A Botanist's View of the Big Tree1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thuja Plicata Has Many Traditional Uses, from the Manufacture of Rope to Waterproof Hats, Nappies and Other Kinds of Clothing

photograph © Daniel Mosquin Culturally modified tree. The bark of Thuja plicata has many traditional uses, from the manufacture of rope to waterproof hats, nappies and other kinds of clothing. Careful, modest, bark stripping has little effect on the health or longevity of trees. (see pages 24 to 35) photograph © Douglas Justice 24 Tree of the Year : Thuja plicata Donn ex D. Don In this year’s Tree of the Year article DOUGLAS JUSTICE writes an account of the western red-cedar or giant arborvitae (tree of life), a species of conifers that, for centuries has been central to the lives of people of the Northwest Coast of America. “In a small clearing in the forest, a young woman is in labour. Two women companions urge her to pull hard on the cedar bark rope tied to a nearby tree. The baby, born onto a newly made cedar bark mat, cries its arrival into the Northwest Coast world. Its cradle of firmly woven cedar root, with a mattress and covering of soft-shredded cedar bark, is ready. The young woman’s husband and his uncle are on the sea in a canoe carved from a single red-cedar log and are using paddles made from knot-free yellow cedar. When they reach the fishing ground that belongs to their family, the men set out a net of cedar bark twine weighted along one edge by stones lashed to it with strong, flexible cedar withes. Cedar wood floats support the net’s upper edge. Wearing a cedar bark hat, cape and skirt to protect her from the rain and INTERNATIONAL DENDROLOGY SOCIETY TREES Opposite, A grove of 80- to 100-year-old Thuja plicata in Queen Elizabeth Park, Vancouver. -

Distribution of Living Cupressaceae Reflects the Breakup of Pangea

Distribution of living Cupressaceae reflects the breakup of Pangea Kangshan Maoa,b,c,1, Richard I. Milnea,b,c,1, Libing Zhangd,e, Yanling Penga, Jianquan Liua,2, Philip Thomasc, Robert R. Millc, and Susanne S. Rennerf aState Key Laboratory of Grassland Agro-Ecosystem, School of Life Sciences, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, Gansu 730000, People’s Republic of China; bInstitute of Molecular Plant Sciences, School of Biological Sciences, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH9 3JH, United Kingdom; cRoyal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH3 5LR, Scotland, United Kingdom; dChengdu Institute of Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Chengdu, Sichuan 610041, People’s Republic of China; eMissouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO 63166; fSystematic Botany and Mycology, Department of Biology, University of Munich, 80638 Munich, Germany Edited by Charles C. Davis, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, and accepted by the Editorial Board March 21, 2012 (received for review September 2, 2011) Most extant genus-level radiations in gymnosperms are of Oligocene occur on all continents except Antarctica and comprise 162 species age or younger, reflecting widespread extinction during climate in 32 genera (see Table S2 for subfamilies, genera, and species cooling at the Oligocene/Miocene boundary [∼23 million years ago numbers). The family has a well-studied fossil record going back (Ma)]. Recent biogeographic studies have revealed many instances of to the Jurassic (32–36). Using ancient fossils to calibrate genetic long-distance dispersal in gymnospermsaswellasinangiosperms. distances in molecular phylogenies can be problematic, because the Acting together, extinction and long-distance dispersal are likely to older a fossil is, the more likely it is to represent an extinct lineage erase historical biogeographic signals. -

1 Paleobotanical Proxies for Early Eocene Climates and Ecosystems in Northern North 2 America from Mid to High Latitudes 3 4 Christopher K

https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-2020-32 Preprint. Discussion started: 24 March 2020 c Author(s) 2020. CC BY 4.0 License. 1 Paleobotanical proxies for early Eocene climates and ecosystems in northern North 2 America from mid to high latitudes 3 4 Christopher K. West1, David R. Greenwood2, Tammo Reichgelt3, Alexander J. Lowe4, Janelle M. 5 Vachon2, and James F. Basinger1. 6 1 Dept. of Geological Sciences, University of Saskatchewan, 114 Science Place, Saskatoon, 7 Saskatchewan, S7N 5E2, Canada. 8 2 Dept. of Biology, Brandon University, 270-18th Street, Brandon, Manitoba R7A 6A9, Canada. 9 3 Department of Geosciences, University of Connecticut, Beach Hall, 354 Mansfield Rd #207, 10 Storrs, CT 06269, U.S.A. 11 4 Dept. of Biology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195-1800, U.S.A. 12 13 Correspondence to: C.K West ([email protected]) 14 15 Abstract. Early Eocene climates were globally warm, with ice-free conditions at both poles. Early 16 Eocene polar landmasses supported extensive forest ecosystems of a primarily temperate biota, 17 but also with abundant thermophilic elements such as crocodilians, and mesothermic taxodioid 18 conifers and angiosperms. The globally warm early Eocene was punctuated by geologically brief 19 hyperthermals such as the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), culminating in the 20 Early Eocene Climatic Optimum (EECO), during which the range of thermophilic plants such as 21 palms extended into the Arctic. Climate models have struggled to reproduce early Eocene Arctic 22 warm winters and high precipitation, with models invoking a variety of mechanisms, from 23 atmospheric CO2 levels that are unsupported by proxy evidence, to the role of an enhanced 24 hydrological cycle to reproduce winters that experienced no direct solar energy input yet remained 25 wet and above freezing. -

Growth and Colonization of Western Redcedar by Vesicular-Arbuscular Mycorrhizae in Fumigated and Nonfumigated Nursery Beds

Tree Planter's Notes, Volume 42, No. 4 (1991) Growth and Colonization of Western Redcedar by Vesicular-Arbuscular Mycorrhizae in Fumigated and Nonfumigated Nursery Beds S. M. Berch, E. Deom, and T. Willingdon Assistant professor and research assistant, Department of Soil Science, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, and manager, Surrey Nursery, British Columbia Ministry of Forests, Surrey, BC Western redcedar (Thuja plicata Donn ex D. Don) VAM. Positive growth responses of up to 20 times the seedlings were grown in a bareroot nursery bed that had nonmycorrhizal controls occurred under conditions of limited been fumigated with methyl bromide. Seedlings grown in soil phosphorus. Incense-cedar, redwood, and giant sequoia fumigated beds were stunted and had purple foliage. seedlings in northern California nursery beds are routinely Microscopic examination showed that roots from these inoculated with Glomus sp. (Adams et al. 1990), as seedlings were poorly colonized by mycorrhizae, and only by experience has shown that the absence of VAM after soil fine vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizae. In contrast, roots from fumigation leads to phosphorus deficiency and poor growth. seedlings grown in non-fumigated beds had larger shoots and When western redcedars in fumigated transplant beds at green foliage and were highly colonized by both fine and the British Columbia Ministry of Forest's Surrey Nursery coarse vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizae. Tree Planters' began to show signs of phosphorus deficiency, a deficiency Notes 42(4):14-16; 1991. of mycorrhizal colonization was suspected. Many studies have demonstrated improved P status of VAM-inoculated Species of cypress (Cupressaceae) and yew plants (see Harley and Smith 1983). -

Falmouth's Great Gardens of Empire: Wealth and Power in Nineteenth

Falmouth’s Great Gardens of Empire: Wealth and power in nineteenth century horticulture By Megan Oldcorn TROZE The Online Journal of the National Maritime Museum Cornwall www.nmmc.co.uk Cornwall Online Journal Museum Maritime The of National the Month 2015 Volume 6 Number 2 TROZE Troze is the journal of the National Maritime Museum Cornwall whose mission is to promote an understanding of small boats and their place in people’s lives, and of the maritime history of Cornwall. ‘Troze: the sound made by water about the bows of a boat in motion’ From R. Morton Nance, A Glossary of Cornish Sea Words Editorial Board Editor Dr. Cathryn Pearce Dr. Helen Doe Captain George Hogg RN, National Maritime Museum Cornwall Dr Alston Kennerley, University of Plymouth Tony Pawlyn, Head of Library, National Maritime Museum Cornwall Professor Philip Payton, Institute of Cornish Studies, University of Exeter Dr Nigel Rigby, National Maritime Museum Dr Martin Wilcox, Maritime Historical Studies Centre, University of Hull We welcome article submissions on any aspect relating to our mission. Please contact the editor at [email protected] or National Maritime Museum Cornwall Discovery Quay Falmouth Cornwall TR11 3QY United Kingdom © 2015 National Maritime Museum Cornwall and Megan Oldcorn Megan Oldcorn Megan Oldcorn is a PhD student at Falmouth University. Her research project investigates Falmouth and the role it played in the British Empire during the period 1800-1850. Falmouth’s Great Gardens of Empire: Wealth and power in nineteenth century horticulture Megan Oldcorn The woods rising on the opposite side of the stream belong to Carclew, the seat of Sir Charles Lemon, Bart., M. -

Extinction, Transoceanic Dispersal, Adaptation and Rediversification

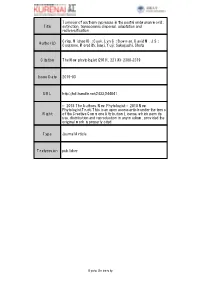

Turnover of southern cypresses in the post-Gondwanan world: Title extinction, transoceanic dispersal, adaptation and rediversification Crisp, Michael D.; Cook, Lyn G.; Bowman, David M. J. S.; Author(s) Cosgrove, Meredith; Isagi, Yuji; Sakaguchi, Shota Citation The New phytologist (2019), 221(4): 2308-2319 Issue Date 2019-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/244041 © 2018 The Authors. New Phytologist © 2018 New Phytologist Trust; This is an open access article under the terms Right of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University Research Turnover of southern cypresses in the post-Gondwanan world: extinction, transoceanic dispersal, adaptation and rediversification Michael D. Crisp1 , Lyn G. Cook2 , David M. J. S. Bowman3 , Meredith Cosgrove1, Yuji Isagi4 and Shota Sakaguchi5 1Research School of Biology, The Australian National University, RN Robertson Building, 46 Sullivans Creek Road, Acton (Canberra), ACT 2601, Australia; 2School of Biological Sciences, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Qld 4072, Australia; 3School of Natural Sciences, The University of Tasmania, Private Bag 55, Hobart, Tas 7001, Australia; 4Graduate School of Agriculture, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan; 5Graduate School of Human and Environmental Studies, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan Summary Author for correspondence: Cupressaceae subfamily Callitroideae has been an important exemplar for vicariance bio- Michael D. Crisp geography, but its history is more than just disjunctions resulting from continental drift. We Tel: +61 2 6125 2882 combine fossil and molecular data to better assess its extinction and, sometimes, rediversifica- Email: [email protected] tion after past global change. -

Metasequoia Glyptostroboides: Fifty Years of Growth in North America John E

Metasequoia glyptostroboides: Fifty Years of Growth in North America john E. Kuser half a century after Metasequoia have grown to remarkable size in the relatively ) glyptostroboides was introduced into short time of fifty years. Perhaps the largest ow,~ the West from China, the dawn red- overall is a tree at Bailey Arboretum, in Locust woods produced from these seeds rank among Valley, New York, which in late August 1998 the temperate zone’s finest trees. Some of them measured 104 feet in height, 17 feet 8 inches in breast-high girth, and 60 feet in crownspread. Several trees in a grove alongside a small stream in Broadmeade Park, Princeton, New Jersey, are now over 125 feet tall, although not as large in circumference or crown as the Bailey tree. In favorable areas, many others are over 100 feet in height and 12 feet in girth. In 1952 a visiting scholar from China, Dr. Hui-Lin Li, planted dawn redwoods from a later seed shipment along Wissahickon Creek in the University of Pennsylvania’s Morris Arboretum in Philadelphia. Li knew the conditions under which Metasequoia did best in its native range: in full sunshine on stream- side sites, preferably sloping south, with water available all summer and season- able variations in temperature like those found on our East Coast-warm sum- mers and cold winters. Today, Li’s grove beside the Wissahickon inspires awe; its trees reach as high as 113 feet and mea- sure up to 12 feet 6 inches in girth. Large dawn redwoods now occur as far north as Boston, Massachusetts, and Syracuse, New York, and as far south as Atlanta, Georgia, and Huntsville, Alabama, and are found in all the states between. -

Plant List 2020/21

PLANTwww.ctsplants.com LIST 2020/21 1 CONTENTS Beckheath Nursery 2 01590 612198 CONTENTS CONTENTS Introduction to Chichester Trees and Shrubs 4 Office Contacts 9 How to Order 10 Delivery Charges 13 New Plant Introductions 14 Shrubs 26 Trees 57 Hedging 63 Climbers 67 Clematis 72 Perennials 77 Common Herbs & Edibles 114 Bamboo 115 Grasses 116 Ferns 119 Roses 121 Terms and Conditions 129 Nursery Maps 130 www.ctsplants.com 3 ABOUT ABOUT CHICHESTER Welcome to our new 2020/21 Plant List Chichester Trees and Shrubs Ltd was originally founded as a tree nursery in 1976 by James Chichester. Over the years it has evolved. We now grow an extensive range of perennials, shrubs, specimen stock, grasses, ferns, trees, fruit, roses and climbers over three nursery sites. We also have a very efficient network of suppliers and specialist growers, and source many plants not listed in our main catalogue. As a wholesale nursery we are geared up to professional members of the trade, however we can supply private clients under strictly wholesale terms. Orders must have a minimum value of £300.00 for a delivery. Smaller orders can be arranged for collection from one of our nursery sites with at least 48 hours notice. If you do not see the stock you are looking for please email us at [email protected]. We have a wide network of suppliers in the UK and Europe and may be able to supply what you are looking for. 4 01590 612198 ABOUT www.ctsplants.com 5 ABOUT RHS – AWARD OF GARDEN MERIT We have marked items in the catalogue with the RHS Award of Garden Merit (AGM). -

Metasequoia Dawn Redwood a Truly Beautiful Tree

Metasequoia Dawn Redwood A Truly Beautiful Tree Metasequoia glyptostroboides is considered to be a living fossil as it is the only remaining species of a genus that was widespread in the geological past. In 1941 it was discovered in Hubei, China. In 1948 the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University sent an expedition to collect seed, which was distributed to universities and botanical gardens worldwide for growth trials. Seedlings were raised in New Zealand and trees can be seen in Christchurch Botanical Gardens, Eastwoodhill and Queens Gardens, Nelson. A number of natural Metasequoia populations exist in the wetlands and valleys of Lichuan County, Hubei, mostly as small groups. The largest contains 5400 trees. It is an excellent tall growing deciduous tree to complement evergreens in wetlands, stream edge plantings to control slips, and to prevent erosion in damp valley bottoms where other forestry trees fail to grow. Spring growth is a fresh bright green and in autumn the foliage turns a A fast growing deciduous conifer, red coppery brown making a great display. with a straight trunk, numerous It is also a most attractive winter branch silhouette. While the foliage is a similiar colour in autumn to that of swamp cypress (Taxodium), it is a branches and a tall conical crown, much taller erect growing tree, though both species thrive in moist soil growing to 45 metres in height and conditions. We import our seed from China and the uniformity of the seedling one metre in diameter. crop is most impressive. The timber has been used in boat building. Abies vejari 20 years old on left 14 years old on right Abies Silver Firs These dramatic conical shaped conifers make a great statement in the landscape, long-lived and withstanding the elements. -

Callitris Forests and Woodlands

NVIS Fact sheet MVG 7 – Callitris forests and woodlands Australia’s native vegetation is a rich and fundamental Overview element of our natural heritage. It binds and nourishes our ancient soils; shelters and sustains wildlife, protects Typically, vegetation areas classified under MVG 7 – streams, wetlands, estuaries, and coastlines; and absorbs Callitris forests and woodlands: carbon dioxide while emitting oxygen. The National • comprise pure stands of Callitris that are restricted and Vegetation Information System (NVIS) has been developed generally occur in the semi-arid regions of Australia and maintained by all Australian governments to provide • in most cases Callitris species are a co-dominant a national picture that captures and explains the broad or occasional species in other vegetation groups, diversity of our native vegetation. particularly eucalypt woodlands and forests in temperate This is part of a series of fact sheets which the Australian semi-arid and sub-humid climates. After disturbance, Government developed based on NVIS Version 4.2 data to Callitris may regenerate in high densities and become provide detailed descriptions of the major vegetation groups a dominant member of a mixed canopy layer. Some of (MVGs) and other MVG types. The series is comprised of these modified communities are mapped asCallitris a fact sheet for each of the 25 MVGs to inform their use by forests or woodlands planners and policy makers. An additional eight MVGs are • are generally dominated by a herbaceous understorey available outlining other MVG types. with only a few shrubs • in New South Wales Callitris has been an important For more information on these fact sheets, including forestry timber and large monocultures have been its limitations and caveats related to its use, please see: encouraged for this purpose ‘Introduction to the Major Vegetation Group (MVG) fact sheets’. -

Cupressaceae Calocedrus Decurrens Incense Cedar

Cupressaceae Calocedrus decurrens incense cedar Sight ID characteristics • scale leaves lustrous, decurrent, much longer than wide • laterals nearly enclosing facials • seed cone with 3 pairs of scale/bract and one central 11 NOTES AND SKETCHES 12 Cupressaceae Chamaecyparis lawsoniana Port Orford cedar Sight ID characteristics • scale leaves with glaucous bloom • tips of laterals on older stems diverging from branch (not always too obvious) • prominent white “x” pattern on underside of branchlets • globose seed cones with 6-8 peltate cone scales – no boss on apophysis 13 NOTES AND SKETCHES 14 Cupressaceae Chamaecyparis thyoides Atlantic white cedar Sight ID characteristics • branchlets slender, irregularly arranged (not in flattened sprays). • scale leaves blue-green with white margins, glandular on back • laterals with pointed, spreading tips, facials closely appressed • bark fibrous, ash-gray • globose seed cones 1/4, 4-5 scales, apophysis armed with central boss, blue/purple and glaucous when young, maturing in fall to red-brown 15 NOTES AND SKETCHES 16 Cupressaceae Callitropsis nootkatensis Alaska yellow cedar Sight ID characteristics • branchlets very droopy • scale leaves more or less glabrous – little glaucescence • globose seed cones with 6-8 peltate cone scales – prominent boss on apophysis • tips of laterals tightly appressed to stem (mostly) – even on older foliage (not always the best character!) 15 NOTES AND SKETCHES 16 Cupressaceae Taxodium distichum bald cypress Sight ID characteristics • buttressed trunks and knees • leaves -

Morphology and Morphogenesis of the Seed Cones of the Cupressaceae - Part II Cupressoideae

1 2 Bull. CCP 4 (2): 51-78. (10.2015) A. Jagel & V.M. Dörken Morphology and morphogenesis of the seed cones of the Cupressaceae - part II Cupressoideae Summary The cone morphology of the Cupressoideae genera Calocedrus, Thuja, Thujopsis, Chamaecyparis, Fokienia, Platycladus, Microbiota, Tetraclinis, Cupressus and Juniperus are presented in young stages, at pollination time as well as at maturity. Typical cone diagrams were drawn for each genus. In contrast to the taxodiaceous Cupressaceae, in Cupressoideae outgrowths of the seed-scale do not exist; the seed scale is completely reduced to the ovules, inserted in the axil of the cone scale. The cone scale represents the bract scale and is not a bract- /seed scale complex as is often postulated. Especially within the strongly derived groups of the Cupressoideae an increased number of ovules and the appearance of more than one row of ovules occurs. The ovules in a row develop centripetally. Each row represents one of ascending accessory shoots. Within a cone the ovules develop from proximal to distal. Within the Cupressoideae a distinct tendency can be observed shifting the fertile zone in distal parts of the cone by reducing sterile elements. In some of the most derived taxa the ovules are no longer (only) inserted axillary, but (additionally) terminal at the end of the cone axis or they alternate to the terminal cone scales (Microbiota, Tetraclinis, Juniperus). Such non-axillary ovules could be regarded as derived from axillary ones (Microbiota) or they develop directly from the apical meristem and represent elements of a terminal short-shoot (Tetraclinis, Juniperus).