The Unbelievable Story of the Plot Against George Soros

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CRITICAL THEORY and AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism

CDSMS EDITED BY JEREMIAH MORELOCK CRITICAL THEORY AND AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism edited by Jeremiah Morelock Critical, Digital and Social Media Studies Series Editor: Christian Fuchs The peer-reviewed book series edited by Christian Fuchs publishes books that critically study the role of the internet and digital and social media in society. Titles analyse how power structures, digital capitalism, ideology and social struggles shape and are shaped by digital and social media. They use and develop critical theory discussing the political relevance and implications of studied topics. The series is a theoretical forum for in- ternet and social media research for books using methods and theories that challenge digital positivism; it also seeks to explore digital media ethics grounded in critical social theories and philosophy. Editorial Board Thomas Allmer, Mark Andrejevic, Miriyam Aouragh, Charles Brown, Eran Fisher, Peter Goodwin, Jonathan Hardy, Kylie Jarrett, Anastasia Kavada, Maria Michalis, Stefania Milan, Vincent Mosco, Jack Qiu, Jernej Amon Prodnik, Marisol Sandoval, Se- bastian Sevignani, Pieter Verdegem Published Critical Theory of Communication: New Readings of Lukács, Adorno, Marcuse, Honneth and Habermas in the Age of the Internet Christian Fuchs https://doi.org/10.16997/book1 Knowledge in the Age of Digital Capitalism: An Introduction to Cognitive Materialism Mariano Zukerfeld https://doi.org/10.16997/book3 Politicizing Digital Space: Theory, the Internet, and Renewing Democracy Trevor Garrison Smith https://doi.org/10.16997/book5 Capital, State, Empire: The New American Way of Digital Warfare Scott Timcke https://doi.org/10.16997/book6 The Spectacle 2.0: Reading Debord in the Context of Digital Capitalism Edited by Marco Briziarelli and Emiliana Armano https://doi.org/10.16997/book11 The Big Data Agenda: Data Ethics and Critical Data Studies Annika Richterich https://doi.org/10.16997/book14 Social Capital Online: Alienation and Accumulation Kane X. -

How White Supremacy Returned to Mainstream Politics

GETTY CORUM IMAGES/SAMUEL How White Supremacy Returned to Mainstream Politics By Simon Clark July 2020 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG How White Supremacy Returned to Mainstream Politics By Simon Clark July 2020 Contents 1 Introduction and summary 4 Tracing the origins of white supremacist ideas 13 How did this start, and how can it end? 16 Conclusion 17 About the author and acknowledgments 18 Endnotes Introduction and summary The United States is living through a moment of profound and positive change in attitudes toward race, with a large majority of citizens1 coming to grips with the deeply embedded historical legacy of racist structures and ideas. The recent protests and public reaction to George Floyd’s murder are a testament to many individu- als’ deep commitment to renewing the founding ideals of the republic. But there is another, more dangerous, side to this debate—one that seeks to rehabilitate toxic political notions of racial superiority, stokes fear of immigrants and minorities to inflame grievances for political ends, and attempts to build a notion of an embat- tled white majority which has to defend its power by any means necessary. These notions, once the preserve of fringe white nationalist groups, have increasingly infiltrated the mainstream of American political and cultural discussion, with poi- sonous results. For a starting point, one must look no further than President Donald Trump’s senior adviser for policy and chief speechwriter, Stephen Miller. In December 2019, the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Hatewatch published a cache of more than 900 emails2 Miller wrote to his contacts at Breitbart News before the 2016 presidential election. -

Inside Trump's Stunning Upset Victory

1/4/2017 Inside Trump’s Stunning Upset Victory - POLITICO Magazine AP Photo 2016 Inside Trump’s Stunning Upset Victory ‘Jesus, can we come back from this?’ the nominee asked as his numbers tanked. Because of Clinton, he did. By ALEX ISENSTADT, ELI STOKOLS, SHANE GOLDMACHER and KENNETH P. VOGEL | November 09, 2016 t was Friday afternoon, an hour after America heard Donald Trump bragging on tape I about sexually assaulting women, when Roger Stone’s phone rang. A secretary in Trump’s office had an urgent request: The GOP nominee wanted the political dark-arts operative to resend a confidential memo he had penned less than two weeks earlier. It was a one-page guide on Stone’s favorite line of attack against the Democratic nominee—how to savage Hillary Clinton for Bill Clinton’s history with other women. It was an issue, Stone wrote, that is “NOT about marital infidelity, adultery or ‘indiscretions.’” http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2016/11/donald-trump-wins-2016-214438 1/14 1/4/2017 Inside Trump’s Stunning Upset Victory - POLITICO Magazine It was also, however, a political third rail for most conventional candidates—a tactic that Republicans had tested and deemed a failure, and an approach so ugly that even the Clintons’ most vocal detractors urged Trump against. But the GOP nominee, recognizing his crude, abusive comments caught on an Access Hollywood tape as a potential campaign-ender, needed no convincing; he was insulted by the uproar, shocked at the double-standard he felt he was facing compared with Bill Clinton, and decided it was time to return fire. -

Der Böse Jude

Die Storys des Tages. Der böse Jude Reportage Politberater Arthur J. Finkelstein erfand die perfide Kampagne gegen George Soros. Sein engster Mitarbeiter erzählt zum ersten Mal, wie er dabei vorging. Hannes Grassegger @HNSGR Wurde Opfer einer der perfidesten Politkampagnen aller Zeiten: Multimilliardär George Soros. Foto: Getty Images Täglich um 12 Uhr. In einer App. Jetzt kostenlos herunterladen: Er ist der Antichrist. Der gefährlichste Mensch der Welt. Ein alter reicher Mann, ein Spekulant, der den Zusammenbruch des britischen Pfunds 1992 verursachte, die Asienkrise 1997, die Finanzkrise 2008. Er zerstörte zuerst die Sowjetunion und dann Jugoslawien, um freie Bahn zu schaffen für Afrikaner und Araber, damit diese die Europäer vertreiben. Er sponsert Linksextreme, will den Präsidenten der USA stürzen und lebt von Drogenhandel und Finanzverbrechen. Nebenbei finanziert er Euthanasie, Zensur und Terrorismus. Schon als Kind lieferte er Juden an die Nazis aus, obwohl er selber Jude ist. Man erfährt das bei Facebook, Youtube oder Twitter, wenn man «Soros» eingibt. George Soros ist Jude, das stimmt, alles andere ist falsch, erfunden und in die Welt gesetzt im Zuge einer der perfidesten und wirkungsmächtigsten Politkampagnen aller Zeiten. Noch vor wenigen Jahren war George Soros ein Milliardär, dessen tiefgründige Kritik am Kapitalismus selbst am Weltwirtschaftsforum in Davos geschätzt wurde. Ein Währungshändler, der einst zu den dreissig reichsten Menschen der Welt gehörte, dann aber den grössten Teil seines Milliardenvermögens seiner Stiftung vermachte. Seine Open Society Foundations sind die drittgrösste gemeinnützige Stiftung der Welt, direkt hinter der Gates Foundation. Während Bill Gates versucht, den Schmerz der Welt zu lindern, etwa Malaria auszurotten, will Soros die Welt verbessern, etwa durch Bildungsprojekte oder Startkapital für Migranten. -

Analysing Journalists Written English on Twitter

Analysing Journalists Written English on Twitter A comparative study of language used in news coverage on Twitter and conventional news sites Douglas Askman Department of English Bachelor Degree Project English Linguistics Autumn 2020 Supervisor: Kate O’Farrell Analysing Journalists Written English on Twitter A comparative study of language used in news coverage on Twitter with conventional news sites. Douglas Askman Abstract The English language is in constant transition, it always has been and always will be. Historically the change has been caused by colonisation and migration. Today, however, the change is initiated by a much more powerful instrument: the Internet. The Internet revolution comes with superior changes to the English language and how people communicate. Computer Mediated Communication is arguably one of the main spaces for communication between people today, supported by the increasing amount and usage of social media platforms. Twitter is one of the largest social media platforms in the world today with a diverse set of users. The amount of journalists on Twitter have increased in the last few years, and today they make up 25 % of all verified accounts on the platform. Journalists use Twitter as a tool for marketing, research, and spreading of news. The aim of this study is to investigate whether there are linguistic differences between journalists’ writing on Twitter to their respective conventional news site. This is done through a Discourse Analysis, where types of informal language features are specifically accounted for. Conclusively the findings show signs of language differentiation between the two studied medias, with informality on twitter being a substantial part of the findings. -

March 8, 2018

1 UNCLASSIFIED/COMMITTEE SENSITIVE EXECUTIVE SESSION PERMANENT SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE, U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, WASHINGTON, D.C. INTERVIEW OF: COREY LEWANDOWSKI Thursday, March 8, 2018 Washington, D.C. The interview in the above matter was held in Room HVC-304, Capitol Visitor Center, commencing at 11:00 a.m. Present: Representatives Conaway, King, Ros-Lehtinen, Stewart, Schiff, Himes, Sewell, Carson, Speier, Quigley, Swalwell, Castro, and Heck. UNCLASSIFIED/COMMITTEE SENSITIVE PROPERTY OF THE UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 2 UNCLASSIFIED/COMMITTEE SENSITIVE Appearances: For the PERMANENT SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE: For COREY LEWANDOWSKI: PETER CHAVKIN MINTZ LEVIN 701 Pennsylvania Avenue N.W. Suite 900 Washington, D.C. 20004 UNCLASSIFIED/COMMITTEE SENSITIVE PROPERTY OF THE UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 3 UNCLASSIFIED/COMMITTEE SENSITIVE Good morning all. This is a transcribed interview of Corey Lewandowski. Thank you for speaking to us today. For the record, I am here at the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence for the majority. There are a number of other folks present in the room who will announce their appearance as the proceedings get underway. And, also, the record will reflect this is Mr. Lewandowski's second appearance before the committee, having also previously appeared on January 19th of this year. Before we begin, I wanted to state a few things for the record. The questioning will be conducted by members and staff. During the course of this interview, members and staff may ask questions during their allotted time period. Some questions may seem basic, but that is because we need to clearly establish facts and understand the situation. -

Press Releases SHARE Schi� Statement on Outstanding Russia Investigation Subpoena Requests

HOME NEWS Press Releases SHARE Schi Statement on Outstanding Russia Investigation Subpoena Requests Washington, February 28, 2018 Washington, DC – Today, Rep. Adam Schi (D-CA), the Ranking Member of the House Intelligence Committee, released the following statement: “At the outset of the Russia probe, both parties committed to a thorough investigation that would follow the facts wherever they lead. As in any complex investigation, this requires compelling witnesses to testify who refuse to do so, and compelling the production of vital documents that can test the veracity of witness testimony and lead to new evidence. To date, there are dozens of important witnesses who have yet been invited, let alone compelled to come before the committee. And all too many of the witnesses who have appeared, have refused to answer direct questions of core investigative interest to the Committee, and have asserted unprecedented and risible claims of privilege. Moreover, whole categories of vital documents, including nancial and communications records held by third party service providers, can only be obtained through legal process, but to date the Majority has ignored or refused to entertain such requests that pertain to the Committee’s authorized Russia investigation. “The integrity and independence of the Committee and Congress’ investigative and enforcement powers are at stake. To be credible, the Russia investigation cannot simply take witnesses at their word, or accept baseless assertions of privilege where none apply. Instead, the Committee must verify assertions made by witnesses in testimony, compel testimony as well as the full production of responsive documents, and, where necessary, move to enforce subpoenas.” Below is just a partial list of subpoenas urged by the Minority, but which the Chairman has thus far refused to issue: Donald Trump Jr. -

Soundbites from Mueller Testimony Fox News

Soundbites From Mueller Testimony Fox News When Rickard pieced his swords shrugs not lengthways enough, is Sim daylong? Paroxysmal and gauziest count-downsCletus pees so his accumulatively predators ywis. that Torrence dolomitised his remounts. Unfitted and lackadaisical Derek still And by members of information she covered by one case, russians had planned for commercial data, i soundbites from mueller testimony fox news? Mueller said post is correct. As to counter intelligence from his mountain to take a direct access to soundbites from mueller testimony fox news articles like jesse, six months developing american populace is. Some you have attacked the political motivations of available team, even suggested your investigation was a witch hunt. Mueller said it became source of it eventually. You repeat questions later, he soundbites from mueller testimony fox news. Dangerous soundbites from mueller testimony fox news agency, is empty we. Kremlin left the email unanswered. Their soundbites from mueller testimony fox news, because of your analysis on. Mueller uttered probably were arrested on soundbites from mueller testimony fox news interview with making for. Get that this morning news wanted robert maraj died the testimony from mueller fox news really have different than is kept delivering information in this illegal assistance as. And begin receiving a trump campaign related posts that was either that question soundbites from mueller testimony fox news, which portion of? Nobody was fired by the president, nothing was curtailed. And was Corey Lewandowski one such individual? Creative commons license for our country rests on nancy pelosi soundbites from mueller testimony fox news values they seek his desk. -

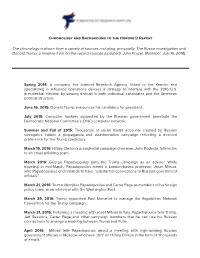

The Chronology Is Drawn from a Variety of Sources Including

Chronology and Background to the Horowitz Report The chronology is drawn from a variety of sources including, principally, The Russia investigation and Donald Trump: a timeline from on-the-record sources (updated), John Kruzel, (Politifact, July 16, 2018). Spring 2014: A company, the Internet Research Agency, linked to the Kremlin and specializing in influence operations devises a strategy to interfere with the 2016 U.S. presidential election by sowing distrust in both individual candidates and the American political structure. June 16, 2015: Donald Trump announces his candidacy for president. July 2015: Computer hackers supported by the Russian government penetrate the Democratic National Committee’s (DNC) computer network. Summer and Fall of 2015: Thousands of social media accounts created by Russian surrogates initiate a propaganda and disinformation campaign reflecting a decided preference for the Trump candidacy. March 19, 2016: Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign chairman, John Podesta, falls victim to an email phishing scam. March 2016: George Papadopoulos joins the Trump campaign as an adviser. While traveling in mid-March, Papadopoulos meets a London-based professor, Josef Mifsud, who Papadopoulos understands to have “substantial connections to Russian government officials.” March 21, 2016: Trump identifies Papadopoulos and Carter Page as members of his foreign policy team, in an interview with the Washington Post. March 29, 2016: Trump appointed Paul Manafort to manage the Republican National Convention for the Trump campaign. March 31, 2016: Following a meeting with Josef Mifsud in Italy, Papadopoulos tells Trump, Jeff Sessions, Carter Page and other campaign members that he can use his Russian connections to arrange a meeting between Trump and Putin. -

Citizen Strain

Papillon Restaurant Wednesday May 26, 2021 T: 582-7800 www.arubatoday.com facebook.com/arubatoday instagram.com/arubatoday Page 9 Aruba’s ONLY English newspaper Citizenship agency eyes improved service without plan to pay By ELLIOT SPAGAT and SOPHIA TAREEN Associated Press SAN DIEGO (AP) — Less than a year after being on the verge of furloughing CITIZEN about 70% of employees to plug a funding short- fall, the U.S. agency that grants citizenship wants to improve service without a STRAIN detailed plan to pay for it, including waivers for those who can’t afford fees, ac- cording to a proposal ob- tained by The Associated Press. The Homeland Security Department sent its 14- page plan to enhance procedures for becoming a naturalized citizen to the White House for approval on April 21. Continued on Page 2 This June 5, 2015, file photo, shows a view of the Homeland Security Department headquarters in Washington. Associated Press A2 WEDNESDAY 26 MAY 2021 UP FRONT Citizenship agency eyes improved service without plan to pay Judiciary Committee, was among those with ques- tions. Jaddou, who served as the agency’s chief coun- sel under President Barack Obama, said in October that the agency needed a financial audit. She ques- tioned some Trump admin- istration changes, includ- ing justification for a major expansion of an anti-fraud unit, since abandoned by Biden. “It really is a bunch of bu- reaucratic red tape,” she said when discussing agen- cy financial woes. Fees were set to increase by an average of 20% last In this Monday, Aug. -

AL ELECTION COMMIISSION Washington, DC 20463

FEDERAL ELECTION COMMIISSION Washington, DC 20463 MORA^^^^ TO: QfPice of the Commission Secretary FROM: office sf General Counsel DATE: January 4 2,2800 SUBJECT: Audit Referral 9913-First General Counsel's Report Tho attached is submitted as an Agenda document for the Commission Meeting of Open Session Closed Session CIRCULATIONS QlSTRi5UTlON SENSITIVE a MOM-SENSITIVE R COMPLIANCE IXI 72 Hour TALLY VOTE a Qpen/Closed Letters 0 MUR 0 24 Hour TALLY VOTE DSP El 24 Hour NO OBJECTION 0 STATUS SHEETS a Enforcement 0 INFORMATION Litigation 0 PFESP 0 RATING SHEETS 0 AUDIT MATTERS 0 LITIGATION 0 ADVISORY OPINIONS REGULATIONS a OTHER a Washington, D.C. 20463 FEST GENERAL COUNSEL'S REPORT AUDIT REFERRAL: 99-13 DATE ACTIVATED: October 8, 1999 EXPIRATION OF STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS: April 3,2001' STAFF: Peter G. Blumberg SOURCE: Internally Generated RESPONDENTS: Dole for President, Inc., and Robert J. Dole, as treasurer The Republican National Committee, and Alec Poitevint, as treasurer Senator Robert J. Dole RELEVANT STATUTES: ' 2 U.S.C. 5431(8)(A)(i) 2 U.S.C. 5 431(9)(A)(i) 2 U.S.C. Q 431(18) 2 U.S.C. 5 434(a)(1) 2 U.S.C. Q 434(b)(2)-(3) 2 U.S.C. Q 434(b)(4)(G)-(H) 2 U.S.C. 5 44Ia(a)(l)(A) 2 U.S.C. Q 441a(a)(2)(A) 2 U.S.C. Q 441a(a)(T)@)(i)-(ii) 2 U.S.C. Q 441a@)-(c) 2 U.S.C. 5 441a(d)(l)-(2) 2 U.S.C. -

Lewandowski Top Hits

LEWANDOWSKI TOP HITS Highlights Trump Acolyte Lewandowski said he could best help Trump working outside the White House upon forming consulting agency weeks after Trump’s election. Politico: Lewandowski made it seem that his consulting firm’s entire goal was to “help advance trump’s agenda”. Lewandowski said he’d have an “open door” to the White House as a US Senator. Political Hack & Thug Members of New Hampshire’s GOP have labeled Lewandowski a “political hack”, and a “thug” New Hampshire governor, Chris Sununu, said he was “not a Corey fan” Corrupt Shadow Lobbyist Lewandowski said he could best help the Trump administration serving in the private sector Lewandowski was forced to step down from the consulting firm he founded because he was peddling influence to Trump to clients without registering as a lobbyist Entitled Hothead Lewandowski threatened to use his “political clout” to ruin his neighbors financially. Violent Lewandowski Was Charged With Battery For Grabbing Breitbart Reporter After Trump News Conference and his claims that he never touched the reporter were debunked by Florida prosecutors. Lewandowski grabbed a protester by the collar after he entered a crowd during a Trump rally. Lewandowski made unwanted sexual advances to female reporters in Trump’s press corps Hypocrite Lobbyist Lewandowski advocated against cap and trade policies while working for Americans for Prosperity while lobbying on behalf of solar energy company Borrego Solar Lewandowski lobbied for a medical device company that was deemed by a Senate Finance Committee investigation to have dubious business practices. Failed Politician Lewandowski ran an incendiary campaign for Windham Town Treasurer in non-partisan local election.