English GCSE Reform from Whitehall to the Classroom: Reform, Resistance, Reality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information Sharing Agreement

OFFICIAL INFORMATION SHARING AGREEMENT BETWEEN NORFOLK CONSTABULARY, NORFOLK COUNTY COUNCIL, NORFOLK SCHOOLS, ACADEMIES, AND COLLEGES UNDER OPERATION ENCOMPASS 1 OFFICIAL Summary Sheet ISA Reference ISA-003453-18 Purpose Operation Encompass is a multi-agency approach to give early notification to schools, academies and colleges that a child or young person has been present, witnessed or been involved in a domestic abuse incident. Nominated key adults within local schools will receive information from Norfolk Constabulary to afford them the opportunity of assessing the needs of the child during the school day and, should it be deemed appropriate to do so, to provide early support. Partners Norfolk Constabulary Norfolk County Council Norfolk Schools, Academies and Colleges Date Of Agreement June 2016 (Amended to comply with GDPR/ Data Protection Act 2018 – March 2019) Review Date August 2019 ISA Owner Superintendent Safeguarding ISA Author Information Sharing Officer (updated by Data Protection Reform Team, March 2019) Consultation Record Reviewer Date of Approval Data Protection Officer Head of Department owning the ISA Any Other Internal Stakeholders External Stakeholders Information Security Manager (where relevant) Information Asset Owner (s) Version Control Version No. Date Amendments Made Authorisation Vr 1 21/09/2018 CR Vr 2 25/09/2018 SC Vr 3 04/12/2018 SC Vr 4 06/12/2018 SC Vr 5 13/12/2018 SC Vr 6 18/12/2018 SC Vr 7 14/02/2019 SC Vr 8 21/02/2019 SC Vr 9 12/03/2019 SC 2 OFFICIAL Contents 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... -

Open PDF 260KB

Education Committee Oral evidence: Accountability hearings, HC 262 Tuesday 10 November 2020 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 10 November 2020. Watch the meeting Members present: Robert Halfon (Chair); Apsana Begum; Dawn Butler; Jonathan Gullis; Tom Hunt; Dr Caroline Johnson; Kim Johnson; David Johnston; Ian Mearns; David Simmonds; Christian Wakeford. Questions 417 - 515 Witnesses I: Amanda Spielman, Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector, Ofsted; and Yvette Stanley, National Director, Regulation and Social Care, Ofsted. Written evidence from witnesses: – [Add names of witnesses and hyperlink to submissions] Examination of witnesses Witnesses: Amanda Spielman and Yvette Stanley. Q417 Chair: Good morning, everyone. We are very pleased to have Ofsted here today addressing our Committee. For the benefit of the tape and those who are watching on the internet, could you kindly give your names and your position, and also if you are happy for us to address you with first names or whether you would like your full address. Amanda Spielman: I am very happy to be addressed by my first name. I am Amanda Spielman, and I am the Ofsted Chief Inspector. Yvette Stanley: Yvette Stanley, happy to be “Yvette”. I am the National Director for Regulation and Social Care at Ofsted. Q418 Chair: Thank you. Amanda, you published a report today. For the benefit of those watching, can you set out the key conclusions, as we have only heard what has been in the media? Amanda Spielman: We published a set of reports on early years, schools, further education, and children with special educational needs and disabilities. -

Uk Government and Special Advisers

UK GOVERNMENT AND SPECIAL ADVISERS April 2019 Housing Special Advisers Parliamentary Under Parliamentary Under Parliamentary Under Parliamentary Under INTERNATIONAL 10 DOWNING Toby Lloyd Samuel Coates Secretary of State Secretary of State Secretary of State Secretary of State Deputy Chief Whip STREET DEVELOPMENT Foreign Affairs/Global Salma Shah Rt Hon Tobias Ellwood MP Kwasi Kwarteng MP Jackie Doyle-Price MP Jake Berry MP Christopher Pincher MP Prime Minister Britain James Hedgeland Parliamentary Under Parliamentary Under Secretary of State Chief Whip (Lords) Rt Hon Theresa May MP Ed de Minckwitz Olivia Robey Secretary of State INTERNATIONAL Parliamentary Under Secretary of State and Minister for Women Stuart Andrew MP TRADE Secretary of State Heather Wheeler MP and Equalities Rt Hon Lord Taylor Chief of Staff Government Relations Minister of State Baroness Blackwood Rt Hon Penny of Holbeach CBE for Immigration Secretary of State and Parliamentary Under Mordaunt MP Gavin Barwell Special Adviser JUSTICE Deputy Chief Whip (Lords) (Attends Cabinet) President of the Board Secretary of State Deputy Chief of Staff Olivia Oates WORK AND Earl of Courtown Rt Hon Caroline Nokes MP of Trade Rishi Sunak MP Special Advisers Legislative Affairs Secretary of State PENSIONS JoJo Penn Rt Hon Dr Liam Fox MP Parliamentary Under Laura Round Joe Moor and Lord Chancellor SCOTLAND OFFICE Communications Special Adviser Rt Hon David Gauke MP Secretary of State Secretary of State Lynn Davidson Business Liason Special Advisers Rt Hon Amber Rudd MP Lord Bourne of -

Additional Information

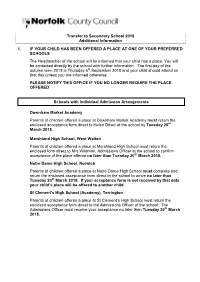

Transfer to Secondary School 2018 Additional Information 1. IF YOUR CHILD HAS BEEN OFFERED A PLACE AT ONE OF YOUR PREFERRED SCHOOLS The Headteacher of the school will be informed that your child has a place. You will be contacted directly by the school with further information. The first day of the autumn term 2018 is Thursday 6th September 2018 and your child should attend on that day unless you are informed otherwise. PLEASE NOTIFY THIS OFFICE IF YOU NO LONGER REQUIRE THE PLACE OFFERED Schools with Individual Admission Arrangements Downham Market Academy Parents of children offered a place at Downham Market Academy must return the enclosed acceptance form direct to Helen Driver at the school by Tuesday 20th March 2018. Marshland High School, West Walton Parents of children offered a place at Marshland High School must return the enclosed form direct to Mrs Wildman, Admissions Officer at the school to confirm acceptance of the place offered no later than Tuesday 20th March 2018. Notre Dame High School, Norwich Parents of children offered a place at Notre Dame High School must complete and return the enclosed acceptance form direct to the school to arrive no later than Tuesday 20th March 2018. If your acceptance form is not received by that date your child’s place will be offered to another child. St Clement’s High School (Academy), Terrington Parents of children offered a place at St Clement’s High School must return the enclosed acceptance form direct to the Admissions Officer of the school. The Admissions Officer must receive your acceptance no later than Tuesday 20th March 2018. -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

Let's Not Go Back to 70S Primary Education Wikio

This site uses cookies to help deliver services. By using this site, you agree to the use of cookies. Learn more Got it Conor's Commentary A blog about politics, education, Ireland, culture and travel. I am Conor Ryan, Dublin-born former adviser to Tony Blair and David Blunkett on education. Views expressed on this blog are written in a personal capacity. Friday, 20 February 2009 SUBSCRIBE FOR FREE UPDATES Let's not go back to 70s primary education Wikio Despite the Today programme's insistence on the term, "independent" is certainly not an apt Contact me description of today's report from the self-styled 'largest' review of primary education in 40 years. It You can email me here. is another deeply ideological strike against standards and effective teaching of the 3Rs in our primary schools. Many of its contributors oppose the very idea of school 'standards' and have an ideological opposition to external testing. They have been permanent critics of the changes of recent decades. And it is only in that light that the review's conclusions can be understood. Of course, there is no conflict between teaching literacy and numeracy, and the other subjects within the primary curriculum. And the best schools do indeed show how doing them all well provides a good and rounded education. Presenting this as the point of difference is a diversionary Aunt Sally. However, there is a very real conflict between recognising the need to single literacy and numeracy out for extra time over the other subjects as with the dedicated literacy and numeracy lessons, and making them just another aspect of primary schooling that pupils may or may not pick up along the way. -

Daily Report Thursday, 29 April 2021 CONTENTS

Daily Report Thursday, 29 April 2021 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 29 April 2021 and the information is correct at the time of publication (04:42 P.M., 29 April 2021). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 11 Energy Intensive Industries: ATTORNEY GENERAL 11 Biofuels 18 Crown Prosecution Service: Environment Protection: Job Training 11 Creation 19 Sentencing: Appeals 11 EU Grants and Loans: Iron and Steel 19 BUSINESS, ENERGY AND INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 12 Facebook: Advertising 20 Aviation and Shipping: Carbon Foreign Investment in UK: Budgets 12 National Security 20 Bereavement Leave 12 Help to Grow Scheme 20 Business Premises: Horizon Europe: Quantum Coronavirus 12 Technology and Space 21 Carbon Emissions 13 Horticulture: Job Creation 21 Clean Technology Fund 13 Housing: Natural Gas 21 Companies: West Midlands 13 Local Government Finance: Job Creation 22 Coronavirus: Vaccination 13 Members: Correspondence 22 Deep Sea Mining: Reviews 14 Modern Working Practices Economic Situation: Holiday Review 22 Leave 14 Overseas Aid: China 23 Electric Vehicles: Batteries 15 Park Homes: Energy Supply 23 Electricity: Billing 15 Ports: Scotland 24 Employment Agencies 16 Post Offices: ICT 24 Employment Agencies: Pay 16 Remote Working: Coronavirus 24 Employment Agency Standards Inspectorate and Renewable Energy: Finance 24 National Minimum Wage Research: Africa 25 Enforcement Unit 17 Summertime -

Ministerial Appointments, July 2018

Ministerial appointments, July 2018 Department Secretary of State Permanent Secretary PM The Rt Hon Theresa May MP The Rt Hon Brandon Lewis MP James Cleverly MP (Deputy Gavin Barwell (Chief of Staff) (Party Chairman) Party Chairman) Cabinet Office The Rt Hon David Lidington The Rt Hon Andrea Leadsom The Rt Hon Brandon Lewis MP Oliver Dowden CBE MP Chloe Smith MP (Parliamentary John Manzoni (Chief Exec of Sir Jeremy Heywood CBE MP (Chancellor of the MP (Lord President of the (Minister without portolio) (Parliamentary Secretary, Secretary, Minister for the the Civil Service) (Head of the Civil Duchy of Lancaster and Council and Leader of the HoC) Minister for Implementation) Constitution) Service, Cabinet Minister for the Cabinet Office) Secretary) Treasury (HMT) The Rt Hon Philip Hammond The Rt Hon Elizabeth Truss MP The Rt Hon Mel Stride MP John Glen MP (Economic Robert Jenrick MP (Exchequer Tom Scholar MP (Chief Secretary to the (Financial Secretary to the Secretary to the Treasury) Secretary to the Treasury) Treasury) Treasury) Ministry of Housing, The Rt Hon James Brokenshire Kit Malthouse MP (Minister of Jake Berry MP (Parliamentary Rishi Sunak (Parliamentary Heather Wheeler MP Lord Bourne of Aberystwyth Nigel Adams (Parliamentary Melanie Dawes CB Communities & Local MP State for Housing) Under Secretary of State and Under Secretary of State, (Parliamentary Under Secretary (Parliamentary Under Secretary Under Secretary of State) Government (MHCLG) Minister for the Northern Minister for Local Government) of State, Minister for Housing of State and Minister for Faith) Powerhouse and Local Growth) and Homelessness) Jointly with Wales Office) Business, Energy & Industrial The Rt Hon Greg Clark MP The Rt Hon Claire Perry MP Sam Gyimah (Minister of State Andrew Griffiths MP Richard Harrington MP The Rt Hon Lord Henley Alex Chisholm Strategy (BEIS) (Minister of State for Energy for Universities, Science, (Parliamentary Under Secretary (Parliamentary Under Secretary (Parliamentary Under Secretary and Clean Growth) Research and Innovation). -

The Need for Policy Stability in Education a Critique Of

THE NEED FOR POLICY STABILITY IN EDUCATION A CRITIQUE OF EDUCATION POLICY FORMATION: RESEARCH AND ANALYSIS (ENGLAND) In its 2015 analysis of education policy in the UK, as compared to other An Institute of Government report in 2017 described an jurisdictions, the OECD singled out the UK system as being particularly education environment of ‘costly policy change and churn: subject to churn. In the UK, ‘rather than build on the foundations laid by New organisations replace old ones; one policy is ended previous administrations, the temptation is always to scrap existing while a remarkably similar one is launched’ (Norris and Adam initiatives and start afresh’ (OECD 2015, 152). 2017, 3). Version 3.0 18.2.20 (see end for version control) V 2.0 17th December 2019 Wall, Warriner, Luck – December 2019 1 The need for policy stability in education: content 1. EXTENT OF POLICY CHANGE IN EDUCATION 2. EXAMPLES OF POLICY CHANGE AND CHURN 3. PROBLEMS CREATED BY CONSTANT CHANGE 4. INSTITUTIONAL ENABLERS OF CHANGE 5. FACTORS DRIVING SO MUCH CHANGE AND CHURN 6. LESSONS FROM OVERSEAS 7. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS Wall, Warriner, Luck – December 2019 2 EXTENT OF POLICY CHANGE IN EDUCATION Slides • Summary: policy change and churn is the dysfunctional characteristic of Education in England • There have been over 80 Government Acts relating to Education since 1979 • Education Acts have run at three to five times other departments • The House of Lords highlighted the greater issue with “secondary legislation” in 2009 • Statutory Instruments have run at an average of 88 per year since 1988 • Statutory Instruments determine policy in the most critical areas of Education • Education Acts are constantly reworked so there is no continuity • The extent of existing policy makes it incomprehensible Wall, Warriner, Luck – December 2019 3 There have been over 80 Acts relating to education since 1979 • Education in England is characterised by high levels of ‘policy churn’ and this is driven through government legislation. -

Secondary School Direct Salaried Kesgrave High School1

Secondary School Direct Salaried Encompass Kesgrave Notre Consortium, Tendring Samuel Ormiston High Dame High Chapel Road Tech. Ward Venture CASSA School School School College Academy 1 2 Consortium (SW Norfolk) Maths 7 4 2 3 1 - 1 Chemistry 3 2 1 1 - - - Physics 2 2 1 1 1 - - High priority High MFL 4 3 1 2 - - - Computer 2 2 1 2 1 - - Science English 9 6 1 4 1 1 - Biology 3 2 1 1 - - - History 4 3 2 - - - - Geography 3 2 1 1 - - - Priority RE 3 3 - - - - - Music 2 2 - 1 - - - DT 3 3 3 1 1 1 - PE 1 Art Drama Sociology These subjects may be available on a Psychology school-funded basis Business Other Other secondary Studies Media Studies The following also need to be added to the table above: Samuel Ward Academy: One maths place Tendring Technology College: One English, one DT, one PE The figures in the table indicate how many places are available for each subject within each Lead School. These are the partnership schools associated with each Lead School: 1 Kesgrave High School, Benjamin Britten High School, Copleston High School, County Upper School, Debenham High School, East Bergholt High School, Farlingaye High School, Felixstowe Academy, King Edward VI School, Mildenhall College, Ormiston Sudbury Academy, Pakefield High School, Stowmarket High School, Suffolk One Sixth Form College, Sir John Leman High School, Stradbroke High School, Suffolk New Academy, Thomas Mills High School, Thomas Gainsborough School, Westbourne Sports College 2 Notre Dame High School, Archbishop Sancroft School, Aylsham High School, Broadland High School, Caister High School, City of Norwich School, Cromer Academy, Dereham Northgate School, Lynn Grove High School, Reepham High School, Sheringham High School 3 Wymondham College, Taverham High School, Hartismere High School Please add to the footnote lists: Ormiston Venture Academy: Sewell Park School, Cliff Park school, Flegg High School CASSA: Linton Village College, Castle Manor Academy Tendring Technology College: To be confirmed . -

South East Coast

NHS South East Coast New MPs ‐ May 2010 Please note: much of the information in the following biographies has been taken from the websites of the MPs and their political parties. NHS BRIGHTON AND HOVE Mike Weatherley ‐ Hove (Cons) Caroline Lucas ‐ Brighton Pavillion (Green) Leader of the Green Party of England and Qualified as a Chartered Management Wales. Previously Green Party Member Accountant and Chartered Marketeer. of the European Parliament for the South From 1994 to 2000 was part owner of a East of England region. company called Cash Based in She was a member of the European Newhaven. From 2000 to 2005 was Parliament’s Environment, Public Health Financial Controller for Pete Waterman. and Food Safety Committee. Most recently Vice President for Finance and Administration (Europe) for the Has worked for a major UK development world’s largest non-theatrical film licensing agency providing research and policy company. analysis on trade, development and environment issues. Has held various Previously a Borough Councillor in positions in the Green Party since joining in 1986 and is an Crawley. acknowledged expert on climate change, international trade and Has run the London Marathon for the Round Table Children’s Wish peace issues. Foundation and most recently last year completed the London to Vice President of the RSPCA, the Stop the War Coalition, Campaign Brighton bike ride for the British Heart Foundation. Has also Against Climate Change, Railfuture and Environmental Protection completed a charity bike ride for the music therapy provider Nordoff UK. Member of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament National Robbins. Council and a Director of the International Forum on Globalization. -

Download the 12 Days of Canvas

SPECIAL CHRISTMAS EDITION 2018 BY THE12 DAYS OF CANVAS THE 12 DAYS OF CANVAS As 2018 draws to an end and the spirit of Christmas is upon us, at Saxton Bampfylde we have collated our own special series: ’The 12 Days of CANVAS’. This is a celebration of leadership from those we have had the honour of interviewing in 2018 for our insights publication, CANVAS. The open and honest thoughts individual was emphasised through reflected in these selected pieces many of our discussions, particularly highlight the depth of insight, as we enter a world of automation reflection, dedication and hopefulness and Artificial Intelligence. With this that exists amongst the leadership emphasis on human behaviour, all of of those sectors we work with. The our leaders highlighted the need to themes have been varied as would work more closely together, express be expected from conversations diversity of thought, and collaborate spanning so many sectors. However, through partnership working. what has shown is how much synergy exists across public, private We first started CANVAS in 2016 and not-for-profit life in the UK and and since then have produced 20 beyond. Change is a constant; that editions. Our readership has reached is overwhelmingly acknowledged. thousands of executives and board Political, economic, technological, leaders in the UK and globally. We and social change is everywhere. hope these selected interviews from This ever-changing environment has the past 12 months inspire, provoke given rise to a widespread focus on thought, start conversations and spur innovation. action. We hope you enjoy ‘The 12 days of CANVAS’ and welcome any Our conversations with leaders comments and thoughts you may made it clear that this is evident and have on the themes raised.