The Evolutionary Origin of the Integument in Seed Plants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aphis Fabae Scop.) to Field Beans ( Vicia Faba L.

ANALYSIS OF THE DAMAGE CAUSED BY THE BLACK BEAN APHID ( APHIS FABAE SCOP.) TO FIELD BEANS ( VICIA FABA L.) BY JESUS ANTONIO SALAZAR, ING. AGR. ( VENEZUELA ) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF LONDON OCTOBER 1976 IMPERIAL COLLEGE FIELD STATION, SILWOOD PARK, SUNNINGHILL, ASCOT, BERKSHIRE. 2 ABSTRACT The concept of the economic threshold and its importance in pest management programmes is analysed in Chapter I. The significance of plant responses or compensation in the insect-injury-yield relationship is also discussed. The amount of damage in terms of yield loss that results from aphid attack, is analysed by comparing the different components of yield in infested and uninfested plants. In the former, plants were infested at different stages of plant development. The results showed that seed weights, pod numbers and seed numbers in plants infested before the flowering period were significantly less than in plants infested during or after the period of flower setting. The growth pattern and growth analysis in infested and uninfested plants have shown that the rate of leaf production and dry matter production were also more affected when the infestations occurred at early stages of plant development. When field beans were infested during the flowering period and afterwards, the aphid feeding did not affect the rate of leaf and dry matter production. There is some evidence that the rate of leaf area production may increase following moderate aphid attack during this period. The relationship between timing of aphid migration from the wintering host and the stage of plant development are shown to be of considerable significance in determining the economic threshold for A. -

Gymnosperms the MESOZOIC: ERA of GYMNOSPERM DOMINANCE

Chapter 24 Gymnosperms THE MESOZOIC: ERA OF GYMNOSPERM DOMINANCE THE VASCULAR SYSTEM OF GYMNOSPERMS CYCADS GINKGO CONIFERS Pinaceae Include the Pines, Firs, and Spruces Cupressaceae Include the Junipers, Cypresses, and Redwoods Taxaceae Include the Yews, but Plum Yews Belong to Cephalotaxaceae Podocarpaceae and Araucariaceae Are Largely Southern Hemisphere Conifers THE LIFE CYCLE OF PINUS, A REPRESENTATIVE GYMNOSPERM Pollen and Ovules Are Produced in Different Kinds of Structures Pollination Replaces the Need for Free Water Fertilization Leads to Seed Formation GNETOPHYTES GYMNOSPERMS: SEEDS, POLLEN, AND WOOD THE ECOLOGICAL AND ECONOMIC IMPORTANCE OF GYMNOSPERMS The Origin of Seeds, Pollen, and Wood Seeds and Pollen Are Key Reproductive SUMMARY Innovations for Life on Land Seed Plants Have Distinctive Vegetative PLANTS, PEOPLE, AND THE Features ENVIRONMENT: The California Coast Relationships among Gymnosperms Redwood Forest 1 KEY CONCEPTS 1. The evolution of seeds, pollen, and wood freed plants from the need for water during reproduction, allowed for more effective dispersal of sperm, increased parental investment in the next generation and allowed for greater size and strength. 2. Seed plants originated in the Devonian period from a group called the progymnosperms, which possessed wood and heterospory, but reproduced by releasing spores. Currently, five lineages of seed plants survive--the flowering plants plus four groups of gymnosperms: cycads, Ginkgo, conifers, and gnetophytes. Conifers are the best known and most economically important group, including pines, firs, spruces, hemlocks, redwoods, cedars, cypress, yews, and several Southern Hemisphere genera. 3. The pine life cycle is heterosporous. Pollen strobili are small and seasonal. Each sporophyll has two microsporangia, in which microspores are formed and divide into immature male gametophytes while still retained in the microsporangia. -

Oriental Bittersweet

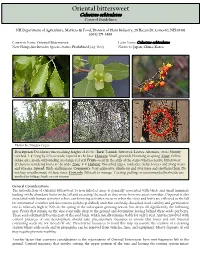

Oriental Bittersweet Department of Environmental Protection Environmental and Geographic Information Center 79 Elm St., Hartford, CT 06106 (860) 424-3540 Invasive Plant Information Sheet Asiatic Bittersweet, Oriental Bittersweet Celastrus orbiculatus Staff Tree Family (Celastraceae) Ecological Impact: Asiatic bittersweet is a rapidly spreading deciduous vine that threatens all vegetation in open and forested areas. It overtops other species and forms dense stands that shade out native vegetation. Trees and shrubs can be strangled by twining stems that twist around and eventually constrict the flow of plant fluids. Trees can be girdled and weighed down by vines in the canopies, making them more susceptible to damage by wind, snow, and ice storms. There is evidence that Asiatic bittersweet can hybridize with American bittersweet (Celastrus scandens), which occurs in similar habitats. Hybridization will destroy the genetic integrity of the native species. Control Methods: The most effective control method for Asiatic Bittersweet is to prevent establishment by annually monitoring for and removing small plants. Eradication of established plants is difficult due to the persistent seed bank in the soil. Larger plants are best controlled by cutting combined with herbicide treatment. Mechanical Control: Light infestations of a few small plants can be controlled by mowing or cutting vines and hand pulling roots. Weekly mowing can eradicate plants, but less frequent mowing ( 2-3 times per year) will only stimulate root suckering. Cutting and uprooting plants is best done before fruiting. Vines with fruits should be bagged and disposed of in the trash to prevent seed dispersal. Heavy infestations can be controlled by cutting vines and immediately treating cut stems with herbicide. -

Morphology and Anatomy of Foliar Nectaries and Associated Leaves in Mallotus (Euphorbiaceae) Thomas S

Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany Volume 11 | Issue 1 Article 3 1985 Morphology and Anatomy of Foliar Nectaries and Associated Leaves in Mallotus (Euphorbiaceae) Thomas S. Elias Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden Sun An-Ci The Chinese Academy of Sciences Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Elias, Thomas S. and An-Ci, Sun (1985) "Morphology and Anatomy of Foliar Nectaries and Associated Leaves in Mallotus (Euphorbiaceae)," Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany: Vol. 11: Iss. 1, Article 3. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso/vol11/iss1/3 ALISO 11(1),1985, pp. 17-25 MORPHOLOGY AND ANATOMY OF FOLIAR NECTARIES AND ASSOCIATED LEAVES IN MALLOTUS (EUPHORBIACEAE) THOMAS S. ELIAS Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden Claremont, California 91711 AND SUN AN-CI Institute of Botany 141 Hsi Chih Men Wai Ta Chie Beijing, People's Republic of China ABSTRACT The morphology and anatomy of the foliar nectaries and associated leaves offour species of Mallotus (Euphorbiaceae) were studied. Light microscopic observations of paraffin- and plastic-embedded spec imens were complemented with scanning electron micrographs. Leaf anatomy of the four species is typical of large mesophytic plants. Aattened foliar nectaries are shown to be composed of specialized epidermal cells. The nonvascularized nectaries consist of narrow columnar cells each with a large nucleus, numerous vacuoles, and dense cytoplasm. Subglandular parenchyma cells have more pro nounced nuclei, more vacuoles and denser cytoplasm than do typical laminar parenchyma. Structurally, these nectaries are similar to those found in other taxa of Euphorbiaceae and in other families of flowering plants. -

Bruxner Park Flora Reserve Working Plan

Bruxner Park Flora Reserve Working Plan Working Plan for Bruxner Park Flora Reserve No 3 Upper North East Forest Agreement Region North East Region Contents Page 1. DETAILS OF THE RESERVE 2 1.1 Introduction 2 1.2 Location 2 1.3 Key Attributes of the Reserve 2 1.4 General Description 2 1.5 History 6 1.6 Current Usage 8 2. SYSTEM OF MANAGEMENT 9 2.1 Objectives of Management 9 2.2 Management Strategies 9 2.3 Management Responsibility 11 2.4 Monitoring, Reporting and Review 11 3. LIST OF APPENDICES 11 Appendix 1 Map 1 Locality Appendix 1 Map 2 Cadastral Boundaries, Forest Types and Streams Appendix 1 Map 3 Vegetation Growth Stages Appendix 1 Map 4 Existing Occupation Permits and Recreation Facilities Appendix 2 Flora Species known to occur in the Reserve Appendix 3 Fauna records within the Reserve Y:\Tourism and Partnerships\Recreation Areas\Orara East SF\Bruxner Flora Reserve\FlRWP_Bruxner.docx 1 Bruxner Park Flora Reserve Working Plan 1. Details of the Reserve 1.1 Introduction This plan has been prepared as a supplementary plan under the Nature Conservation Strategy of the Upper North East Ecologically Sustainable Forest Management (ESFM) Plan. It is prepared in accordance with the terms of section 25A (5) of the Forestry Act 1916 with the objective to provide for the future management of that part of Orara East State Forest No 536 set aside as Bruxner Park Flora Reserve No 3. The plan was approved by the Minister for Forests on 16.5.2011 and will be reviewed in 2021. -

Edge-Biased Distributions of Insects. a Review

Agronomy for Sustainable Development (2018) 38: 11 https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-018-0488-4 REVIEW ARTICLE Edge-biased distributions of insects. A review Hoang Danh Derrick Nguyen1 & Christian Nansen 1,2 Accepted: 15 January 2018 /Published online: 5 February 2018 # The Author(s) 2018. This article is an open access publication Abstract Spatial ecology includes research into factors responsible for observed distribution patterns of organisms. Moreover, the spatial distribution of an animal at a given spatial scale and in a given landscape may provide valuable insight into its host preference, fitness, evolutionary adaptation potential, and response to resource limitations. In agro-ecology, in-depth understanding of spatial distributions of insects is of particular importance when the goals are to (1) promote establishment and persistence of certain food webs, (2) maximize performance of pollinators and natural enemies, and (3) develop precision-targeted monitoring and detection of emerging outbreaks of herbivorous pests. In this article, we review and discuss a spatial phenomenon that is widespread among insect species across agricultural systems and across spatial scales—they tend to show “edge-biased distributions” (spatial distribution patterns show distinct “edge effects”). In the conservation and biodiversity literature, this phenomenon has been studied and reviewed intensively in the context of how landscape fragmentation affects species diversity. However, possible explanations of, and also implications of, edge-biased distributions of insects in agricultural systems have not received the same attention. Our review suggests that (1) mathe- matical modeling approaches can partially explain edge-biased distributions and (2) abiotic factors, crop vegetation traits, and environmental parameters are factors that are likely responsible for this phenomenon. -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

Regional Landscape Surveillance for New Weed Threats Project 2016-2017

State Herbarium of South Australia Botanic Gardens and State Herbarium Economic & Sustainable Development Group Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources Milestone Report Regional Landscape Surveillance for New Weed Threats Project 2016-2017 Milestone: Annual report on new plant naturalisations in South Australia Chris J. Brodie, Jürgen Kellermann, Peter J. Lang & Michelle Waycott June 2017 Contents Summary .................................................................................................................................... 3 1. Activities and outcomes for 2016/2017 financial year .......................................................... 3 Funding .................................................................................................................................. 3 Activities ................................................................................................................................ 4 Outcomes and progress of weeds monitoring ........................................................................ 6 2. New naturalised or questionably naturalised records of plants in South Australia. .............. 7 3. Description of newly recognised weeds in South Australia .................................................. 9 4. Updates to weed distributions in South Australia, weed status and name changes ............. 23 References ................................................................................................................................ 28 Appendix 1: Activities of the -

Oriental Bittersweet Orientalcelastrus Bittersweet Orbiculatus Controlcontrol Guidelinesguidelines

Oriental bittersweet OrientalCelastrus bittersweet orbiculatus ControlControl GuidelinesGuidelines NH Department of Agriculture, Markets & Food, Division of Plant Industry, 29 Hazen Dr, Concord, NH 03301 (603) 271-3488 Common Name: Oriental Bittersweet Latin Name: Celastrus orbiculatus New Hampshire Invasive Species Status: Prohibited (Agr 3800) Native to: Japan, China, Korea Photos by: Douglas Cygan Description: Deciduous vine reaching heights of 40-60'. Bark: Tannish, furrowed. Leaves: Alternate, ovate, bluntly toothed, 3-4'' long by 2/3’s as wide, tapered at the base. Flowers: Small, greenish, blooming in spring. Fruit: Yellow dehiscent capsule surrounding an orange-red aril. Fruits occur in the axils of the stems whereas native bittersweet (Celastrus scandens) fruits at the ends. Zone: 4-8. Habitat: Disturbed edges, roadsides, fields, forests and along rivers and streams. Spread: Birds and humans. Comments: Very aggressive, climbs up and over trees and smothers them. Do not buy wreaths made of these vines. Controls: Difficult to manage. Cutting, pulling, or recommended herbicide use applied to foliage, bark, or cut-stump. General Considerations The introduction of Oriental bittersweet to non infested areas is generally associated with birds and small mammals feeding on the abundant fruits in the fall and excreting the seeds as they move from one area to another. Dispersal is also associated with human activities where earth moving activities occur or when the vines and fruits are collected in the fall for ornamental wreathes and decorations (which is prohibited) and then carelessly discarded. Seed viability and germination rate is relatively high at 90% in the spring of the subsequent growing season, but drops off significantly the following year. -

Stillingia: a Newly Recorded Genus of Euphorbiaceae from China

Phytotaxa 296 (2): 187–194 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/pt/ PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2017 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.296.2.8 Stillingia: A newly recorded genus of Euphorbiaceae from China SHENGCHUN LI1, 2, BINGHUI CHEN1, XIANGXU HUANG1, XIAOYU CHANG1, TIEYAO TU*1 & DIANXIANG ZHANG1 1 Key Laboratory of Plant Resources Conservation and Sustainable Utilization, South China Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou 510650, China 2University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China * Corresponding author, email: [email protected] Abstract Stillingia (Euphorbiaceae) contains ca. 30 species from Latin America, the southern United States, and various islands in the tropical Pacific and in the Indian Ocean. We report here for the first time the occurrence of a member of the genus in China, Stillingia lineata subsp. pacifica. The distribution of the genus in China is apparently narrow, known only from Pingzhou and Wanzhou Islands of the Wanshan Archipelago in the South China Sea, which is close to the Pearl River estuary. This study updates our knowledge on the geographic distribution of the genus, and provides new palynological data as well. Key words: Island, Hippomaneae, South China Sea, Stillingia lineata Introduction During the last decade, hundreds of new plant species or new species records have been added to the flora of China. Nevertheless, newly described or newly recorded plant genera are not discovered and reported very often, suggesting that botanical expedition and plant survey at the generic level may be advanced in China. As far as we know, only six and eight angiosperm genera respectively have been newly described or newly recorded from China within the last ten years (Qiang et al. -

Anza-Borrego Desert State Park Bibliography Compiled and Edited by Jim Dice

Steele/Burnand Anza-Borrego Desert Research Center University of California, Irvine UCI – NATURE and UC Natural Reserve System California State Parks – Colorado Desert District Anza-Borrego Desert State Park & Anza-Borrego Foundation Anza-Borrego Desert State Park Bibliography Compiled and Edited by Jim Dice (revised 1/31/2019) A gaggle of geneticists in Borrego Palm Canyon – 1975. (L-R, Dr. Theodosius Dobzhansky, Dr. Steve Bryant, Dr. Richard Lewontin, Dr. Steve Jones, Dr. TimEDITOR’S Prout. Photo NOTE by Dr. John Moore, courtesy of Steve Jones) Editor’s Note The publications cited in this volume specifically mention and/or discuss Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, locations and/or features known to occur within the present-day boundaries of Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, biological, geological, paleontological or anthropological specimens collected from localities within the present-day boundaries of Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, or events that have occurred within those same boundaries. This compendium is not now, nor will it ever be complete (barring, of course, the end of the Earth or the Park). Many, many people have helped to corral the references contained herein (see below). Any errors of omission and comission are the fault of the editor – who would be grateful to have such errors and omissions pointed out! [[email protected]] ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As mentioned above, many many people have contributed to building this database of knowledge about Anza-Borrego Desert State Park. A quantum leap was taken somewhere in 2016-17 when Kevin Browne introduced me to Google Scholar – and we were off to the races. Elaine Tulving deserves a special mention for her assistance in dealing with formatting issues, keeping printers working, filing hard copies, ignoring occasional foul language – occasionally falling prey to it herself, and occasionally livening things up with an exclamation of “oh come on now, you just made that word up!” Bob Theriault assisted in many ways and now has a lifetime job, if he wants it, entering these references into Zotero. -

Arils As Food of Tropical American Birds

Condor, 82:3142 @ The Cooper Ornithological society 1980 ARILS AS FOOD OF TROPICAL AMERICAN BIRDS ALEXANDER F. SKUTCH ABSTRACT.-In Costa Rica, 16 kinds of trees, lianas, and shrubs produce arillate seeds which are eaten by 95 species of birds. These are listed and compared with the birds that feed on the fruiting spikes of Cecropia trees and berries of the melastome Miconia trinervia. In the Valley of El General, on the Pacific slope of southern Costa Rica, arillate seeds and berries are most abundant early in the rainy season, from March to June or July, when most resident birds are nesting and northbound migrants are leaving or passing through. The oil-rich arils are a valuable resource for nesting birds, especially honeycreepers and certain woodpeck- ers, and they sustain the migrants. Vireos are especially fond of arils, and Sulphur-bellied Flycatchers were most numerous when certain arillate seeds were most abundant. Many species of birds take arils from the same tree or vine without serious competition. However, at certain trees with slowly opening pods, birds vie for the contents while largely neglecting other foods that are readily available. Although many kinds of fruits eaten by during the short time that the seed remains birds may be distinguished morphological- in the alimentary tract of a small bird. ly, functionally they fall into two main Wallace (1872) described how the Blue- types, exemplified by the berry and the pod tailed Imperial Pigeon (Duculu concinnu) containing arillate seeds. Berries and ber- swallows the seed of the nutmeg (Myristicu rylike fruits are generally indehiscent; no frugruns) and, after digesting the aril or hard or tough integument keeps animals mace, casts up the seed uninjured.