HOUR Town Paul Glover and the Genesis and Evolution of Ithaca HOURS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SAGA COMMUNICATIONS, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

2017 Annual Report 2017 Annual Letter To our fellow shareholders: Every now and then I am introduced to someone who knows, kind of, who I am and what I do and they instinctively ask, ‘‘How are things at Saga?’’ (they pronounce it ‘‘say-gah’’). I am polite and correct their pronunciation (‘‘sah-gah’’) as I am proud of the word and its history. This is usually followed by, ‘‘What is a ‘‘sah-gah?’’ My response is that there are several definitions — a common one from 1857 deems a ‘‘Saga’’ as ‘‘a long, convoluted story.’’ The second one that we prefer is ‘‘an ongoing adventure.’’ That’s what we are. Next they ask, ‘‘What do you do there?’’ (pause, pause). I, too, pause, as by saying my title doesn’t really tell what I do or what Saga does. In essence, I tell them that I am in charge of the wellness of the Company and overseer and polisher of the multiple brands of radio stations that we have. Then comes the question, ‘‘Radio stations are brands?’’ ‘‘Yes,’’ I respond. ‘‘A consistent allusion can become a brand. Each and every one of our radio stations has a created personality that requires ongoing care. That is one of the things that differentiates us from other radio companies.’’ We really care about the identity, ambiance, and mission of each and every station that belongs to Saga. We have radio stations that have been on the air for close to 100 years and we have radio stations that have been created just months ago. -

Racker News Outlets Spreadsheet.Xlsx

RADIO Station Contact Person Email/Website/Phone Cayuga Radio Group (95.9; 94.1; 95.5; 96.7; 103.7; 99.9; 97.3; 107.7; 96.3; 97.7 FM) Online Form https://cyradiogroup.com/advertise/ WDWN (89.1 FM) Steve Keeler, Telcom Dept. Chairperson (315) 255-1743 x [email protected] WSKG (89.3 FM) Online Form // https://wskg.org/about-us/contact-us/ (607) 729-0100 WXHC (101.5 FM) PSA Email (must be recieved two weeks in advance) [email protected] WPIE -- ESPN Ithaca https://www.espnithaca.com/advertise-with-us/ (107.1 FM; 1160 AM) Stephen Kimball, Business Development Manager [email protected], (607) 533-0057 WICB (91.7 FM) Molli Michalik, Director of Public Relations [email protected], (607) 274-1040 x extension 7 For Programming questions or comments, you can email WITH (90.1 FM) Audience Services [email protected], (607) 330-4373 WVBR (93.5 FM) Trevor Bacchi, WVBR Sales Manager https://www.wvbr.com/advertise, [email protected] WEOS (89.5 FM) Greg Cotterill, Station Manager (315) 781-3456, [email protected] WRFI (88.1 FM) Online Form // https://www.wrfi.org/contact/ (607) 319-5445 DIGITAL News Site Contact Person Email/Website/Phone CNY Central (WSTM) News Desk [email protected], (315) 477-9446 WSYR Events Calendar [email protected] WICZ (Fox 40) News Desk [email protected], (607) 798-0070 WENY Online Form // https://www.weny.com/events#!/ Adversiting: [email protected], (607) 739-3636 WETM James Carl, Digital Media and Operations Manager [email protected], (607) 733-5518 WIVT (Newschannel34) John Scott, Local Sales Manager (607) 771-3434 ex.1704 WBNG Jennifer Volpe, Account Executive [email protected], (607) 584-7215 www.syracuse.com/ Online Form // https://www.syracuse.com/placead/ Submit an event: http://myevent.syracuse.com/web/event.php PRINT Newspaper Contact Person Email/Website/Phone Tompkins Weekly Todd Mallinson, Advertising Director [email protected], (607) 533-0057 Ithaca Times Jim Bilinski, Advertising Director [email protected], (607) 277-7000 ext. -

SAGA COMMUNICATIONS, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

2016 Annual Report 2016 Annual Letter To our fellow shareholders: Well…. here we go. This letter is supposed to be my turn to tell you about Saga, but this year is a little different because it involves other people telling you about Saga. The following is a letter sent to the staff at WNOR FM 99 in Norfolk, Virginia. Directly or indirectly, I have been a part of this station for 35+ years. Let me continue this train of thought for a moment or two longer. Saga, through its stockholders, owns WHMP AM and WRSI FM in Northampton, Massachusetts. Let me share an experience that recently occurred there. Our General Manager, Dave Musante, learned about a local grocery/deli called Serio’s that has operated in Northampton for over 70 years. The 3rd generation matriarch had passed over a year ago and her son and daughter were having some difficulties with the store. Dave’s staff came up with the idea of a ‘‘cash mob’’ and went on the air asking people in the community to go to Serio’s from 3 to 5PM on Wednesday and ‘‘buy something.’’ That’s it. Zero dollars to our station. It wasn’t for our benefit. Community outpouring was ‘‘just overwhelming and inspiring’’ and the owner was emotionally overwhelmed by the community outreach. As Dave Musante said in his letter to me, ‘‘It was the right thing to do.’’ Even the local newspaper (and local newspapers never recognize radio) made the story front page above the fold. Permit me to do one or two more examples and then we will get down to business. -

Draft Final Environmental Assessment November 2008 Draft Final Environmental Assessment November 2008

Draft Final Environmental Assessment November 2008 Draft Final Environmental Assessment November 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 CHAPTER 1 - EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1-1 1.1 Introduction 1-1 1.2 Purpose and Need 1-2 1.2.1 Where is the Action Located? 1-2 1.2.2 Why is the Action Needed? 1-2 1.3 What are the Objectives/Purposes of the Action? 1-7 1.4 What Alternative(s) Are Being Considered? 1-7 1.5 Which Alternative is Preferred? 1-8 1.6 How Was the Number of Affected Large Trucks Estimated? 1-8 1.7 What Are the Constraints in Developing Regulatory Alternatives? 1-8 1.8 How will the Alternative(s) Affect the Environment? 1-9 1.9 Anticipated Permits/Certifications/Coordination 1-9 1.10 Social, Economic and Environmental Impacts 1-9 1.11 What are the Costs & Schedules? 1-9 1.12 Who Will Decide Which Alternative Will Be Selected And How Can I Be Involved In This Decision? 1-11 CHAPTER 2 - ACTION CONTEXT: HISTORY, TRANSPORTATION PLANS, CONDITIONS AND NEEDS 2-1 2.1 Action History 2-1 2.2 Transportation Plans and Land Use 2-4 2.2.1 Local Plans for the Action Area 2-4 2.2.1.1 Local Master Plan 2-4 2.2.1.2 Local Private Development Plans 2-5 2.2.2 Transportation Corridor 2-5 2.2.2.1 Importance of Routes 2-5 2.2.2.2 Alternate Routes 2-5 2.2.2.3 Corridor Deficiencies and Needs 2-5 2.2.2.4 Transportation Plans 2-5 2.2.2.5 Abutting Highway Segments and Future Plans for Abutting Highway Segments 2-6 2.3 Transportation Conditions, Deficiencies and Engineering Considerations 2-6 2.3.1 Operations (Traffic and Safety) & Maintenance 2-6 2.3.1.1 Functional Classification -

Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 May

Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 May 8, 2015 DA 15-556 In Reply Refer to: 1800B3-HOD Released: May 8, 2015 Nathaniel J. Hardy, Esq. Marashlian & Donahue, LLC – The Commlaw Group 1420 Spring Hill Road, Suite 401 McLean, VA 22102 Gary S. Smithwick, Esq. Smithwick & Belendiuk, P.C. 5028 Wisconsin Avenue, NW, Suite 301 Washington, DC 20016 In re: Saga Communications of New England, LLC WFIZ(AM), Odessa, NY Facility ID No. 36406 File No. BRH-20140131AGJ W235BR, Ithaca, NY Facility ID No. 144458 File No. BRFT-20140131AGM W242AB, Ithaca, NY Facility ID No. 20647 File No. BRFT-20140131AGL W299BI, Ithaca, NY Facility ID No. 138598 File No. BRFT-20140131AGK WHCU(AM), Ithaca, NY Facility ID No. 18048 File No. BR-20140130ANA WIII(FM), Cortland, NY Facility ID No. 9427 File No. BRH-20140130AMU W262AD, Ithaca, NY Facility ID No. 9429 File No. BRFT-20140130AMV WNYY(AM), Ithaca, NY Facility ID No. 32391 File No. BR-20140130AMS W249CD, Ithaca, NY Facility ID No. 156452 File No. BRFT-20140130AMT WQNY(FM), Ithaca, NY Facility ID No. 32390 File No. BRH-20140130AMQ WYXL(FM), Ithaca, NY Facility ID No. 18051 File No. BRH-20140130AMJ W244CZ, Ithaca, NY Facility ID No. 151643 File No. BRFT-20140130AMM W254BF, Ithaca, NY Facility ID No. 25008 File No. BRFT-20140130AML W277BS, Ithaca, NY Facility ID No. 24216 File No. BRFT-20140130AMK Renewal Applications Petition to Deny Dear Counsel: We have before us the applications (“Applications”) of Saga Communications of New England, LLC (“Saga”) for renewal of its licenses for the above-referenced radio stations and FM translators (collectively, “Stations”). -

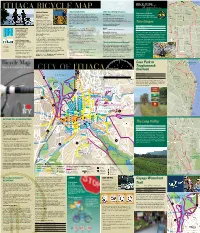

Bicycle Map Ithaca and Tompkins County 2016

ITHACA BICYCLE MAP BIKESuggestions RIDE Visitors Centers Bike-Friendly Events Other Local Biking Resources Finger Lakes Cycling Club What’s the best way to travel and enjoy your time in Bicycle Rentals East Shore Visitors Center Cue sheets for these suggested routes (800)284-8422 Ithaca and Tompkins County? By bike, of course! Check Contact the Visitors Center for information. and more available online at FLCycling.org 904 E. Shore Dr., Ithaca out all of these events around town that are bike-friendly and get ready for a fun filled ride around some of the city’s Cornell Bicycle and Pedestrian Website Our flagship visitors center is best music events, food festivals, fundraisers, and more! www.bike.cornell.edu, and the bike map is at your one-stop source for travel For complete event information, head to transportation.fs.cornell.edu/file/Bike_map_web-10.pdf information, activities, and events http://www.VisitIthaca.com Two Gorges in Ithaca, Tompkins County, the Bombers Bikes (Ithaca College) Finger Lakes Region and Spring www.ithaca.edu/orgs/bbikes Start: Taughannock State Park surrounding New York State. The self-service lobby, open Mileage: 28 miles Ithaca-Tompkins County 24/7, is stocked with maps and key information on accom- Streets Alive - StreetsAliveIthaca.com Way2Go www. www.ccetompkins.org/community/way2go Transportation Council modations, attractions and activities. Open year-round, Ithaca Festival - http://www.IthacaFestival.org Description: Moderate 121 East Court Street 6-7 days per week. Hours vary by season. Mountain Bike Information Summer This ride connects two of the outdoor jewels of our area Ithaca, New York 14850 Shindagin Hollow State Forest Phone: (607) 274-5570 Downtown Visitors Center –– Taughannock Falls State Park and Robert H. -

2015 Annual Report 2015 Annual Letter to Our Fellow Shareholders

2015 Annual Report 2015 Annual Letter To our fellow shareholders: Although another year has zoomed by, 2015 seems like it was 2014 all over again. The good news is that we are still here and we have used some of our excess cash for significant and cogent acquisitions. We will get into that shortly, but first a small commercial about broadcasting. I have always, since childhood, been fascinated by magic and magicians. I even remember, very early in my life, reading the magazine PARADE that came with the Sunday newspaper. Inside the back page were small ads that promoted everything from the ‘‘best new rug shampooer’’ to one that seemed to run each week. It was about a three inch ad and the headline always stopped me -- ‘‘MYSTERIES OF THE UNIVERSE REVEALED!’’...Wow... All I had to do was write away and some organization called the Rosicrucian’s would send me a pamphlet and correspondent courses revealing all to me. Well, my mother nixed that idea really fast. It didn’t stop my interest in magic and mysticism. I read all I could about Harry Houdini and, especially, Howard Thurston. Orson Welles called Howard Thurston ‘‘The Master’’ and, though today he is mostly forgotten except among magicians, he was truly a gifted magician and a magical performer. His competitor was Harry Houdini, whose name survived though his magic had a tragic end. If you are interested, you should take some time and research these two performers. In many ways, their magic and their shows tie into what we do today in both radio and TV. -

Decentralized Utilization Incentives in Electronic Cash Jeremy Lloyd Rubin

Decentralized Utilization Incentives in Electronic Cash by Jeremy Lloyd Rubin Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Engineering in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2016 ○c Jeremy Lloyd Rubin, MMXVI. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Author................................................................ Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science May 17, 2016 Certified by . Ronald Rivest Institute Professor Thesis Supervisor Accepted by. Dr. Christopher J. Terman Chairman, Master of Engineering Thesis Committee 2 Decentralized Utilization Incentives in Electronic Cash by Jeremy Lloyd Rubin Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science on May 17, 2016, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Engineering in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Abstract Many mechanisms exist in centralized systems that incentivize resource utilization. For example, central governments use inflation for many reasons, but a common justification for inflation in practice is as a means to incentivize resource utilization. Incentives to utilize resource may stimulate economic growth. However, the asymmetry of economic control and potential abuses of power implicit in centralized systems may be undesirable. An electronic cash design may be able to create resource utlization incentives via decentralized mechanisms. Decentralized mechanisms may be economically sustainable without centralized and potentially coercive forces. We propose Hourglass, a novel electronic cash design that provides a decentralized mechanism to encourage utilization via expiration dates. -

A Basic Critique of Economic Arguments for Local Currencies By

A Basic Critique of Economic Arguments for Local Currencies By Ian M. Schmutte For Monetary Theory and Policy Economics 420 Winter 2002 Schmutte - 2 I. INTRODUCTION One of the most ubiquitous features of any modern economy is its money system. Present in the majority of economic transactions, money plays a key role in the facilitation of exchange, and represents a common denomination of the value that individuals, and society, place on goods and services. Simultaneously, and somewhat paradoxically, monetary systems, and the institutional landscape in which they function have a certain invisibility. Each person takes it for granted that every other person will accept money at an understood value. For this reason, money, and the historical context in which it arose, fades into the background. However, for some critics, the origin of centralized national fiat money systems is not forgotten. Authors such as Vera Smith, Friedrich Hayek, and Milton Friedman1 have argued in various forms against government central banking. A common thread of these arguments is that government monopoly of the money supply does not provide any benefits to the public. Rather, a competitive market-based system of money issue can optimally generate a medium of exchange that is stable in value and in sufficient supply. Recently academics and community activists have issued different critiques of nationalized fiat money systems. On their view, the current monetary system contributes to underdevelopment of cities and regions, unnecessary unemployment, and environmental degradation. They envision a process of monetary decentralization in which a network of “local” or “community currencies” flourishes. Such systems would 1 These arguments are outlined in Vera Smith, The Rationale of Central Banking and the Free Banking Alternative (Indianapolis: Liberty Press, 1990). -

A Revealing Interview with Dr. Karl Schutz Creator of Chemainus Dollars

CCMAGAZINE A Revealing Interview With Dr. Karl Schutz Creator of Chemainus Dollars June 2010 COMMUNITY CURREN C Y MAGAZINE MAR C H -APRIL 2010 ISSUE § 1 2 § COMMUNITY CURREN C Y MAGAZINE MAR C H -APRIL 2010 ISSUE New Local Currency Projects 5 & Other Efforts 8 Community Currency Fund Project Chemainus Dollars 10 Creating a Local Money Masterpiece An Interview with Dr. Karl Schutz Bernal Bucks Makes Baby Steps 20 Towards Local Currency Implementation by Mira Luna Community Forge: 22 Here’s Why We’re Going Freemium Salads and skill-sharing: What makes a community money 24 system into a “community glue” by Rebecca Reider TimeBanking, LETS and Madison 28 Hours & the Big Picture by Stephanie Rearick on the Madison Hours blog CC - Conf 16-17 February Février 31 febrero, 2011, Lyons, France CALL FOR PAPERS 36 A History of Ithaca HOURs January 2000, by Paul Glover COMMUNITY CURREN C Y MAGAZINE MAR C H -APRIL 2010 ISSUE § 3 “ëks” - Page 8 [email protected] Skype IM ‘digitalcurrency’ http://twitter.com/dgcmagazine Community Currency Magazine is published online 6-12 times a year. Subscriptions and related advertisements are free. © 2009-2010 Community Currency Magazine All Rights Reserved Legal Notice/Disclaimer: Articles and advertisements in this magazine are not and should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to sell any investment. All material in this issue is based on information obtained from sources believed to be reliable but which have not been independently verified; CCmag, the editor and contributors make no guarantee, representation or warranty and accept no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. -

Inns, Lodges & Villas

KLMNO F6 EZ EE SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 23, 2012 The Impulsive Traveler IF YOU GO GETTING THERE Spending a few Hours in Ithaca, N.Y. US Airways offers one-stop flights from Washington Dulles to Ithaca, with late- September flights currently starting at BY MELANIE D.G. KAPLAN $324 round-trip. After summer vacation in Canada, I WHERE TO STAY briefly mourned the loss of colored bills La Tourelle Resort & Spa in my billfold. But the gloom was short- 1150 Danby Rd. lived. On my drive home, I took a detour 800-765-1492 to Ithaca, N.Y., which I’d heard has its www.latourelle.com own currency. By day’s end, my wallet About three miles from downtown, swelled again with delightfully colorful backing up to Buttermilk Falls State money. In place of notes adorned with Park, pet-friendly. Rooms from $149 images of dead presidents, there were weekdays and $189 weekends through playful bills with pictures of salamanders mid-November. and steamboats. It’s only fitting that this town — as Hilton Garden Inn Ithaca dense with brainpower as it is with 130 E. Seneca St. composting bins — would have a quirky 607-277-8900 alternative currency system. I set out, www.ithaca.hgi.com over a few days, to use the money for as Downtown, on the Commons, with a many of my purchases as possible. What I complimentary shuttle to and from the didn’t expect was the adventure I faced Ithaca airport, Cornell University and just trying to find places to spend the Ithaca College. Rooms from $179 during salamanders. -

Resource Transformation Through Capitalization

RESOURCE TRANSFORMATION THROUGH CAPITALIZATION PROCESSES IN COMMUNITY ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT A DISSERTATION IN Economics & Social Sciences Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by JONATHAN DAVID RAMSE B.A., Wartburg College, 2007 M.A., University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2014 Kansas City, Missouri 2019 © 2019 JONATHAN DAVID RAMSE ALL RIGHTS RESERVED RESOURCE TRANSFORMATION THROUGH CAPITALIZATION PROCESSES IN COMMUNITY ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT Jonathan David Ramse, Candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2019 ABSTRACT This dissertation presents a critical institutionalist theory of resource transformation through capitalization processes in the context of community economic development. The arguments are presented through three articles. The first chapter is introductory and provides a synthesis of the main arguments in the articles that follow. The first article (Chapter II) provides a brief conceptual history of the term ‘capital’ and continues by articulating a capital as process. The Community Capitals Framework provides several insights that shape the conception of resources and their use in the context of community economic development. A metatheoretic framework is developed in which emergent resource capitalization processes are seen as a social relation through which agents, constrained and enabled by both resource structures and cultural systems, pursue their development agendas by utilizing those resources they have access to in order to transform them into resources they desire. iii The second article (Chapter III) seeks to identify a set of processional properties associated with capitalization processes. The eight properties are identified as: transformation capacity, temporality, cultural embeddedness, expected future yield, identifiability, flexibility, reliability, and variability/conditionality.