St Edmundsbury Cathedral Tower Tour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research Framework Revised.Vp

Frontispiece: the Norfolk Rapid Coastal Zone Assessment Survey team recording timbers and ballast from the wreck of The Sheraton on Hunstanton beach, with Hunstanton cliffs and lighthouse in the background. Photo: David Robertson, copyright NAU Archaeology Research and Archaeology Revisited: a revised framework for the East of England edited by Maria Medlycott East Anglian Archaeology Occasional Paper No.24, 2011 ALGAO East of England EAST ANGLIAN ARCHAEOLOGY OCCASIONAL PAPER NO.24 Published by Association of Local Government Archaeological Officers East of England http://www.algao.org.uk/cttees/Regions Editor: David Gurney EAA Managing Editor: Jenny Glazebrook Editorial Board: Brian Ayers, Director, The Butrint Foundation Owen Bedwin, Head of Historic Environment, Essex County Council Stewart Bryant, Head of Historic Environment, Hertfordshire County Council Will Fletcher, English Heritage Kasia Gdaniec, Historic Environment, Cambridgeshire County Council David Gurney, Historic Environment Manager, Norfolk County Council Debbie Priddy, English Heritage Adrian Tindall, Archaeological Consultant Keith Wade, Archaeological Service Manager, Suffolk County Council Set in Times Roman by Jenny Glazebrook using Corel Ventura™ Printed by Henry Ling Limited, The Dorset Press © ALGAO East of England ISBN 978 0 9510695 6 1 This Research Framework was published with the aid of funding from English Heritage East Anglian Archaeology was established in 1975 by the Scole Committee for Archaeology in East Anglia. The scope of the series expanded to include all six eastern counties and responsi- bility for publication passed in 2002 to the Association of Local Government Archaeological Officers, East of England (ALGAO East). Cover illustration: The excavation of prehistoric burial monuments at Hanson’s Needingworth Quarry at Over, Cambridgeshire, by Cambridge Archaeological Unit in 2008. -

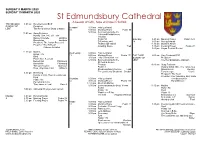

St Edmundsbury Cathedral

SUNDAY 12 MAY 2019 SUNDAY 19 MAY 2019 St Edmundsbury Cathedral A beacon of faith, hope and love in Suffolk THE FOURTH 8.00 am Holy Eucharist BCP SUNDAY OF President: Marianne Atkinson Tuesday 7.40 am Morning Prayer Psalms 16, 147.1-12 EASTER 14 8.00 am Holy Eucharist 10.00 am Sung Eucharist Matthias the 5.30 pm Solemn Eucharist Hymns: 807, 664, 671, 800 Apostle sung by the St Cecilia Chorale Missa Æterna Christi Munera Hymns: 165 (t.318), 213 (t.512) Palestrina Gloria How Benedictus Palestrina Saturday 8.45 am Morning Prayer Psalm 34 Cunningham in C 18 9.00 am Holy Eucharist President: The Ven Sally Gaze Panis Angelicus Franck 2.00 pm Funeral Preacher: Canon Tim Jones, DDO 3.30 pm Evening Prayer Psalm 84 Wednesday 7.40 am Morning Prayer Psalm 119.57-80 11.30 am Mattins 15 8.00 am Holy Eucharist Hymn: 234 THE FIFTH 8.00 am Holy Eucharist BCP 9.00 am Staff Prayers President: The Dean Mothersole SUNDAY OF 1.00 pm Holy Communion BCP Easter Anthems EASTER 5.30 pm Evensong sung by Men’s Voices Psalm 146 8.45 am Morning Prayer Harris Stanford in B flat Psalm 59 10.00 am Sung Eucharist for the Bury Festival Locus iste a deo factus est Hymns: 523, 675, 667, 471 I.1/I.2 Bruckner Missa Sancti Nicolai Haydn Let God arise Locke Benedictus Haydn 12.30 pm Holy Baptism President: The Canon Pastor 3.30 pm Evensong Thursday 7.40 am Morning Prayer Psalm 57 and Sub Dean Hymns: 457, 296 16 8.00 am Holy Eucharist Preacher: The Dean Mothersole 11.00 am Women in Fellowship Founders’ Psalms 113, 114 Day Service 12.30 pm Holy Baptism Brewer in D 12.30 pm Silent -

Music in Wells Cathedral 2016

Music in Wells Cathedral 2016 wellscathedral.org.uk Saturday 17 September 7.00pm (in the Quire) EARLY MUSIC WELLS: BACH CELLO SUITES BY CANDLELIGHT Some of the most beautiful music ever written for the cello, in the candlelit surroundings ofWells Cathedral, with one of Europe’s leading baroque cellists, Luise Buchberger (Co-Principal Cello of the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment): Suites No. 1 in G major, BWV 1007; No. 4 in E-flat major, BWV 1010; and No. 5 in C minor, BWV 1011 Tickets: £12.00; available from Wells Cathedral Shop Box Office and at the door Thursday 22 September 1.05 – 1.40pm (in the Quire) BACH COMPLETE ORGAN WORKS: RECITAL 11 The eleventh in the bi-monthly series of organ recitals surveying the complete organ works of J.S. Bach over six years – this year featuring the miscellaneous chorale preludes, alongside the ‘free’ organ works – played by Matthew Owens (Organist and Master of the Choristers,Wells Cathedral): Prelude in A minor, BWV 569; Kleines harmonisches Labyrinth, BWV 591; Chorale Preludes – Liebster Jesu, wir sind hier, BWV 706; Herr Jesu Christ, dich zu uns wend, BWVs 709, 726; Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott, BWV 720; BWV 726; Ach Gott, von Himmel sieh’ darein, BWV 741; Prelude and Fugue in A minor, BWV 543 Admission: free Retiring collection in aid of Wells Cathedral Music Saturday 24 September 7.00pm WELLS CATHEDRAL CHOIR IN CONCERT: FAURÉ REQUIEM Wells Cathedral Choir, Jonathan Vaughn (organ),Matthew Owens (conductor) In a fundraising concert forWells Cathedral, the world-famous choir sings one of the -

Comfort and Joy Journeying Through Advent with St Edmundsbury

26/11/2020 Weekly eNews 26 November 2020 Our regular round up of news and forthcoming events from our diocese View this email in your browser Thursday 26 November Printable version The Bishop of London, the Rt Revd Sarah Mullally, has welcomed the publication of the Government's Covid-19 Winter Plan, detailing that places of worship will be permitted to reopen for public worship from Wednesday 2 December. Information and guidance for churches during the Covid-19 pandemic is being updated. Please visit the Church of England page here and the Diocesan guidance page here for the most up to date information. Comfort and Joy There are many resources available on our website to help you plan Christmas 2020 please visit our new page here. A few highlights are detailed below: Reflections: Nine Lessons and Carols for Christmas for each day from Christmas Day to 2 January features contributions from Kate Bottley, Jonathan Bryan, Bob Chilcott, Martha Collison, Stephen Cottrell, Guli Francis- Dehqani, Chine McDonald, Sally Phillips and Justin Welby. Sign up here. Join Lightwave for Doorstep Carols on Wednesday 16 December 6.00-7.00pm - Parishes are warmly invited to organise carol singing on doorsteps across the county this Christmas to spread some much needed cheer and raise funds for local charities with the help of Radio Suffolk. Tune in to Radio Suffolk at Ipswich - 103.9 FM | West Suffolk - 104.6 FM | Lowestoft - 95.5 FM | Aldeburgh - 95.5 FM. This is on DAB and also on BBC Sounds. www.light-wave.org.uk. On Christmas Eve in East Bergholt Comfort and Joy will be bought to the village with a procession of 15 floats and two Nazarenes with a donkey. -

June 2019 at 10:30 Am

St Edmundsbury Cathedral A beacon of faith, hope and love in Suffolk CHAPTER MINUTES Minutes of the 191st Chapter Meeting held Tuesday 25 June 2019 at 10:30 am Attended: The Very Reverend Joe Hawes (JH) (Chair) The Revd Canon Matthew Vernon (MV) Canon Tim Allen (TA) Canon Charles Jenkin (CJ) Stewart Alderman (SA) Barbara Pycraft (BP) Dominic Holmes (DH) Michael Shallow (MS) Liz Steele (LS) Sarah-Jane Allison (SJA) Sally Gaze (SG) Present: Dominique Coshia (DC) Minute taker 1. Prayers and Welcome - The Dean opened the meeting with prayer. 2. Apologies for Absence 3. Notification of AOB A14 logo request The Old School Fund Sanctuary Housing Suffolk Pride 4. Minutes a) Review the Action Points from Chapter 07/05/2019 The action points of 7 May 19 were addressed and updated. b) Approve the Chapter minutes & confidential Chapter minutes from 07/05/2019 Amendments were made and the minutes were approved. c) Matters arising from the Chapter minutes 07/05/2019 TA proposed a review of all our property take place to include the Clergies’, Head Verger and other staff residences for us to have a true image of our property held and its potential for long- term income, allocation and best usage. JH and MV agreed with this proposal. d) Receive the minutes of the Finance meeting held 13/05/19 The minutes were approved with a date amendment. Discussions was had on the exact allocation of monies received by the Patron Scheme. JH confirmed money from the Patron scheme goes to the Foundation, which then goes into the accounts General Fund. -

Friends of St Edmundsbury Cathedral Choir Newsletter Spring 2017

Friends of St Edmundsbury Cathedral Choir Newsletter Spring 2017 Introduction A year ago we launched the new format FOCC newsletter and the feedback received was encouraging. This is the second edition and it again features items of news, events, articles by choristers past and present, as well as some gems from the archives. Fundraising remains an essential venture to support the Cathedral’s Choirs and ensure that key events The current economic climate such as tours and recordings can continues to be challenging, however, be maintained. The FOCC has the combination of innovative ideas had another active year and over and a very dedicated team has seen the following pages you will find a us, as a charity, continue to achieve snapshot of the many things that we impressive results. In the past year our do. activities have raised nearly £13,000. In this edition you will find some articles on past choir tours and fundraising for the 2018 event will be one of the main objectives in the year ahead. Being a chorister requires a significant commitment and the tours are valued highly. In addition to the prestige and the ambassadorial role, the tours are very educational and engender a wonderful esprit de corps. None of this would be possible without your support. It is a privilege to work with a skilled and motivated team, great spirited volunteers and the wonderful cathedral community. On behalf of the FOCC I would like to thank you all. Registered Charity Number: 1146575 Richard Franklin, Editor the FOCC made towards this Tour, From the Director of Music making it possible for everyone to It gives me great pleasure to contribute participate. -

Käthe Wright Kaufman Serves As Organ Scholar at St. Paul's

Käthe Wright Kaufman serves as organ scholar at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Rochester. She has been appointed organ scholar at Peterborough Cathedral in the UK from September 2019. Käthe was launched into church music early on when she became a chorister in the choir of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, Evanston, Illinois at age eight under the direction of Richard Webster. Her growing love of the Anglican choral tradition inspired her to begin her organ studies a few years later in 2007. She began studying with James Brown at the Music Institute of Chicago. For both undergraduate and graduate study, she attended the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York, where she studied organ, harpsichord, and improvisation with William Porter and Edoardo Bellotti, as well as organ with David Higgs for her Master’s degree. During her time at Eastman, Käthe worked as a Soprano section leader at the Church of the Ascension, as a VanDelinder Fellow at Christ Church, and as the organ scholar at Westminster Presbyterian Church in Buffalo. This exposure to many different styles and denominations of worship cemented in her the desire to work as a full- time church musician. Following the completion of her Bachelor of Music degree magna cum laude from the Eastman School of Music in 2016, Käthe spent a gap year in Truro, UK where she served as organ scholar at Truro Cathedral, playing two to three services a week, keeping the music library organized, and training the boy probationers every morning before school. Käthe hopes to work as a church musician in a large city, accompanying choirs and passing on her love of choral and organ repertoire to her choristers and congregation. -

St Edmundsbury Cathedral

SUNDAY 24 MARCH 2019 SUNDAY 31 MARCH 2019 St Edmundsbury Cathedral A beacon of faith, hope and love in Suffolk THIRD 8.00 am Holy Eucharist BCP SUNDAY OF President: The Canon Pastor and Tuesday 7.40 am Morning Prayer Psalm 9 LENT Sub Dean 26 8.00 am Holy Eucharist 5.30 pm Evensong sung by the 10.00 am Sung Eucharist St Cecilia Chorale Hymns: 755, 664, 358, 708 Ebdon 8.45 am Morning Prayer Psalm 31 Mass for Five Voices Byrd Psalm 64 Saturday 9.00 am Holy Eucharist Ave Verum Corpus Byrd Wise in F 30 3.30 pm Evensong sung by President: The Dean Forty days and forty nights Oxley Castle Choir Preacher: Bishop Graeme Knowles Carletti Praeludium in G minor Bruhns Wednesday 7.40 am Morning Prayer Psalm 38 Psalm 116 27 8.00 am Holy Eucharist 11.30 am Mattins Noble in B minor 9.00 am Staff Prayers Hymn: 425 O Lorde the maker of all thing 1.00 pm Holy Communion BCP Tomkins Joubert 4.30 pm Concert: St Cecilia Juniors Psalms 26 5.30 pm Evensong sung by Men’s Voices 8.00 am Holy Eucharist BCP Benedicte in F Dyson MOTHERING Harris SUNDAY President: The Canon Precentor Benedictus in C Stanford Psalm 39 Fantasia on ‘Aus der Tief’ Leighton 8.45 am Morning Prayer Wood in G Almighty God, who has me brought Ford O remember not Purcell Thursday 10.00 am Family Eucharist sung by the St 12.30 pm Holy Baptism Cecilia Chorale and St Cecilia 28 7.40 am Morning Prayer Psalm 56 Juniors Vigil of the 8.00 am Holy Eucharist 3.30 pm Solemn Evensong Hymns: 136, 557, 704 Annunciation 12.30 pm Silent Meditation Hymns: 188, 185 St Stephen’s Mass Ireland 5.30 pm Evensong -

Service Schedule 08 03 20

SUNDAY 8 MARCH 2020 SUNDAY 15 MARCH 2020 St Edmundsbury Cathedral A beacon of faith, hope and love in Suffolk THE SECOND 8.00 am Holy Eucharist BCP SUNDAY OF President: Tuesday 8.00 am Holy Eucharist LENT The Rev’d Canon David Crawley 10 8.30 am Morning Prayer Psalm 50 5.30 pm Evensong sung by the 10.00 am Sung Eucharist Colts and Probationers Hymns: 584, 140, 601, 818 Thomas Messe Solenelle Langlais Psalm 52 Saturday 8.45 am Morning Prayer Psalm 121 Benedictus Langlais Tell out my soul 14 9.00 am Holy Eucharist President: The Canon Precentor Faithful vigil ended 11.30 am Burial of Ashes Preacher: The Rt Revd Amazing Grace Trad 3.30 pm Evening Prayer Psalm 23 Graeme Knowles 5.00 pm Organ Festival Recital: 11.30 am Mattins Wednesday 8.00 am Holy Eucharist Hymn: 476 11 8.30 am Morning Prayer Psalm 111 THE THIRD 8.00 am Holy Eucharist BCP Byrd 1.00 pm Holy Communion BCP SUNDAY OF President: Psalm 74.1-7, 23-24 5.30 pm Evensong sung by the LENT The Rev’d Marianne Atkinson Benedictus Plainsong St Cecilia Juniors Benedicite Plainsong Thomas 10.00 am Sung Eucharist The Lamentation Bairstow Psalm 3 Hymns: 696(t.199), 115, 128(i), 652 Drop, drop slow tears Gibbons St Edmundsbury Service Todd Missa Brevis Berkley The Lord is my Shepherd Goodall Tantum ergo Vierne 3.30 pm Evensong President: The Dean Hymns: 416(ii), There’s a wideness Preacher: The Venerable Sally Gaze Byrd Thursday 8.00 am Holy Eucharist Archdeaecon for Psalm 135 12 8.30 am Morning Prayer Psalm 115 Rural Mission Purcell in G minor 12.30 pm Silent Meditation Thou knowest Lord Purcell -

November, at 10.30 Am

St Edmundsbury Cathedral A beacon of faith, hope and love in Suffolk CHAPTER MEETING Minutes of the 174th meeting of the Chapter Chapter Room, Wednesday 15th November, at 10.30 am Attended: Bishop Graeme Knowles (GK) (Chair) The Revd Canon Matthew Vernon (MV) Mr Stewart Alderman (SA) Canon Tim Allen (TA) The Revd Canon Philip Banks (PB) Mr Dominic Holmes (DH) The Revd Canon Charles Jenkin (CJ) Mrs Barbara Pycraft (BP) Mrs Elizabeth Steele (ES) Mr Michael Shallow (MS) Present: Ms Sarah-Jane Allison (SJA) Mr Michael Batty (MB) For Part Mrs Marie Taylor Stent (MTS) For part Mrs Lindsay James (LJ) (Minute taker) 1. Welcome and Prayers 2. Apologies for Absence Full attendance 3. Notification of AOB Chapter Input for appointing a new Dean (MV) 4. Minutes of Previous meetings a. To approve the minutes of the meeting held 16th October 2017. Following some minor corrections, the minutes were accepted as a final and accurate record for file and for signature. b. Matters Arising from the minutes of the meeting held 16th October 2017. None c. Action Points from 16th October 2017 were reviewed, and amended as necessary with completed items being removed. 5. Correspondence GK tabled an email received from Carol Fletcher, from the Commissioner’s Office. Chapter were disappointed with the outcome of the email, as they felt it did not reflect the meeting that was previously held. The collective decision was to move on and explore other avenues, as members felt the Commissioner’s Office was no longer a viable option. 6. Marie Taylor-Stent PR, Marketing and Events Report In November, SJA and SA invited Marie Taylor-Stent and Hannah Ratcliffe to meet with them to discuss their roles within the Cathedral. -

Our Bishops' Lent Challenge This Year Raises Awareness of Environmental

Our Bishops’ Lent Challenge this year raises awareness of environmental issues. Few of us can be unaware of the critical and urgent environmental challenges facing the world. Christians are rediscovering that caring for the creation God brought into being, and which God loves, is a vital part of our mission, as well as being an issue of justice. Our programme for Lent 2020 offers a range of opportunities to engage with this challenge: on your own, with others, listening to sermons and addresses, attending presentations, reading a Lent book, sharing in a Home Group, or giving up something for Lent and supporting a charity. The Church of England’s national Lent campaign is available in various formats: social media, an app, daily emails and booklets. Search for #LiveLent: Care for God’s Creation Lent Sunday Sermons and Meet the Preacher Following the 10.00 am Sunday Service you are welcome to discuss the sermon with the preacher over coffee or tea. Ending by 12 noon these conversations will take place in the Edmund Room. Sunday 1 March - Richard Stainer, Diocesan World Development Advisor Sunday 8 March - The Ven Sally Gaze, Archdeacon for Rural Mission Sunday 15 March - Bishop Graeme Knowles, Honorary Assistant Bishop Sunday 29 March - The Ven David Jenkins, Archdeacon of Sudbury Tuesday Evenings in Lent Climate Change and East Anglia A series of presentations in the Edmund Room on climate change related issues for this region, with questions and answers following each presentation. Free admission with presentation at 7.30 pm and evening ending by 9.00 pm. -

PHILIP ORCHARD. BA, Barch, RIBA

PHILIP ORCHARD. BA, BArch, RIBA Qualifications: 2005 AABC accredited for work on historic buildings 2003 Elected to the Art Workers Guild 1992 Royal Institute of British Architects 1988 RIBA Part III (Professional Practice Registered Architect) 1984 SPAB (Lethaby) Scholar 1983 University of Nottingham: Bachelor of Architecture (Hons) 1979 University of Nottingham: BA in Architecture and Environmental Science (Hons) Career: 2008- present The Whitworth Co-Partnership LLP – Member 1999 Cathedral Architect to the Dean and Chapter of St Edmundsbury. Approved inspecting architect for mediaeval churches in the Dioceses of Chelmsford, Ely, Norwich and St Edmundsbury 1998-2001 English Heritage Commissioned Architect 1991-2008 The Whitworth Co-Partnership - Partner 1992 Joint Surveyor to the Fabric of St Edmundsbury Cathedral 1985-1991 The Whitworth Co-Partnership 1983-1984 Percy Thomas Partnership, Nottingham 1979-1981 Percy Thomas Partnership, Nottingham General Expertise: The sensitive conservation, repair and refurbishment of listed buildings, projects from £2,000 to £1 million in value. The analysis, repair and adaptation of vernacular, domestic, churches, ruins and other historic structures, The reordering of buildings for worship and alternative uses. New design work in historic buildings. Responsibilities: Treasurer, The Cathedral Architects Association Member, SPAB Casework Panel Member, Ely Diocesan Advisory Committee for care of churches Member, St Edmundsbury & Ipswich Diocesan Advisory Committee Member, Ely Cathedral Fabric Advisory