The Origins, Functions, Control, and Ethical Implications of the Supermax Prison, 1976 - 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maureen Smith (612) 373-7507 Public Hearing on the Composition

UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA Vol. VIII No. 1 January 11, 1978 1\ ·vw:cl\iy intern::Ji bulictin serving all campuses Editor: Maureen Smith (612) 373-7507 Public hearing on the composition of a faculty collective bargaining unit on the TC campus will be the first agenda item at the regents' Committee of the Whole meeting Friday at 8:30a.m. in the regents' room, Morrill i~ll, Minneapolis. Anyone who wishes to appear is asked to call (612) 373-0080 and to prepare a written statement. Central question is whether the bargaining unit should include department heads, county extension agents, librarians, and others who may be classified as either faculty or management. Budget principles for 1978-79 and a report on capital requests before the legislature are also on the agenda. Physical Plant and Investments Committee will discuss purchasing procedures, energy conservation policy, and a proposed long-term lease for the West Bank People's Center, which is housed in aU-owned church building in mnneapolis. National tribute dinner for Sen. Hubert llumphrey Dec. 2 netted more than $1 million for the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. Total of $5.7 million that has now been raised includes $1 million each from businessmen Curtis Carlson and Dwayne Andreas and more than $3,000 in nickels and dimes from school children. Senate Consultative Committee will meet Jan. 12 at 12:30 p.m. in Room 625 in the Campus Club in Minneapolis. Other winter quarter meetings are scheduled for Feb. 2, Feb. 9 (on the Harris campus), and r.tarch 9. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Most Restrictive Alternative: The Origins, Functions, Control, and Ethical Implications of the Supermax Prison, 1976 - 2010 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5cj970ps Author Reiter, Keramet A. Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Most Restrictive Alternative: The Origins, Functions, Control, and Ethical Implications of the Supermax Prison, 1976 - 2010 By Keramet A. Reiter A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Jurisprudence and Social Policy in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Franklin E. Zimring, Chair Professor Jonathon Simon Professor Marianne Constable Professor David Sklansky Spring 2012 Abstract The Most Restrictive Alternative: The Origins, Functions, Control, and Ethical Implications of the Supermax Prison, 1976 - 2010 by Keramet A. Reiter Doctor of Philosophy in Jurisprudence and Social Policy University of California, Berkeley Professor Franklin E. Zimring, Chair Concrete, steel, artificial light, complete technological automation, near-complete sensory deprivation, and total isolation – these are the basic conditions of supermaximum security prisons in the United States. “Supermax” prisoners remain alone twenty-three to twenty-four hours a day, under fluorescent lights that are never turned off. Meals arrive through a small slot in an automated cell door. Prisoners have little to no human contact for months, years, or even decades at a time, save brief interactions with correctional officers, who place hand, ankle, and waist cuffs on each prisoner before removing him from his cell. -

Prison Law Reform in Japan: How the Bureaucracy Was Held to Account Over the Nagoya Prison Scandal

Volume 14 | Issue 5 | Number 4 | Article ID 4863 | Mar 01, 2016 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Prison Law Reform in Japan: How the Bureaucracy was Held to Account Over the Nagoya Prison Scandal Silvia Croydon Abstract: Japan's prison system is renowned Joy Hayms and Tom Murton, Accomplices for its safety and order. There has not been a to the Crime: Arkansas Prison Scandal, 1969 prison riot there in decades, and figures about escapes from and assaults at its penal facilities 'Japanese prisons are generally safe places with are far lower than in other developed nations. none of the violence or gang activity that the Such features have not gone unnoticed; foreign popular cinema associates with prison life in policy makers increasingly look to Japan for the [United States of America (USA)]', writes lessons in how to improve their own prisons. the American government on its Tōkyō Embassy website. Former American Senator Whilst various aspects of the Japanese prison Jim Webb, having visited Fuchū Prison in 1984 system have been investigated by legal experts, and talked to inmates there, holds the Japanese government agencies and human rights prison system in similarly high regard. His organizations, however, a gap remains with impression was that '[A]mericans familiar with respect to how Japanese prison policies are the horrors of Attica and New Mexico and the formulated. This article provides a study of the routine tales of brutality and homosexual rape decision-making process, focusing on the would find the orderly corridors of a Japanese political events triggered by a sequence of 2 prison mind-boggling' , and he has since keenly inmate injuries and fatalities in Nagoya Prison advocated that the US try to learn what it can following the turn of the century, which about prisons from Japan. -

FREE INQUIRY in CREATIVE SOCIOLOGY Volume 12, Number 1. May 1984 ISSN 0736

FREE INQUIRY IN CREATIVE SOCIOLOGY Volume 12, Number 1. May 1984 ISSN 0736 - 9182 Cover Design: Hobart Jackson, University of Kansas School of Architecture AUTHOR TABLE OF· CONTENTS PAGE Half-year Reviewers 2 Erratum Endo & Hirokawa Article. Vol 11, 1983. P 161 2 W Gruninger, N Hess Armed Robber Crime Patterns & Judicial Response 3 Robert Sigler Criminal Justice Evaluation Research & Theory Research 9 Ramona Ford CW Mills, Industrial Sociology, Worker Participation 13 Tom Murton The Penal Colony: Relic or Reform? 20 Laura D Birg Values of Fine Artists in an Independent Profession 25 Prakasa & Nandini Rao Perceived Consequences of ERA on Family & Jobs 30 Alan Woolfolk The Transgressive American: Decoding "Citizen Kane" 35 William E Thompson Oklahoma Old Order Amish: Adaptive Rural Tradition 39 Richard Peterson Preparing for Apocalypse: Survivalist Strategies 44 Janet Chafetz, Gary Dworkin Work Pressure: Homemaker Like Manager, Professional 47 David Field, Richard Travisano Social History & American Preoc cupation with Identity 51 Craig St John Trends in Socioeconomic Residential Segregtion 57 A Nesterenko, D Eckberg Attitudes to Tech-Science in a Bible Belt City 63 Karen Holmes, Paul Raffoul The Diagnostic Manual, DSM-III, & Social Work Practice 69 Barrie EM Blunt Motivation: Communication, Behavior Definition & Reward 73 P Sharp, G Acuff, R Dodder Oklahoma Delegate Traits: 1981 White House Aging Conf 75 Ann-Mari Sellerberg The Practical: Fashion's Latest Conquest 80 Gary Sandefur, Nancy Finley Manual-Nonmanual, Status Inconsistency, Social -

The Reel Prison Experience

SMU Law Review Volume 55 Issue 4 Article 7 2002 "Failure to Communicate" - The Reel Prison Experience Melvin Gutterman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Recommended Citation Melvin Gutterman, "Failure to Communicate" - The Reel Prison Experience, 55 SMU L. REV. 1515 (2002) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol55/iss4/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. "FAILURE To COMMUNICATE ' t THE REEL PRISON EXPERIENCE Melvin Gutterman* I. INTRODUCTION HE academic legal community has failed to appropriately recog- nize the images of law depicted by Hollywood as a legitimate and important subject for scholarly review.' Movies have the capacity to "open up" the discussion of contemporary legal issues that conven- tional legal sources ignore. 2 Although different from the normative legal theory of study, movies provide a rich portrait of popular jurisprudence of legal values.3 A fundamental paradox of many notable films is their inability to simultaneously achieve both scholastic acceptance and artistic achievement, at least equal to other media. 4 Movies are very powerful and can, through the use of provocative images, explore controversial themes and evoke passions that can affect even the most tightly closed minds. 5 The exclusion of films' celebrated images from academic study has its cost. There is, for example, a prevalent belief that life in prison is too t In the most celebrated colloquy in the movie Cool Hand Luke, the Captain as he stands over the defiant convict Luke asserts, "[w]hat we've got here is failure to communicate." What the Captain actually demands is that Luke totally capitulate to the contemptible prison system he embodies. -

Corrections in America an Introduction (15Th Edition)

Copyright Information (bibliographic) Document Type: Book Chapter Title of Book: Corrections in America An Introduction (15th Edition) Author(s) of Book: Harry E. Allen, Edward J. Latessa, Bruce S. Ponder Chapter Title: Chapter 2 Prisons (1800 to the Present) Author(s) of Chapter: Harry E. Allen, Edward J. Latessa, Bruce S. Ponder Year: 2019 Publisher: Pearson Education Place of Publishing: the United States of America The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specifies in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of fair use, that user may be liable for copyright infringement. Objectives • Summarize the definition, mission, and • Explain why the Auburn system became role of corrections from 1790 until 1910. the dominant prison design. • Compare and contrast the Pennsylvania • Describe prison development from the and Auburn systems. reformatory era to the modern era. Prisons (1800 to the Present) Outline To the builders What Is the Emerging Role of Corrections? of this nitemare The Pennsylvania System Though you may The Auburn System • Discipline at Auburn never get to read Prison Competition these words I pity Economics Wins Out you; For the cruelty Prison Rules of your minds have Change in the Wind designed this Hell; • Maconochie and Crofton: A New Approach If men's buildings • Maconochie and the Indeterminate Sentence are a reflection • Crofton and the Irish System of what they are, The Reformatory Era (1870-1910) This one portraits Post-Civil War Prisons the ugliness of all The Twentieth Century and the Industrial Prison humanity. -

A Rhetorical Study of Winthrop Rockefeller's Political Speeches, 1964-1971 (Arkansas)

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1984 A Rhetorical Study of Winthrop Rockefeller's Political Speeches, 1964-1971 (Arkansas). Merrill Anway Jones Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Jones, Merrill Anway, "A Rhetorical Study of Winthrop Rockefeller's Political Speeches, 1964-1971 (Arkansas)." (1984). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3959. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3959 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. -

Catalog Sixty-Nine Royalbooks C Atalog Sixty-Nine Royal Books the CELLULOID PAPER TRAIL

catalog catalog sixty-nine royal books Royalc Booksatalog sixty-nine THE CELLULOID PAPER TRAIL Oak Knoll Press is pleased to announce the publication of Terms and Conditions Kevin R. Johnson’s The Celluloid All books are first editions unless indicated otherwise. Paper Trail. The first book All items in wrappers or without dust jackets advertised have glassine covers, and all dust jackets are protected ever published on film script by new archival covers. Single, unframed photographs identification and description, housed in new, archival mats. lavishly illustrated and detailed. In many cases, more detailed physical descriptions for archives, manuscripts, film scripts, and other ephemeral Designed for any book scholar, items can be found on our website. including collectors, archivists, Any item is returnable within 30 days for a full refund. librarians, and dealers. Books may be reserved by telephone, or email, and are subject to prior sale. Payment can be made by credit card Available now at royalbooks.com or, if preferred, by check or money order with an invoice. or by calling 410.366.7329. Libraries and institutions may be billed according to preference. Reciprocal courtesies extended to dealers. Please feel free to let us know if you would like your copy signed or inscribed by the author. We accept credit card payments by VISA, MASTERCARD, AMERICAN EXPRESS, DISCOVER, and PAYPAL. Shipments are made via USPS priority mail or Fedex Ground unless other arrangements are requested. All shipments are fully insured. Shipping is free within the United States. For international destinations, shipping is $60 for the first book and $10 for each thereafter. -

90357NCJRS.Pdf

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. • "17'~ • , 4 t f \: CI?.,k.. '1 ..f' " il 10'" :;)I-f' j lr ~ l National Criminal Justice Reference Service " ~; This microfiche was produced from documents received for inclusion in the NCJRS data base. Since NCJRS cannot exercise control over the physical condition of the documents submitted, STATE OF IOWA the individual frame quality will vary. The resolution chart on this frame may be used to evaluate the document quality. DEP~TMENT OF SOCIAL SERVICES Division of Adult Corrections (, 1 Harold A. Farrier, Director \ 1.0 1 i· \, 1.1 PRISONS ANq KIDS --- ---J 111111.25 111111.4 111111.6 j 'I I -/' MICROCOPY RESOLUTIVN TEST CHART j i' NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANOARDS·1963.A !! '( l \ I, , ,! • fl \ l~, ~ i II .J Microfilmir 9 procedures used to create this fiche comply with James Boudouris Ph D the standards set forth in 41CFR 101-11.504. i· Correctional E '1 -,- i' Division of Ad~f uat10n P70gram Director Hoover Build' t Correct1ons Points of view or opinions stated in this document are 1ng, 5th floor i 1 those of the author(s) and do not r~present the official l June, 1983 I position or policies of the U. S. Department of Justice. National Institute of JustiGe United States Department of Justice Washington. D, C, 20531 o , ..-- ... $ 4 1 \ I ~ \1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY I) r This report is a survey of programs for incarcerated , ~ mothers and their children in SS correctional institutions ~I in alISO states, representing a total population of 14,610 ·f) \, women. -

Via Issuelab

ROCKEFELLER ARCHIVE CENTER RESEARCH REPORTS Health-Related Prison Conditions in the Progressive and Civil Rights Eras: Lessons from the Rockefeller Archive Center by Jessica L. Adler Florida International University © 2020 by Jessica L. Adler Abstract During my 2019 visit to the Rockefeller Archive Center (RAC), I viewed papers from more than a dozen collections, which provided perspective on how health, incarceration, politics, and policy intermingled in the twentieth century. In this report, I offer an overview of my book project, Minimal Standards of Adequacy: A History of Health Care in Modern U.S. Prisons, and analyze how portions of it will be informed by two sets of documents from the RAC. I focus first on records contained in the Bureau of Social Hygiene records, which shed light on the perspectives of Progressive Era penologists who helped to shape ideals and practices related to prison health in specific institutions, as well as in state and federal correctional systems. Next, I discuss findings from the papers of Winthrop Rockefeller, who served as governor of Arkansas from 1966 to 1970, when federal courts deemed conditions within the state’s prison system unconstitutional. While I continue to undertake research for the book, this report serves as a snapshot of my current reading of select sources from two different moments in the history of US prisons. It suggests the extent to which, throughout the twentieth century, carceral institutions posed tremendous health threats to the increasing numbers of people inside them, even as radical advocates urged drastic change, and as reformers, corrections professionals, and political representatives called for more rules, regulations, and bureaucracy. -

The Reel Prison Experience Melvin Gutterman

SMU Law Review Volume 55 | Issue 4 Article 7 2002 "Failure to Communicate" - The Reel Prison Experience Melvin Gutterman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Recommended Citation Melvin Gutterman, "Failure to Communicate" - The Reel Prison Experience, 55 SMU L. Rev. 1515 (2002) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol55/iss4/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. "FAILURE To COMMUNICATE ' t THE REEL PRISON EXPERIENCE Melvin Gutterman* I. INTRODUCTION HE academic legal community has failed to appropriately recog- nize the images of law depicted by Hollywood as a legitimate and important subject for scholarly review.' Movies have the capacity to "open up" the discussion of contemporary legal issues that conven- tional legal sources ignore. 2 Although different from the normative legal theory of study, movies provide a rich portrait of popular jurisprudence of legal values.3 A fundamental paradox of many notable films is their inability to simultaneously achieve both scholastic acceptance and artistic achievement, at least equal to other media. 4 Movies are very powerful and can, through the use of provocative images, explore controversial themes and evoke passions that can affect even the most tightly closed minds. 5 The exclusion of films' celebrated images from academic study has its cost. There is, for example, a prevalent belief that life in prison is too t In the most celebrated colloquy in the movie Cool Hand Luke, the Captain as he stands over the defiant convict Luke asserts, "[w]hat we've got here is failure to communicate." What the Captain actually demands is that Luke totally capitulate to the contemptible prison system he embodies. -

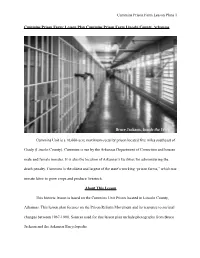

Cummins Unit Is a 16,600-Acre Maximum-Security Prison Located Five Miles Southeast Of

Cummins Prison Farm Lesson Plans !1 Cummins Prison Farm: Lesson Plan Cummins Prison Farm Lincoln County, Arkansas Bruce Jackson, Inside the Wire Cummins Unit is a 16,600-acre maximum-security prison located five miles southeast of Grady (Lincoln County). Cummins is run by the Arkansas Department of Correction and houses male and female inmates. It is also the location of Arkansas’s facilities for administering the death penalty. Cummins is the oldest and largest of the state’s working “prison farms,” which use inmate labor to grow crops and produce livestock. About This Lesson This historic lesson is based on the Cummins Unit Prison located in Lincoln County, Arkansas. This lesson plan focuses on the Prison Reform Movement and its response to societal changes between 1967-1990. Sources used for this lesson plan include photographs from Bruce Jackson and the Arkansas Encyclopedia. Cummins Prison Farm Lesson Plans !2 Topics: The lesson could be used in Arkansas History, Criminal Justice, Sociology, Psychology, Statistical Methods, or General Mathematic courses. Time Period: 1967-1990s Topics to Visit/Expand Upon: Social Studies, Criminal Justice, Government and Politics, Sociology, Psychology, and General Mathematics. Objectives for Students 1. Students will explore the physical design of Cummins Unit and how the design changed throughout the years. 2. Students will give reasons why Cummins Unit deviated from the Arkansas System in the early 1900s. 3. Students will develop an understanding of the internal and external factors that caused changes within the penitentiary. 4. Students will analyze the crimes of the inmates and determine how those crimes represent or reflect the society outside of Cummins Unit.