Negotiating Civic Space in Belfast Or the Tricolour: Here Today, Gone Tomorrow’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Belfast Waterfront / Ulster Hall

Appendix B Ulster Hall - Programming Policy 1. Introduction The Ulster Hall will reopen in March 2009 following a major refurbishment. This is the second phase of the refurbishment work (Phase I 2005-06) and will see major changes to the venue including: Ulster Orchestra taking residency in the venue Addition of interpretive displays Launch of an education and community outreach programme Opportunity for the venue to actively programme and promote a range of events. Since 2004 the venue has been managed alongside Belfast Waterfront and it is envisaged that existing expertise within the Waterfront staff structure will inform and direct the relaunch of the Ulster Hall. This document addressed the programming policy for the ‘new’ Ulster Hall, identifying the changes in the venue’s operation and management and taking into account the overall marketplace in which the venue operates. 2. Context This policy is based on the following assumptions about how the Ulster Hall will operate in the future: A receiving house and programming venue Programming will have a mix of commercial and developmental objectives Opportunity for business use of the venue will be exploited In-house PA and lighting facilities will be available Premises will be licensed – alcohol consumption permitted in the main space for standing concerts An improved environment – front of house facilities, seating, dressing rooms Hire charges will need to be set appropriately to reflect these changes in order to compete within the market, whilst acknowledging a previously loyal client base 90683 - 1 - 3. Historical and Current Position Historical Position Typically the Ulster Hall has hosted around 150 events each year. -

Statement of Community Involvement

AD001 Belfast Planning Service Statement of Community Involvement Revised March 2018 1 Keeping in Touch You can contact the Council’s Planning Service in the following ways:- In writing to: Planning Service, Belfast City Council, Cecil Ward Building, 4-10 Linenhall Street, Belfast, BT2 8BP By email: [email protected] By telephone: 02890 500 510 Textphone: 028 9054 0642 Should you require a copy of this Statement of Community Involvement in an alternative format, it can be made available on request in large print, audio format, DAISY or Braille and may be made available in minority languages to meet the needs of those for whom English is not their first language. Keeping you informed The Planning and Place Department has set up a database of persons/stakeholders with an interest in the Local Development Plan. Should you wish to have your details added to this database please contact the Team on any of the ways listed above. 2 AD001 Contents 1.0 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 5 2.0 What is the Statement of Community Involvement? .................................................................5 3.0 The Preparation of the Local Development Plan .......................................................................7 4.0 The Council’s Development Management Function .................................................................19 5.0 Community Involvement in Planning Enforcement ..................................................................24 -

The Road to War

1912-1923 Reflecting on a decade of War and Revolution in Ireland 1914: the Road to War Keynote speakers Professor Thomas Otte, Professor of Diplomatic History, University of East Anglia Professor Keith Jeffery, Professor of British History, Queen’s University Belfast Belfast City Hall, Belfast 9.30-5.00 Saturday 14 June 2014 1912-1923 Reflecting on a decade of War and Revolution in Ireland 1914: the Road to War PROGRAMME Second Panel Session: Ireland on the eve of the war Saturday 14th June Dr Catriona Pennell, Senior Lecturer in History, Belfast City Hall University of Exeter - Ireland/UK at outbreak of war 9.30 am Registration Prof Richard Grayson, Head of History (2011-14) and Professor of Twentieth Century 10.00 am Official opening and introduction: History, Goldsmiths, University of London - Social Dr Michael Murphy, President, background of Dublin/Belfast volunteers University College Cork and Chair, Universities Ireland 3.15 pm Refreshments Welcome: Councillor Maire Hendron, 3.35 pm History Ireland Hedge School: Deputy Lord Mayor of Belfast Mr Tommy Graham, Editor, History Ireland Dr Colin Reid, Senior Lecturer in History, 10.30 am Chair: Professor Eunan O’Halpin, Professor of Northumbria University, Newcastle – Irish Contemporary Irish History, Trinity College Dublin Volunteers Keynote address: Professor Thomas Otte, Dr Timothy Bowman, Senior Lecturer in History, Professor of Diplomatic History, University of University of Kent - Ulster Volunteers East Anglia - July 1914: Reflections on an Dr Margaret Ward, Visiting Fellow in -

Committee Application Development Management Report Application ID: LA04/2015/1492/F Date of Committee: 17 April 2018 Proposal

Committee Application Development Management Report Application ID: LA04/2015/1492/F Date of Committee: 17 April 2018 Proposal: Location: Proposed residential development comprising Land adjacent to McKinney House of 5No townhouses and 13No apartments with Musgrave Park associated car parking and landscaping Malone Lower Belfast BT9 7HZ Referral Route: Proposal is for more than 12 residential units with objection Recommendation: Approval Subject to Conditions Applicant Name and Address: Agent Name and Address: Windsor Developments Ltd Coogan & Co Architects Ltd No 6 Saintfield Road 144 Upper Lisburn Road Lisburn Finaghy BT27 5BD Belfast BT10 0BG Executive Summary: Full planning permission is sought for a residential development comprising 5No townhouses and 13No apartments with associated car parking and landscaping. The proposal comprises a central four storey apartment block fronting onto Musgrave Park, flanked on each side by two and a half storey townhouses (two to the south and three to the north). A further two apartment blocks, each two storeys in height, are proposed to the rear of the site. A total of 28 car parking spaces are proposed centrally within the site, accessed by way of an arched opening which punctuates the four storey apartment block at ground floor. The site is unzoned land within the development limits as designated in the BUAP 2001 and it is zoned as an uncommitted housing site (SB04/10) in draft BMAP 2015. There is a history of applications for apartment development at the site, one previous refusal and two previous planning approvals although now expired are still a material consideration. 4 letters of objection have been received (including 2 letters from Belfast Trust) raising issues including: Potential for overlooking, proximity to and potential for overshadowing to Forest Lodge, increase in traffic generation and over development / out of character. -

3 Day Itinerary: Belfast

3 Day Itinerary: Belfast TITANIC BELFAST BELFAST BELFAST CITY HALL Day 1 Day 3 Arrive Belfast Airport. Meet your chauffer at the airport. He will bring Free day in Belfast. you to the hotel. Once checked in, you will go to the Titanic Belfast Experience. Day 4 Titanic Belfast Experience. Private transfer to Belfast Airport A self-guided experience through 9 state of the art interactive Where to stay in Belfast? galleries detailing the entire Titanic story in chronological order. • The Merchant Hotel – 5 Star (Please allow at least 1hr 45 mins). The five star Merchant Hotel is a harmonious blend of Victorian Titanic Belfast is a visitor attraction and a monument to Belfast’s splendour and Art Deco inspired sleek modernity, situated in the maritime heritage on the site of the former Harland & Wolff shipyard historic Cathedral Quarter of Belfast’s city centre. in the city’s Titanic Quarter where the RMS Titanic was built. It • The Fitzwilliam Hotel Belfast – 4 Star tells the stories of the ill-fated Titanic, which hit an iceberg and It’s an enviable location, and the hotel impresses from the outset sank during her maiden voyage in 1912, and her sister ships RMS with its friendly concierge (valet parking) and the understatedly Olympic and HMHS Britannic. The building contains more than sumptuous foyer. Designed to look and feel like a (very classy) 12,000 square metres (130,000 sq ft) of floor space, most of living-room, it has an aura of calmness and serenity, with which is occupied by a series of galleries etc. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Belfast Waterfront and Ulster Hall Ltd Shareholders' Committee, 17/05/2021 17:15

Public Document Pack Democratic Services Section Legal and Civic Services Department Belfast City Council City Hall Belfast BT1 5GS 11th May, 2021 MEETING OF THE MEMBERS OF THE BELFAST WATERFRONT AND ULSTER HALL LTD SHAREHOLDERS’ COMMITTEE Dear Alderman/Councillor, A meeting of the Members of the Belfast Waterfront and Ulster Hall Ltd Shareholders’ Committee will meet remotely via Microsoft Teams on Monday, 17th May, 2021 at 5.15 pm, for the transaction of the business noted below. You are requested to attend. Yours faithfully, SUZANNE WYLIE Chief Executive AGENDA: 1. Routine Matters (a) Apologies (b) Minutes (Pages 1 - 6) (c) Declarations of Interest 2. Restricted Items (a) Performance Report - Quarter 4, 2020/21 (Pages 7 - 22) (b) Draft Business Plan 2021/22 (to follow) (c) Capital and Maintenance Update (Pages 23 - 26) (d) Update on Casual Workers (Pages 27 - 28) (e) Governance of BWUH (Pages 29 - 34) - 2 - Agenda Item 1b Belfast Waterfront and Ulster Hall Ltd. Shareholders’ Committee Thursday, 4th March, 2021 MEETING OF BELFAST WATERFRONT AND ULSTER HALL LTD. SHAREHOLDERS’ COMMITTEE HELD REMOTELY VIA MICROSOFT TEAMS Members present: Alderman Haire (Chairperson); Alderman Copeland; Councillors Canavan, Matt Collins, Flynn, M. Kelly, Kyle, Magee, McAteer and McCabe. In attendance: Ms. J. Corkey, Chief Executive, ICC Belfast (Belfast Waterfront and Ulster Hall Ltd.); Mr. I. Bell, Director of Finance and Systems, ICC Belfast (Belfast Waterfront and Ulster Hall Ltd.); Mr. J. Greer, Director of Economic Development; Ms. S. Grimes, Director of Physical Programmes; Mrs. S. Steele, Democratic Services Officer; and Mrs. L. McLornan, Democratic Services Officer. Apologies Apologies for inability to attend were reported from Councillors Cobain, Mulholland and Newton. -

Belfast a Port for Everyone

Belfast | 1 Titanic Slipways Belfast A port for everyone Belfast is a city with a unique character and history that sets it apart from other cruise destinations. Since the first cruise ship arrival in 1996, Belfast has seen unprecedented growth in both cruise calls and visitor numbers. We combine our heritage with a legendary welcome and a sense of humour, which ensures cruise visitors enjoy their stay with us. An award-winning cruise destination, Belfast is now widely regarded as one of the UK and Ireland’s most vibrant and exciting city destinations, full of unique visitor attractions and friendly faces. There is so much for visitors to explore in the incredible city whose innovation, passion and pride gave birth to RMS Titanic and many other great ships. From castles towering high above the lough to tranquil canal towpaths by beautiful parks, Belfast has a myriad of wonderful experiences to enthrall visitors. From just two cruise calls in 1996 to 148 calls in 2019 with 285,000 cruise visitors, Belfast is now the third most popular destination in the UK and Ireland for one-day cruise ship calls after Dublin and Orkney. It’s against this backdrop that Belfast Harbour opened the island’s first dedicated cruise terminal in May 2019 Belfast Harbour has invested more than £500,000 to upgrade the quayside, which now includes a Visitor Information Centre managed by our partners, Visit Belfast. Staffed by Visit Belfast’s travel advisors the new terminal utilises the latest digital and audio-visual technology to showcase Belfast and Northern Belfast | 2 Ireland’s visitor attractions. -

'Peoi·Le's Democr3.Cy' at Belfast City Hall on L'j Th

S~ches m'~ ' i e :it m8~~in? of 'PeoI·le's Democr3.cy' at Belfast City Hall on W '- ::l.e~"lJ." L'J th :=IGto'uer, 1965, commencing at J.O p.m. - -..- ----~ , -'-''--'-'-'-- V.. 're f,<:Hd to-d':! y to decl~re that we're not g,fraid of anything, even the 1'>1. in , 'l..'1d we'll stay iWl'e to give our message (Cheers from crowd). rie will stay htl re to o: ]..,e our !!leSS9.g9 to tne people of Bel fast and also to these people over ilere (Cheers traro ~ro71d) who have been persuaded by the sectarianism of this CO"!L'flu'1i toY not to take part in this parade, but we'll persuade them, we'll persuade everybody else in Horthern Ireland that our cause is just and dese;fVes ~upport (Cheers from crowd). r~'a is meeting has been called by the 'People's Democracy', I would hope that this meeting would be carried out in the way that meetings of the 'rl:lOple 's Democracy' are oarried out. we will have various speakers he l'€ to-day \'Jho,lill t'llk on the question principally of Civil i :~j.,'h ts :md the quest ion 0:' the 'L-eople' s Democracy'. I would ask one of the or ~:J niStHS 'l.Ild one of thp. committee of ten, tlr. Boyle, to address the aurii.::ncs t th~k you. MeRJ>e-"J!'Si 'j F the '?eople 's De ,llO cracy' can you hear me! Members of the 'lsopIe's OOr:.o cracy' this is a very important event in our movement,at long last we have re1chea the City Hall (Cheers from orowd), at long last we have m3rchec. -

Code of Conduct for Belfast City Council Employees

CODE OF CONDUCT FOR BELFAST CITY COUNCIL EMPLOYEES CODE OF CONDUCT FOR BELFAST CITY COUNCIL EMPLOYEES CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Status of the Code 2.0 FRAMEWORK FOR THE CODE 2.1 National Agreement on Pay and Conditions of Service 2.2 Principles of Conduct 3.0 CONSULTATION AND IMPLEMENTATION 4.0 MODEL CODE OF CONDUCT FOR LOCAL GOVERNMENT EMPLOYEES 4.1 Standards of Behaviour, Impartiality and Conflicts of Interest 4.2 Disclosure of Information 4.3 Political Neutrality 4.4 Potential Conflict of Interest Situations 4.5 Appointments and Other Employment Matters 4.6 Outside Commitments 4.7 Personal Interests 4.8 Equality Issues 4.9 Separation of Roles During Procurement 4.10 Fraud and Corruption 4.11 Use of Financial Resources 4.12 Hospitality and Gifts 4.13 Sponsorship - Giving and Receiving 4.14 Whistleblowing 4.15 Breaches of the Code of Conduct APPENDICES Appendix 1 LEGAL AND OTHER PROVISIONS RELATING TO THE CODE OF CONDUCT KEY TERMS USED IN THE CODE OF CONDUCT Appendix 2 DOE – LGPD1 Cover Letter re. Local Government Employee and Councillor Working Relationship Protocol LOCAL GOVERNMENT EMPLOYEE & COUNCILLOR WORKING RELATIONSHIP PROTOCOL (Issued October 2014) CODE OF CONDUCT FOR BELFAST CITY COUNCIL EMPLOYEES 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Status of the Code Under Article 35(1)(b) of the Local Government (Miscellaneous Provisions) (NI) Order 1992, the functions of the Local Government Staff Commission include: “establishing and issuing a code of recommended practice as regards conduct of officers of councils”. A Code of Conduct for Local Government Officers was therefore issued as a statutory recommendation for implementation in district councils in Northern Ireland. -

Cave Hill Country Park and Belfast Castle Leaflets

24030 makeup 24/9/06 4:11 pm Page 20 24030 makeup 24/9/06 4:11 pm Page 21 CaveCave Hill CountryHill Country Park Park Route description* Trail 07 This route climbs up the Cave Hill over unsurfaced paths and gives breathtaking views over Belfast. History Distance There are many signs from 4.5 miles 7.2 km. the past illustrating man’s long association with Cave Hill. These include a stone Average Time cairn on the summit; a 2 hrs 30 mins. – 3 hrs. crannog or lake dwelling (now part of the zoo); several Access raths and ringforts; McArt’s By bus - Belfast Castle and Hazelwood entrance; fort and Belfast Castle. Metro Services: 1A-1H (Mon-Sat) 1C-1E, 1H (Sun), The Belfast Castle Estate Carr’s Glen; 12, 61. was donated to Belfast by the Donegall family. Various By car - Car parking at Belfast Castle, Belfast Zoo parcels of land were acquired by Belfast City (Hazelwood), Upper Cavehill Road, and Upper Council to make up Cave Trail Route Hightown Road. Hill Country Park. This is a challenging circular route beginning at Belfast Castle and following the green waymarking arrows. Go down the footpath a short way and take the path to Devil’s Punchbowl (3) HoweverTrail it can Routebe joined from Bellevue car park, Upper ContinuingThingsthe left. Climb of on, Interest over take the ridgethe nextand descend path on into your Belfast left. A local name for this steep-sided depression in the ground. Hightown road or Upper Cavehill road. Castle Estate. Return to the starting point by means of WoodlandThis skirts (1) round Planted the towards edge of theCaves Devil’s (4) It is not knownCaves for(4) Punchbowlthe footpath up(3) the, passes main driveway. -

Flags EQIA Final Decision Report Appendices

Policy on the Flying of the Union Flag Equality Impact Assessment – Final Decision Report Appendices Contents Page Appendix A: Background information 4 A1 Designated Flag Days 5 A2 Further information on the City Hall, Ulster Hall and 6 Duncrue Complex A3 Policies of Belfast City Council 8 A4 Policies of the NI Executive 9 A5 Advice by the Equality Commission 11 A6 Policies of other authorities 12 Appendix B: Available data 15 B1 Belfast City Residents (by Section 75 category) 16 B2 Belfast City Council Employees (by community 19 background and gender) Appendix C: Research gathered in 2003 21 C1 Complaints and comments (summary) 22 C2 Opinion of Senior Counsel (summary) 23 C3 Submissions by party groups (summary) 25 C4 Opinions expressed by the Equality Commission 28 (summary) C5 Results of surveys of employees and suppliers 29 (summary) Appendix D: Research gathered in 2011-12 31 D1 Complaints and comments (summary) 32 D2 Opinion of Senior Counsel 34 D3 Submissions by party groups 53 (a) Alliance Party 53 (b) Progressive Unionist Party 54 (c) Democratic Unionist Party 54 (d) Social Democratic and Labour Party 55 (e) Sinn Féin (including legal advice sought) 63 D4 Opinions expressed by the Equality Commission 72 D5 Opinions expressed by the Human Rights Commission 77 (summary) D6 View of the Council’s Consultative Forum 79 D7 Results of survey of visitors to the City Hall 80 2 Appendix E: Consultation responses 84 E1 Equality Commission 85 E2 Community Relations Council 88 E3 Consular Association of Northern Ireland 91 E4 Responses from -

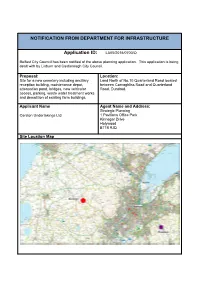

NOTIFICATION from DEPARTMENT for INFRASTRUCTURE Application ID

NOTIFICATION FROM DEPARTMENT FOR INFRASTRUCTURE Application ID: LA05/2016/0700/O Belfast City Council has been notified of the above planning application. This application is being dealt with by Lisburn and Castlereagh City Council. Proposal: Location: Site for a new cemetery including ancillary Land North of No.10 Quarterland Road located reception building, maintenance depot, between Carnaghliss Road and Quarterland attenuation pond, bridges, new vehicular Road, Dundrod. access, parking, waste water treatment works and demolition of existing farm buildings. Applicant Name Agent Name and Address: Strategic Planning Carston Undertakings Ltd 1 Pavilions Office Park Kinnegar Drive Holywood BT18 9JQ Site Location Map Background Full details of the planning application (drawings, reports and the Environmental Statement) can be accessed of the planning portal at http://epicpublic.planningni.gov.uk. Draft Response: Belfast City Council has no specific planning comments in relation to the merits of the submitted application. We would however like to provide some contextual information in respect of the projected need and demand for burial provision. As the Burial Board for Belfast, Belfast City Council’s current position is that we have limited burial capacity and the only new burial space has been developed at Roselawn, which lies outside the Council’s boundary to the East. To ensure that we have sufficient provision and in locations that serve all the residents of the city we have been searching for new burials lands since the 1990s. An extension to Roselawn Cemetery in the late 2000s provided the Council with a short to medium term solution but it has not been possible to secure new burial land to provide the Council with a longer term solution.