© 2012 Anahi Russo ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Power of the Voice: Listening to Mexican and Central American Immigrant Experiences (1997-2010)

The Power of the Voice: Listening to Mexican and Central American Immigrant Experiences (1997-2010) BY Megan L. Thornton Submitted to the Department of Spanish and Portuguese and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________________________ Dr. Jill S. Kuhnheim, Chairperson ______________________________ Dr. Vicky Unruh ______________________________ Dr. Yajaira Padilla ______________________________ Dr. Stuart Day ______________________________ Dr. Ketty Wong Date Defended: _________________ ii The Dissertation Committee for Megan L. Thornton certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Power of the Voice: Listening to Mexican and Central American Immigrant Experiences (1997-2010) Committee: ______________________________ Dr. Jill S. Kuhnheim, Chairperson ______________________________ Dr. Vicky Unruh ______________________________ Dr. Yajaira Padilla ______________________________ Dr. Stuart Day ______________________________ Dr. Ketty Wong Date Defended: _________________ iii Abstract Megan L. Thornton, Ph.D. Department of Spanish and Portuguese, April 2010 University of Kansas This dissertation examines representations of immigrant experiences in Mexican and Central American cultural texts at the end of the twentieth and beginning of the twenty-first centuries. By examining immigrant experiences through the lenses of testimonial writing, fictional narrative, documentary film, and popular music, this -

Canciller Meade Conversa Con Raúl Castro En Cumbre

Regresa al Auditorio El IMSS y los penales lideran Luismi para hacer historia: quejas ante 223 shows en total >31 la CNDH >14 $5$ PESOS Jueves 29 de enero de 2015 DIARIOAñoA IX No. 2538 IMAGEN [email protected] México Peña Nieto: Sólo se hizo la consignación por homicidio, dice Murillo Karam Se gastan 61 mil mdp en atender las Abierta, la investigación adicciones El presidente Enrique Peña Nieto convocó a todos los niveles de gobierno y a la sociedad a formar sobre el caso Iguala: PGR un frente común para revertir la amenaza de las “La verdad histórica es que los 43 normalistas GURJDV$ÀUPy que México ha fueron asesinados, incinerados y arrojados al río” empeñado su... >15 Por José Luis Montañez de la PGR precisó que con abierta”. Murillo Karam El dato la presentación del martes dijo que entre los asuntos A partir de la La investigación por la “lo que hice fue consignar pendientes en el caso está próxima semana desaparición, homicidio por homicidio, no podía el “cumplimiento de las todos los e incineración de los 43 ser de otra manera… órdenes de aprehensión y derechohabientes normalistas de Ayotzinapa pero la investigación no la integración de averigua- del Infonavit con no está cerrada, reiteró el ha terminado y dije que ciones que se ingresos menores a 5 procurador general Jesús no había terminado la van a acumular INSISTE JESÚS MURILLO KARAM mil 467 pesos al mes, Murillo Karam. El titular averiguación, que estaba a las que ya... >13 en que no hubo participación de militares en los hechos. -

Lisboa Región Porto Y Norte

Cine Lisboa Región DocLisboa Lisbon & Sintra Film Festival Fecha de inicio: 2021-10-21 Fecha final: 2021-10-31 Fecha de inicio: 2021-11-11 Fecha final: 2021-11-20 Website: http://www.doclisboa.org Website: http://www.leffest.com Contactos: Lisboa - Culturgest, Cinema São Jorge, Contactos: Lisboa, Sintra Cinemateca Portuguesa e Cinema Ideal El Lisbon & Sintra Film Festival celebra el cine como En octubre, el mundo entero cabe en Lisboa. creación artística, destacando especialmente su transversalidad y la fascinación que ejerce sobre las otras Este es el lema de DocLisboa, un festival que invita a pensar artes. en el documental, con sus implicaciones y potencial. Presenta el cine como una práctica que permite encontrar Con ese leitmotiv, apuesta por la exploración del séptimo arte nuevos modos de pensar y de actuar en el mundo, asumiendo de exaltando las tres vertientes específicas del cine, es decir, el este modo una libertad que supone una implicación íntima entre arte, el ocio y la industria, a través de la obra de los más lo artístico y lo político. inefables realizadores contemporáneos. El festival DocLisboa intenta mostrar obras que, eventualmente, Sin embargo, el Lisbon & Sintra Film Festival constituye nos ayuden a comprender el mundo en que vivimos y a asimismo un desafío, basado en convertir la región de Lisboa encontrar en él posibles fuerzas del cambio. en un punto de encuentro anual indispensable para quienes opinan que el cine no solo es entretenimiento, fascinación, ensoñación y glamour, sino también un motivo de reflexión, creación, intercambio y, sobre todo, placer. Madeira Funchal Madeira Nature Film Festival Fecha de inicio: 2021-10-07 Fecha final: 2021-10-10 Contactos: Reid's Belmond Palace Hotel, Teatro Municipal Baltazar Dias - Funchal Asista al Madeira Nature Film Festival que promete despertar las conciencias ante la preservación ecológica de los recursos naturales. -

DIARIOIMAGEN QUINTANAROO Miércoles 26 De Agosto De 2015

Fauna a salvo Luis Miguel regresa al con máquina Auditorio Nacional en noviembre; especial para recolectar el inicia venta de boletos >21 sargazo >5 $5 PESOS Miércoles 26 de agosto de 2015 DIARIOAño 4 No. 1112 IMAGEN [email protected] Quintana Roo Modernización Listos, juzgados penales orales En la película Entrenando a mi papá de Quintana Roo Playa del Carmen.- En sólo ocho meses Solida- Mauricio Islas ridad cuenta ya con los Juzgados Penales Orales, que se suman a la moder- nización del Poder Judicial regresará al en Quintana Roo, donde se invirtieron más de 12 millones de >12 pesos... Atlante a la El dato La crisis económica y la devaluación del primera división peso propició >23 que en el primer semestre de este año se registrara un crecimiento del negocio prendario, en 30 por ciento >3 Protestas por tarifa única HOY ESCRIBEN Yolanda Montalvo >2 Jorge Cupul >6 Ruth Sansores >3 Roberto Vizcaíno >9 Ramón Zurita Sahagún >11 IMPUNIDAD Augusto Corro >8 Francisco Rodríguez >13 Víctor Sánchez Baños >10 Ángel Soriano >11 Mauricio Conde >15 Emilio Carrasco >26 DE AGUAKAN Gloria Carpio >21 La empresa de Cancún cobra hasta el aire que Victoria G. Prado >16 pasa por los medidores, denuncia Javier Arzápalo >3 diarioimagenqroo.mx 2 Opinión DIARIOIMAGEN QUINTANAROO Miércoles 26 de agosto de 2015 Derecho de réplica “Sospechosismo” sobre POR YOLANDA MONTALVO el “quintanarroísmo” Como pólvora, ayer corrió en blancos dientes, pues nació en Lo que quedó claro es que el gobierno del estado, ni el de los nocer que en el distrito 01 de las redes las respectivas CURP el DF el 18 de diciembre de edil de Playa del Carmen tiene diputados, el que se cambiará Aguascalientes se tendrá que de los aspirantes del Partido 1976 y registrado en Chetumal un amigo en el Tribunal Supe- para que coincida con las elec- repetir la elección, tanto el par- Revolucionario Institucional a el siguiente año, ¡aaahhh, pi- rior de Justicia del Estado; no ciones federales será la de pre- tido del colibrí como el PT po- la candidatura al gobierno del llín!, con que defeño. -

Qo Ho Ed 120719 Web-M

AÑO 24 | NÚM. 1161 < WWW.QUEONDAMAGAZINE.COM > 07 DE DIC - 13 DE DC | 2019 FREE! ¡GRATIS! LUIS MIGUEL EL SOL DE MÉXICO 07 DE DICIEMBRE - 13 DE DICIEMBRE | 2019 2 WWW.QUEONDAMAGAZINE.COM In loving memory of Mr. José G. Esparza APRENDE MÁS. HAZ MÁS. COMPARTE MÁS. FOUNDED BY: José G. Esparza And Lilia S. Esparza /1993/ INTERNET ESSENTIALSSM DE COMCAST PO BOX 1805 INTERNET DE ALTA VELOCIDAD ECONÓMICO CYPRESS TEXAS 77410 Phone: (713)880-1133 Internet Essentials te da acceso a Internet de alta velocidad económico. Podrías calificar Fax: (713)880-2322 si tienes al menos un niño elegible para el Programa Nacional de Almuerzos Escolares, recibes asistencia para viviendas públicas o HUD, o eres un veterano con bajos recursos económicos que recibe asistencia federal y/o estatal. PUBLISHERS GABRIEL ESPARZA SIN CONTRATO [email protected] SIN REVISIÓN DE CRÉDITO $ 95 SIN CARGO POR INSTALACIÓN PUBLIC RELATIONS WiFi PARA EL HOGAR INCLUIDO al mes + impuestos ACCESO A HOTSPOTS DE AMANDA G. ESPARZA XFINITY WiFi FUERA DEL [email protected] HOGAR, EN 40 SESIONES 9 DE 1 HORA CADA 30 DÍAS SPORTS EDITOR MICHAEL A. ESPARZA michaele@queondamagazine .com SOLICÍTALO AHORA es.InternetEssentials.com FOTOGRAPH 1-855-SOLO-995 VICTOR LOPEZ Se aplican restricciones. No está disponible en todas las áreas. Limitado al servicio de Internet Essentials para nuevos clientes residenciales que cumplan con ciertos requisitos de elegibilidad. El precio anunciado se aplica a una sola conexión. Las velocidades reales pueden variar y no están garantizadas. Tras la participación inicial Los contenidos periodísticos que se incluyen en este en el programa de Internet Essentials, si se determina que un cliente ya no es elegible para el programa y elige un servicio de Xfinity Internet diferente, se aplicarán las tarifas regulares al servicio de Internet seleccionado. -

El Paso Scene USER's GUIDE

MAR. • • • • •Y o• u•r •m • o•n •t h•l y• g• u•i d• e• t•o • c•o •m •m • u•n •it y• • • • • entertainment, recreation & culture Take a Spring Break Page 23 Art Museum Director headed for Tampa Page 35 Mark Medoff directs new play Page 37 Dwight Yoakum in Mescalero Page 39 Inside: Over 600 things to do, places to see On the cover: ‘On the Way to Carlos & Mickey’s’ by Rami Scully MARCH 2015 www.epscene.com The Marketplace at PLACITA SANTA FE In the n of the Upper Valley 5034 Doniphan 585-9296 10-5 Tues.-Sat. 12:30-4:30 Sun. Antiques Rustics Home Decor Featured artist for March Fine Art Tamara Michalina Collectibles of Tamajesy Roar Pottery Art Sale & Demonstrations Florals March 28-29 STAINED GLASS Saturday: Bead Crocheting Sunday: Needle Felting Linens Jewelry Jewelry designer Tamara Michalina works in all varieties of beads and other materials to make unique creations. Folk Art Her work will be for sale March 28-29, along with kits to make your own! She wearables also will give demonstrations both days. & More Information: www.tamajesyroar.com • (915) 274-6517 MAGIC BISTRO Indoor/Outdoor Dining Antique Lunch 11 am-2:30 pm Tues.-Sun. Traders 5034 Doniphan Dinner 5-10 pm Fri.-Sat. 5034 Doniphan Ste B Live Music! 833-2121 833-9929 Every Friday 6:30 pm - 9:30 pm magicbistroelp.com Ten Rooms of Every Saturday facebook.com/magicbistro Hidden Treasure A Browser’s Paradise! 11:00 am - 2:00 pm • 6:30 pm - 9:30 pm Antiques Collectibles Vintage Clothing Painted Furniture Hats ~ Jewelry Linens ~ Primitives Vintage Toys Nostalgia of Catering • Private Parties All Kinds Page 2 El Paso Scene March 2015 Andress Band Car Show — Andress High attending. -

D2 Resume 2020

DAVID DAVIDIAN 75 NORTH BLUFF CREEK CIRCLE HOUSTON, TEXAS U.S.A. 77382 281-465-0840 HOME 281-465-0841 FAX 818-262-0994 CELLULAR E-MAIL : [email protected] [email protected] JOB SKILLS: Lighting Designer, Video Director, Production Manager, Tour Manager, Stage Manager, and Production Designer I can also combine any two of these positions if that is required. OBJECTIVES: As a Designer/Director: To design and execute the most visually creative, challenging, and cost effective show. I do this in complete collaboration with the Artist, Management, and Production staff. I combine original ideas with proven production methods to create a unique and original production for every client. As a Management Representative: To organize and co-ordinate any production effectively and efficiently. I can organize all the logistical and promotional elements, as well as the day-to-day production aspects of any tour or special event. This means working hand in hand with the management and creative staff to keep costs down, and the creativity and efficiency of the design implementation seamlessly with the highest quality as possible. EXPERIENCE: I have been in the touring music and special events industry for over 25 years. I have worked in every circumstance and venue imaginable, from clubs, to arenas, to stadiums, in the USA and all over the world. I have many years experience with Concert Touring, Special Events, and Corporate Productions. RECENT EMPLOYMENT: TOUR MANAGER: ALICE COOPER FEB 2018 – Present: I worked with the Alice Cooper team on hotels, flights, visas, financials, and day to day logistics for this show around the world. -

Sábado 31 De Enero De 2015 | San Luis Potosí, San Luis Potosí | Año 3 No

Síguenos: www.planoinformativo.com | www.planodeportivo.com | www.quetalvirtual.com Sábado 31 de enero de 2015 | San Luis Potosí, San Luis Potosí | Año 3 No. 759 | Una producción más de Grupo Plano Informativo Locales Entrevista con el Lic. Gustavo Barrera López. Carreras un candidato Fernando Díaz de León Cardona Plano Informativo de calidad y seguro onversar, intercambiar ideas y pun- tegrar los organismos electorales perciben que hoy por hoy los órganos electorales tos de vista con un personaje como sueldos insultantes y, aquél espíritu de se han convertido en oficinas burocráti- CGustavo Barrera López, siempre re- ciudadanizar a las instituciones electora- cas, que han perdido la esencia y el espí- sulta atractivo por la amplitud de sus cono- les, alentado éste por los movimientos so- ritu para el cual fueron creados. Tema por cimientos. La profundidad y claridad con la ciales de la década de los 90 se perdió. Si de mas importantísimo justo en medio de que aborda los temas despierta un interés bien es cierto que San Luis Potosí se colo- un proceso electoral que San Luis Poto- inusual que invita al debate y a la reflexión. có a la vanguardia, ésta sana intención se sí tendrá el próximo 7 de junio, ¿Cual es la Hablar con el reconocido y prestigiado abo- perdió cuando llegó al poder el ex gober- visión que tiene un experto como tú; del gado sobre la historia y el desarrollo políti- nador Horacio Sánchez Unzueta. abogado reconocido en materia electoral, co de la entidad, y en particular de los as- Para Gustavo Barrera, el ejercicio de entre otras ramas como lo es el derecho pectos electorales de actualidad resulta ponderación que realizó el PRI para selec- público el derecho privado? ¿Que espera- inevitable por su vasta experiencia lograda cionar a su candidato al gobierno del esta- mos los ciudadanos a partir de la confor- a los largo de toda una trayectoria en la vi- do fue un ejercicio inteligente que muchos mación de un nuevo organismo electoral da política y social de San Luis Potosí. -

Plantea Aureoles Reducir El Salario De Diputados En

Techos de locales /XLV0LJXHOFRQÀUPD están a punto de ser El Rey del derrumbarse en Auditorio > mercado >5 $5$5 PESOS 3\ULZKLMLIYLYVKL DIARIO(|V5V( IMAGEN KPHYPVPTHNLUXYVV'NTHPSJVTK Quintana Roo /VTVSVNHJP}U 3HWVISHJP}UWYLÄLYLLSHTI\SHU[HQLJVTVM\LU[LKLPUNYLZVZ Nuevo horario UVHMLJ[}SHZ operaciones Se dispara comercio en aeropuerto Cancún.- El vocero de Aeropuertos del Sureste (ASUR), Eduardo Rivade- informal en Cancún QH\UDDÀUPyTXHODHQWUD- da en vigor del nuevo huso El auge de bazares y tianguis afecta la economía del horario en Quin- tana Roo, que sector formal que sí paga impuestos, señala la Canaco lo homologa... >6 Por Ruth Sansores padrón que personas que llevaron a la población a El dato trabajan, más de la mitad optar por el ambulantaje La promoción Cancún.- El comercio in- SUHÀHUHHODPEXODQWDMH(O y los bazares y tianguis, de “Cancún y formal en Cancún registra desempleo, los elevados que les permiten tener una Tesoros del un preocupante crecimien- impuestos, y las ventas forma de trabajo segura, Caribe” en to, que afecta directamente casi nulas en los comer- con una ganancia directa. España atraerá los bolsillos y la economía cios, según la Canaco, El efecto que más visitantes del sector que sí paga Secretaría del Trabajo y trae consigo el PROLIFERAN EN CANCÚN LOS BAZARES Y TIANGUIS, europeos a la impuestos. Del total del Previsión Social e Inegi, ambulantaje... >6 se quejan comerciantes organizados. Isla de Holbox >7 HOY ESCRIBEN Anuncian la Yolanda Montalvo >2 construcción Ruth Sansores >5 Mauricio Conde Olivares >14 del Hospital de Emilio Carrasco >7 Especialidades Roberto Vizcaíno >4 Ramón Zurita Sahagún >5 *OL[\THS(ÄULZKLSWYLZLU[L TLZJVTLUaHYmSHJVUZ[Y\JJP}U Alejo Sánchez Cano >15 KLS/VZWP[HSKL,ZWLJPHSPKHKLZ Víctor Sánchez Baños >10 JVU<UPKHKKL6UJVSVNxHKVUKL ZLPU]LY[PYmUTPSSVULZKL Augusto Corro >3 WLZVZ`ZL\IPJHYmH\UJVZ[HKV KLSH<UPKHKKL,ZWLJPHSPKHKLZ Dante Limón >20 4tKPJHZWHYH+L[LJJP}U` Gloria Carpio >21 +PHNU}Z[PJVKLS*mUJLYKL4HTH LUSHJHYYL[LYH*OL[\THS)HJHSHY Victoria G. -

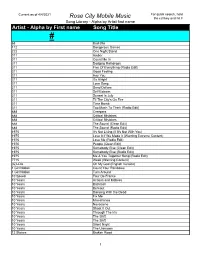

Alpha by First Name Song Title

Current as of 4/4/2021 For quick search, hold Rose City Mobile Music the ctrl key and hit F Song Library - Alpha by Artist first name Artist - Alpha by First name Song Title # 68 Bad Bite 112 Dangerous Games 222 One Night Stand 311 Amber 311 Count Me In 311 Dodging Raindrops 311 Five Of Everything (Radio Edit) 311 Good Feeling 311 Hey You 311 It's Alright 311 Love Song 311 Sand Dollars 311 Self Esteem 311 Sunset In July 311 Til The City's On Fire 311 Time Bomb 311 Too Much To Think (Radio Edit) 888 Creepers 888 Critical Mistakes 888 Critical Mistakes 888 The Sound (Clean Edit) 888 The Sound (Radio Edit) 1975 It's Not Living (If It's Not With You) 1975 Love It If We Made It (Warning Extreme Content) 1975 Love Me (Radio Edit) 1975 People (Clean Edit) 1975 Somebody Else (Clean Edit) 1975 Somebody Else (Radio Edit) 1975 Me & You Together Song (Radio Edit) 7715 Week (Warning Content) (G)I-Dle Oh My God (English Version) 1 Girl Nation Count Your Rainbows 1 Girl Nation Turn Around 10 Speed Tour De France 10 Years Actions and Motives 10 Years Backlash 10 Years Burnout 10 Years Dancing With the Dead 10 Years Fix Me 10 Years Miscellanea 10 Years Novacaine 10 Years Shoot It Out 10 Years Through The Iris 10 Years The Shift 10 Years The Shift 10 Years Silent Night 10 Years The Unknown 12 Stones Broken Road 1 Current as of 4/4/2021 For quick search, hold Rose City Mobile Music the ctrl key and hit F Song Library - Alpha by Artist first name Artist - Alpha by First name Song Title 12 Stones Bulletproof 12 Stones Psycho 12 Stones We Are One 16 Frames Back Again 16 Second Stare Ballad of Billy Rose 16 Second Stare Bonnie and Clyde 16 Second Stare Gasoline 16 Second Stare The Grinch (Radio Edit ) 1975. -

Meter a Duarte Jáquez a La Cárcel Le Ganaría a Peña

Visita EPN Luis Miguel regresa al exposiciones Auditorio Nacional en noviembre; de Miguel Ángel inicia venta de boletos >31 y Da Vinci >15 $5 PESOS Miércoles 26 de agosto de 2015 DIARIOAño IX No. 2684 IMAGEN [email protected] México Gasto operativo Al descubierto, saqueo en Naucalpan Pide INE 15 mil mdp para 2016 Padre y hermano del El Instituto Nacional Electoral (INE) solicitará a la Cámara de Diputados un presupuesto de 15 mil 473.8 millones de pesos para el próximo ex edil, en el desfalco año. En confe- rencia, luego... >13 El fraude por 60 mdp a OAPAS, sólo una de las El dato irregularidades en la gestión de David Sánchez La procuradora general de la Por Dante Limón las saqueadas arcas de ese al padre y hermano de David República, municipio. El peculado podría Sánchez, diputado electo Arely Gómez, El presunto peculado por 60 “no tener la menor importan- preso en Almoloyita: Alberto consideró ayer que la piratería no es un millones de pesos al OAPAS cia”, porque las auditorías han Sánchez y José Sánchez, res- asunto menor, pues este de Naucalpan sería sólo una detectado millonarios desfal- pectivamente. Se han descu- año el sector industrial tercera parte del botín: Entre cos o transas o robos o hurtos bierto, por ejemplo, compras registra pérdidas de 13 más le rasca, más pestilente por adquisiciones simuladas o simuladas de uniformes para mil millones de pesos pus encuentra el Organismo FRPSUDVDFRVWRVLQÁDGRVTXH la policía, refaccio- por la venta de Superior de Fiscalización dejaron millonarias ganancias, nes, artículos para HAN DETECTADO MILLONARIOS HURTOS productos pirata >11 del Estado de México en tanto a ex funcionarios, como RÀFLQDV >12 en adquisiciones en la gestión de David Sánchez. -

José Luis Montañez Aguilar

Operativo El tenor Javier Camarena contra robos encabezará Pasión por la Ópera en Metro; 18 en el Auditorio Nacional >31 detenidos >8 $10$ PESOS Lunes 17 de octubre de 2016 DIARIOIMAGEN Año XI No. 2976 México [email protected] Artesanales Eruviel Ávila Villegas Ladrilleras inaugura juzgados empeoran especializados para aire en Valle agilizar la entrega de México de escrituras Producir ladrillos de mane- ra artesanal es una activi- Ecatepec, Méx.- El gobernador dad que desde hace años Eruviel Ávila Villegas inauguró brinda empleo a los Juzgados Especializados en miles de familias Usucapión de Ecatepec y Xonacatlán, mexicanas... >4 en donde se llevarán a cabo juicios sociales para que los ciudadanos El dato puedan obtener más rápido las escrituras de sus propiedades, La ampliación de siempre y cuando no sean mayores 14.2 kilómetros a 200 metros cuadrados o su valor de la Autopista comercial no rebase los 407 México-Puebla, mil 760 pesos. con una inversión >2 superior a los 2 mil 300 mdp, potenciará el desarrollo comercial y urbano Atrapado por robo de auto en Azcapotzalco de la zona oriente del Valle de México >5 HOY ESCRIBEN Cae en la capital uno de José Luis Montañez >13 Roberto Vizcaíno >7 Ramón Zurita >6 Víctor Sánchez Baños >10 los asesinos de 2 curas Francisco Rodríguez >15 Augusto Corro >3 Los sacerdotes Alejo Nabor Jiménez y José Alfredo Juárez Ángel Soriano >8 fueron levantados y ejecutados en Veracruz en septiembre J. A. López Sosa >11 Por José Luis Montañez sacerdotes en Veracruz. La estaba a bordo de su vehícu- Jorg Palacios >9 ÀVFDOFHQWUDOGH,QYHVWLJDFLyQ lo, estacionado en la avenida Gloria Carpio >31 Elementos de la Procuraduría para la Atención del Delito de Azcapotzalco casi esquina General de Justicia de la Ciu- Robo de Vehículos y Trans- con la calle 5 de Febrero, en Victoria G.