Racial Discrimination in Major League Baseball: Can It Exist When Performance Is Crystal Clear?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"What Raw Statistics Have the Greatest Effect on Wrc+ in Major League Baseball in 2017?" Gavin D

1 "What raw statistics have the greatest effect on wRC+ in Major League Baseball in 2017?" Gavin D. Sanford University of Minnesota Duluth Honors Capstone Project 2 Abstract Major League Baseball has different statistics for hitters, fielders, and pitchers. The game has followed the same rules for over a century and this has allowed for statistical comparison. As technology grows, so does the game of baseball as there is more areas of the game that people can monitor and track including pitch speed, spin rates, launch angle, exit velocity and directional break. The website QOPBaseball.com is a newer website that attempts to correctly track every pitches horizontal and vertical break and grade it based on these factors (Wilson, 2016). Fangraphs has statistics on the direction players hit the ball and what percentage of the time. The game of baseball is all about quantifying players and being able give a value to their contributions. Sabermetrics have given us the ability to do this in far more depth. Weighted Runs Created Plus (wRC+) is an offensive stat which is attempted to quantify a player’s total offensive value (wRC and wRC+, Fangraphs). It is Era and park adjusted, meaning that the park and year can be compared without altering the statistic further. In this paper, we look at what 2018 statistics have the greatest effect on an individual player’s wRC+. Keywords: Sabermetrics, Econometrics, Spin Rates, Baseball, Introduction Major League Baseball has been around for over a century has given awards out for almost 100 years. The way that these awards are given out is based on statistics accumulated over the season. -

October, 1998

By the Numbers Volume 8, Number 1 The Newsletter of the SABR Statistical Analysis Committee October, 1998 RSVP Phil Birnbaum, Editor Well, here we go again: if you want to continue to receive By the If you already replied to my September e-mail, you don’t need to Numbers, you’ll have to drop me a line to let me know. We’ve reply again. If you didn’t receive my September e-mail, it means asked this before, and I apologize if you’re getting tired of it, but that the committee has no e-mail address for you. If you do have there’s a good reason for it: our committee budget. an e-mail address but we don’t know about it, please let Neal Traven (our committee chair – see his remarks later this issue) Our budget is $500 per year. know, so that we can communicate with you more easily. Giving us your e-mail address does not register you to receive BTN by e- Our current committee member list numbers about 200. Of the mail. Unless you explicitly request that, I’ll continue to send 200 of us, 50 have agreed to accept delivery of this newsletter by BTN by regular mail. e-mail. That leaves 150 readers who need physical copies of BTN. At four issues a year, that’s 600 mailings, and there’s no As our 1998 budget has not been touched until now, we have way to do 600 photocopyings and mailings for $500. sufficient funds left over for one more full issue this year. -

Salary Correlations with Batting Performance

Salary correlations with batting performance By: Jaime Craig, Avery Heilbron, Kasey Kirschner, Luke Rector, Will Kunin Introduction Many teams pay very high prices to acquire the players needed to make that team the best it can be. While it often seems that high budget teams like the New York Yankees are often very successful, is the high price tag worth the improvement in performance? We compared many statistics including batting average, on base percentage, slugging, on base plus slugging, home runs, strike outs, stolen bases, runs created, and BABIP (batting average for balls in play) to salaries. We predicted that higher salaries will correlate to better batting performances. We also divided players into three groups by salary range, with the low salary range going up to $1 million per year, the mid-range salaries from $1 million to $10 million per year, and the high salaries greater than $10 million per year. We expected a stronger correlation between batting performance and salaries for players in the higher salary range than the correlation in the lower salary ranges. Low Salary Below $1 million In figure 1 is a correlation plot between salary and batting statistics. This correlation plot is for players that are making below $1 million. We see in all of the plots that there is not a significant correlation between salary and batting statistics. It is , however, evident that players earning the lowest salaries show the lowest correlations. The overall trend for low salary players--which would be expected--is a negative correlation between salary and batting performance. This negative correlation is likely a result of players getting paid according to their specific performance, or the data are reflecting underpaid rookies who have not bloomed in the major leagues yet. -

Determining the Value of a Baseball Player

the Valu a Samuel Kaufman and Matthew Tennenhouse Samuel Kaufman Matthew Tennenhouse lllinois Mathematics and Science Academy: lllinois Mathematics and Science Academy: Junior (11) Junior (11) 61112012 Samuel Kaufman and Matthew Tennenhouse June 1,2012 Baseball is a game of numbers, and there are many factors that impact how much an individual player contributes to his team's success. Using various statistical databases such as Lahman's Baseball Database (Lahman, 2011) and FanGraphs' publicly available resources, we compiled data and manipulated it to form an overall formula to determine the value of a player for his individual team. To analyze the data, we researched formulas to determine an individual player's hitting, fielding, and pitching production during games. We examined statistics such as hits, walks, and innings played to establish how many runs each player added to their teams' total runs scored, and then used that value to figure how they performed relative to other players. Using these values, we utilized the Pythagorean Expected Wins formula to calculate a coefficient reflecting the number of runs each team in the Major Leagues scored per win. Using our statistic, baseball teams would be able to compare the impact of their players on the team when evaluating talent and determining salary. Our investigation's original focusing question was "How much is an individual player worth to his team?" Over the course of the year, we modified our focusing question to: "What impact does each individual player have on his team's performance over the course of a season?" Though both ask very similar questions, there are significant differences between them. -

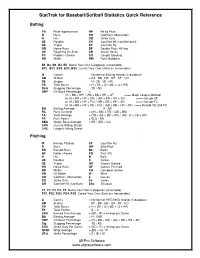

Stattrak for Baseball/Softball Statistics Quick Reference

StatTrak for Baseball/Softball Statistics Quick Reference Batting PA Plate Appearances HP Hit by Pitch R Runs CO Catcher's Obstruction H Hits SO Strike Outs 2B Doubles SH Sacrifice Hit (sacrifice bunt) 3B Triples SF Sacrifice Fly HR Home Runs DP Double Plays Hit Into OE Reaching On-Error SB Stolen Bases FC Fielder’s Choice CS Caught Stealing BB Walks RBI Runs Batted In B1, B2, B3, B4, B5 Name Your Own Categories (renamable) BS1, BS2, BS3, BS4, BS5 Create Your Own Statistics (renamable) G Games = Number of Batting records in database AB At Bats = PA - BB - HP - SH - SF - CO 1B Singles = H - 2B - 3B - HR TB Total Bases = H + 2B + (2 x 3B) + (3 x HR) SLG Slugging Percentage = TB / AB OBP On-Base Percentage = (H + BB + HP) / (AB + BB + HP + SF) <=== Major League Method or (H + BB + HP + OE) / (AB + BB + HP + SF) <=== Include OE or (H + BB + HP + FC) / (AB + BB + HP + SF) <=== Include FC or (H + BB + HP + OE + FC) / (AB + BB + HP + SF) <=== Include OE and FC BA Batting Average = H / AB RC Runs Created = ((H + BB) x TB) / (AB + BB) TA Total Average = (TB + SB + BB + HP) / (AB - H + CS + DP) PP Pure Power = SLG - BA SBA Stolen Base Average = SB / (SB + CS) CHS Current Hitting Streak LHS Longest Hitting Streak Pitching IP Innings Pitched SF Sacrifice Fly R Runs WP Wild Pitch ER Earned-Runs Bk Balks BF Batters Faced PO Pick Offs H Hits B Balls 2B Doubles S Strikes 3B Triples GS Games Started HR Home Runs GF Games Finished BB Walks CG Complete Games HB Hit Batter W Wins CO Catcher's Obstruction L Losses SO Strike Outs Sv Saves SH Sacrifice Hit -

Package 'Mlbstats'

Package ‘mlbstats’ March 16, 2018 Type Package Title Major League Baseball Player Statistics Calculator Version 0.1.0 Author Philip D. Waggoner <[email protected]> Maintainer Philip D. Waggoner <[email protected]> Description Computational functions for player metrics in major league baseball including bat- ting, pitching, fielding, base-running, and overall player statistics. This package is actively main- tained with new metrics being added as they are developed. License MIT + file LICENSE Encoding UTF-8 LazyData true RoxygenNote 6.0.1 NeedsCompilation no Repository CRAN Date/Publication 2018-03-16 09:15:57 UTC R topics documented: ab_hr . .2 aera .............................................3 ba ..............................................4 baa..............................................4 babip . .5 bb9 .............................................6 bb_k.............................................6 BsR .............................................7 dice .............................................7 EqA.............................................8 era..............................................9 erc..............................................9 fip.............................................. 10 fp .............................................. 11 1 2 ab_hr go_ao . 11 gpa.............................................. 12 h9.............................................. 13 iso.............................................. 13 k9.............................................. 14 k_bb............................................ -

The Impact of Hitters on Winning Percentage and Salary Using Sabermetrics

Mandrik 1 The Impact of Hitters on Winning Percentage and Salary Using Sabermetrics Zach Mandrik Professor Deprano 4/11/2017 Economics 490 Directed Research Abstract This paper addresses the question if advanced sabermetrics and traditional statistics are efficient predictors in estimating a hitter’s salary entering free agency. In addition the research also looks to answer if these same statistics can significantly predict a team’s winning percentage. Using data from 1985-2011, the models found that both traditional and advanced baseball metrics are significant in relation to salary and winning percentage. However, all of the regression models have low explanatory power in their ability to forecast results. I suggest that MLB clubs use these models as a checkpoint for free agent player salaries and/or ability to contribute to a team (winning percentage), rather than as an absolute determination of these variables. Mandrik 2 Overview Introduction Literature Review Statistics Review wOBA wRC+ BsR Regression Models The Data What are the outputs telling us? Forecasts and Analysis Conclusion Suggestions for the Sabermetrics Community References Appendix; Graphs and Tables Mandrik 3 Introduction One of the major goals for a baseball franchise, or any professional sports franchise in general, is to ultimately win a championship to bring in fans. Winning as a result typically brings an inflow of revenue, which is an owner’s desire. A portion of building a winning baseball team is centered on statistics and analytics. Thanks to the works of Bill James and many other baseball analysts, the development of sabermetrics has revolutionized the way business is done in baseball. -

Identifying Runs Created from 4-Seamer Alone MLB Average

Identifying runs created from 4-seamer alone This is the eighth of a series of preseason articles about the impact of air density on baseball performance, written for DailyBaseballData.com by Clifton Neeley of www.baseballVMI.com . When teams travel to Coors Field, they hit the four-seam fastball on the first day at a clip of 12.13% of strikes thrown when their VMI is identified as a high plus rating; by the third game it is down to the 9% range. This rating is due to the larger movement on the four-seam fastball the team has recently experienced prior to arriving at Coors Field. MLB Average Road Runs Created Against Four-Seam Fastball 2015 Road Games Percentage of Average Runs Road Games Percentage of Average Runs W/Less bite on hits to strikes MLB runs Created W/More bite hits to strikes MLB runs Created pitch for hitter to when less bite generated per 100 on pitch for w/more bite generated per 100 adjust to: on pitch per hit strikes hitter to adjust on pitch per hit strikes (series) to: (series) Normal baseball Normal between +0.00 to baseball +10.00 9.04% 0.045 4.52 between 8.61% 0.043 4.31 -0.00 to -10.00 Per game= 1.49 Per game= 1.42 Easier Hitting Tougher between +10.00 to Hitting +15.00 11.75% 0.059 5.88 between -0.00 7.16% 0.036 3.58 to -15.00 Per game= 1. 94 Per game= 1.18 Visitors to Coors Teams Leaving Field between Coors Field +15.00 to +25.00 12.13% 0.061 6.06 -15.00 to - 8.19% 0.041 4.10 25.00 Per game= 2.00 Per game= 1.35 Visual Memory by Clifton Neeley, creator of the Visual Memory Index© and author of the web-site www.baseballvmi.com . -

Baseball with Popcorn, Statistics and SAS - What a Mix David Franklin, Theprogrammerscabin.Com, Litchfield, NH

NESUG 2011 Statistics & Analysis Baseball with Popcorn, Statistics and SAS - What A Mix David Franklin, TheProgrammersCabin.com, Litchfield, NH ABSTRACT The year is almost over. At the end of September another year of baseball will be over. Then the talk will be over who was the best player for the season – a look at the statistics will those who make this decision. Statistics in sports has been around since sports were first played, and where there is statistics, SAS® is not far behind. This paper looks at Baseball statistics, how they were developed, then look at the how some of the more common statistics are calculated. Finally, a program will be presented that was developed and used in local minor league to solve the riddle of who was the best pitcher and batter. INTRODUCTION Baseball statistics can be traced back to its roots in cricket. It was a person by the name of Henry Chadwick in the 19th century who first brought the science of numbers to the sport with his experience in cricket statistics. From the start statistics such as the batting average and earned run average have been prominent. However in recent years there have been a new slew of statistics computed that draw attention to almost every facet of baseball, whether it be batting, pitching or fielding. This paper will have a look at how a few of the more common statistics that are calculated, and then show an example based on the real world in a local minor league where the question was answered, who was the best pitcher and best batter for the season. -

Major Qualifying Project: Advanced Baseball Statistics

Major Qualifying Project: Advanced Baseball Statistics Matthew Boros, Elijah Ellis, Leah Mitchell Advisors: Jon Abraham and Barry Posterro April 30, 2020 Contents 1 Background 5 1.1 The History of Baseball . .5 1.2 Key Historical Figures . .7 1.2.1 Jerome Holtzman . .7 1.2.2 Bill James . .7 1.2.3 Nate Silver . .8 1.2.4 Joe Peta . .8 1.3 Explanation of Baseball Statistics . .9 1.3.1 Save . .9 1.3.2 OBP,SLG,ISO . 10 1.3.3 Earned Run Estimators . 10 1.3.4 Probability Based Statistics . 11 1.3.5 wOBA . 12 1.3.6 WAR . 12 1.3.7 Projection Systems . 13 2 Aggregated Baseball Database 15 2.1 Data Sources . 16 2.1.1 Retrosheet . 16 2.1.2 MLB.com . 17 2.1.3 PECOTA . 17 2.1.4 CBS Sports . 17 2.2 Table Structure . 17 2.2.1 Game Logs . 17 2.2.2 Play-by-Play . 17 2.2.3 Starting Lineups . 18 2.2.4 Team Schedules . 18 2.2.5 General Team Information . 18 2.2.6 Player - Game Participation . 18 2.2.7 Roster by Game . 18 2.2.8 Seasonal Rosters . 18 2.2.9 General Team Statistics . 18 2.2.10 Player and Team Specific Statistics Tables . 19 2.2.11 PECOTA Batting and Pitching . 20 2.2.12 Game State Counts by Year . 20 2.2.13 Game State Counts . 20 1 CONTENTS 2 2.3 Conclusion . 20 3 Cluster Luck 21 3.1 Quantifying Cluster Luck . 22 3.2 Circumventing Cluster Luck with Total Bases . -

Package 'Baseballdbr'

Package ‘baseballDBR’ June 15, 2017 Type Package Title Sabermetrics and Advanced Baseball Statistics Version 0.1.2 Description A tool for gathering and analyzing data from the Baseball Data- bank <http://www.baseball-databank.org/>, which includes player performance statis- tics from major league baseball in the United States beginning in the year 1871. Depends R (>= 3.3.3) Imports rvest, xml2, magrittr, dplyr Suggests testthat, tidyr, rmarkdown, knitr, Lahman License MIT + file LICENSE URL https://github.com/keberwein/moneyball BugReports https://github.com/keberwein/moneyball/issues LazyData true RoxygenNote 6.0.1 VignetteBuilder knitr NeedsCompilation no Author Kris Eberwein [aut, cre] Maintainer Kris Eberwein <[email protected]> Repository CRAN Date/Publication 2017-06-15 15:19:17 UTC R topics documented: BA..............................................2 BABIP............................................3 baseballDBR . .4 BBpct . .4 BB_9 ............................................5 Ch..............................................5 1 2 BA CTpct . .6 FIP..............................................7 fip_values . .8 Fld_pct . .8 get_bbdb . .9 HRpct . 10 HR_9 ............................................ 11 H_9 ............................................. 11 IP .............................................. 12 ISO ............................................. 13 Kpct............................................. 13 K_9 ............................................. 14 LOB_pct . 15 OBP............................................. 15 -

Salary Correlations with Batting Performance

Salary correlations with batting performance By Jaime Craig, Avery Heilbron, Kasey Kirschner, Luke Rector, Will Kunin Introduction Many teams pay very high prices to acquire the players needed to make that team the best it can be. While it often seems that high budget teams like the New York Yankees are often very successful, is the high price tag worth the improvement in performance? We compared many statistics including batting average, on base percentage, slugging, on base plus slugging, home runs, strike outs, stolen bases, runs created, and BABIP (batting average for balls in play) to salaries. It is expected that higher salaries will correlate to better batting performances. We also divided players into three groups by salary range, with the low salary range going up to $1 million per year, the mid-range salaries from $1 million to $10 million per year, and the high salaries greater than $10 million per year. We expect a stronger correlation between batting performance and salaries for players in the higher salary range than the correlation in the lower salary ranges. Correlation plot of all players salaries against offensive statistics Low Salary Below $1 million Here we have a correlation plot between salary and batting statistics. This correlation plot is for players that are making below $1 million. We see in all of the plots that there is not a significant correlation between salary and batting statistics. It is, however, evident that players earning the lowest salaries show the lowest correlations. The overall trend for low salary players--which would be expected--is a negative correlation between salary and batting performance.