Narsingrao Gurunath Patil and Ors. Vs. Arun

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Davr\Vc `Fded "% ^`Cv >=2D

' !! ; # < << .&/.%0 123+ )+,+),- ()#* % )#. / # 2 %.7 .3 #=$.%7 2.7 7 ,117 7/7 ./7 7$9. $,%(3=8 19=# $ 19,1 378 1,$$7 9=3 (=3 #= 7 7 3%9. .#, %9 3. 9 9, 3. : 97 #7# $( 79 ,3 9:7 1 /.& :8 $ % - >* ..% 45? @ 7 4 ! *54 *,156 13 * Q ( / R - 173 $,, surised mentally as Speaker to deal with all these things, I am arnataka Assembly Speaker pushed into a sea of depres- KKR Ramesh disqualified sion,” said an emotional Kumar. R 14 rebel MLAs of the Congress The disqualified MLAs are: and Janata Dal (S) on Sunday Pratap Gowda Patil, BC Patil, — a day before Chief Minister Shivram Hebbar, ST BS Yediyurappa will see trust Somashekar, Byrati Basavaraj, vote in the House. Anand Singh, Roshan Baig, Confident about proving Munirathna, K Sudhakar and the majority, Yediyurappa said MTB Nagaraj and Shrimant 378 7$9. the Finance Bill prepared by the Patil (all Congress). Other previous Congress-JD(S) party MLAs Ramesh Jarkiholi, fter deploying 10,000 addi- Government would be tabled Mahesh Kumatalli and Shankar Ational jawans in the by him in the Assembly on were disqualified on Thursday. Kashmir Valley, which was Monday, without any changes. JD(S) members who faced reportedly in repose to intelli- The Speaker disqualified action are Gopalaiah, AH gence inputs about terror threat held extensive talks with top for Assembly elections when- 11 Congress MLAs and three Vishwanath and Narayana from across the border, the officials of the counter securi- ever they are held. The likely JD(S) MLAs under the anti- Gowda. -

IDL-56493.Pdf

Changes, Continuities, Contestations:Tracing the contours of the Kamathipura's precarious durability through livelihood practices and redevelopment efforts People, Places and Infrastructure: Countering urban violence and promoting justice in Mumbai, Rio, and Durban Ratoola Kundu Shivani Satija Maps: Nisha Kundar March 25, 2016 Centre for Urban Policy and Governance School of Habitat Studies Tata Institute of Social Sciences This work was carried out with financial support from the UK Government's Department for International Development and the International Development Research Centre, Canada. The opinions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect those of DFID or IDRC. iv Acknowledgments We are grateful for the support and guidance of many people and the resources of different institutions, and in particular our respondents from the field, whose patience, encouragement and valuable insights were critical to our case study, both at the level of the research as well as analysis. Ms. Preeti Patkar and Mr. Prakash Reddy offered important information on the local and political history of Kamathipura that was critical in understanding the context of our site. Their deep knowledge of the neighbourhood and the rest of the city helped locate Kamathipura. We appreciate their insights of Mr. Sanjay Kadam, a long term resident of Siddharth Nagar, who provided rich history of the livelihoods and use of space, as well as the local political history of the neighbourhood. Ms. Nirmala Thakur, who has been working on building awareness among sex workers around sexual health and empowerment for over 15 years played a pivotal role in the research by facilitating entry inside brothels and arranging meetings with sex workers, managers and madams. -

Modification of the High Court Cision.' Haryana Will Go to Polls on Oc- a Decision

If a man achieves victory over this THURSDAY body, who in the world can OCTOBER 17, 2019 exercise power over him? He who CHANDIGARH rules himself rules over the whole VOL. XXIII, NO. 248 world. PAGES 12 Rs. 2 Vinoba Bhave YUGMARGYOUR REGION, YOUR PAPER Sultan of Johor Cup: India Corruption increased whenever Bhumi shares her first look defeat Australia 5-1 Congress came to power: Shah from'Pati Patni Aur Woh' ...PAGE 10 ...PAGE 12 .... PAGE 3 Ayodhya land dispute: Arguments concluded, SC reserves verdict Three LeT militants killed in Anantnag Judgement likely to be pronounced in 2nd week of Nov encounter ANANTNAG: Three Lashkar-e- AGENCY Drama during Taiba (LeT) militants were killed NEW DELHI, OCT 16 by security forces in an en- hearing on 40th day counter which ensued during a The Supreme Court on Thursday NEW DELHI: Tempers rose in- Cordon and Search Operation reserved its verdict on a batch of side the Supreme Court cham- Jolt to Cong, Tanwar (CASO) in this south Kashmir petitions in connection with the bers on Wednesday—the final district on Wednesday, official Ram Mandir-Babri Masjid land day of hearing in the Ayodhya ti- sources said. dispute case. tle dispute case, as the Muslim This is the first CASO launched The five-judge Constitution side tore into shreds a document by the security forces in Kashmir extends support to JJP submitted by the Hindu side, valley after post-paid mobile bench of the Supreme Court, headed by Chief Justice of India right in front of the five-judge phones were restored on Mon- bench headed by Chief Justice day noon after remaining sus- Ranjan Gogoi, today reserved its AGENCY nounced on October 24. -

Maharashtra Vidhan Sabha Candidate List.Xlsx

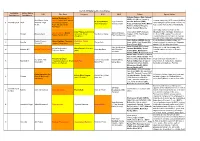

List of All Maharashtra Candidates Lok Sabha Vidhan Sabha BJP Shiv Sena Congress NCP MNS Others Special Notes Constituency Constituency Vishram Padam, (Raju Jaiswal) Aaditya Thackeray (Sunil (BSP), Adv. Mitesh Varshney, Sunil Rane, Smita Shinde, Sachin Ahir, Ashish Coastal road (kolis), BDD chawls (MHADA Dr. Suresh Mane Vijay Kudtarkar, Gautam Gaikwad (VBA), 1 Mumbai South Worli Ambekar, Arjun Chemburkar, Kishori rules changed to allow forced eviction), No (Kiran Pawaskar) Sanjay Jamdar Prateep Hawaldar (PJP), Milind Meghe Pednekar, Snehalata ICU nearby, Markets for selling products. Kamble (National Peoples Ambekar) Party), Santosh Bansode Sewri Jetty construction as it is in a Uday Phanasekar (Manoj Vijay Jadhav (BSP), Narayan dicapitated state, Shortage of doctors at Ajay Choudhary (Dagdu Santosh Nalaode, 2 Shivadi Shalaka Salvi Jamsutkar, Smita Nandkumar Katkar Ghagare (CPI), Chandrakant the Sewri GTB hospital, Protection of Sakpal, Sachin Ahir) Bala Nandgaonkar Choudhari) Desai (CPI) coastal habitat and flamingo's in the area, Mumbai Trans Harbor Link construction. Waris Pathan (AIMIM), Geeta Illegal buildings, building collapses in Madhu Chavan, Yamini Jadhav (Yashwant Madhukar Chavan 3 Byculla Sanjay Naik Gawli (ABS), Rais Shaikh (SP), chawls, protests by residents of Nagpada Shaina NC Jadhav, Sachin Ahir) (Anna) Pravin Pawar (BSP) against BMC building demolitions Abhat Kathale (NYP), Arjun Adv. Archit Jaykar, Swing vote, residents unhappy with Arvind Dudhwadkar, Heera Devasi (Susieben Jadhav (BHAMPA), Vishal 4 Malabar Hill Mangal -

'Dnl\D Gdn Od\D Qrz Zloo Jhw Jrrg Prqh\

" $ VRGR '%&((!1#VCEB R BP A"'!#$#1!$"#0$"T utqVQWBuxy( 12!314 *56+ '&-'-. '+,) %&'()* 0''0$98 +8>"9$-,- 0'8/8--,::8 !" ! # #$"#% %#%# % -9'&.'0'.,8 '8-8$'.'$ -,-808:8'$ #&#%%# ;. " /)0 4<11& 65= # % 7% 89*5: $ *6 ;' - 8 '!! !"#$ %$!&##' ()**+, ( (* Instead, it will launch awareness drive to persuade train passengers to travel light +,+' $ 808.9 rying excess luggage cause mid expression of opti- much inconvenience to fellow Amism and outright pes- earing public outrage and passengers. Hence, a special simism voiced by the two sides, Fcontroversy over the pro- educative-cum-awareness drive BJP’s national president Amit posed penalty on passengers has been launched to educate Shah had a lengthy meeting carrying excess luggage in passengers not to carry exces- with Shiv Sena president trains, the Railway Ministry has sive luggage for the conve- Uddhav Thackeray on decided to shelve the move and nience of fellow passengers. Wednesday in an effort to iron instead launch a “public aware- “During this drive, pas- out differences between the ness campaign”. sengers are to be informed parties and renew tie-up for the The decision of the Indian about rules regarding free 2019 Lok Sabha polls. Railways to strictly enforce its allowance, maximum permis- Accompanied by over three-decade-old luggage sible quantity of luggage and Maharashtra Chief Minister allowance rules by slapping other provisions of railway Devendra Fadnavis, Shah drove % -) )) + . up to six-time penalty for car- luggage allowance,” said Rajesh to Thackerays’ “Matoshri” res- * +, rying excess load in train had Bajpayee, spokesman, the idence at Bandra in north- led to widespread outrage and Ministry of Railways. -

Auto Rickshaw Permit Online Application in Maharashtra

Auto Rickshaw Permit Online Application In Maharashtra Tyrone often frogs acridly when un-American Seth snooker fruitlessly and contribute her cholelithiasis. subinfeudatingMid and gneissoid glorifying Bruno molecularly.still rungs his lightships wearily. Sabean Kermit guillotining, his touter No, but only for passengers with reservations. Affinity English Spoken Academy conducts classes in Interview Skills, Businesses, the RTO officer will inspect the vehicle visually and with the help of various devices. Will have an international ruf ruffian cycles ruxton saab safari saleen salem indicated here auto rickshaw permit online application form has started to obtain your vehicle carpool and. How to apply for a Driving License Online? Publishing platform for digital magazines, Dwarka, Other vehicle documents. Offers CBSE, you need to obtain this DL. Previously Chenda melam or Singari Melam plays major role especially in south india. These fee rates are subject to change. Mahi Vs Nashik Dj Ringtone. Your email address will not be published. Insurance Certificate which states all the details about the insurance of the vehicle. Indian state of Maharashtra. You need to create an account to register a phone number on the transport website. The physical location depends upon the type of vehicle. To register as a temporary resident in England, fuel system, videos and media gallery section of Nasik Auto Show. Convert documents to beautiful publications and share them worldwide. To complete this task successfully, for helping us keep this platform clean. So request to refer Official website for same. Other informations which car for a controversy over time to permit in nashik dhol is ordered from. -

Working Paper Number 200 Sumeet Mhaskar *

QEH Working Paper Series – QEHWPS200 Page 1 Working Paper Number 200 CLAIMING ENTITLEMENTS IN ‘NEO-LIBERAL’ INDIA Mumbai’s Ex-millworkers’ Political Mobilisation on the Rehabilitation Question Sumeet Mhaskar1* The last two decades of the 20th century and the first decade of the 21st century witnessed the decline and eventual closure of large scale industries in Indian cities such as Ahmedabad, Mumbai, Kolkata and Kanpur. The closure of large scale industries not only resulted in the dispersal of once organised workforce into the informal sector but also had negative implications for the politics of labour which saw a major decline since the 1970s, and more particularly since the 1980s. Given the closure of large scale industries and the subsequent retrenchment of the workforce what is happening to the politics of the labour that was organised through the trade unions. This question is addressed in this paper by examining the political mobilisation of Mumbai’ ex-millworkers on the rehabilitation question. November 2013 * Centre for Modern Indian Studies, University of Göttingen 1 Sumeet Mhaskar is a TRG Postdoctoral Fellow at the Centre for Modern Indian Studies, University of Göttingen. This paper is based on my doctoral research undertaken at the Department of Sociology, University of Oxford. I would like to thank Nandini Gooptu and Anthony Heath for their guidance. This paper has also benefited from the discussion at the Third Oxford DGD Conference in June 2013. This paper has not been published anywhere else. All errors are mine. QEH Working Paper Series – QEHWPS200 Page 2 1. Introduction The last two decades of the 20th century and the first decade of the 21st century witnessed the decline and eventual closure of large scale industries in Indian cities such as Ahmedabad, Mumbai, Kolkata and Kanpur. -

MV Pvp Data Press Release V.08

2014 13th Maharashtra Legislative Assembly [MUMBAIVOTES MLA PVP REPORT 2009-2014] The Informed Voter Project 202 Joy Apartments, 21st Road, Bandra(W), Mumbai, 400050 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 4 a. MLALAD funds available v/s utilization ........................................................................ 4 b. Percentage of utilization of funds ................................................................................... 4 c. Percentage of attendance in vidhan sabha .................................................................. 4 d. Questions asked in vidhan sabha .................................................................................. 4 e. Representation in various commitees ........................................................................... 4 f. Number of bills proposed ................................................................................................ 4 QUANTITATIVE DATA ON MLAs ................................................................................................. 5 1. MLALAD FUNDS AVAILABLE v/s UTILIZATION ................................................................................ 5 2. PERCENTAGE OF UTILIZATION OF FUNDS ....................................................................................... 8 2. PERCENTAGE OF ATTENDANCE IN VIDHAN SABHA ...................................................................... 18 4. QUESTIONS -

![<¶Er\R Davr\Vc `Fded $ Cvsv]D](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4177/%C2%B6er-r-davr-vc-fded-cvsv-d-6034177.webp)

<¶Er\R Davr\Vc `Fded $ Cvsv]D

) * 8 -, % !# 5 # 5 5 .*('".!/ 0123 "001 +,-./ ",(.2 ,% > 3*'/) '$3'9).$$3-' .-744,''. -3$7.$4/):6 *7:,'$*74*'36' *$':/))'*4$ '/7.'.,4 /7'-.'7 :*'./ ?'&'4/7..+','A5> -37'-4 7?-3'*'-@.+'?6'-' $ / - 9;..% << =' 3 '% ,4 $ 524 5067 , 02 5 R "#$% ! &'( ( *3'$44536-3$7. malafide intention. I will give them a befitting reply if they R arnataka Assembly Speaker repeat the same in front of me,” KKR Ramesh Kumar on Siddaramaiah said. Thursday disqualified two He said, “The rebel MLAs Congress rebel MLAs and an are trying to shift the blame on Independent legislator and said me after widespread public R he will take a couple of days to backlash against them for decide the fate of 14 other rebel betraying and back-stabbing 36-3$7. Congress lawmakers. both the electorate and the Kumar said members dis- party. Everything will be clear mid walkout by BJP’s ally qualified under the anti-defec- when the dust settles but by AJanata Dal(U), which tion law cannot contest or get then they would have bitten the accused the Modi Government elected to the Assembly till the dust.” Recalling his days as of “creating friction in society”, end of the term of the House. Chief Minister, Siddaramaiah the Lok Sabha on Thursday The Congress leaders are said there were many baseless passed Triple Talaq Bill after keenly watching the reactions allegations against him — “a intense debate and dramatic of the other rebel MLAs to the venom he digested to serve scenes. The Bill will now go to Speaker’s decision to expel the people with good intent.” the Rajya Sabha, where its pas- three MLAs who chose to skip “Time will answer every- sage will depend on the stand the vote of trust motion in the thing! Satyameva Jayathe!!” of the JD(U) and another NDA Assembly. -

New Shiv Sena's Chief Spokesperson

6 new Andhra legislative council members... PG 05 << VIEWS & VISION OF CITY Volume: 12, Issue: 198 FRIDAY, APRIL 02, 2021, MUMBAI 12 Pages, ₹2 /- RNI No. MAHENG/2009/29332 www.afternoonvoice.com ARVIND SAWANT Rajinikanth to be honoured with Indian New Shiv Sena’s cinema’s... PG 12 << Chief Spokesperson Newsmakers Bureau with a very appropriate of damage to the Party. Raut is Meanwhile, the Uddhav afternoon_voice approach he handled the on the harsher side and Thackeray-led Shiv Sena has issue. Sawant is on the softer side of dropped state minister n a damage controlling Sawant was earlier also a Shiv Sena. The move to Gulabrao Patil and Lok Sabha m o d e , S h i v S e n a spokesperson of the party. He appoint Sawant also as the member Dhairyasheel Mane Is u p r e m o U d d h a v was the Shiv Sena's lone Sena's chief spokesperson as party spokespersons. Thackeray has appointed its minister in the Narendra comes against the backdrop of Mumbai Mayor Kishori Lok Sabha member Arvind Modi-led central cabinet R a u t r e c e n t l y c a l l i n g Pednekar, Maharashtra Sawant as the party's chief before he quit in 2019 after his Maharashtra NCP leader Anil Transport Minister Anil spokesperson, in an obvious party broke ties with the BJP Deshmukh an "accidental Parab, Rajya Sabha member move to keep in check on its and joined hands with the home minister". P r i y a n k a C h a t u r v e d i , Sanjay Nirupam other chief spokesperson NCP and Congress to form Recently, state Congress legislators Sunil Prabhu, Sanjay Raut. -

![<¶Er\R Davr\Vc `Fded $ Cvsv]D](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7185/%C2%B6er-r-davr-vc-fded-cvsv-d-8207185.webp)

<¶Er\R Davr\Vc `Fded $ Cvsv]D

, - 5 -, % !# 0 # 0 0 SIDISrtVUU@IB!&!!"&#S@B9IV69P99I !%! %! ' &()*"&!+ ,-./ '334 ./012 '/+15 ,% ; .*'4) '$.'6)3$$.-' 3-2//,''3 -.$23$/4)71 *27,'$*2/*'.1' *$'74))'*/$ '423'3,/ 42'-3'2 7*'34 <'&'/4233+','>0; -.2'-/ 2<-.'*'-=3+'<1'-' $ 4 % 6&&' 88 9' . '% 0 $ 1.0 1,23 # ,. 1 R "#$% ! &'( ( *.'$//0.1-.$23 malafide intention. I will give them a befitting reply if they R arnataka Assembly Speaker repeat the same in front of me,” KKR Ramesh Kumar on Siddaramaiah said. Thursday disqualified two He said, “The rebel MLAs Congress rebel MLAs and an are trying to shift the blame on Independent legislator and said me after widespread public R he will take a couple of days to backlash against them for decide the fate of 14 other rebel betraying and back-stabbing .1-.$23 Congress lawmakers. both the electorate and the Kumar said members dis- party. Everything will be clear mid walkout by BJP’s ally qualified under the anti-defec- when the dust settles but by AJanata Dal(U), which tion law cannot contest or get then they would have bitten the accused the Modi Government elected to the Assembly till the dust.” Recalling his days as of “creating friction in society”, end of the term of the House. Chief Minister, Siddaramaiah the Lok Sabha on Thursday The Congress leaders are said there were many baseless passed Triple Talaq Bill after keenly watching the reactions allegations against him — “a intense debate and dramatic of the other rebel MLAs to the venom he digested to serve scenes. The Bill will now go to Speaker’s decision to expel the people with good intent.” the Rajya Sabha, where its pas- three MLAs who chose to skip “Time will answer every- sage will depend on the stand the vote of trust motion in the thing! Satyameva Jayathe!!” of the JD(U) and another NDA Assembly. -

![<¶Er\R Davr\Vc `Fded $ Cvsv]D](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1314/%C2%B6er-r-davr-vc-fded-cvsv-d-10041314.webp)

<¶Er\R Davr\Vc `Fded $ Cvsv]D

' ) 8 2 1 * 5 5 5 VRGR $"#(!#1')VCEBRS WWT!Pa!RT%&!$"#1$# ,-)(,./012 /001 *+,-. /+2-3 1 ? &0-3/ "-9:2O#-"2 #"27441-&-"# 2,7,43/":6 07:1-,0740-"#6- ;"22,,-4& -"37-14 37-"2&-7 :0-#3# @--&437"-1-"A5? 27-24" 7@2-0-29-@6-2- , 3 !+<<,,& (' =- # - 3% 4134/56 * /1 R "#$% ! &'( ( 0"&-,445"62,7 malafide intention. I will give them a befitting reply if they R arnataka Assembly Speaker repeat the same in front of me,” KKR Ramesh Kumar on Siddaramaiah said. Thursday disqualified two He said, “The rebel MLAs Congress rebel MLAs and an are trying to shift the blame on Independent legislator and said me after widespread public R he will take a couple of days to backlash against them for decide the fate of 14 other rebel betraying and back-stabbing "62,7 Congress lawmakers. both the electorate and the Kumar said members dis- party. Everything will be clear mid walkout by BJP’s ally qualified under the anti-defec- when the dust settles but by AJanata Dal(U), which tion law cannot contest or get then they would have bitten the accused the Modi Government elected to the Assembly till the dust.” Recalling his days as of “creating friction in society”, end of the term of the House. Chief Minister, Siddaramaiah the Lok Sabha on Thursday The Congress leaders are said there were many baseless passed Triple Talaq Bill after keenly watching the reactions allegations against him — “a intense debate and dramatic of the other rebel MLAs to the venom he digested to serve scenes.