Causes of the Quaternary Megafauna Extinction Event

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of Large Terrestrial Carnivores on Pleistocene Ecosystems Blaire Van Valkenburgh, Matthew W

The impact of large terrestrial carnivores on SPECIAL FEATURE Pleistocene ecosystems Blaire Van Valkenburgha,1, Matthew W. Haywardb,c,d, William J. Ripplee, Carlo Melorof, and V. Louise Rothg aDepartment of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095; bCollege of Natural Sciences, Bangor University, Bangor, Gwynedd LL57 2UW, United Kingdom; cCentre for African Conservation Ecology, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth, South Africa; dCentre for Wildlife Management, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa; eTrophic Cascades Program, Department of Forest Ecosystems and Society, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331; fResearch Centre in Evolutionary Anthropology and Palaeoecology, School of Natural Sciences and Psychology, Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool L3 3AF, United Kingdom; and gDepartment of Biology, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708-0338 Edited by Yadvinder Malhi, Oxford University, Oxford, United Kingdom, and accepted by the Editorial Board August 6, 2015 (received for review February 28, 2015) Large mammalian terrestrial herbivores, such as elephants, have analogs, making their prey preferences a matter of inference, dramatic effects on the ecosystems they inhabit and at high rather than observation. population densities their environmental impacts can be devas- In this article, we estimate the predatory impact of large (>21 tating. Pleistocene terrestrial ecosystems included a much greater kg, ref. 11) Pleistocene carnivores using a variety of data from diversity of megaherbivores (e.g., mammoths, mastodons, giant the fossil record, including species richness within guilds, pop- ground sloths) and thus a greater potential for widespread habitat ulation density inferences based on tooth wear, and dietary in- degradation if population sizes were not limited. -

Megafauna Extinction, Tree Species Range Reduction, and Carbon Storage in Amazonian Forests

Ecography 39: 194–203, 2016 doi: 10.1111/ecog.01587 © 2015 The Authors. Ecography © 2015 Nordic Society Oikos Subject Editor: Yadvinder Mahli. Editor-in-Chief: Nathan J. Sanders. Accepted 27 September 2015 Megafauna extinction, tree species range reduction, and carbon storage in Amazonian forests Christopher E. Doughty, Adam Wolf, Naia Morueta-Holme, Peter M. Jørgensen, Brody Sandel, Cyrille Violle, Brad Boyle, Nathan J. B. Kraft, Robert K. Peet, Brian J. Enquist, Jens-Christian Svenning, Stephen Blake and Mauro Galetti C. E. Doughty ([email protected]), Environmental Change Inst., School of Geography and the Environment, Univ. of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3QY, UK. – A. Wolf, Dept of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Princeton Univ., Princeton, NJ 08544, USA. – N. Morueta-Holme, Dept of Integrative Biology, Univ. of California – Berkeley, CA 94720, USA. – B. Sandel, J.-C. Svenning and NM-H, Section for Ecoinformatics and Biodiversity, Dept of Bioscience, Aarhus Univ., Ny Munkegade 114, DK-8000 Aarhus C, Denmark. – P. M. Jørgensen, Missouri Botanical Garden, PO Box 299, St Louis, MO 63166-0299, USA. – C. Violle, CEFE UMR 5175, CNRS – Univ. de Montpellier – Univ. Paul-Valéry Montpellier – EPHE – 1919 route de Mende, FR-34293 Montpellier Cedex 5, France. – B. Boyle and B. J. Enquist, Dept of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Univ. of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA. – N. J. B. Kraft, Dept of Biology, Univ. of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742, USA. BJE also at: The Santa Fe inst., 1399 Hyde Park Road, Santa Fe, NM 87501, USA. – R. K. Peet, Dept of Biology, Univ. of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3280, USA. -

The Asymmetry in the Great American Biotic Interchange in Mammals Is Consistent with Differential Susceptibility to Mammalian Predation

Coversheet This is the accepted manuscript (post-print version) of the article. Contentwise, the accepted manuscript version is identical to the final published version, but there may be differences in typography and layout. How to cite this publication Please cite the final published version: Faurby, S. and Svenning, J.-C. (2016), The asymmetry in the Great American Biotic Interchange in mammals is consistent with differential susceptibility to mammalian predation. Global Ecol. Biogeogr., 25: 1443–1453. doi:10.1111/geb.12504 Publication metadata Title: The asymmetry in the Great American Biotic Interchange in mammals is consistent with differential susceptibility to mammalian predation Author(s): Faurby, S. and Svenning, J.-C. Journal: Global Ecology and Biogeography DOI/Link: https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12504 Document version: Accepted manuscript (post-print) This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: [Faurby, S. and Svenning, J.-C. (2016), The asymmetry in the Great American Biotic Interchange in mammals is consistent with differential susceptibility to mammalian predation. Global Ecol. Biogeogr., 25: 1443–1453. doi:10.1111/geb.12504], which has been published in final form at [https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12504]. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Self-Archiving. General Rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. -

Archaeology Resources

Archaeology Resources Page Intentionally Left Blank Archaeological Resources Background Archaeological Resources are defined as “any prehistoric or historic district, site, building, structure, or object [including shipwrecks]…Such term includes artifacts, records, and remains which are related to such a district, site, building, structure, or object” (National Historic Preservation Act, Sec. 301 (5) as amended, 16 USC 470w(5)). Archaeological resources are either historic or prehistoric and generally include properties that are 50 years old or older and are any of the following: • Associated with events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of our history • Associated with the lives of persons significant in the past • Embody the distinctive characteristics of a type, period, or method of construction • Represent the work of a master • Possess high artistic values • Present a significant and distinguishable entity whose components may lack individual distinction • Have yielded, or may be likely to yield, information important in history These resources represent the material culture of past generations of a region’s prehistoric and historic inhabitants, and are basic to our understanding of the knowledge, beliefs, art, customs, property systems, and other aspects of the nonmaterial culture. Further, they are subject to National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) review if they are historic properties, meaning those that are on, or eligible for placement on, the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). These sites are referred to as historic properties. Section 106 requires agencies to make a reasonable and good faith efforts to identify historic properties. Archaeological resources may be found in the Proposed Project Area both offshore and onshore. -

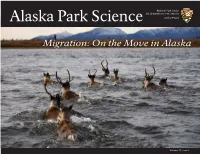

Migration: on the Move in Alaska

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Alaska Park Science Alaska Region Migration: On the Move in Alaska Volume 17, Issue 1 Alaska Park Science Volume 17, Issue 1 June 2018 Editorial Board: Leigh Welling Jim Lawler Jason J. Taylor Jennifer Pederson Weinberger Guest Editor: Laura Phillips Managing Editor: Nina Chambers Contributing Editor: Stacia Backensto Design: Nina Chambers Contact Alaska Park Science at: [email protected] Alaska Park Science is the semi-annual science journal of the National Park Service Alaska Region. Each issue highlights research and scholarship important to the stewardship of Alaska’s parks. Publication in Alaska Park Science does not signify that the contents reflect the views or policies of the National Park Service, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute National Park Service endorsement or recommendation. Alaska Park Science is found online at: www.nps.gov/subjects/alaskaparkscience/index.htm Table of Contents Migration: On the Move in Alaska ...............1 Future Challenges for Salmon and the Statewide Movements of Non-territorial Freshwater Ecosystems of Southeast Alaska Golden Eagles in Alaska During the A Survey of Human Migration in Alaska's .......................................................................41 Breeding Season: Information for National Parks through Time .......................5 Developing Effective Conservation Plans ..65 History, Purpose, and Status of Caribou Duck-billed Dinosaurs (Hadrosauridae), Movements in Northwest -

Species Extinctions

http://www.iucn.org/about/union/commissions/wcpa/?7695/Multiple-ocean-stresses- threaten-globally-significant-marine-extinction Multiple ocean stresses threaten “globally significant” marine extinction 20 June 2011 | News story An international panel of experts warns in a report released today that marine species are at risk of entering a phase of extinction unprecedented in human history. The preliminary report arises from a ‘State of the Oceans’ workshop co-hosted by IUCN in April, the first ever to consider the cumulative impact of all pressures on the oceans. Considering the latest research across all areas of marine science, the workshop examined the combined effects of pollution, acidification, ocean warming, over-fishing and hypoxia (deoxygenation). The scientific panel concluded that the combination of stresses on the ocean is creating the conditions associated with every previous major extinction of species in Earth’s history. And the speed and rate of degeneration in the ocean is far greater than anyone has predicted. The panel concluded that many of the negative impacts previously identified are greater than the worst predictions. As a result, although difficult to assess, the first steps to globally significant extinction may have begun with a rise in the extinction threat to marine species such as reef- forming corals. “The world’s leading experts on oceans are surprised by the rate and magnitude of changes we are seeing,” says Dan Laffoley, Marine Chair of IUCN’s World Commission on Protected Areas, Senior Advisor on Marine Science and Conservation for IUCN and co-author of the report. “The challenges for the future of the ocean are vast, but unlike previous generations, we know what now needs to happen. -

Variable Impact of Late-Quaternary Megafaunal Extinction in Causing

Variable impact of late-Quaternary megafaunal SPECIAL FEATURE extinction in causing ecological state shifts in North and South America Anthony D. Barnoskya,b,c,1, Emily L. Lindseya,b, Natalia A. Villavicencioa,b, Enrique Bostelmannd,2, Elizabeth A. Hadlye, James Wanketf, and Charles R. Marshalla,b aDepartment of Integrative Biology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720; bMuseum of Paleontology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720; cMuseum of Vertebrate Zoology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720; dRed Paleontológica U-Chile, Laboratoria de Ontogenia, Departamento de Biología, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Chile, Chile; eDepartment of Biology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305; and fDepartment of Geography, California State University, Sacramento, CA 95819 Edited by John W. Terborgh, Duke University, Durham, NC, and approved August 5, 2015 (received for review March 16, 2015) Loss of megafauna, an aspect of defaunation, can precipitate many megafauna loss, and if so, what does this loss imply for the future ecological changes over short time scales. We examine whether of ecosystems at risk for losing their megafauna today? megafauna loss can also explain features of lasting ecological state shifts that occurred as the Pleistocene gave way to the Holocene. We Approach compare ecological impacts of late-Quaternary megafauna extinction The late-Quaternary impact of losing 70–80% of the megafauna in five American regions: southwestern Patagonia, the Pampas, genera in the Americas (19) would be expected to trigger biotic northeastern United States, northwestern United States, and Berin- transitions that would be recognizable in the fossil record in at gia. We find that major ecological state shifts were consistent with least two respects. -

Disease Introduction by Aboriginal Humans in North America and the Pleistocene Extinction

Journal of Ecological Anthropology Volume 19 Issue 1 Volume 19, Issue 1 (2017) Article 2 April 2017 Disease Introduction by Aboriginal Humans in North America and the Pleistocene Extinction Zachary D. Nickell Hendrix College Matthew D. Moran Hendrix College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jea Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Immunology and Infectious Disease Commons Recommended Citation Nickell, Zachary D. and Moran, Matthew D.. "Disease Introduction by Aboriginal Humans in North America and the Pleistocene Extinction." Journal of Ecological Anthropology 19, no. 1 (2017): 29-41. Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jea/vol19/iss1/2 This Crib Notes is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Ecological Anthropology by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Disease Introduction by Aboriginal Humans in North America and the Pleistocene Extinction Cover Page Footnote ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thanks to C. N. Davis and R. Wells who provided valuable comments to earlier versions of this manuscript. Three anonymous reviewers greatly improved the manuscript. The project was supported in part by a grant to Z. Nickell from the Hendrix College Odyssey Program This crib notes is available in Journal of Ecological Anthropology: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jea/vol19/iss1/2 Moran & Nickell / Introduced Disease and Pleistocene Extinction CRIB NOTES Disease Introduction by Aboriginal Humans in North America and the Pleistocene Extinction Zachary D. Nickell Matthew D. Moran ABSTRACT While overhunting and climate change have been the major hypotheses to explain the late-Pleistocene New World megafaunal extinctions, the role of introduced disease has only received brief attention. -

La Brea and Beyond: the Paleontology of Asphalt-Preserved Biotas

La Brea and Beyond: The Paleontology of Asphalt-Preserved Biotas Edited by John M. Harris Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Science Series 42 September 15, 2015 Cover Illustration: Pit 91 in 1915 An asphaltic bone mass in Pit 91 was discovered and exposed by the Los Angeles County Museum of History, Science and Art in the summer of 1915. The Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History resumed excavation at this site in 1969. Retrieval of the “microfossils” from the asphaltic matrix has yielded a wealth of insect, mollusk, and plant remains, more than doubling the number of species recovered by earlier excavations. Today, the current excavation site is 900 square feet in extent, yielding fossils that range in age from about 15,000 to about 42,000 radiocarbon years. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Archives, RLB 347. LA BREA AND BEYOND: THE PALEONTOLOGY OF ASPHALT-PRESERVED BIOTAS Edited By John M. Harris NO. 42 SCIENCE SERIES NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM OF LOS ANGELES COUNTY SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE Luis M. Chiappe, Vice President for Research and Collections John M. Harris, Committee Chairman Joel W. Martin Gregory Pauly Christine Thacker Xiaoming Wang K. Victoria Brown, Managing Editor Go Online to www.nhm.org/scholarlypublications for open access to volumes of Science Series and Contributions in Science. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Los Angeles, California 90007 ISSN 1-891276-27-1 Published on September 15, 2015 Printed at Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas PREFACE Rancho La Brea was a Mexican land grant Basin during the Late Pleistocene—sagebrush located to the west of El Pueblo de Nuestra scrub dotted with groves of oak and juniper with Sen˜ora la Reina de los A´ ngeles del Rı´ode riparian woodland along the major stream courses Porciu´ncula, now better known as downtown and with chaparral vegetation on the surrounding Los Angeles. -

Megafauna Extinction

Episode 15 Teacher Resource 2nd June 2020 Megafauna Extinction 1. Before watching the BTN story, record what you know about Students will learn more about Australian megafauna and megafauna. investigate why they became 2. What is megafauna? extinct. 3. About how many years ago did megafauna exist in Australia? a. 4,000 b. 40,000 c. 400,000 Science – Year 6 The growth and survival of living 4. Complete the following sentence. A Diprotodon was a giant things are affected by physical _________________. conditions of their environment. 5. What did palaeontologist Dr Scott Hocknull and his team discover? Science – Year 7 6. Where did they make the discovery? Scientific knowledge has changed peoples’ understanding of the 7. What did they use to create images of what the megafauna might world and is refined as new have looked like? evidence becomes available. 8. Give some examples of the megafauna species they discovered. Interactions between organisms, 9. What might have caused megafauna to become extinct? including the effects of human 10. What did you learn watching the BTN story? activities can be represented by food chains and food webs. What do you know about megafauna? As a class discuss the BTN Megafauna Extinction story and ask students to record what they learnt watching the story. Record any questions they have. Here are some questions they can use to help guide their discussion. • What does the term megafauna mean? • When did megafauna exist? • How do we know they existed? • Why did megafauna grow so big? • What might have caused Australia’s megafauna to die out? Glossary Students will brainstorm a list of key words and terms that relate to the BTN Megafauna Extinction story. -

Simple Stochastic Populations in Habi- Tats with Bounded, and Varying Carry- Ing Capacities

Simple Stochastic Populations in Habi- tats with Bounded, and Varying Carry- ing Capacities Master’s thesis in Complex Adaptive Systems EDWARD KORVEH Department of Mathematical Sciences CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Gothenburg, Sweden 2016 Master’s thesis 2016:NN Simple Stochastic Populations in Habitats with Bounded, and Varying Carrying Capacities EDWARD KORVEH Department of Mathematical Sciences Division of Mathematical Statistics Chalmers University of Technology Gothenburg, Sweden 2016 Simple Stochastic Populations in Habitats with Bounded, and Varying Carrying Capacities EDWARD KORVEH © EDWARD KORVEH, 2016. Supervisor: Peter Jagers, Department of Mathematical Sciences Examiner: Peter Jagers, Department of Mathematical Sciences Master’s Thesis 2016:NN Department of Mathematical Sciences Division of Mathematical Statistics Chalmers University of Technology SE-412 96 Gothenburg Gothenburg, Sweden 2016 iv Simple Stochastic Populations in Habitats with Bounded, and Varying Carrying Capacities EDWARD KORVEH Department of Mathematical Sciences Chalmers University of Technology Abstract A population consisting of one single type of individuals where reproduction is sea- sonal, and by means of asexual binary-splitting with a probability, which depends on the carrying capacity of the habitat, K and the present population is considered. Current models for such binary-splitting populations do not explicitly capture the concepts of early and late extinctions. A new parameter v, called the ‘scaling pa- rameter’ is introduced to scale down the splitting probabilities in the first season, and also in subsequent generations in order to properly observe and record early and late extinctions. The modified model is used to estimate the probabilities of early and late extinctions, and the expected time to extinction in two main cases. -

The Sixth Great Extinction Donations Events "Soon a Millennium Will End

The Rewilding Institute, Dave Foreman, continental conservation Home | Contact | The EcoWild Program | Around the Campfire About Us Fellows The Pleistocene-Holocene Event: Mission Vision The Sixth Great Extinction Donations Events "Soon a millennium will end. With it will pass four billion years of News evolutionary exuberance. Yes, some species will survive, particularly the smaller, tenacious ones living in places far too dry and cold for us to farm or graze. Yet we Resources must face the fact that the Cenozoic, the Age of Mammals which has been in retreat since the catastrophic extinctions of the late Pleistocene is over, and that the Anthropozoic or Catastrophozoic has begun." --Michael Soulè (1996) [Extinction is the gravest conservation problem of our era. Indeed, it is the gravest problem humans face. The following discussion is adapted from Chapters 1, 2, and 4 of Dave Foreman’s Rewilding North America.] Click Here For Full PDF Report... or read report below... Many of our reports are in Adobe Acrobat PDF Format. If you don't already have one, the free Acrobat Reader can be downloaded by clicking this link. The Crisis The most important—and gloomy—scientific discovery of the twentieth century was the extinction crisis. During the 1970s, field biologists grew more and more worried by population drops in thousands of species and by the loss of ecosystems of all kinds around the world. Tropical rainforests were falling to saw and torch. Wetlands were being drained for agriculture. Coral reefs were dying from god knows what. Ocean fish stocks were crashing. Elephants, rhinos, gorillas, tigers, polar bears, and other “charismatic megafauna” were being slaughtered.