Local Currency Loans and Grants: Comparative Case Studies of Ithaca HOURS and Calgary Dollars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SAGA COMMUNICATIONS, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

2017 Annual Report 2017 Annual Letter To our fellow shareholders: Every now and then I am introduced to someone who knows, kind of, who I am and what I do and they instinctively ask, ‘‘How are things at Saga?’’ (they pronounce it ‘‘say-gah’’). I am polite and correct their pronunciation (‘‘sah-gah’’) as I am proud of the word and its history. This is usually followed by, ‘‘What is a ‘‘sah-gah?’’ My response is that there are several definitions — a common one from 1857 deems a ‘‘Saga’’ as ‘‘a long, convoluted story.’’ The second one that we prefer is ‘‘an ongoing adventure.’’ That’s what we are. Next they ask, ‘‘What do you do there?’’ (pause, pause). I, too, pause, as by saying my title doesn’t really tell what I do or what Saga does. In essence, I tell them that I am in charge of the wellness of the Company and overseer and polisher of the multiple brands of radio stations that we have. Then comes the question, ‘‘Radio stations are brands?’’ ‘‘Yes,’’ I respond. ‘‘A consistent allusion can become a brand. Each and every one of our radio stations has a created personality that requires ongoing care. That is one of the things that differentiates us from other radio companies.’’ We really care about the identity, ambiance, and mission of each and every station that belongs to Saga. We have radio stations that have been on the air for close to 100 years and we have radio stations that have been created just months ago. -

Racker News Outlets Spreadsheet.Xlsx

RADIO Station Contact Person Email/Website/Phone Cayuga Radio Group (95.9; 94.1; 95.5; 96.7; 103.7; 99.9; 97.3; 107.7; 96.3; 97.7 FM) Online Form https://cyradiogroup.com/advertise/ WDWN (89.1 FM) Steve Keeler, Telcom Dept. Chairperson (315) 255-1743 x [email protected] WSKG (89.3 FM) Online Form // https://wskg.org/about-us/contact-us/ (607) 729-0100 WXHC (101.5 FM) PSA Email (must be recieved two weeks in advance) [email protected] WPIE -- ESPN Ithaca https://www.espnithaca.com/advertise-with-us/ (107.1 FM; 1160 AM) Stephen Kimball, Business Development Manager [email protected], (607) 533-0057 WICB (91.7 FM) Molli Michalik, Director of Public Relations [email protected], (607) 274-1040 x extension 7 For Programming questions or comments, you can email WITH (90.1 FM) Audience Services [email protected], (607) 330-4373 WVBR (93.5 FM) Trevor Bacchi, WVBR Sales Manager https://www.wvbr.com/advertise, [email protected] WEOS (89.5 FM) Greg Cotterill, Station Manager (315) 781-3456, [email protected] WRFI (88.1 FM) Online Form // https://www.wrfi.org/contact/ (607) 319-5445 DIGITAL News Site Contact Person Email/Website/Phone CNY Central (WSTM) News Desk [email protected], (315) 477-9446 WSYR Events Calendar [email protected] WICZ (Fox 40) News Desk [email protected], (607) 798-0070 WENY Online Form // https://www.weny.com/events#!/ Adversiting: [email protected], (607) 739-3636 WETM James Carl, Digital Media and Operations Manager [email protected], (607) 733-5518 WIVT (Newschannel34) John Scott, Local Sales Manager (607) 771-3434 ex.1704 WBNG Jennifer Volpe, Account Executive [email protected], (607) 584-7215 www.syracuse.com/ Online Form // https://www.syracuse.com/placead/ Submit an event: http://myevent.syracuse.com/web/event.php PRINT Newspaper Contact Person Email/Website/Phone Tompkins Weekly Todd Mallinson, Advertising Director [email protected], (607) 533-0057 Ithaca Times Jim Bilinski, Advertising Director [email protected], (607) 277-7000 ext. -

SAGA COMMUNICATIONS, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

2016 Annual Report 2016 Annual Letter To our fellow shareholders: Well…. here we go. This letter is supposed to be my turn to tell you about Saga, but this year is a little different because it involves other people telling you about Saga. The following is a letter sent to the staff at WNOR FM 99 in Norfolk, Virginia. Directly or indirectly, I have been a part of this station for 35+ years. Let me continue this train of thought for a moment or two longer. Saga, through its stockholders, owns WHMP AM and WRSI FM in Northampton, Massachusetts. Let me share an experience that recently occurred there. Our General Manager, Dave Musante, learned about a local grocery/deli called Serio’s that has operated in Northampton for over 70 years. The 3rd generation matriarch had passed over a year ago and her son and daughter were having some difficulties with the store. Dave’s staff came up with the idea of a ‘‘cash mob’’ and went on the air asking people in the community to go to Serio’s from 3 to 5PM on Wednesday and ‘‘buy something.’’ That’s it. Zero dollars to our station. It wasn’t for our benefit. Community outpouring was ‘‘just overwhelming and inspiring’’ and the owner was emotionally overwhelmed by the community outreach. As Dave Musante said in his letter to me, ‘‘It was the right thing to do.’’ Even the local newspaper (and local newspapers never recognize radio) made the story front page above the fold. Permit me to do one or two more examples and then we will get down to business. -

Draft Final Environmental Assessment November 2008 Draft Final Environmental Assessment November 2008

Draft Final Environmental Assessment November 2008 Draft Final Environmental Assessment November 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 CHAPTER 1 - EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1-1 1.1 Introduction 1-1 1.2 Purpose and Need 1-2 1.2.1 Where is the Action Located? 1-2 1.2.2 Why is the Action Needed? 1-2 1.3 What are the Objectives/Purposes of the Action? 1-7 1.4 What Alternative(s) Are Being Considered? 1-7 1.5 Which Alternative is Preferred? 1-8 1.6 How Was the Number of Affected Large Trucks Estimated? 1-8 1.7 What Are the Constraints in Developing Regulatory Alternatives? 1-8 1.8 How will the Alternative(s) Affect the Environment? 1-9 1.9 Anticipated Permits/Certifications/Coordination 1-9 1.10 Social, Economic and Environmental Impacts 1-9 1.11 What are the Costs & Schedules? 1-9 1.12 Who Will Decide Which Alternative Will Be Selected And How Can I Be Involved In This Decision? 1-11 CHAPTER 2 - ACTION CONTEXT: HISTORY, TRANSPORTATION PLANS, CONDITIONS AND NEEDS 2-1 2.1 Action History 2-1 2.2 Transportation Plans and Land Use 2-4 2.2.1 Local Plans for the Action Area 2-4 2.2.1.1 Local Master Plan 2-4 2.2.1.2 Local Private Development Plans 2-5 2.2.2 Transportation Corridor 2-5 2.2.2.1 Importance of Routes 2-5 2.2.2.2 Alternate Routes 2-5 2.2.2.3 Corridor Deficiencies and Needs 2-5 2.2.2.4 Transportation Plans 2-5 2.2.2.5 Abutting Highway Segments and Future Plans for Abutting Highway Segments 2-6 2.3 Transportation Conditions, Deficiencies and Engineering Considerations 2-6 2.3.1 Operations (Traffic and Safety) & Maintenance 2-6 2.3.1.1 Functional Classification -

Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 May

Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 May 8, 2015 DA 15-556 In Reply Refer to: 1800B3-HOD Released: May 8, 2015 Nathaniel J. Hardy, Esq. Marashlian & Donahue, LLC – The Commlaw Group 1420 Spring Hill Road, Suite 401 McLean, VA 22102 Gary S. Smithwick, Esq. Smithwick & Belendiuk, P.C. 5028 Wisconsin Avenue, NW, Suite 301 Washington, DC 20016 In re: Saga Communications of New England, LLC WFIZ(AM), Odessa, NY Facility ID No. 36406 File No. BRH-20140131AGJ W235BR, Ithaca, NY Facility ID No. 144458 File No. BRFT-20140131AGM W242AB, Ithaca, NY Facility ID No. 20647 File No. BRFT-20140131AGL W299BI, Ithaca, NY Facility ID No. 138598 File No. BRFT-20140131AGK WHCU(AM), Ithaca, NY Facility ID No. 18048 File No. BR-20140130ANA WIII(FM), Cortland, NY Facility ID No. 9427 File No. BRH-20140130AMU W262AD, Ithaca, NY Facility ID No. 9429 File No. BRFT-20140130AMV WNYY(AM), Ithaca, NY Facility ID No. 32391 File No. BR-20140130AMS W249CD, Ithaca, NY Facility ID No. 156452 File No. BRFT-20140130AMT WQNY(FM), Ithaca, NY Facility ID No. 32390 File No. BRH-20140130AMQ WYXL(FM), Ithaca, NY Facility ID No. 18051 File No. BRH-20140130AMJ W244CZ, Ithaca, NY Facility ID No. 151643 File No. BRFT-20140130AMM W254BF, Ithaca, NY Facility ID No. 25008 File No. BRFT-20140130AML W277BS, Ithaca, NY Facility ID No. 24216 File No. BRFT-20140130AMK Renewal Applications Petition to Deny Dear Counsel: We have before us the applications (“Applications”) of Saga Communications of New England, LLC (“Saga”) for renewal of its licenses for the above-referenced radio stations and FM translators (collectively, “Stations”). -

Volume 23 - Issue 2

IJCCR International Journal of Community Currency Research SUMMER 2019 VOLUME 23 - ISSUE 2 www.ijccr.net IJCCR 23 (Summer 2019) – ISSUE 2 Editorial 1 Georgina M. Gómez Transforming or reproducing an unequal economy? Solidarity and inequality 2-16 in a community currency Ester Barinaga Key Factors for the Durability of Community Currencies: An NPO Management 17-34 Perspective Jeremy September Sidechain and volatility of cryptocurrencies based on the blockchain 35-44 technology Olivier Hueber Social representations of money: contrast between citizens and local 45-62 complementary currency members Ariane Tichit INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF COMMUNITY CURRENCY RESEARCH 2017 VOLUME 23 (SUMMER) 1 International Journal of Community Currency Research VOLUME 23 (SUMMER) 1 EDITORIAL Georgina M. Gómez (*) Chief Editor International Institute of Social Studies of Erasmus University Rotterdam (*) [email protected] The International Journal of Community Currency Research was founded 23 years ago, when researchers on this topic found a hard time in getting published in other peer reviewed journals. In these two decades the academic publishing industry has exploded and most papers can be published internationally with a minimal peer-review scrutiny, for a fee. Moreover, complementary currency research is not perceived as extravagant as it used to be, so it has now become possible to get published in journals with excellent reputation. In that context, the IJCCR is still the first point of contact of practitioners and new researchers on this topic. It offers open access, free publication, and it is run on a voluntary basis by established scholars in the field. In any of the last five years, it has received about 25000 views. -

Complementary Currencies: an Analysis of the Creation Process Based on Sustainable Local Development Principles

sustainability Article Complementary Currencies: An Analysis of the Creation Process Based on Sustainable Local Development Principles Francisco Javier García-Corral 1,* , Jaime de Pablo-Valenciano 2 , Juan Milán-García 2 and José Antonio Cordero-García 3 1 Research Group: Almeria Group of Applied Economy (SEJ-147), University of Almeria, 04120 Almeria, Spain 2 Department of Business and Economics, Applied Economic Area, University of Almeria, 04120 Almeria, Spain; [email protected] (J.d.P.-V.); [email protected] (J.M.-G.) 3 Department of Law, Financial and Tax Law, University of Almeria, 04120 Almeria, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 1 July 2020; Accepted: 13 July 2020; Published: 15 July 2020 Abstract: Complementary currencies are a reality and are being applied both globally and locally. The aim of this article is to explain the viability of this type of currency and its application in local development, in this case, in a rural mountain municipality in the province of Almería (Spain) called Almócita. The Plus, Minus, Interesting (PMI); “Flying Balloon”; and Strength, Weakness, Opportunity (SWOT) analysis methodologies will be used to carry out the study. Finally, a ranking of success factors will be carried out with a brainstorming exercise. As to the results, there are, a priori, more advantages than disadvantages of implementing these currencies, but the local population has clarified that their main concern is depopulation along with a lack of varied work. As a counterpart to this and strengths or advantages, almost all the participants mention the support from the Almócita city council and the initiatives that are constantly being promoted. -

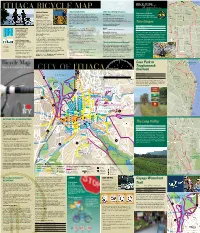

Bicycle Map Ithaca and Tompkins County 2016

ITHACA BICYCLE MAP BIKESuggestions RIDE Visitors Centers Bike-Friendly Events Other Local Biking Resources Finger Lakes Cycling Club What’s the best way to travel and enjoy your time in Bicycle Rentals East Shore Visitors Center Cue sheets for these suggested routes (800)284-8422 Ithaca and Tompkins County? By bike, of course! Check Contact the Visitors Center for information. and more available online at FLCycling.org 904 E. Shore Dr., Ithaca out all of these events around town that are bike-friendly and get ready for a fun filled ride around some of the city’s Cornell Bicycle and Pedestrian Website Our flagship visitors center is best music events, food festivals, fundraisers, and more! www.bike.cornell.edu, and the bike map is at your one-stop source for travel For complete event information, head to transportation.fs.cornell.edu/file/Bike_map_web-10.pdf information, activities, and events http://www.VisitIthaca.com Two Gorges in Ithaca, Tompkins County, the Bombers Bikes (Ithaca College) Finger Lakes Region and Spring www.ithaca.edu/orgs/bbikes Start: Taughannock State Park surrounding New York State. The self-service lobby, open Mileage: 28 miles Ithaca-Tompkins County 24/7, is stocked with maps and key information on accom- Streets Alive - StreetsAliveIthaca.com Way2Go www. www.ccetompkins.org/community/way2go Transportation Council modations, attractions and activities. Open year-round, Ithaca Festival - http://www.IthacaFestival.org Description: Moderate 121 East Court Street 6-7 days per week. Hours vary by season. Mountain Bike Information Summer This ride connects two of the outdoor jewels of our area Ithaca, New York 14850 Shindagin Hollow State Forest Phone: (607) 274-5570 Downtown Visitors Center –– Taughannock Falls State Park and Robert H. -

Canadian Numismatic Journal Index to Volume 16, 1971

CANADIAN NUMISMATIC JOURNAL INDEX TO VOLUME 16, 1971 Key to the page numbers given in this index 1- 32 - January 205-244 - July-August 33- 68 - February 245-280 - September 69-100 - March 281-316 - October 101-136 -April 317-348 - November 137-172 - May 349-384 - December 173-204-June -A A Visit to the Tower Mint, London, (1663) . 45 A Story of Coincidence - Arthur F. Giere .. 107 -B- BOOK REVIEWS Arroyo, Carmen - Coins of Haiti 1803-1970 ... 18 Betton, James L. - Money Talks: A Numismatic Anthology... .. 83 Caston, Carlos-Duros Del Mundo 1831-1971 335 Coffee, Jr., John M. -Atwood's Catalogue of United States and Canadian Transportation Tokens . 156 1972 Coin Monthly Year Book . 292 Falcke, George and Clarke, Robert L. - India's 1862 Rupees 293 Gardiakos, Soterios - A Catalogue of the Coins of Dalmatia and Albania 18 Harris, Robert P. - Gold Coins of the Americas . 331 Haxby, J. A. and Willey, R. C. - Coins of Canada. 186, 266 Irwin, Ross W. - War Medals and Decorations of Canada 266 Kane, Paul W., and Marvin, Robert W., - Numismatics in the Classroom 367 Lambros, Paul - Gold Coins of Philippi . 18 Numismatic Issues of the Franklin Mint . 187 Remick, Jerome; James, Somer; DowIe, Anthony; and Patrick Finn The Guidebook and Catalogue of British Commonwealth Coins, 1649-1971 .. 156 Seaby, Peter and Bussell, Monica - British Tokens and Their Values. 157 Seppa, Dale - Paper Money of Paraguay and Uruguay . 187 Smith, R. B. - The Anglo-Hanoverian Coinage . 292 Stickney, Brian R. - Numismatic History of Republic of Panama 267 Tomlinson, Geoffrey W. -Australian Bank Notes, 1817-1963 263 Trowbridge, Richard J. -

2015 Annual Report 2015 Annual Letter to Our Fellow Shareholders

2015 Annual Report 2015 Annual Letter To our fellow shareholders: Although another year has zoomed by, 2015 seems like it was 2014 all over again. The good news is that we are still here and we have used some of our excess cash for significant and cogent acquisitions. We will get into that shortly, but first a small commercial about broadcasting. I have always, since childhood, been fascinated by magic and magicians. I even remember, very early in my life, reading the magazine PARADE that came with the Sunday newspaper. Inside the back page were small ads that promoted everything from the ‘‘best new rug shampooer’’ to one that seemed to run each week. It was about a three inch ad and the headline always stopped me -- ‘‘MYSTERIES OF THE UNIVERSE REVEALED!’’...Wow... All I had to do was write away and some organization called the Rosicrucian’s would send me a pamphlet and correspondent courses revealing all to me. Well, my mother nixed that idea really fast. It didn’t stop my interest in magic and mysticism. I read all I could about Harry Houdini and, especially, Howard Thurston. Orson Welles called Howard Thurston ‘‘The Master’’ and, though today he is mostly forgotten except among magicians, he was truly a gifted magician and a magical performer. His competitor was Harry Houdini, whose name survived though his magic had a tragic end. If you are interested, you should take some time and research these two performers. In many ways, their magic and their shows tie into what we do today in both radio and TV. -

Doc ~ Alternative Currencies « Read

Alternative currencies \ PDF \\ MQLTCZJO8P Alternative currencies By - Reference Series Books LLC Jan 2012, 2012. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 246x189x7 mm. This item is printed on demand - Print on Demand Neuware - Source: Wikipedia. Pages: 47. Chapters: Community currencies, Private currencies, Local currency, Local Exchange Trading Systems, Ithaca Hours, Silvio Gesell, Freiwirtschaft, UIC franc, Freigeld, Liberty Dollar, Findhorn Ecovillage, Stelo, History of Chatham Islands numismatics, Emissions Reduction Currency System, Private currency, List of community currencies in the United States, Cornish currency, Community Exchange System, Complementary currency, BerkShares, RAAM, Digital currency exchanger, Time-based currency, Antarctican dollar, Potomac, Quasi Universal Intergalactic Denomination, Crédito, Chiemgauer, Disney dollar, Lewes Pound, WIR Bank, Neutral Unit of Construction, Terra, Kelantanese dinar, Totnes pound, Ecosimia, Eco-Pesa, PLENTY, Detroit Community Scrip, Hero Card, Toronto dollar, Stroud pound, Calgary Dollar, Fourth Corner Exchange, Fureai kippu, Occitan, Eco-Money, Multi registry system, Abeille, SOL Project, Acmetal, Saber, Urstromtaler, Nagorno-Karabakh dram, Instrodi, Flex dollar, Seborga luigino, Ora, Ural franc, Sectoral currency, Uned, Aspen dollar. Excerpt: The Liberty Dollar (ALD) was a private currency produced in the United States. The currency was embodied in minted metal rounds similar to coins, gold and silver certificates and electronic currency (eLD). ALD certificates are 'warehouse receipts' for real gold and silver owned by... READ ONLINE [ 8.26 MB ] Reviews This ebook can be worthy of a read, and much better than other. I have read and i am certain that i am going to planning to go through again once again in the future. You may like just how the writer compose this book. -

Decentralized Utilization Incentives in Electronic Cash Jeremy Lloyd Rubin

Decentralized Utilization Incentives in Electronic Cash by Jeremy Lloyd Rubin Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Engineering in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2016 ○c Jeremy Lloyd Rubin, MMXVI. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Author................................................................ Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science May 17, 2016 Certified by . Ronald Rivest Institute Professor Thesis Supervisor Accepted by. Dr. Christopher J. Terman Chairman, Master of Engineering Thesis Committee 2 Decentralized Utilization Incentives in Electronic Cash by Jeremy Lloyd Rubin Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science on May 17, 2016, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Engineering in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Abstract Many mechanisms exist in centralized systems that incentivize resource utilization. For example, central governments use inflation for many reasons, but a common justification for inflation in practice is as a means to incentivize resource utilization. Incentives to utilize resource may stimulate economic growth. However, the asymmetry of economic control and potential abuses of power implicit in centralized systems may be undesirable. An electronic cash design may be able to create resource utlization incentives via decentralized mechanisms. Decentralized mechanisms may be economically sustainable without centralized and potentially coercive forces. We propose Hourglass, a novel electronic cash design that provides a decentralized mechanism to encourage utilization via expiration dates.