Ocular Complications of Mucopolysaccharidoses Juvenile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Article • a Case Series in Optometric Management of Diverse Vertical

Article • A Case Series in Optometric Management of Diverse Vertical Deviations Darah McDaniel-Chandler, OD • Southern College of Optometry Memphis, Tennessee ABSTRACT Background: Vertical deviations present in diverse patient populations with a multitude of puzzling symptoms and complaints. Many patients with vertical deviations have visited numerous doctors looking for an explanation for their symptoms of dizziness, headaches, motion sickness, and double vision. Vertical deviations may be apparent in the clinical optometric exam sequence, but at other times, additional testing must be performed to uncover a vertical heterophoria, including fixation disparity, vertical vergences, a period of diagnostic occlusion, or Maddox rod. Case Report: Three case reports are reviewed with diverse presentations of vertical deviations. The first case report outlines Patient A, a 51-year-old female who presented with dizziness along with a latent hyperphoria that was not apparent on the initial clinical examination. The second case report outlines Patient B, a 52-year-old female who presented with a longstanding large-angle vertical strabismus with strabismic amblyopia in the right eye. The third case report outlines Patient C, a 61-year-old female who presented with intermittent vertical diplopia following a cerebrovascular accident. The three cases all underwent vision therapy or vision therapy in combination with prismatic correction, and all three cases experienced symptom reduction following treatment with optometric vision rehabilitation. Conclusion: -

Neural Correlates of Convergence Eye Movements in Convergence Insufficiency Patients Vs

Neural Correlates of Convergence Eye Movements in Convergence Insufficiency Patients vs. Normal Binocular Vision Controls: An fMRI Study A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Biomedical Engineering by Chirag B. Limbachia B.S.B.M.E., Wright State University, 2014 2015 Wright State University Wright State University GRADUATE SCHOOL January 18, 2016 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPER- VISION BY Chirag B. Limbachia ENTITLED Neural Correlates of Convergence Eye Movements in Convergence Insufficiency Patients vs. Normal Binocular Vision Controls: An fMRI Study BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIRE- MENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Science in Biomedical Engineering. Nasser H. Kashou Thesis Director Jaime E. Ramirez-Vick, Ph.D., Chair, Department of Biomedical, Industrial, and Human Factors Engineering Committee on Final Examination Nasser H. Kashou, Ph.D. Marjean T. Kulp, O.D., M.S., F.A.A.O. Subhashini Ganapathy, Ph.D. Robert E.W. Fyffe, Ph.D. Vice President for Research and Dean of the Graduate School ABSTRACT Limbachia, Chirag. M.S.B.M.E., Department of Biomedical, Industrial, and Human Factor En- gineering, Wright State University, 2015. Neural Correlates of Convergence Eye Movements in Convergence Insufficiency Patients vs. Normal Binocular Vision Controls: An fMRI Study. Convergence Insufficiency is a binocular vision disorder, characterized by reduced abil- ity of performing convergence eye movements. Absence of convergence causes, eye strain, blurred vision, doubled vision, headaches, and difficulty reading due frequent loss of place. These symptoms commonly occur during near work. The purpose of this study was to quantify neural correlates associated with convergence eye movements in convergence in- sufficient (CI) patients vs. -

Care of the Patient with Accommodative and Vergence Dysfunction

OPTOMETRIC CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE Care of the Patient with Accommodative and Vergence Dysfunction OPTOMETRY: THE PRIMARY EYE CARE PROFESSION Doctors of optometry are independent primary health care providers who examine, diagnose, treat, and manage diseases and disorders of the visual system, the eye, and associated structures as well as diagnose related systemic conditions. Optometrists provide more than two-thirds of the primary eye care services in the United States. They are more widely distributed geographically than other eye care providers and are readily accessible for the delivery of eye and vision care services. There are approximately 36,000 full-time-equivalent doctors of optometry currently in practice in the United States. Optometrists practice in more than 6,500 communities across the United States, serving as the sole primary eye care providers in more than 3,500 communities. The mission of the profession of optometry is to fulfill the vision and eye care needs of the public through clinical care, research, and education, all of which enhance the quality of life. OPTOMETRIC CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE CARE OF THE PATIENT WITH ACCOMMODATIVE AND VERGENCE DYSFUNCTION Reference Guide for Clinicians Prepared by the American Optometric Association Consensus Panel on Care of the Patient with Accommodative and Vergence Dysfunction: Jeffrey S. Cooper, M.S., O.D., Principal Author Carole R. Burns, O.D. Susan A. Cotter, O.D. Kent M. Daum, O.D., Ph.D. John R. Griffin, M.S., O.D. Mitchell M. Scheiman, O.D. Revised by: Jeffrey S. Cooper, M.S., O.D. December 2010 Reviewed by the AOA Clinical Guidelines Coordinating Committee: David A. -

The Most Common Causes of Eye Pain at 2 Tertiary Ophthalmology and Neurology Clinics

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2018 The Most Common Causes of Eye Pain at 2 Tertiary Ophthalmology and Neurology Clinics Bowen, Randy C ; Koeppel, Jan N ; Christensen, Chance D ; Snow, Karisa B ; Ma, Junjie ; Katz, Bradley J ; Krauss, Howard R ; Landau, Klara ; Warner, Judith E A ; Crum, Alison V ; Straumann, Dominik ; Digre, Kathleen B Abstract: BACKGROUND Eye pain is a common complaint, but no previous studies have determined the most common causes of this presenting symptom. Our objective was to determine the most com- mon causes of eye pain in 2 ophthalmology and neurology departments at academic medical centers. METHODS This was a retrospective cross-sectional analysis and chart review at the departments of ophthalmology and neurology at the University Hospital Zurich (USZ), University of Zürich, Switzer- land, and the University of Utah (UU), USA. Data were analyzed from January 2012 to December 2013. We included patients aged 18 years or older presenting with eye pain as a major complaint. RESULTS Two thousand six hundred three patient charts met inclusion criteria; 742 were included from USZ and 1,861 were included from UU. Of these, 2,407 had been seen in an ophthalmology clinic and 196 had been seen in a neurology clinic. Inflammatory eye disease (conjunctivitis, blepharitis, keratitis, uveitis, dry eye, chalazion, and scleritis) was the underlying cause of eye pain in 1,801 (69.1%) of all patients analyzed. Although only 71 (3%) of 2,407 patients had migraine diagnosed in an ophthalmology clinic as the cause of eye pain, migraine was the predominant cause of eye pain in the neurology clinics (100/196; 51%). -

Strabismus: a Decision Making Approach

Strabismus A Decision Making Approach Gunter K. von Noorden, M.D. Eugene M. Helveston, M.D. Strabismus: A Decision Making Approach Gunter K. von Noorden, M.D. Emeritus Professor of Ophthalmology and Pediatrics Baylor College of Medicine Houston, Texas Eugene M. Helveston, M.D. Emeritus Professor of Ophthalmology Indiana University School of Medicine Indianapolis, Indiana Published originally in English under the title: Strabismus: A Decision Making Approach. By Gunter K. von Noorden and Eugene M. Helveston Published in 1994 by Mosby-Year Book, Inc., St. Louis, MO Copyright held by Gunter K. von Noorden and Eugene M. Helveston All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission from the authors. Copyright © 2010 Table of Contents Foreword Preface 1.01 Equipment for Examination of the Patient with Strabismus 1.02 History 1.03 Inspection of Patient 1.04 Sequence of Motility Examination 1.05 Does This Baby See? 1.06 Visual Acuity – Methods of Examination 1.07 Visual Acuity Testing in Infants 1.08 Primary versus Secondary Deviation 1.09 Evaluation of Monocular Movements – Ductions 1.10 Evaluation of Binocular Movements – Versions 1.11 Unilaterally Reduced Vision Associated with Orthotropia 1.12 Unilateral Decrease of Visual Acuity Associated with Heterotropia 1.13 Decentered Corneal Light Reflex 1.14 Strabismus – Generic Classification 1.15 Is Latent Strabismus -

17-2021 CAMI Pilot Vision Brochure

Visual Scanning with regular eye examinations and post surgically with phoria results. A pilot who has such a condition could progress considered for medical certification through special issuance with Some images used from The Federal Aviation Administration. monofocal lenses when they meet vision standards without to seeing double (tropia) should they be exposed to hypoxia or a satisfactory adaption period, complete evaluation by an eye Helicopter Flying Handbook. Oklahoma City, Ok: US Department The probability of spotting a potential collision threat complications. Multifocal lenses require a brief waiting certain medications. specialist, satisfactory visual acuity corrected to 20/20 or better by of Transportation; 2012; 13-1. Publication FAA-H-8083. Available increases with the time spent looking outside, but certain period. The visual effects of cataracts can be successfully lenses of no greater power than ±3.5 diopters spherical equivalent, at: https://www.faa.gov/regulations_policies/handbooks_manuals/ techniques may be used to increase the effectiveness of treated with a 90% improvement in visual function for most One prism diopter of hyperphoria, six prism diopters of and by passing an FAA medical flight test (MFT). aviation/helicopter_flying_handbook/. Accessed September 28, 2017. the scan time. Effective scanning is accomplished with a patients. Regardless of vision correction to 20/20, cataracts esophoria, and six prism diopters of exophoria represent series of short, regularly-spaced eye movements that bring pose a significant risk to flight safety. FAA phoria (deviation of the eye) standards that may not be A Word about Contact Lenses successive areas of the sky into the central visual field. Each exceeded. -

Nonspecific Orbital Inflammation (Idiopathic; Associated with Systemic Inflammatory Syndrome/Autoimmune Disease)

Ophthalmology Grand Rounds Christopher Adam, M.D. (PGY2) August 6, 2015 Case Presentation • 39 y/o BF who presented to UHB-ED with c/o painless right upper and lower eyelid swelling x 2 days. History • Pertinent positives (+): multiple past episodes of eyelid swelling which resolved with steroids. • Pertinent negatives (-): denied decreased vision, pain, diplopia, trauma, discharge, insect bites, HA, fevers, weight loss, arthralgias/myalgias, rash. History • PMH: SLE (Dx 2008), Anemia, Sickle cell trait. • POH: multiple past episodes of eyelid swelling. • PSH: LEEP, Myomectomy. • Meds: Prednisone and Ciprofloxacin (started by Rheum PTA), Bosentan, Omeprazole, Vitamin D. Previously on Hydroxychloroquine. • All: NKDA. • SH: no use of tobacco products, alcohol, or illicit drugs. • FH: no glaucoma, blindness, auto-immune disease. Exam Findings • NVasc: 20/20- OD, 20/20 OS • Pupils: 5-3mm err OU, no APD • EOMs: full OU; no pain/diplopia/limitations • CVF: ftfc OU • Tpen: 13/13 Slit Lamp Exam • L/L/A: +right upper/lower eyelid edema with thickened SQ tissue. +warmth/erythema. +Focal point tenderness of superior trochlea region on deep palpation of right orbit. • C/S: w/q OU. • Cornea: clear OU. • A/C: d/q OU. • Iris/Pupils: rr OU. • Lens: clear OU. Dilated Fundus Exam • Vitreous: clear OU. • C/D: 0.4, s/p OU. • Macula: flat OU. • V/P: normal caliber, no heme/holes/tears OU. Axial CT w/o contrast showing soft tissue thickening of the right preseptal region and orbital fat standing (arrow). Thickening of the MR insertion. Absence of sinus disease. Axial CT w/o contrast showing right SO and trochlea hyperdensity (arrow). -

Etiology of Heterophoria and Heterotropia

CHAPTER 9 Etiology of Heterophoria and Heterotropia n heterophoria there is a relative deviation of Factors Responsible for the Ithe visual axes held in check by the fusion Manifestation of a Deviation mechanism, whereas in heterotropia there is a manifest deviation of the visual axes. The relative Abnormalities of Fusion Mechanism position of the visual axes is determined by the equilibrium or disequilibrium of forces that keep DEFECT OF MOTOR FUSION IN INFANTILE ES- the eyes properly aligned and of forces that disrupt OTROPIA. Motor fusion in patients with hetero- this alignment. Clearly, the fusion mechanism and phoria is adequate to maintain a proper alignment its anomalies are involved in some manner in of the eyes. This does not mean that patients with producing comitant heterotropias. To understand a heterophoria necessarily have normal sensory the etiology of neuromuscular anomalies of the fusion. In those with higher degrees of heteropho- eyes, therefore, one should also gain an insight ria, suppression and a high stereoscopic threshold into other factors that determine the relative posi- may be present, but motor responses are sufficient tion of the visual axes. to keep the eyes aligned. In heterotropia this is First, there are anatomical factors, which con- not the case. These circumstances have led to a sist of orientation, size, and shape of the orbits; theory of the etiology of strabismus developed by size and shape of the globes; volume and viscosity Worth in 1903 in his famous book on squint.156 of the retrobulbar tissue; functioning of the eye His theory was that the essential cause of squint muscles as determined by their insertion, length, is a defect of the fusion faculty156, p. -

Persistent Strabismus After Cataract Extraction

Број 9 ВОЈНОСАНИТЕТСКИ ПРЕГЛЕД Страна 689 UDC: 617.741−004.1−089.168.1−06 CASE REPORT Persistent strabismus after cataract extraction Mirjana P. Dujić*, Katarina R. Misailović*, Milena M. Kovačević† Clinical Center Zvezdara, *Department of Ophthalmology, †Center of Anesthesiology and Reanimation, Belgrade Background. Transient ocular misalignment as a complication of parabulbar and peribul- bar anesthesia has already been reported in the literature. The aim of our study was to pre- sent a case of irreversible iatrogenic vertical strabismus after cataract surgery, which had to be operated on. Methods. Clinical and orthoptic evaluation of a female patient with ver- tical diplopia after phacoemulsification cataract surgery. Results. One week after the un- eventful surgery, a 68-year-old patient complained of a sudden vertical deviation in the op- erated eye. The patient had not had a history of previous motility disorders. On examina- tion, the patient showed hypertropia in the left eye of 15−20 degrees in primary position. Three and 6 months postoperatively, there was no a spontaneous improvement, while the persistent vertical deviation was 40 prism dioptres. Strabismus surgery was required 1 year after the cataract surgery. Conclusion. Diplopia is a complication of peribulbar an- esthesia which could be persistent. The superior and inferior rectus muscle are especially vulnerable. Its occurrence may be technique - related and the incidence increases when hyaluronidase is not available. K e y w o r d s : cataract extraction; diplopia; anesthesia, local; enzymes; strabismus; iatrogenic disease. Introduction the clinic during a 2-year-period when hyaluronidase was not available. Diplopia is an infrequent, but well-known complica- A 68-year-old woman had uneventful phacoemulsifi- tion after cataract surgery (1, 2) Postoperative misalignment cation cataract surgery with a posterior chamber intraocular may result from many mechanisms, some of which are the lens (PCIOL) implantation in the left eye. -

GAZE and AUTONOMIC INNERVATION DISORDERS Eye64 (1)

GAZE AND AUTONOMIC INNERVATION DISORDERS Eye64 (1) Gaze and Autonomic Innervation Disorders Last updated: May 9, 2019 PUPILLARY SYNDROMES ......................................................................................................................... 1 ANISOCORIA .......................................................................................................................................... 1 Benign / Non-neurologic Anisocoria ............................................................................................... 1 Ocular Parasympathetic Syndrome, Preganglionic .......................................................................... 1 Ocular Parasympathetic Syndrome, Postganglionic ........................................................................ 2 Horner Syndrome ............................................................................................................................. 2 Etiology of Horner syndrome ................................................................................................ 2 Localizing Tests .................................................................................................................... 2 Diagnosis ............................................................................................................................... 3 Flow diagram for workup of anisocoria ........................................................................................... 3 LIGHT-NEAR DISSOCIATION ................................................................................................................. -

Download This PDF File

S Afr Optom 2006 65 (4) 150 − 156 A retrospective analysis of heterophoria values in a clinical population aged 18 to 30 y e a r s NT Makgaba* Department of Optometry, University of Limpopo, Turfloop campus, P. Bag X1106, Sovenga, 0727 South Africa <[email protected]> Abstract with a mean of 0.08 pd right hypophoria (SD Information on heterophoria values in South = ± 0.96). The distributions of heterophoria Africans is scanty. The purpose of this paper at distance and near were non-normal. There therefore, is to present information on the dis- was no significant gender variation in the tribution of heterophoria in a clinical popula- horizontal values for distance vision and the tion aged 18 to 30 years, which hitherto is not vertical (distance and near) ones. However, available. The data presented here was obtained there was a statistically significant gender varia- from the record cards of 475 black South tion in the near horizontal values (p > 0.05). African patients examined at the Optometry There was no significant variation in hetero- clinic, University of Limpopo (Turfloop cam- phoria values with age. The data presented pus) between 2000 and 2005. The patients were here will be useful for comparison with simi- examined by final year students under the super- lar data from South Africa or other countries. vision of qualified optometrists. Heterophoria was measured for each patient using the von Keywords: Heterophoria, horizontal pho- Graefe method. The horizontal heterophoria ria, vertical phoria, esophoria, exophoria. for distance vision (6 m) ranged from 16 prism diopters (pd) esophoria to 12 pd exophoria with a mean of 0.74 pd exophoria (SD = ± 2.84 pd). -

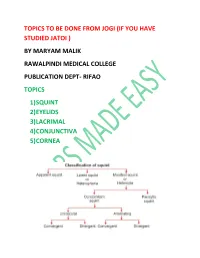

Topics to Be Done from Jogi (If You Have

TOPICS TO BE DONE FROM JOGI (IF YOU HAVE STUDIED JATOI ) BY MARYAM MALIK RAWALPINDI MEDICAL COLLEGE PUBLICATION DEPT- RIFAO TOPICS 1) SQUINT 2) EYELIDS 3) LACRIMAL 4) CONJUNCTIVA 5) CORNEA LATENT SQUINT (HETEROPHORIA) Types Esophoria—There is a tendency for deviation of the eyeball inwards. Exophoria—There is a tendency for deviation of the eyeball outwards. Hyperphoria—There is a tendency for deviation of the eyeball upwards. Cyclophoria—There is a torsional deviation of the eye. Anisophoria—The deviation of the eyeball varies with the direction of gaze. Orthophoria—There is no deviation of the eyes even when the fusion is broken Etiology 1. Increased requirement for accommodation and convergence as in hypermetropia results in esophoria. 2. Decreased requirement for accommodation and convergence as in myopia results in exophoria. 3. Occupations requiring too much close work such as goldsmith, watchmakers. 4. General poor health, fatigue and advancing age. 1. Cover Test Principle Fusion of the two eyes is abolished by covering one eye. Method The patient looks at a distant object. • While observing one eye, cover and uncover the other eye. The movements of the observed eye and the eye under cover are noted. • Repeat this process with the other eye and then alternately. Interpretation 1. If there is no movement, patient has orthophoria. 2. If there is inwards movement on removing the cover the patient has exophoria. 3. If there is outwards movement on removing the cover the patient has esophoria. 2. Maddox Rod Test Principle This test is done to find out heterophoria for distance. It alters the appearance of the retinal image in one eye.