Bennett, Michael (1943-1987) by Bud Coleman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Silent Auction List

September 22, 2019 ………………...... 10 am - 10:30 am S-1 2018 Broadway Flea Market & Grand Auction poster, signed by Ariana DeBose, Jay Armstrong Johnson, Chita Rivera and others S-2 True West opening night Playbill, signed by Paul Dano, Ethan Hawk and the company S-3 Jigsaw puzzle completed by Euan Morton backstage at Hamilton during performances, signed by Euan Morton S-4 "So Big/So Small" musical phrase from Dear Evan Hansen , handwritten and signed by Rachel Bay Jones, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul S-5 Mean Girls poster, signed by Erika Henningsen, Taylor Louderman, Ashley Park, Kate Rockwell, Barrett Wilbert Weed and the original company S-6 Williamstown Theatre Festival 1987 season poster, signed by Harry Groener, Christopher Reeve, Ann Reinking and others S-7 Love! Valour! Compassion! poster, signed by Stephen Bogardus, John Glover, John Benjamin Hickey, Nathan Lane, Joe Mantello, Terrence McNally and the company S-8 One-of-a-kind The Phantom of the Opera mask from the 30th anniversary celebration with the Council of Fashion Designers of America, designed by Christian Roth S-9 The Waverly Gallery Playbill, signed by Joan Allen, Michael Cera, Lucas Hedges, Elaine May and the company S-10 Pretty Woman poster, signed by Samantha Barks, Jason Danieley, Andy Karl, Orfeh and the company S-11 Rug used in the set of Aladdin , 103"x72" (1 of 3) Disney Theatricals requires the winner sign a release at checkout S-12 "Copacabana" musical phrase, handwritten and signed by Barry Manilow 10:30 am - 11 am S-13 2018 Red Bucket Follies poster and DVD, -

“Kiss Today Goodbye, and Point Me Toward Tomorrow”

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Missouri: MOspace “KISS TODAY GOODBYE, AND POINT ME TOWARD TOMORROW”: REVIVING THE TIME-BOUND MUSICAL, 1968-1975 A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School At the University of Missouri In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By BRYAN M. VANDEVENDER Dr. Cheryl Black, Dissertation Supervisor July 2014 © Copyright by Bryan M. Vandevender 2014 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled “KISS TODAY GOODBYE, AND POINT ME TOWARD TOMORROW”: REVIVING THE TIME-BOUND MUSICAL, 1968-1975 Presented by Bryan M. Vandevender A candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Dr. Cheryl Black Dr. David Crespy Dr. Suzanne Burgoyne Dr. Judith Sebesta ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I incurred several debts while working to complete my doctoral program and this dissertation. I would like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to several individuals who helped me along the way. In addition to serving as my dissertation advisor, Dr. Cheryl Black has been a selfless mentor to me for five years. I am deeply grateful to have been her student and collaborator. Dr. Judith Sebesta nurtured my interest in musical theatre scholarship in the early days of my doctoral program and continued to encourage my work from far away Texas. Her graduate course in American Musical Theatre History sparked the idea for this project, and our many conversations over the past six years helped it to take shape. -

Audience Insights Table of Contents

GOODSPEED MUSICALS AUDIENCE INSIGHTS TABLE OF CONTENTS JUNE 29 - SEPT 8, 2018 THE GOODSPEED Production History.................................................................................................................................................................................3 Synopsis.......................................................................................................................................................................................................4 Characters......................................................................................................................................................................................................5 Meet the Writer........................................................................................................................................................................................6 Meet the Creative Team.......................................................................................................................................................................7 Director's Vision......................................................................................................................................................................................8 The Kids Company of Oliver!............................................................................................................................................................10 Dickens and the Poor..........................................................................................................................................................................11 -

Program Notes

“Come on along, you can’t go wrong Kicking the clouds away!” Broadway was booming in the 1920s with the energy of youth and new ideas roaring across the nation. In New York City, immigrants such as George Gershwin were infusing American music with their own indigenous traditions. The melting pot was cooking up a completely new sound and jazz was a key ingredient. At the time, radio and the phonograph weren’t widely available; sheet music and live performances remained the popular ways to enjoy the latest hits. In fact, New York City’s Tin Pan Alley was overflowing with "song pluggers" like George Gershwin who demonstrated new tunes to promote the sale of sheet music. George and his brother Ira Gershwin composed music and lyrics for the 1927 Broadway musical Funny Face. It was the second musical they had written as a vehicle for Fred and Adele Astaire. As such, Funny Face enabled the tap-dancing duo to feature new and well-loved routines. During a number entitled “High Hat,” Fred sported evening clothes and a top hat while tapping in front of an enormous male chorus. The image of Fred during that song became iconic and versions of the routine appeared in later years. The unforgettable score featured such gems as “’S Wonderful,” “My One And Only,” “He Loves and She Loves,” and “The Babbitt and the Bromide.” The plot concerned a girl named Frankie (Adele Astaire), who persuaded her boyfriend Peter (Allen Kearns) to help retrieve her stolen diary from Jimmie Reeve (Fred Astaire). However, Peter pilfered a piece of jewelry and a wild chase ensued. -

TRU Speak Program 021821 XS

THEATER RESOURCES UNLIMITED VIRTUAL BENEFIT PLAYBILL TRU SPEAK Hear Our Voices! An evening of awareness to benefit THEATER RESOURCES UNLIMITED executive producer Bob Ost associate producers Iben Cenholt and Joe Nelms benefit chair Sanford Silverberg plays produced by Jonathan Hogue, Stephanie Pope Lofgren, James Rocco, Claudia Zahn assistant to the producers Maureen Condon technical coordinator Iben Cenholt/RuneFilms editor-technologists Iben Cenholt/RuneFilms, Andrea Lynn Green, Carley Santori, Henry Garrou/Whitetree, LLC video editors Sam Berland/Play It Again Sam’s Video Productions, Joe Nelms art direction & graphics Gary Hughes casting by Jamibeth Margolis Casting Social Media Coordinator Jeslie Pineda featuring MAGGIE BAIRD • BRENDAN BRADLEY • BRENDA BRAXTON JIM BROCHU • NICK CEARLEY • ROBERT CUCCIOLI • ANDREA LYNN GREEN ANN HARADA • DICKIE HEARTS • CADY HUFFMAN • CRYSTAL KELLOGG WILL MADER • LAUREN MOLINA • JANA ROBBINS • REGINA TAYLOR CRYSTAL TIGNEY • TATIANA WECHSLER with Robert Batiste, Jianzi Colon-Soto, Gha'il Rhodes Benjamin, Adante Carter, Tyrone Hall, Shariff Sinclair, Taiya, and Stephanie Pope Lofgren as the Voice of TRU special appearances by JERRY MITCHELL • BAAYORK LEE • JAMES MORGAN • JILL PAICE TONYA PINKINS •DOMINIQUE SHARPTON • RON SIMONS HALEY SWINDAL • CHERYL WIESENFELD TRUSpeak VIP After Party hosted by Write Act Repertory TRUSpeak VIP After Party production and tech John Lant, Tamra Pica, Iben Cenholt, Jennifer Stewart, Emily Pierce Virtual Happy Hour an online musical by Richard Castle & Matthew Levine directed -

Student Guide Table of Contents

GOODSPEED MUSICALS STUDENT GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS APRIL 13 - JUNE 21, 2018 THE GOODSPEED Production History.................................................................................................................................................................................3 Synopsis.......................................................................................................................................................................................................4 Characters......................................................................................................................................................................................................5 Meet the Writers.....................................................................................................................................................................................6 Meet the Creative Team........................................................................................................................................................................8 Presents for Mrs. Rogers......................................................................................................................................................................9 Will Rogers..............................................................................................................................................................................................11 Wiley Post, Aviation Marvel..............................................................................................................................................................16 -

Cast Biographies Chris Mann

CAST BIOGRAPHIES CHRIS MANN (The Phantom) rose to fame as Christina Aguilera’s finalist on NBC’s The Voice. Since then, his debut album, Roads, hit #1 on Billboard's Heatseekers Chart and he starred in his own PBS television special: A Mann For All Seasons. Chris has performed with the National Symphony for President Obama, at Christmas in Rockefeller Center and headlined his own symphony tour across the country. From Wichita, KS, Mann holds a Vocal Performance degree from Vanderbilt University and is honored to join this cast in his dream role. Love to the fam, friends and Laura. TV: Ellen, Today, Conan, Jay Leno, Glee. ChrisMannMusic.com. Twitter: @iamchrismann Facebook.com/ChrisMannMusic KATIE TRAVIS (Christine Daaé) is honored to be a member of this company in a role she has always dreamed of playing. Previous theater credits: The Most Happy Fella (Rosabella), Titanic (Kate McGowan), The Mikado (Yum- Yum), Jekyll and Hyde (Emma Carew), Wonderful Town (Eileen Sherwood). She recently performed the role of Cosette in Les Misérables at the St. Louis MUNY alongside Norm Lewis and Hugh Panero. Katie is a recent winner of the Lys Symonette award for her performance at the 2014 Lotte Lenya Competition. Thanks to her family, friends, The Mine and Tara Rubin Casting. katietravis.com STORM LINEBERGER (Raoul, Vicomte de Chagny) is honored to be joining this new spectacular production of The Phantom of the Opera. His favorite credits include: Lyric Theatre of Oklahoma: Disney’s The Little Mermaid (Prince Eric), Les Misérables (Feuilly). New London Barn Playhouse: Les Misérables (Enjolras), Singin’ in the Rain (Roscoe Dexter), The Music Man (Jacey Squires, Quartet), The Student Prince (Karl Franz u/s). -

Resume 2017.Pgs

JANE LABANZ www.janelabanz.com Height: 5’5” / Weight: 120 212 300 5653 Soprano/Mix/Light Belt AEA SAG/AFTRA Strong High Notes 330 West 42nd Street, 18th Floor New York, NY 10036 212-629-9112 [email protected] BROADWAY/NATIONAL TOURS Director Anything Goes Hope u/s (Broadway and National Tour) Jerry Zaks The King and I Anna (Sandy Duncan / Stefanie Powers standby) Baayork Lee The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas Ginger (Doatsey Mae u/s) Thommie Walsh (Cast album, w/ Ann-Margret) Eric Schaeffer Annie Grace Farrell Bob Fitch 42nd Street Phyllis Dale (Peggy u/s) Mark Bramble The Sound of Music (w/ Marie Osmond) Swing/Dance Captain Jamie Hammerstein Bye Bye Birdie (w/ Tommy Tune/Anne Reinking) Kim u/s (to Susan Egan) Gene Saks Dr. Dolittle (w/ Tommy Tune) Puddleby Tommy Tune Cats Jelly/Jenny/Swing David Taylor REGIONAL THEATRE Tuck Everlasting (World Premiere /Alliance Theatre) Older Winnie (Nanna u/s) Casey Nicholaw (Dir.) Love Story (American Premiere) Alison Barrett Walnut Street Theatre A Little Night Music Mrs. Nordstrom / Dance Captain Cincinnati Playhouse 9 to 5 Violet Newstead Tent Theatre I Love a Piano Eileen Milwaukee Repertory Always…Patsy Cline Louise Seger New Harmony Theatre The Cocoanuts (Helen Hayes Award, Best Musical) Polly Potter Arena Stage Noises Off Brooke Ashton Totem Pole Playhouse Cinderella Fairy Godmother / Queen u/s North Shore Music Theatre The Nerd Clelia Waldgrave Totem Pole Playhouse The Music Man Marian Paroo Pittsburgh Playhouse George M! Nellie Cohan Theatre by the Sea George M! Agnes Nolan (plus 9 other -

Rachel Chavkin Takes on Broadway

Arts & Humanities High Art, High Ideals: Rachel Chavkin Takes on Broadway The Tony Award-winning director of Hadestown may be theater’s most forward- thinking artist. By Stuart Miller '90JRN | Fall 2019 Zack DeZon / Getty Images Making her way to the stage of Radio City Music Hall to accept the 2019 Tony Award for best direction of a musical, Rachel Chavkin ’08SOA was thinking about time. She had all of ninety seconds to get to the microphone and deliver her speech, which was written on a much-creased piece of paper folded in her hands. Seven months pregnant, Chavkin, thirty-eight, was not about to sprint. As she told Columbia Magazine days later, “I warned my husband: if they call my name, I won’t have time to hug you!” Hadestown, an enthralling, profoundly moving retelling of the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, would, by night’s end, capture eight awards, including best original score and best musical. The accolades were not only hard won — Chavkin, a leading light of experimental theater, and Anaïs Mitchell, a singer-songwriter from Vermont, shaped and refined Hadestown for seven years — but also, some might say, overdue. In seventy-three years of the Tony Awards (named after Antoinette Perry, an actress, director, and theater advocate), Chavkin became just the fourth woman to win for best direction of a musical, joining Julie Taymor (The Lion King), Susan Stroman (The Producers), and Diane Paulus ’97SOA (Pippin). And in 2019, out of twelve new musicals on Broadway, Hadestown was the only one directed by a woman. The show, playing at the Walter Kerr Theatre on West 48th Street, is set mostly in a New Orleans–style barrelhouse at a time of economic and environmental decay. -

A CHORUS LINE Teaching Resource.Pages

2016-2017 SEASON 2016-2017 SEASON Teacher Resource Guide and Lesson Plan Activities Featuring general information about our production along with some creative activities to Tickets: thalian.org help you make connections to your classroom curriculum before and after the show. 910-251-1788 The production and accompanying activities address North Carolina Essential Standards in Theatre or Arts, Goal A.1: Analyze literary texts & performances. CAC box office 910-341-7860 Look for this symbol for other curriculum connections. A Chorus Line Book, Music & Lyrics by: Jim Jacobs and Warren Casey April 28th - May 7th 7:30 PM Friday - Saturday and 3:00 PM Sunday Hannah Block Historic USO / Community Arts Center Second Street Stage 120 South 2nd Street (Corner of Orange) About this Teaching Resource Resource This Teaching Resource is designed to help build new partnerships that employ theatre and the arts. A major theme that runs through A Chorus Line, is the importance of education and Summary: the influence of teachers in the performers’ lives. In the 2006 Broadway production of A Page 2 Chorus Line, it was stated that the cast had spent, all together, 472 years in dance training with Summary, 637 teachers! The gypsies in A Chorus Line, are judged and graded, just as students are About the Musical, every day. Students know what it’s like to be “on the line.” This study guide for A Chorus Line, explores the Pulitzer Prize winning show in an interdisciplinary curriculum that takes in Vocabulary English/Language Arts, History/Social Studies, Music, Theatre, and Dance. Learning about Page 3 how A Chorus Line, was created will make viewing the show a richer experience for young Gypsies, Writing Prompts, people. -

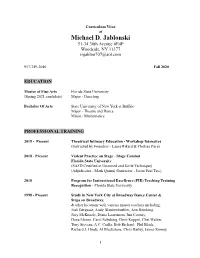

Michael Jablonski's CV

Curriculum Vitae of Michael D. Jablonski 51-34 30th Avenue #E4P Woodside, NY 11377 [email protected] 917-749-2040 Fall 2020 EDUCATION Master of Fine Arts Florida State University (Spring 2021 candidate) Major - Directing Bachelor Of Arts State University of New York at Buffalo Major - Theatre and Dance Minor - Mathematics PROFESSIONAL TRAINING 2019 - Present Theatrical Intimacy Education - Workshop Intensives (Instructed by Founders - Laura Rikard & Chelsea Pace) 2018 - Present Violent Practice on Stage - Stage Combat Florida State University (SAFD Certified in Unarmed and Knife Technique) (Adjudicator - Mark Quinn) (Instructor - Jason Paul Tate) 2018 Program for Instructional Excellence (PIE) Teaching Training Recognition - Florida State University 1998 - Present Study in New York City at Broadway Dance Center & Steps on Broadway, & other locations with various master teachers including: Josh Bergasse, Andy Blankenbuehler, Ann Reinking, Joey McKneely, Diana Laurenson, Jim Cooney, Dana Moore, Carol Schuberg, Dorit Koppel, Chet Walker, Tony Stevens, A.C. Ciulla, Bob Richard, Phil Black, Richard J. Hinds, Al Blackstone, Chris Bailey, James Kinney 1 2010 - Present One on One Studio - New York City On Camera Workshops (Selection by Audition) Instructors - Bob Krakower & Marci Phillips EMPLOYMENT HISTORY 2020 - 2021 Fall & Spring Florida State University, Florida Instructor In The School of Theatre (Intro to Music Theatre Dance - New Course Developed) (Instructor of Record - Michael D. Jablonski) (Culminations - Senior Seminar Course) (Instructor - Michael D. Jablonski) 2019 - 2020 Fall & Spring Florida State University, Florida Instructor In The School of Theatre (Intro to Music Theatre Dance - New Course Developed) (Instructor of Record - Michael D. Jablonski) Graduate Teaching Assistant (Performance I - Uta Hagen Acting Class) (Instructor of Record - Chari Arespacochaga) (Performance I Lab - Uta Hagen Workshop class) (Instructor of Record - Michael D. -

The Inventory of the Kevin Kelly Collection #1038

The Inventory of the Kevin Kelly Collection #1038 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Kelly, Kevin (1934-1994) Gift of Charles M. Wirth March 1995 OUTLINE OF INVENTORY 7 Paige Boxes, 7 packages I. Manuscripts II. Files III. Correspondence IV. Tape Recordings V. Publicity Photographs VI. Printed 2 Kelly, Kevin (1934-1994) Gift of Charles M. Wirth March, 1995 Box 1 I. Manuscripts A. Student Papers, 1949-1954 1. "Cretins, Coffin-Worms and Cruelty", February, 1949 2, "The Creator and the Creation", Dec. 1, 1949 3. "Occupational Survey Dramatic Critic: "The Night Life of the Gods", 1949 4. "Modern Tragedy" AA Thesis (B.U.) March 31, 1950 5. "Critiques and Essays in Criticism, Selected by Robert Wooster Stallman" May 1, 1951 6. "We Who are Without Kings; Aeschylus and Eugene O'Neill" Jan 11, 1953 7. "Certain Critical Theories on Shakespeare's The Tempest, 1900-1953. Prof. Wagenknecht's Seminar. Jan 13, 1954. 2 versions 8. Undated. "A Well-Rotted Ship; Critical Theories on the Tempest" 9. Undated. "Another Time Another Place" 10. Undated: Outline for history of the theater 11. Undated: "The Temper of the Theater" Preface Sp. B. Novel GYPSIES, JUGGLERS AND CLOWNS Outline lp. Typscript pl-40. C. Scripts by Others 1. CAKEWALK by Peter Feibleman. Mimeo lllp. Draft 10/6/92, Rewrite 4/8/93 2. GRAPES OF WRATH Adapted and Directed by Frank Galat, Steppenwolf Theatre, 1989. mimeo 116p. 3, SOME AMERICANS ABROAD by Richard Nelson. October, 1989. Mimeo, 71p. 3 Box 2 II. FILES as set up by KK. containing drafts of articles, clips, letters, ect.