain in the Cassie she was in trouble. missing leg was intense. Don't let anyone ever In the distance, out through the big doors, tell you animals don't feel pain. I've been a lot of down the dark hallway, I heard the hoarse vocals animals. Mostly they feel pain. of a grizzly bear. Rachel. Not fighting, not any <Jake? Jake?> more, just raging, raging. Roaring with the frus It was Cassie. <Yeah. I'm here.> tration of a mad beast looking for fresh victims With a lurch I was free of the weight press and finding none. ing me down. I rose, shaky on three legs. -

September”—Earth Wind & Fire (1978) Added to the National Registry: 2018 Essay by Rickey Vincent (Guest Post)*

“September”—Earth Wind & Fire (1978) Added to the National Registry: 2018 Essay by Rickey Vincent (guest post)* “Do you remember, the 21st night of September…?” those were the opening lyrics to one of the biggest hits of 1978, and still one of the most entertaining pop songs over the decades. It is a song about memory, memories that have happened, and memories yet to come. A contagious joy emanates from the song, with lyrics that tease with importance, yet captivate with a repeating “ba-de-ya” refrain that is as memorable as any lyrical phrase. The song is a staple of movie soundtracks (such as “Ted 2,” “Barbershop--The Next Cut,” and “Night at the Museum”), commercial jingles, and family gatherings everywhere. With music providing tickles of percussion, soaring yet comforting horn lines, and the breathtaking harmonies, “September” is one of Earth Wind & Fires’ most catchy sing- along favorites. The lyrics spoke of dancing under the stars, and of celebrating moments in our lives. The words captured ideas that seemed so meaningful, yet really were not. The 21st night of September? What date was that? Was it someone’s birthday? How could a song tug at one’s memories, and yet refer to so little? Co-writer Allee Willis has said the date was used simply because it “sounded right when sung.” The irony was that Earth Wind & Fire had had a run of some of the most thought- provoking and inspiring messages in their catalogue of hit songs, from “Keep Your Head To the Sky” to “Shining Star” and “That’s the Way of the World,” there was an expectation of something deeper underpinning the uplifting experience. -

ICLA 2016 – Abstracts General Conference Sessions, July 17Th, 2016

ICLA 2016 – Abstracts General Conference Sessions, July 17th, 2016 ICLA 2016 – Abstracts General Conference Sessions Content Fri, July 22nd, 09:00, Urmil Talwar , C. Many cultures, many idioms ..................................................... 7 Fri, July 22nd, 11:00, Marjanne Gooze, D. The language of thematics ................................................... 8 Fri, July 22nd, 11:00, Marta Teixeira Anacleto, D. The language of thematics ....................................... 9 Fri, July 22nd, 18:00, no chair yet, E. Comparatists at work - professional communication ................ 11 Fri, Huly 22nd, 16:00, no chair yet, C. Many cultures, many idioms ..................................................... 11 Fri, July 22nd, 11:00, no chair yet, D. The language of thematics ......................................................... 12 Fri, July 22nd, 14:00, no chair yet, D. The language of thematics ......................................................... 13 Fri, July 22nd, 09:00, no chair yet , C. Many cultures, many idioms ..................................................... 14 Fri, July 22nd, 11:00, Yiu-wai Chu , C. Many cultures, many idioms ..................................................... 15 Fri, July 22nd, 14:00, Gabriele Eckart, C. Many cultures, many idioms ................................................ 17 Fri, July 22nd, 16:00, Nagla Bedeir, E. Comparatists at work - professional communication ............... 18 Fri, July 22nd, 09:00, no chair yet, D. The language of thematics ........................................................ -

Quelques Livres Abordant La Question Des Migrants, Demandeurs D'asile

Quelques livres abordant la question des migrants, demandeurs d’asile, réfugiés, immigrés et autres exilés ÉTABLIE PAR BERNARD BRETONNIÈRE Bruno Catalano, série Les Voyageurs, v. 2013. REMERCIEMENTS.- Cette approche bibliographique a pu être en partie établie à la faveur de deux résidences d’auteur, la première, pilotée par la Maison de la Poésie de Rennes et Région Bretagne et accompagnée par la DDEC 35, dans la Communauté de communes de la Bretagne romantique (2017), la seconde en Pays de Haute Sarthe (novembre 2018 - mars 2019), à l’initiative du Département de la Sarthe et de la DRAC Pays-de-la-Loire, en partenariat avec les communes de Fresnay-sur-Sarthe et de Sillé-le-Guillaume, et de l’association Festivals en Pays de Haute Sarthe. Que tous leurs responsables, artisans et petites mains, sans oublier les élèves et les enseignants régulièrement rencontrés dans leurs classes, soient remerciés. Les deux thèmes retenus pour ces résidences étaient Les migrations, élargi à la formule « La poésie ne connaît pas de frontières », et Le mouvement. En outre, ces résidences ont permis à l’auteur invité d’avancer dans la rédaction de son « journal-poème-théâtre » Six semaines avec Platon, texte qui rapporte l’expérience d’accueil, dans une famille de l’agglomération nantaise, d’un demandeur d’asile venu de Brazzaville où il était menacé de mort. Dans des versions condensées par rapport au manuscrit intégral, encore en chantier et donc inédit, plus de vingt lectures lectures ont été données, souvent accompagnées par des musiciens. Cette approche bibliographique (qui ne fait pas l’impasse sur les ouvrages d’extrême droite), ici datée du 26/04/2019, est en perpétuelle évolution, s’enrichissant et se corrigeant au fil des informations complémentaires et des parutions nouvelles. -

Blackletter: Fiction and a Wall of Precedent

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Summer 8-2015 Blackletter: Fiction and a Wall of Precedent Louis Anthony Di Leo University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Fiction Commons, Nonfiction Commons, and the Religion Law Commons Recommended Citation Di Leo, Louis Anthony, "Blackletter: Fiction and a Wall of Precedent" (2015). Dissertations. 127. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/127 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi BLACKLETTER: FICTION AND A WALL OF PRECEDENT by Louis Anthony Di Leo Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2015 ABSTRACT BLACKLETTER: FICTION AND A WALL OF PRECEDENT by Louis Anthony Di Leo August 2014 The eight stories that make up Blackletter explore situations in which people are forced to challenge the legitimacy of authority, rethink and rebuild their own identities, or confront their own involvement in human and environmental degradation. A central theme running throughout the collection is law, broadly, and the ways in which people adhere to or sometimes break from a particular rule, be it social or legislative. In each case, the role of law and its correlation to place and identity—either overt or veiled— serves as a major component of each story. -

Feb 18 Customer Order Form

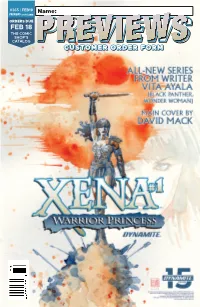

#365 | FEB19 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE FEB 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Feb19 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 1/10/2019 11:11:39 AM SAVE THE DATE! FREE COMICS FOR EVERYONE! Details @ www.freecomicbookday.com /freecomicbook @freecomicbook @freecomicbookday FCBD19_STD_comic size.indd 1 12/6/2018 12:40:26 PM ASCENDER #1 IMAGE COMICS LITTLE GIRLS OGN TP IMAGE COMICS AMERICAN GODS: THE MOMENT OF THE STORM #1 DARK HORSE COMICS SHE COULD FLY: THE LOST PILOT #1 DARK HORSE COMICS SIX DAYS HC DC COMICS/VERTIGO TEEN TITANS: RAVEN TP DC COMICS/DC INK TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA ASCENDER #1 TURTLES #93 STAR TREK: YEAR FIVE #1 IMAGE COMICS IDW PUBLISHING IDW PUBLISHING TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES #93 IDW PUBLISHING THE WAR OF THE REALMS: JOURNEY INTO MYSTERY #1 MARVEL COMICS XENA: WARRIOR PRINCESS #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT FAITHLESS #1 BOOM! STUDIOS SIX DAYS HC DC COMICS/VERTIGO THE WAR OF LITTLE GIRLS THE REALMS: OGN TP JOURNEY INTO IMAGE COMICS MYSTERY #1 MARVEL COMICS TEEN TITANS: RAVEN TP DC COMICS/DC INK AMERICAN GODS: THE MOMENT OF XENA: THE STORM #1 WARRIOR DARK HORSE COMICS PRINCESS #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT STAR TREK: YEAR FIVE #1 IDW PUBLISHING SHE COULD FLY: FAITHLESS #1 THE LOST PILOT #1 BOOM! STUDIOS DARK HORSE COMICS Feb19 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 1/10/2019 3:02:07 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Strangers In Paradise XXV Omnibus SC/HC l ABSTRACT STUDIOS The Replacer GN l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Mary Shelley: Monster Hunter #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Bronze Age Boogie #1 l AHOY COMICS Laurel & Hardy #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Jughead the Hunger vs. -

Soundtrack a Note from Bethany

SOUNDTRACK A NOTE FROM BETHANY I believe romantic comedy is one of the greatest genres ever created. Is there anything funnier than love? (I’ll answer that one for you: No. There is not.) And while I now love reading in the genre and, you know, writing in it, my love for rom-coms was first awakened through movies. Sleepless in Seattle, While You Were Sleeping, The Cutting Edge, When Harry Met Sally . , My Best Friend’s Wedding, Bridget Jones’s Diary, You’ve Got Mail . the list goes on and on. As I was writing Wooing Cadie McCaffrey, I felt pretty satisfied that I was writing a worthy homage to the genre I love so much. But the fact is, rom- com movies have one distinct advantage over rom-com books. (Well, two distinct advantages, if we can just group Colin Firth, Tom Hanks, Hugh Grant, and the rest of them into one joint advantage . .) Movies have the advantage of music. So many rom-com movie moments are inextricably linked to a song that played in the background while the moment was happening and the emotions we felt at the time . The giddiness of seeing Joe Fox deliver daisies to a sick Kathleen Kelly while “Signed, Sealed, Delivered, I’m Yours” provides the soundtrack. The hilarity of watching Rupert Everett serenade Julie Roberts with “I Say a Little Prayer” and with the help of some waiters wearing lobster mitts. The sadness accompanying Hugh Grant as he passes through a year of seasons in Notting Hill with “Ain’t No Sunshine” as his only companion.