Testimony of Michael Waldman President

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Working Group Report and Nine Policy Recommendations by the PES Working Group on Fighting Voter Abstention

Working Group report and nine policy recommendations by the PES Working Group on fighting voter abstention Chaired by PES Presidency Member Mr. Raymond Johansen Report adopted by the PES Presidency on 17 March 2017 2 Content: 1. Summary…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….4 2. Summary of the nine policy recommendations…………………………………………………………..………6 3. European elections, national rules….…………………………………………………………………………………. 7 4. The Millennial generation and strategies to connect…………..…………………………………………… 13 5. Seven key issues with nine policy recommendations…………..…………………………………………… 20 Early voting……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….20 Access to polling stations…………………………………………………………………………………………………. 22 Age limits for voting and standing for election…………………………………………………………………. 23 Voting registration as a precondition…………………………………………………………………………….... 25 Voting from abroad…………………………………………………………………………………………………………..26 Safe electronic systems of voting……………………………………………………………………………………… 28 Citizens’ awareness…………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 30 Annexes Summary of the PES working group`s mandate and activity………………………………………..……33 References……..…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………41 3 SUMMARY The labour movement fought and won the right to vote for all. Therefore we in particular are concerned about the trend of too many voters not using the fundamental democratic right to vote. Since the European Parliament was first elected in 1979, we have seen turnout steadily decrease. Turnout in 2014 reached a historic low. We must -

Pre-Election Toplines: Oregon Early Voting Information Center 2020 Pre

Oregon RV Poll October 22 - October 31, 2020 Sample 2,008 Oregon Registered Voters Margin of Error ±2.8% 1. All things considered, do you think Oregon is headed in the right direction, or is it off on the wrong track? Right direction . 42% Wrong track . 47% Don’t know . 11% 2. Have you, or has anyone in your household, experienced a loss of employment income since the COVID-19 pandemic began? Yes .....................................................................................37% No ......................................................................................63% 3. How worried are you about your personal financial situation? Veryworried ............................................................................17% Somewhat worried . .36% Not too worried . 33% Not at all worried . 13% Don’tknow ..............................................................................0% 4. How worried are you about the spread of COVID-19 in your community? Veryworried ............................................................................35% Somewhat worried . .34% Not too worried . 19% Not at all worried . 12% Don’tknow ..............................................................................0% 5. How much confidence do you have in the following people and institutions? A great deal of Only some Hardly any No confidence confidence confidence confidence Don’t know Governor Kate Brown 32% 22% 9% 35% 2% Secretary of State Bev Clarno 18% 24% 12% 16% 30% The Oregon State Legislature 14% 37% 21% 21% 8% The officials who run Oregon state elections 42% 27% 12% 12% 7% The officials who run elections in [COUNTY NAME] 45% 30% 10% 7% 8% The United States Postal Service 39% 40% 12% 7% 2% 1 Oregon RV Poll October 22 - October 31, 2020 6. Which of the following best describes you? I definitely will not vote in the November general election . 5% I will probably not vote in the November general election . -

Black Box Voting Ballot Tampering in the 21St Century

This free internet version is available at www.BlackBoxVoting.org Black Box Voting — © 2004 Bev Harris Rights reserved to Talion Publishing/ Black Box Voting ISBN 1-890916-90-0. You can purchase copies of this book at www.Amazon.com. Black Box Voting Ballot Tampering in the 21st Century By Bev Harris Talion Publishing / Black Box Voting This free internet version is available at www.BlackBoxVoting.org Contents © 2004 by Bev Harris ISBN 1-890916-90-0 Jan. 2004 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form whatsoever except as provided for by U.S. copyright law. For information on this book and the investigation into the voting machine industry, please go to: www.blackboxvoting.org Black Box Voting 330 SW 43rd St PMB K-547 • Renton, WA • 98055 Fax: 425-228-3965 • [email protected] • Tel. 425-228-7131 This free internet version is available at www.BlackBoxVoting.org Black Box Voting © 2004 Bev Harris • ISBN 1-890916-90-0 Dedication First of all, thank you Lord. I dedicate this work to my husband, Sonny, my rock and my mentor, who tolerated being ignored and bored and galled by this thing every day for a year, and without fail, stood fast with affection and support and encouragement. He must be nuts. And to my father, who fought and took a hit in Germany, who lived through Hitler and saw first-hand what can happen when a country gets suckered out of democracy. And to my sweet mother, whose an- cestors hosted a stop on the Underground Railroad, who gets that disapproving look on her face when people don’t do the right thing. -

Fresh Perspectives NCDOT, State Parks to Coordinate on Pedestrian, Bike Bridge For

Starts Tonight Poems Galore •SCHS opens softball play- offs with lop-sided victory Today’s issue includes over Red Springs. •Hornets the winners and win- sweep Jiggs Powers Tour- ning poems of the A.R. nament baseball, softball Ammons Poetry Con- championships. test. See page 1-C. Sports See page 3-A See page 1-B. ThePublished News since 1890 every Monday and Thursday Reporterfor the County of Columbus and her people. Thursday, May 12, 2016 Fresh perspectives County school Volume 125, Number 91 consolidation, Whiteville, North Carolina 75 Cents district merger talks emerge at Inside county meeting 3-A By NICOLE CARTRETTE News Editor •Top teacher pro- motes reading, paren- Columbus County school officials are ex- tal involvement. pected to ask Columbus County Commission- ers Monday to endorse a $70 million plan to consolidate seven schools into three. 4-A The comprehensive study drafted by Szotak •Long-delayed Design of Chapel Hill was among top discus- murder trial sions at the Columbus County Board of Com- set to begin here missioners annual planning session held at Southeastern Community College Tuesday Monday. night. While jobs and economic development, implementation of an additional phase of a Next Issue county salary study, wellness and recreation talks and expansion of natural gas, water and sewer were among topics discussed, the board spent a good portion of the four-hour session talking about school construction. No plans The commissioners tentatively agreed that they had no plans to take action on the propos- al Monday night and hinted at wanting more details about coming to an agreement with Photo by GRANT MERRITT the school board about funding the proposal. -

Description: All in - Final Picture Lock – Full Film - 200726

DESCRIPTION: ALL IN - FINAL PICTURE LOCK – FULL FILM - 200726 [01:00:31:00] [TITLE: November 6, 2018] ANCHORWOMAN: It might be a race for the governor’s mansion in Georgia, but this is one that the entire country is watching. ANCHORWOMAN: And if ever one vote counted it certainly is going to count in this particular race. [01:00:46:00] [TITLE: The race for Georgia governor is between Democrat Stacey Abrams and Republican Brian Kemp.] [If elected, Abrams would become the nation’s first female African American governor.] CROWD: Stacey! Stacey! Stacey! Stacey! Stacey! ANCHORWOMAN: The controversy surrounding Georgia’s governor race is not dying down. Both candidates dug in today. ANCHORWOMAN: Republican Brian Kemp and Democrat Stacey Abrams are locked in a virtual dead heat. ANCHORWOMAN: Everybody wants to know what’s happening in Georgia, still a toss up there, as we’re waiting for a number of votes to come in. They believe there are tens of thousands of absentee ballots that have not yet been counted. ANCHORWOMAN: Voter suppression has become a national talking point and Brian Kemp has become a focal point. [01:01:27:00] LAUREN: All of the votes in this race have not been counted. 1 BRIAN KEMP: On Tuesday, as you know, we earned a clear and convincing, uh, victory at the ballot box and today we’re beginning the transition process. ANCHORMAN: Kemp was leading Democratic opponent Stacey Abrams by a narrow margin and it grew more and more narrow in the days following the election. Abrams filed multiple lawsuits, but ultimately dropped out of the race. -

Absentee Voting and Vote by Mail

CHapteR 7 ABSENTEE VOTING AND VOTE BY MAIL Introduction some States the request is valid for one or more years. In other States, an application must be com- Ballots are cast by mail in every State, however, the pleted and submitted for each election. management of absentee voting and vote by mail varies throughout the nation, based on State law. Vote by Mail—all votes are cast by mail. Currently, There are many similarities between the two since Oregon is the only vote by mail State; however, both involve transmitting paper ballots to voters and several States allow all-mail ballot voting options receiving voted ballots at a central election office for ballot initiatives. by a specified date. Many of the internal procedures for preparation and mailing of ballots, ballot recep- Ballot Preparation and Mailing tion, ballot tabulation and security are similar when One of the first steps in preparing to issue ballots applied to all ballots cast by mail. by mail is to determine personnel and facility and The differences relate to State laws, rules and supply needs. regulations that control which voters can request a ballot by mail and specific procedures that must be Facility Needs: followed to request a ballot by mail. Rules for when Adequate secure space for packaging the outgoing ballot requests must be received, when ballots are ballot envelopes should be reviewed prior to every mailed to voters, and when voted ballots must be election, based on the expected quantity of ballots returned to the election official—all defer according to be processed. Depending upon the number of ballot to State law. -

Fourth Annual Conference

1993] FOURTH ANNUAL CONFERENCE Again, I simply return to the proposition which the court has ac- cepted in other cases that the pharmaceutical company has a legitimate entitlement. The company performed a very lawful, purposeful activity in doing the research and developing the patents of the drugs. I do not see where a nuisance exception has any relevance in this scenario. It is not a nuisance to create this drug, and it is not a nui- sance to operate a drug production plant. I do not want to be trivial about this at all, but it is very easy to give away what you do not own. In my view, this is what happens in a lot of these cases. Some great lofty public good is determined by a state, county, or Federal Government, and any activity that impedes it is au- tomatically declared a nuisance. So I would say that the Fifth Amend- ment is not restricted to land uses. It's a property clause. Ms. Jones: I would like to thank both of our panelists. THE COUNCIL ON COMPETITIVENESS AND REGULATORY REVIEW: A "KINDER, GENTLER" APPROACH TO REGULATION? Delissa Ridgway* Jim Tozzi** Michael Waldman*** Ms. Ridgway: I am Delissa Ridgway. I am delighted to be able to present the last panel this morning. We have two distinguished com- mentators to address one of the hottest topics in administrative law to- day, the President's Council on Competitiveness.1 74 The fundamental * Ms. Ridgway is counsel to the Washington, D.C., law firm of Shaw, Pittman, Potts & Trowbridge, where she has specialized in the area of nuclear energy law since 1979. -

Evidence from Norway How Do Political Rights Influence Immigrant

Voting Rights and Immigrant Incorporation: Evidence from Norway JEREMY FERWERDA, HENNING FINSERAAS AND JOHANNES BERGH ∗ How do political rights influence immigrant integration? In this study, we demonstrate that the timing of voting rights extension plays a key role in fos- tering political incorporation. In Norway, non-citizens gain eligibility to vote in local elections after three years of residency. Drawing on individual-level registry data and a regression discontinuity design, we leverage the exoge- nous timing of elections relative to the start of residency periods to identify the effect of early access to political institutions. We find that immigrants who received early access were more likely to participate in subsequent elec- ∗ Jeremy Ferwerda, Dartmouth College, Department of Government 202 Silsby Hall Hanover, New Hampshire 03755, USA, email: [email protected]. Henning Finseraas, Institute for Social Research, P.box 3233 Elisenberg, 0208 Oslo, Norway e-mail: henning.fi[email protected]. Johannes Bergh, Institute for Social Research, P.box 3233 Elisenberg, 0208 Oslo, Norway e-mail: [email protected]. We would like to thank Dag Arne Christensen, Jens Hainmueller, Axel West Pedersen, Victoria Shineman, Øyvind Skorge, and participants at the 6th annual workshop on Comparative Ap- proaches to Immigration, Ethnicity, and Integration, Yale, June 2016, the 6th annual general conference of the European Political Science Association in Brussels, June 2016, and the Politi- cal Behavior workshop in Toronto, November 2016 for useful comments and suggestions. Grant numbers 227072 (Research Council of Norway) and 236786 (Research Council of Norway) are acknowledged. Voting Rights and Immigrant Incorporation 2 toral contests, with the strongest effects visible among immigrants from dic- tatorships and weak democracies. -

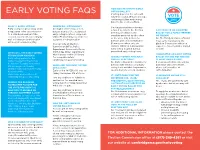

Early Voting Faqs

HOW DO I RETURN MY EARLY EARLY VOTING FAQS VOTING BALLOT? If voting in person the voter will return the sealed affidavit envelope containing his/her early voting ballot to the election official. WHAT IS EARLY VOTING? WHERE DO I VOTE EARLY? If voting by mail the voter may Early voting is a process by which All eligible voters may vote in return it by mail to the Election CAN I PICK UP AN ABSENTEE a registered voter can vote prior person at any of the designated Commission office in the BALLOT FOR A FAMILY MEMBER to a scheduled biennial state early voting locations or by mail. envelope provided by this office OR FRIEND? election. Voters can vote early by Unlike Election Day voters are not or the voter may deliver the No. The family member or friend mail or in-person and the ballot assigned a voting location. ballot in person to the Election must come in person to the will be cast on Election Day. You can vote at: Election Commission office or to an Election Commission office or Commission Office, Police election official at a designated request to have the ballot mailed Department Community Room, early voting location during to them. Cambridge Water Department, prescribed early voting hours. WHEN WILL THE EARLY VOTING Main Library, or O’Neill Library I REQUESTED AN EARLY VOTING PERIOD BEGIN AND END? IS EARLY VOTING AVAILABLE BALLOT BUT DID NOT RECEIVE Early voting period for the For complete details: FOR ALL ELECTIONS? IT, WHAT SHOULD I DO? State/Presidential Election to cambridgema.gov/earlyvoting No. -

Compulsory Voting and Political Participation: Empirical Evidence from Austria

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Gaebler, Stefanie; Potrafke, Niklas; Rösel, Felix Working Paper Compulsory voting and political participation: Empirical evidence from Austria ifo Working Paper, No. 315 Provided in Cooperation with: Ifo Institute – Leibniz Institute for Economic Research at the University of Munich Suggested Citation: Gaebler, Stefanie; Potrafke, Niklas; Rösel, Felix (2019) : Compulsory voting and political participation: Empirical evidence from Austria, ifo Working Paper, No. 315, ifo Institute - Leibniz Institute for Economic Research at the University of Munich, Munich This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/213592 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have -

Resolution Proposing an Amendment to the State Constitution to Allow for Early Voting

OFFICE OF LEGISLATIVE RESEARCH PUBLIC ACT SUMMARY RA 19-1—sHJ 161 Government Administration and Elections Committee RESOLUTION PROPOSING AN AMENDMENT TO THE STATE CONSTITUTION TO ALLOW FOR EARLY VOTING SUMMARY: This resolution proposes a constitutional amendment to authorize the General Assembly to provide by law for in-person, early voting before an election or referendum. It also removes the requirement that a duplicate list of election results for state officers and state legislators, which under the constitution must be sent to the secretary of the state within 10 days after the election, be submitted under seal. (Under the General Statutes, moderators must send a duplicate list of election results to the secretary (1) electronically within 48 hours after the election and (2) under seal within three days after the election (CGS § 9- 314).) The ballot designation to be used when the amendment is presented at the general election is: “Shall the Constitution of the State be amended to permit the General Assembly to provide for early voting?” EFFECTIVE DATE: The resolution will be referred to the 2021 session of the legislature. If it passes in that session by a majority of the membership of each house, it will appear on the 2022 general election ballot. If a majority of those voting on the amendment in the general election approves it, the amendment will become part of the state constitution. CURRENT CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS The state constitution sets the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November in specified years as the day of election for legislative and statewide offices. It currently requires election officials to receive and declare votes on this day to elect state legislators and state officers, with one exception. -

Efficiency, Equity, and Timing of Voting Mechanisms

American Political Science Review Vol. 101, No. 3 August 2007 DOI: 10.1017/S0003055407070281 Efficiency, Equity, and Timing of Voting Mechanisms MARCO BATTAGLINI Princeton University REBECCA MORTON New York University THOMAS PALFREY California Institute of Technology e compare the behavior of voters under simultaneous and sequential voting rules when voting is costly and information is incomplete. In many political institutions, ranging from small W committees to mass elections, voting is sequential, which allows some voters to know the choices of earlier voters. For a stylized model, we generate a variety of predictions about the relative efficiency and participation equity of these two systems, which we test using controlled laboratory experiments. Most of the qualitative predictions are supported by the data, but there are significant departures from the predicted equilibrium strategies, in both the sequential and the simultaneous voting games. We find a tradeoff between information aggregation, efficiency, and equity in sequential voting: a sequential voting rule aggregates information better than simultaneous voting and is more efficient in some information environments, but sequential voting is inequitable because early voters bear more participation costs. n November 7, 2000, the polls closed in the east- investment of time and resources, such that some voters ern time zone portion of Florida at 7:00 p.m. may choose to abstain. Second, if voters’ behavior does OAt 7:49:40 p.m., while Florida voters in central depend on the voting mechanism, then we might expect time zone counties were still voting, NBC/MSNBC pro- that sequential and simultaneous voting mechanisms jected that the state was in Al Gore’s column.