Water, Culture and Power: Anthropological Perspectives from ‘Down Under’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019-2020 Annual Report and Financial Statements

ANNUAL REPORT and FINANCIAL STATEMENTS - for the year ended 31 MARCH 2020 STATEMENTS REPORT and FINANCIAL ANNUAL The Museum, 41 Long Street, Devizes, Wiltshire. SN10 1NS Telephone: 01380 727369 www.wiltshiremuseum.org.uk Our Audiences Our audiences are essential and work is ongoing, with funding through the Wessex Museums Partnership, to understand our audiences and develop projects and facilities to ensure they remain at the core of our activities. Our audience includes visitors, Society members, school groups, community groups, and researchers. Above: testimonial given in February 2020 by one of our visitors. Below: ‘word cloud’ comprising the three words used to describe the Museum on the audience forms during 2019/20. Cover: ‘Chieftain 1’ by Ann-Marie James© Displayed in ‘Alchemy: Artefacts Reimagined’, an exhibition of contemporary artworks by Ann-Marie James. Displayed at Wiltshire Museum May-August 2020. (A company limited by guarantee) Charity Number 1080096 Company Registration Number 3885649 SUMMARY and OBJECTS The Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Researchers. Every year academic researchers Society (the Society) was founded in 1853. The carry out important research on the collection. Society’s first permanent Museum opened in There are over 500,000 items in the collections Long Street in 1874. The Society is a registered and details can be found in our online searchable charity and governed by Articles of Association. database. The collections are ‘Designated’ of national importance and ‘Accreditation’ status Objects. To educate the public by promoting, was first awarded in 2005. Overseen by the fostering interest in, exploration, research and Arts Council the Accreditation Scheme sets publication on the archaeology, art, history and out nationally-agreed standards, which inspire natural history of Wiltshire for the public benefit. -

Sacred Places Europe: 108 Destinations

Reviews from Sacred Places Around the World “… the ruins, mountains, sanctuaries, lost cities, and pilgrimage routes held sacred around the world.” (Book Passage 1/2000) “For each site, Brad Olsen provides historical background, a description of the site and its special features, and directions for getting there.” (Theology Digest Summer, 2000) “(Readers) will thrill to the wonderful history and the vibrations of the world’s sacred healing places.” (East & West 2/2000) “Sites that emanate the energy of sacred spots.” (The Sunday Times 1/2000) “Sacred sites (to) the ruins, sanctuaries, mountains, lost cities, temples, and pilgrimage routes of ancient civilizations.” (San Francisco Chronicle 1/2000) “Many sacred places are now bustling tourist and pilgrimage desti- nations. But no crowd or souvenir shop can stand in the way of a traveler with great intentions and zero expectations.” (Spirituality & Health Summer, 2000) “Unleash your imagination by going on a mystical journey. Brad Olsen gives his take on some of the most amazing and unexplained spots on the globe — including the underwater ruins of Bimini, which seems to point the way to the Lost City of Atlantis. You can choose to take an armchair pilgrimage (the book is a fascinating read) or follow his tips on how to travel to these powerful sites yourself.” (Mode 7/2000) “Should you be inspired to make a pilgrimage of your own, you might want to pick up a copy of Brad Olsen’s guide to the world’s sacred places. Olsen’s marvelous drawings and mysterious maps enhance a package that is as bizarre as it is wonderfully acces- sible. -

Sacred Places Europe: 108 Destinations

Reviews from Sacred Places Around the World “… the ruins, mountains, sanctuaries, lost cities, and pilgrimage routes held sacred around the world.” (Book Passage 1/2000) “For each site, Brad Olsen provides historical background, a description of the site and its special features, and directions for getting there.” (Theology Digest Summer, 2000) “(Readers) will thrill to the wonderful history and the vibrations of the world’s sacred healing places.” (East & West 2/2000) “Sites that emanate the energy of sacred spots.” (The Sunday Times 1/2000) “Sacred sites (to) the ruins, sanctuaries, mountains, lost cities, temples, and pilgrimage routes of ancient civilizations.” (San Francisco Chronicle 1/2000) “Many sacred places are now bustling tourist and pilgrimage desti- nations. But no crowd or souvenir shop can stand in the way of a traveler with great intentions and zero expectations.” (Spirituality & Health Summer, 2000) “Unleash your imagination by going on a mystical journey. Brad Olsen gives his take on some of the most amazing and unexplained spots on the globe — including the underwater ruins of Bimini, which seems to point the way to the Lost City of Atlantis. You can choose to take an armchair pilgrimage (the book is a fascinating read) or follow his tips on how to travel to these powerful sites yourself.” (Mode 7/2000) “Should you be inspired to make a pilgrimage of your own, you might want to pick up a copy of Brad Olsen’s guide to the world’s sacred places. Olsen’s marvelous drawings and mysterious maps enhance a package that is as bizarre as it is wonderfully acces- sible. -

SOUTH WEST ENGLAND Frequently Asked Questions

SOUTH WEST ENGLAND Frequently Asked Questions Product Information & Key Contacts 2016 Frequently Asked Questions Bath Bath Visitor Information Centre Abbey Chambers Abbey Churchyard Bath BA1 1LY Key contact: Katie Sandercock Telephone: 01225 322 448 Email: [email protected] Website: www.visitbath.co.uk Lead product Nourished by natural hot springs, Bath is a UNESCO World Heritage city with stunning architecture, great shopping and iconic attractions. Rich in Roman and Georgian heritage, the city has been attracting visitors with its obvious charms for well over 2000 years and is now the leading Spa destination of the UK. Some of the highlights of the city include: The Roman Baths - constructed around 70 AD as a grand bathing and socialising complex. It is now one of the best preserved Roman remains in the world. Thermae Bath Spa – bathe in Bath’s natural thermal waters. Highlights include the indoor Minerva Bath, steam rooms, and an open-air rooftop pool with amazing views over the city. A fantastic range of treatments including massage, facials and water treatments can be booked in advance. Gainsborough Bath Spa Hotel – Britain’s first natural thermal spa hotel. Opened in July 2015. A five-star luxury hotel located in the centre of Bath. Facilities include 99 bedrooms (some with access to Bath’s spring water in their own bathrooms), The Spa Village Bath and Johan Lafer’s ‘Dining Without Borders’ restaurant. Bath Abbey - Magnificent stained glass windows, columns of honey-gold stone and some of the finest fan vaulting in the world, create an extraordinary experience of light and space. -

DORSET AMBASSADOR Promoting Dorset

LEARN MORE TODAY BECOME A DORSET AMBASSADOR Promoting Dorset Dorset has a stunning coastline, attractive rural landscapes, lively seaside resorts, fascinating towns and villages – all reasons for tourists to come here. This booklet gives you an overview of Dorset and some (not all!) of what visitors might ask about. Visitors to Dorset love to paint the scenery, visit art galleries, enjoy events and eat local food and drink. They like to explore hidden parts of Dorset on foot and see things that are different or unusual or lovely. They will want to experience Dorset’s culture; what makes Dorset a special place to be. They will pay to do so. They will tell other people about their amazing experiences; come back more often, and encourage others to come too. Want to expand and test your knowledge online? Go to www.dorsetambassador.co.uk and become a certified Dorset Ambassador! EXPLORE DORSET Portland Lighthouse Swanage Railway, Purbeck Poole Harbour West Bay The Brewery, Blandford Bournemouth Pier Hardy’s Cottage, West Dorset Kingston Lacy, East Dorset www.dorsetambassador.co.uk 4 NORTH DORSET What might visitors expect? Beautiful views, countryside walks, green fields and rolling downs. Gold Hill, pretty towns and villages, flowing rivers and watermills. Crafts, real ale, links to Somerset and Wiltshire. The main towns are Blandford Forum, Shaftesbury, Gillingham and Sturminster Newton. One of the most famous heritage landmarks in Dorset is Gold Hill in Shaftesbury, which is on the ‘must see’ list of many tourists – it even has its own museum! Pictures of Gold Hill are used all over the world to sell Dorset to tourists. -

South-Central England Regional Action Plan

Butterfly Conservation South-Central England Regional Action Plan This action plan was produced in response to the Action for Butterflies project funded by WWF, EN, SNH and CCW by Dr Andy Barker, Mike Fuller & Bill Shreeves August 2000 Registered Office of Butterfly Conservation: Manor Yard, East Lulworth, Wareham, Dorset, BH20 5QP. Registered in England No. 2206468 Registered Charity No. 254937. Executive Summary This document sets out the 'Action Plan' for butterflies, moths and their habitats in South- Central England (Dorset, Hampshire, Isle of Wight & Wiltshire), for the period 2000- 2010. It has been produced by the three Branches of Butterfly Conservation within the region, in consultation with various other governmental and non-governmental organisations. Some of the aims and objectives will undoubtedly be achieved during this period, but some of the more fundamental challenges may well take much longer, and will probably continue for several decades. The main conservation priorities identified for the region are as follows: a) Species Protection ! To arrest the decline of all butterfly and moth species in South-Central region, with special emphasis on the 15 high priority and 6 medium priority butterfly species and the 37 high priority and 96 medium priority macro-moths. ! To seek opportunities to extend breeding areas, and connectivity of breeding areas, of high and medium priority butterflies and moths. b) Surveys, Monitoring & Research ! To undertake ecological research on those species for which existing knowledge is inadequate. Aim to publish findings of research. ! To continue the high level of butterfly transect monitoring, and to develop a programme of survey work and monitoring for the high and medium priority moths. -

Dorset Places to Visit

Dorset Places to Visit What to See & Do in Dorset Cycling Cyclists will find the thousands of miles of winding hedge-lined lanes very enticing. Dorset offers the visitor a huge range of things to There is no better way to observe the life of the see and do within a relatively small area. What- countryside than on an ambling bike ride. The ever your interest, whether it be archaeology, more energetic cyclist will find a large variety of history, old churches and castles or nationally suggested routes in leaflets at the TICs. important formal gardens, it is here. Activities For people who prefer more organised Museums The county features a large number activities there is a wide range on offer, particu- of museums, from the world class Tank Museum larly in the vicinity of Poole, Bournemouth, to the tiniest specialist village heritage centre. All Christchurch and Weymouth. These cover are interesting and staffed by enthusiastic people everything expected of prime seaside resorts who love to tell the story of their museum. with things to do for every age and inclination. The National Trust maintains a variety of Coastline For many the prime attraction of properties here. These include Thomas Hardy’s Dorset is its coastline, with many superb beach- birthplace and his house in Dorchester. The es. Those at Poole, Bournemouth, Weymouth grandiose mansion of Kingston Lacy is the and Swanage have traditional seaside facilities creation of the Bankes family. Private man- and entertainments during the summer. People sions to visit include Athelhampton House and who prefer quiet coves or extensive beaches will Sherborne Castle. -

Wessex Branch Newsletter

The Open University Geological Society Wessex Branch Newsletter Website http://ougs.org/wessex July 2015 Branch Organiser’s Letter CONTENTS Branch Organiser’s Letter Page 1 Dear All Mendips weekend, 18-19 April 2015 Pages 2-6 I attended the OUGS AGM in Bristol in April and the Minerals guide no. 15 – Hydrozincite Page 6 Branch Organisers meeting in June. You will be Cerne Abbas, 10 May 2015 Pages 7-8 aware that there is a proposal that associate members of OUGS (ie those who have not studied or Cullernose Point, Northumberland Page 9 taught at OU), who pay the same fee as full Wessex Branch committee Page 9 members, should now be given the same rights (eg be able to vote at AGMs and hold posts on the Other organisations’ events Page 10 committee). The next OUGS Newsletter will include Forthcoming Wessex Branch events Page 11 different views about this. For your information, OUGS events listing Page 12 Wessex Branch has a number of very active and supportive associate members - as have other branches. Once you have had time to consider this October and November. Contact Jeremy if you would please let me know on [email protected] what you like to attend field trips on [email protected] think. I’m looking forward to our residential trip to Anglesey The other point of discussion was health and safety in September (waiting list only). Mark Barrett has on field trips. A good point was made by someone also booked our trip to Mull, 14th to 21st May 2016. who is an events organiser and also a geology leader Dr Ian Williamson is the leader. -

Crop Circle Formation II

Crop Circles Across the Universe By John Frederick Sweeney Abstract The British media once blamed two drunken pub crawlers for creating the annual crop circles which appear in the fields of south England, primarily around Wiltshire and the ancient henges, such as Stone Henge. Some posit UFO’s, some report balls of white light, even media companies have been known to inscribe fake crop circles. This paper presents the Vedic Science perspective on how Crop Circles are formed, theoretically from any other location in the Universe. Table of Contents Introduction 3 Vedic Physics Explanation 4 Discussion 5 Wikipedia on Silbury Hill 7 Chalk Figures 9 Conclusion 10 Appendix 12 Introduction Words are flowing out like endless rain into a paper cup, They slither while they pass, they slip away across the universe Pools of sorrow, waves of joy are drifting through my open mind, Possessing and caressing me. Jai guru de va om Nothing'sॐ gonna change my world, Nothing's gonna change my world. Vedic Physics posits that space is not empty, but instead filled with tiny unseen cubes that create space. Each of these spaces contains all the information of our entire holographic Universe, including the lyrics to the song John Lennon wrote for the Beatles. This condition implies that a rigid rod which extends across the universe can transmit and communicate across the universe, even so far as to inscribe Crop Circles in the rye fields of southern England. This paper explores the possibility that previous inhabitants of our Planet Earth may be among those who are inscribing geometrical designs in the countryside of southern England, amongst and between the henges and chalk figures, the White Horse and the neolithic ruins. -

The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles

www.RodnoVery.ru www.RodnoVery.ru The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles www.RodnoVery.ru Callanish Stone Circle Reproduced by kind permission of Fay Godwin www.RodnoVery.ru The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles Their Nature and Legacy RONALD HUTTON BLACKWELL Oxford UK & Cambridge USA www.RodnoVery.ru Copyright © R. B. Hutton, 1991, 1993 First published 1991 First published in paperback 1993 Reprinted 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998 Blackwell Publishers Ltd 108 Cowley Road Oxford 0X4 1JF, UK Blackwell Publishers Inc. 350 Main Street Maiden, Massachusetts 02148, USA All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Hutton, Ronald The pagan religions of the ancient British Isles: their nature and legacy / Ronald Hutton p. cm. ISBN 0-631-18946-7 (pbk) 1. -

7-Night Dorset Coast Walking with Sightseeing Holiday

7-Night Dorset Coast Walking with Sightseeing Holiday Tour Style: Walks with sightseeing Destinations: Dorset Coast & England Trip code: LHWOD-7 Trip Walking Grade: 2 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Take time to discover the landscape and heritage of the Dorset coast with this perfect mix of guided walks with sightseeing visits. Each holiday visits a selection of museums, historic buildings and attractions, whose entrance is optional. For 2021 holidays, please allow approximately £25 for admissions – less if you bring your English Heritage or National Trust cards. For 2022 holidays, all admissions to places of interest will be included in the price. That’s one less thing to remember! WHAT'S INCLUDED • Great value: all prices include Full Board en-suite accommodation, a full programme of walks with all transport to and from the walks, plus evening activities • Great walking: explore sections of the South West Coast Path, visit Corfe Castle and take a trip on the Swanage steam railway • Accommodation: our Country House is equipped with all the essentials – a welcoming bar and relaxing lounge area, a drying room for your boots and kit, heated outdoor swimming pool, and comfortable en- www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 suite rooms HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Walk on the Jurassic Coast to see the iconic Durdle Door • Visit the deserted village of Tyneham • Experience rural Dorset and view the ancient carved giant at Cerne Abbas • Visit the ruins of Corfe Castle, and ride the steam railway to the Victorian resort of Swanage TRIP SUITABILITY This trip is graded Activity Level 3, Walks are up to 5 miles (8km) and 850 feet (260m) of ascent. -

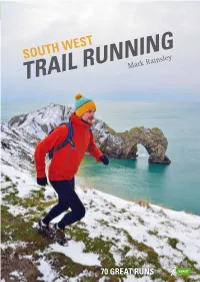

Trail Running

SOUTH WEST SOUTH WEST SOUTH WEST TRAIL RUNNING Mark Rainsley 70 routes for the off-road runner: these tried and tested TRAIL RUNNING paths and tracks cover the south-west of England, including the Isles of Scilly. Trail running is a great way to explore the South West and to immerse TRAIL yourself in its incredible landscapes. This guide is intended to inspire runners of all abilities to develop the skills and confidence to seek out new trails in their local areas as well as further afield. They are all great runs; selected for their runnability, landscape and scenery. The selection is deliberately diverse and is chosen to highlight the R incredible range of trail running adventures that the South West can UNNING offer. The runs are graded to help progressive development of the skills and confidence needed to tackle more challenging routes. TRAIL RUNNING FOR EVERYONE CLOSE TO TOWN & FAR AFIELD. Mark Rainsley ISBN 9781906095673 9 781906 095673 Front cover – Durdle Door Back cover – Porthcothan Bay www.pesdapress.com 70 GREAT RUNS h g old ou essex r W 65 wood W 64 g Downs the- Stow-on- Salisbury Swindon Rin North Marlbo 59 encester 63 The Bournemouth r 62 Plain 67 Ci Cotswolds 58 Salisbury ne 53 d 61 r r 52 Cheltenham 70 Distance Ascent Route Route Distance Ascent Route Route Poole Chase 51 Page Page WILTSHIRE 57 Cranbo 55 Forum (km) (m) No. Name Chippenham (km) (m) No. Name arminster 56 Blandfo 50 W 69 5.5 100 56 The Wardour Castles 265 13 425 48 Durdle Door 231 60 49 68 7 150 70 Cleeve Hill 325 48 13 425 51 St Alban’s Head 243 54 chester