Arxiv:1606.01832V3 [Math.AC] 6 Sep 2017 K+1 Define the Quotient Ring Ak := A/A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Projective, Flat and Multiplication Modules

NEW ZEALAND JOURNAL OF MATHEMATICS Volume 31 (2002), 115-129 PROJECTIVE, FLAT AND MULTIPLICATION MODULES M a j i d M . A l i a n d D a v i d J. S m i t h (Received December 2001) Abstract. In this note all rings are commutative rings with identity and all modules are unital. We consider the behaviour of projective, flat and multipli cation modules under sums and tensor products. In particular, we prove that the tensor product of two multiplication modules is a multiplication module and under a certain condition the tensor product of a multiplication mod ule with a projective (resp. flat) module is a projective (resp. flat) module. W e investigate a theorem of P.F. Smith concerning the sum of multiplication modules and give a sufficient condition on a sum of a collection of modules to ensure that all these submodules are multiplication. W e then apply our result to give an alternative proof of a result of E l-B ast and Smith on external direct sums of multiplication modules. Introduction Let R be a commutative ring with identity and M a unital i?-module. Then M is called a multiplication module if every submodule N of M has the form IM for some ideal I of R [5]. Recall that an ideal A of R is called a multiplication ideal if for each ideal B of R with B C A there exists an ideal C of R such that B — AC. Thus multiplication ideals are multiplication modules. In particular, invertible ideals of R are multiplication modules. -

Modules Embedded in a Flat Module and Their Approximations

International Journal of Recent Development in Engineering and Technology Website: www.ijrdet.com (ISSN 2347 - 6435 (Online)) Volume 2, Issue 3, March 2014) Modules Embedded in a Flat Module and their Approximations Asma Zaffar1, Muhammad Rashid Kamal Ansari2 Department of Mathematics Sir Syed University of Engineering and Technology Karachi-75300S Abstract--An F- module is a module which is embedded in a Finally, the theory developed above is applied to flat flat module F. Modules embedded in a flat module approximations particularly the I (F)-flat approximations. demonstrate special generalized features. In some aspects We start with some necessary definitions. these modules resemble torsion free modules. This concept generalizes the concept of modules over IF rings and modules 1.1 Definition: Mmod-A is said to be a right F-module over rings whose injective hulls are flat. This study deals with if it is embedded in a flat module F ≠ M mod-A. Similar F-modules in a non-commutative scenario. A characterization definition holds for a left F-module. of F-modules in terms of torsion free modules is also given. Some results regarding the dual concept of homomorphic 1.2 Definition: A ring A is said to be an IF ring if its every images of flat modules are also obtained. Some possible injective module is flat [4]. applications of the theory developed above to I (F)-flat module approximation are also discussed. 1.3 Definition [Von Neumann]: A ring A is regular if, for each a A, and some another element x A we have axa Keyswords-- 16E, 13Dxx = a. -

Pure Exactness and Absolutely Flat Modules

Advances in Theoretical and Applied Mathematics. ISSN 0973-4554 Volume 9, Number 2 (2014), pp. 123-127 © Research India Publications http://www.ripublication.com Pure Exactness and Absolutely Flat Modules Duraivel T Department of Mathematics, Pondicherry University, Puducherry, India, 605014, E-mail: [email protected] Mangayarcarassy S Department of Mathematics, Pondicherry Engineering College, Puducherry, 605014, India, E-mail: [email protected] Athimoolam R Department of Mathematics, Pondicherry Engineering College, Puducherry, 605014, India, E-mail: [email protected] Abstract We show that an R-module M is absolutely flat over R if and only if M is R- flat and IM is a pure submodule of M, for every finitely generated ideal I. We also prove that N is a pure submodule of M and M is absolutely flat over R, if and only if both N and M/N are absolutely flat over R. AMS Subject Classification: 13C11. Keywords: Absolutely Flat Modules, Pure Submodule and Pure exact sequence. 1. Introduction Throughout this article, R denotes a commutative ring with identity and all modules are unitary. For standard terminology, the references are [1] and [7]. The concept of absolutely flat ring is extended to modules as absolutely flat modules, and studied in [2]. An R module M is said to be absolutely flat over R, if for every 2 Duraivel T, Mangayarcarassy S and Athimoolam R R-module N, M ⊗R N is flat R-module. Various characterizations of absolutely flat modules are studied in [2] and [4]. In this article, we show that an R-module M is absolutely flat over R if and only if for every finitely generated ideal I, IM is a pure submodule of M and M is R- flat. -

![Arxiv:2002.10139V1 [Math.AC]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5166/arxiv-2002-10139v1-math-ac-635166.webp)

Arxiv:2002.10139V1 [Math.AC]

SOME RESULTS ON PURE IDEALS AND TRACE IDEALS OF PROJECTIVE MODULES ABOLFAZL TARIZADEH Abstract. Let R be a commutative ring with the unit element. It is shown that an ideal I in R is pure if and only if Ann(f)+I = R for all f ∈ I. If J is the trace of a projective R-module M, we prove that J is generated by the “coordinates” of M and JM = M. These lead to a few new results and alternative proofs for some known results. 1. Introduction and Preliminaries The concept of the trace ideals of modules has been the subject of research by some mathematicians around late 50’s until late 70’s and has again been active in recent years (see, e.g. [3], [5], [7], [8], [9], [11], [18] and [19]). This paper deals with some results on the trace ideals of projective modules. We begin with a few results on pure ideals which are used in their comparison with trace ideals in the sequel. After a few preliminaries in the present section, in section 2 a new characterization of pure ideals is given (Theorem 2.1) which is followed by some corol- laries. Section 3 is devoted to the trace ideal of projective modules. Theorem 3.1 gives a characterization of the trace ideal of a projective module in terms of the ideal generated by the “coordinates” of the ele- ments of the module. This characterization enables us to deduce some new results on the trace ideal of projective modules like the statement arXiv:2002.10139v2 [math.AC] 13 Jul 2021 on the trace ideal of the tensor product of two modules for which one of them is projective (Corollary 3.6), and some alternative proofs for a few known results such as Corollary 3.5 which shows that the trace ideal of a projective module is a pure ideal. -

Commutative Algebra Example Sheet 2

Commutative Algebra Michaelmas 2010 Example Sheet 2 Recall that in this course all rings are commutative 1. Suppose that S is a m.c. subset of a ring A, and M is an A-module. Show that there is a natural isomorphism AS ⊗A M =∼ MS of AS-modules. Deduce that AS is a flat A-module. 2. Suppose that {Mi|i ∈ I} is a set of modules for a ring A. Show that M = Li∈I Mi is a flat A-module if and only if each Mi is a flat A-module. Deduce that projective modules are flat. 3. Show that an A-module is flat if every finitely generated submodule is flat. 4. Show that flatness is a local properties of modules. 5. Suppose that A is a ring and φ: An → Am is an isomorphism of A-modules. Must n = m? 6. Let A be a ring. Suppose that M is an A-module and f : M → M is an A-module map. (i) Show by considering the modules ker f n that if M is Noetherian as an A-module and f is surjective then f is an isomorphism (ii) Show that if M is Artinian as an A-module and f is injective then f is an isomorphism. 7. Let S be the subset of Z consisting of powers of some integer n ≥ 2. Show that the Z-module ZS/Z is Artinian but not Noetherian. 8. Show that C[X1, X2] has a C-subalgebra that is not a Noetherian ring. 9. Suppose that A is a Noetherian ring and A[[x]] is the ring of formal power series over A. -

TENSOR PRODUCTS Balanced Maps. Note. One Can Think of a Balanced

TENSOR PRODUCTS Balanced Maps. Note. One can think of a balanced map β : L × M → G as a multiplication taking its values in G. If instead of β(`; m) we write simply `m (a notation which is often undesirable) the rules simply state that this multiplication should be distributive and associative with respect to the scalar multiplication on the modules. I. e. (`1 + `2)m = `1m + `2m `(m1 + m2)=`m1 + `m2; and (`r)m = `(rm): There are a number of obvious examples of balanced maps. (1) The ring multiplication itself is a balanced map R × R → R. (2) The scalar multiplication on a left R-module is a balanced map R × M → M . (3) If K , M ,andN are left R-modules and E =EndRMthen for δ ∈ EndR M and ' ∈ HomR(M; P) the product ϕδ is defined in the obvious way. This gives HomR(M; P) a natural structure as a right E-module. Analogously, HomR(K; M)isaleftE-moduleinanobviousway.ThereisanE-balanced map β :HomR(M; P) × HomR(K; M) → HomR(K; M)givenby( ;')7→ '. (4) If M and P are left R-modules and E =EndRM, then, as above, HomR(M; P) is a right E-module. Furthermore, M is a left E-module in an obvious way. We then get an E-balanced map HomR(M; P) × M → P by ('; m) 7→'(m). (5) A (distributive) multiplication on an abelian group G is a Z-balanced map G × G → G. It is interesting to note that in examples (1) through (4), the target space for the balancedmapisinfactanR-module, rather than merely an abelian group. -

Commutative Algebra

Commutative Algebra Andrew Kobin Spring 2016 / 2019 Contents Contents Contents 1 Preliminaries 1 1.1 Radicals . .1 1.2 Nakayama's Lemma and Consequences . .4 1.3 Localization . .5 1.4 Transcendence Degree . 10 2 Integral Dependence 14 2.1 Integral Extensions of Rings . 14 2.2 Integrality and Field Extensions . 18 2.3 Integrality, Ideals and Localization . 21 2.4 Normalization . 28 2.5 Valuation Rings . 32 2.6 Dimension and Transcendence Degree . 33 3 Noetherian and Artinian Rings 37 3.1 Ascending and Descending Chains . 37 3.2 Composition Series . 40 3.3 Noetherian Rings . 42 3.4 Primary Decomposition . 46 3.5 Artinian Rings . 53 3.6 Associated Primes . 56 4 Discrete Valuations and Dedekind Domains 60 4.1 Discrete Valuation Rings . 60 4.2 Dedekind Domains . 64 4.3 Fractional and Invertible Ideals . 65 4.4 The Class Group . 70 4.5 Dedekind Domains in Extensions . 72 5 Completion and Filtration 76 5.1 Topological Abelian Groups and Completion . 76 5.2 Inverse Limits . 78 5.3 Topological Rings and Module Filtrations . 82 5.4 Graded Rings and Modules . 84 6 Dimension Theory 89 6.1 Hilbert Functions . 89 6.2 Local Noetherian Rings . 94 6.3 Complete Local Rings . 98 7 Singularities 106 7.1 Derived Functors . 106 7.2 Regular Sequences and the Koszul Complex . 109 7.3 Projective Dimension . 114 i Contents Contents 7.4 Depth and Cohen-Macauley Rings . 118 7.5 Gorenstein Rings . 127 8 Algebraic Geometry 133 8.1 Affine Algebraic Varieties . 133 8.2 Morphisms of Affine Varieties . 142 8.3 Sheaves of Functions . -

Flat Modules We Recall Here Some Properties of Flat Modules As

Flat modules We recall here some properties of flat modules as exposed in Bourbaki, Alg´ebreCommutative, ch. 1. The aim of these pages is to expose the proofs of some of the characterizations of flat and faithfully flat modules given in Matsumura's book Commutative Algebra. This part is mainly devoted to the exposition of a proof of the following Theorem. Let A be a commutative ring with identity and E an A-module. The following conditions are equivalent α β (a) for any exact sequence of A-modules 0 ! M 0 / M / M 00 ! 0 , the sequence 0 1E ⊗α 1E ⊗β 00 0 ! E ⊗A M / E ⊗A M / E ⊗A M ! 0 is exact; ∼ (b) for any finitely generated ideal I of A, the sequence 0 ! E ⊗A I ! E ⊗A A = E is exact; 0 b1 1 0 x1 1 t Pr . r . r (c) If bx = i=1 bixi = 0 for some b = @ . A 2 A and x = @ . A 2 E , there exist a matrix br xr s t A 2 Mr×s(A) and y 2 E such that x = Ay and bA = 0. α β We recall that, for any A-module, N, and for any exact sequence 0 ! M 0 / M / M 00 ! 0 , one gets the exact sequence 0 1N ⊗α 1N ⊗β 00 N ⊗A M / N ⊗A M / N ⊗A M ! 0 : Moreover, if αM 0 is a direct summand in M (which is equivalent to the existence of a morphism πM ! M 0 0 1N ⊗α such that πα = 1M 0 ), then the morphism N ⊗A M / N ⊗A M is injective and the image of 1N ⊗ α is a direct summand in N ⊗A M. -

LECTURE 18 1. Flatness and Completion Let M Be an A-Module

LECTURE 18 1. Flatness and completion Let M be an A-module. We say that M is A-flat, respectively A-faithfully flat if, for all sequences of A-modules E → F → G, the sequence is exact implies, respectively is equivalent to, that the sequence E ⊗A M → F ⊗A M → G ⊗A M is exact. For an A-algebra B, we say that B is a flat A-algebra if it is flat as an A-module. A ring homomorphism f : A → B is called a flat homomorphism if B is an A-flat algebra. −1 We note that S A, with S a multiplicatively closed set, and A[x1,...,xn] are A-flat algebras. In fact any free A-module, including polynomial rings over A, are faithfully flat. Using the fact that the tensor product is right exact, we note that flatness can be checked by only considering exact sequences of A-modules of the type 0 → E → F . The following two propositions list some simple consequences of flatness and faithful flatness which can be proven easily by manipulating the definitions. Proposition 1.1. Let B be an A-algebra and M a B-module. Then (1) B is A-flat (respectivey A-faithfully flat) and M is B-flat (respectively B-faithfully flat) then M is A-flat (respectively A-faithfully flat); (2) M is B-faithfully flat and M is A-flat (respectively A-faithfully flat) then B is A-flat (respectively A-faithfully flat) . Proposition 1.2. Let B be an A-algebra and M an A-module. -

(AS) 2 Lecture 2. Sheaves: a Potpourri of Algebra, Analysis and Topology (UW) 11 Lecture 3

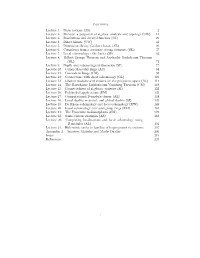

Contents Lecture 1. Basic notions (AS) 2 Lecture 2. Sheaves: a potpourri of algebra, analysis and topology (UW) 11 Lecture 3. Resolutions and derived functors (GL) 25 Lecture 4. Direct Limits (UW) 32 Lecture 5. Dimension theory, Gr¨obner bases (AL) 49 Lecture6. Complexesfromasequenceofringelements(GL) 57 Lecture7. Localcohomology-thebasics(SI) 63 Lecture 8. Hilbert Syzygy Theorem and Auslander-Buchsbaum Theorem (GL) 71 Lecture 9. Depth and cohomological dimension (SI) 77 Lecture 10. Cohen-Macaulay rings (AS) 84 Lecture 11. Gorenstein Rings (CM) 93 Lecture12. Connectionswithsheafcohomology(GL) 103 Lecture 13. Graded modules and sheaves on the projective space(AL) 114 Lecture 14. The Hartshorne-Lichtenbaum Vanishing Theorem (CM) 119 Lecture15. Connectednessofalgebraicvarieties(SI) 122 Lecture 16. Polyhedral applications (EM) 125 Lecture 17. Computational D-module theory (AL) 134 Lecture 18. Local duality revisited, and global duality (SI) 139 Lecture 19. De Rhamcohomologyand localcohomology(UW) 148 Lecture20. Localcohomologyoversemigrouprings(EM) 164 Lecture 21. The Frobenius endomorphism (CM) 175 Lecture 22. Some curious examples (AS) 183 Lecture 23. Computing localizations and local cohomology using D-modules (AL) 191 Lecture 24. Holonomic ranks in families of hypergeometric systems 197 Appendix A. Injective Modules and Matlis Duality 205 Index 215 References 221 1 2 Lecture 1. Basic notions (AS) Definition 1.1. Let R = K[x1,...,xn] be a polynomial ring in n variables over a field K, and consider polynomials f ,...,f R. Their zero set 1 m ∈ V = (α ,...,α ) Kn f (α ,...,α )=0,...,f (α ,...,α )=0 { 1 n ∈ | 1 1 n m 1 n } is an algebraic set in Kn. These are our basic objects of study, and include many familiar examples such as those listed below. -

Graduate Algebra: Noncommutative View

Graduate Algebra: Noncommutative View Louis Halle Rowen Graduate Studies in Mathematics Volume 91 American Mathematical Society http://dx.doi.org/10.1090/gsm/091 Graduate Algebra: Noncommutative View Graduate Algebra: Noncommutative View Louis Halle Rowen Graduate Studies in Mathematics Volume 91 American Mathematical Society Providence, Rhode Island Editorial Board Walter Craig Nikolai Ivanov Steven G. Krantz David Saltman (Chair) 2000 Mathematics Subject Classification. Primary 16–01, 17–01; Secondary 17Bxx, 20Cxx, 20Fxx. For additional information and updates on this book, visit www.ams.org/bookpages/gsm-91 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rowen, Louis Halle. Graduate algebra : commutative view / Louis Halle Rowen. p. cm. — (Graduate studies in mathematics, ISSN 1065-7339 : v. 73) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8218-0570-1 (alk. paper) 1. Commutative algebra. 2. Geometry, Algebraic. 3. Geometry, Affine. 4. Commutative rings. 5. Modules (Algebra). I. Title. II. Series. QA251.3.R677 2006 512.44—dc22 2006040790 Copying and reprinting. Individual readers of this publication, and nonprofit libraries acting for them, are permitted to make fair use of the material, such as to copy a chapter for use in teaching or research. Permission is granted to quote brief passages from this publication in reviews, provided the customary acknowledgment of the source is given. Republication, systematic copying, or multiple reproduction of any material in this publication is permitted only under license from the American Mathematical Society. Requests for such permission should be addressed to the Acquisitions Department, American Mathematical Society, 201 Charles Street, Providence, Rhode Island 02904-2294, USA. Requests can also be made by e-mail to [email protected]. -

Pure Submodules of Multiplication Modules

Beitr¨agezur Algebra und Geometrie Contributions to Algebra and Geometry Volume 45 (2004), No. 1, 61-74. Pure Submodules of Multiplication Modules Majid M. Ali David J. Smith Department of Mathematics, Sultan Qaboos University, Muscat, Oman e-mail: [email protected] Department of Mathematics, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand [email protected] Abstract. The purpose of this paper is to investigate pure submodules of multipli- cation modules. We introduce the concept of idempotent submodule generalizing idempotent ideal. We show that a submodule of a multiplication module with pure annihilator is pure if and only if it is multiplication and idempotent. Various properties and characterizations of pure submodules of multiplication modules are considered. We also give two descriptions for the trace of a pure submodule of a multiplication module. MSC 2000: 13C13, 13C05, 13A15 Keywords: multiplication module, pure submodule, idempotent submodule, flat module, projective module, radical of a module, trace of a module 0. Introduction Let R be a ring and M a unital R-module. Then M is called a multiplication module if for every submodule N of M there exists an ideal I of R such that N = IM, [3], [5] and [7]. An ideal I of R which is a multiplication module is called a multiplication ideal. Let R be a ring and K and L be submodules of an R-module M. The residual of K by L is [K : L], the set of all x in R such that xL ⊆ K. The annihilator of M, denoted by annM, is [0 : M]. For each m ∈ M, the annihilator of m, denoted by ann(m), is [0 : Rm].