Woodland Caribou Plan for the Telkwa Subpopulation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer Recreational Access Management Plan for the Bulkley LRMP

Summer Recreational Access Management Plan For the Bulkley LRMP Prepared by Summer RAMP Table Submitted to Bulkley Valley Community Resources Board February 2013 Facilitator Tom Chamberlin Funding provided by Project supported by Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................... 1 List of Tables ..................................................................................................................... 2 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................. 3 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................ 4 1.0 Introduction ................................................................................................................. 5 2.0 History ........................................................................................................................ 5 3.0 Objectives .................................................................................................................... 6 4.0 The Process and the Participants ..................................................................................... 6 4.1 Participants and their Goals ............................................................................................ 6 4.1.1 Bulkley Valley Quad Riders Club ................................................................................... 7 4.1.2 Bulkley -

Submission To: Northern Gateway Joint Review Panel

Submission to: Northern Gateway Joint Review Panel This report was produced by the Office of Wet’suwet’en Natural Resources Department on behalf of all past and present Wet’suwet’en. This report was produced under serious time, money, and capacity constraints. Until such time as Wet’suwet’en title and rights are formally recognized or a treaty successfully concluded with the Crown, the statement of Wet’suwet’en title and rights and their potential infringements must, as the Supreme Court of Canada said in Haida Nation, constitute an interim and preliminary statement of Wet’suwet’en title and rights, not a final one. The Office of the Wet’suwet’en retains all copyright and ownership rights to this submission, which cannot be utilized without written permission. © 2011 The Office of the Wet’suwet’en. 2 | Page Submission to Northern Gateway JRP Submission Summary 1.0 Scope & Approach 1. The Office of the Wet’suwet’en (OW) presents this submission to the Northern Gateway Joint Review Panel. This submission is a component of the Wet’suwet’en response in respect of the proposed Northern Gateway project within Wet’suwet’en territory. 2. The Wet’suwet’en are stewards of the land. They are here to protect their traditional territories and to ensure that future generations of Wet’suwet’en are able to live and benefit from all that their ancestral land provides. The Wet’suwet’en are not opposed to commercial and economic development on their traditional territories as long as the proper cultural protocol is followed and respect given. -

Geological Survey Branch 1988-1989 Project Inventory

Province of British Columbia Ministry of Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BRANCH 1988-1989 PROJECT INVENTORY Victoria 1988 PREFACE This inventory of the major projects the Geological Survey Branch will undertake in Fiscal 1988-89 is primarily designed to inform the exploration industry and interested public of the location and objectives of our 1988 field projects. Project leaders are available for consultation both during and after the field season. This is the most extensive field program undertaken in the history of the Branch. It is made possible by recent significant increases in the base budget; $1.5 million in 1988-89 and $2.0 million in 1987-88, for a total base budget of $6.67 million this year. In addition the Branch has been allocated $1.6 million from the Canada/British Columbia Mineral Development Agreement (MDA) for geoscience programs in 1988. Projects funded by the MDA are identified by an (M) in the text. The major new initiative of the Branch is in 1:50 000 scale regional mapping projects. Maps at this scale have been identified by industry as the fundamental underpinning for exploration work, yet only 5% of British Columbia has been mapped at this or larger scales. Three new mapping projects will be initiated in 1988 in the poorly known, frontier areas in the northwest of the province. These new programs, together with six regional mapping projects and metallogenic industrial mineral and coal already in progress, will be a valuable stimulus and guide to mineral exploration in these areas. Comments, suggestions, and queries regarding the Branch's geoscience program are welcome. -

British Columbia, Canada

THERE’S SO MUCH TO HIKE · THERE’S SO MUCH TO SEE · THERE’S SO MUCH TO SHOP · THERE’S SO MUCH TO EXPLORE · SMITHERSbritish columbia, canada OFFICIAL VISITOR GUIDE www.TourismSmithers.com THERE’S SO MUCH TO HIKE · THERE’S SO MUCH TO SMITHERS · THERE’S SO MUCH TO SHOP · THERE’S SO MUCH TO EXPL SMITHERS’ only FULL SERVICE HOTEL discover the difference ZOER’S MODERN GRILL & LOUNGE · FIRESIDE PUB Relax and enjoy Smithers with the hospitality of the Hudson Bay Lodge. Take in the spectacular view of Hudson Bay Mountain from one of our spacious rooms or relish the comfort of one of our King suites, each with its own electric Å replace. Zoer’s Modern Grill & Lounge is the perfect place for a family meal or a business lunch. Care to try a more casual atmosphere with friends or colleagues? You’ll love the Fireside Pub, where you can watch the sporting events while enjoying one of our many drink specials. MEETING & BANQUET FACILITIES · LODGE LIQUOR STORE AIRPORT SHUTTLE · BUSINESS & FITNESS FACILITIES Toll-free reservation line 1.800.663.5040 www.HudsonBayLodge.com 3251 East Highway 16, Smithers HBL 2419c (Smithers Visitor Guide).indd 1 3/12/2010 12:15:11 PM RE · THERE’S SO MUCH TO GOLF · THERE’S SO MUCH TO FISH · THERE’S SO MUCH TO DISCOVER · THERE’S SO MUCH TO CLIMB CONTENTS there’s so much to smithers! 2 PARADISE FOUND 4 THE POWER OF A PLACE 6 FILL YOUR SOUL, AND YOUR CUP 8 WINTER MAGIC 10 GONE FISHIN’ 12 THRILLS ON TWO WHEELS 13 SMITHERS MAP 14 TELKWA HIGH ROAD CIRCLE TOUR 15 1, 2, 3, FORE! COVER PHOTO 16 TELKWA MAP High above Silver King Basin in the Babine Mountains 18 THE VILLAGE OF TELKWA Provincial Park, a hiker 21 MORICETOWN stops to take in the vista. -

Conserving Skeena Fish Populations and Their Habitat 2002

Conserving Skeena Fish Populations and their Habitat Allen S. Gottesfeld, Ken A. Rabnett, and Peter E. Hall November, 2002 Skeena Fisheries Commission Box 229, Hazelton, BC 250 842-5670 © Skeena Fisheries Commission 2002 The authors’ opinions do not necessarily reflect the policies of the Skeena Fisheries Commission. Comments, corrections, omissions, and information updates are welcome and may be forwarded to the authors. Cover: Coho at Stephens Creek, Kispiox Watershed September 2001. Photo Credit: A. S. Gottesfeld Back Cover: Skeena Watershed Map, Scale 1:2,000,000 Cartography by Gordon Wilson, Gitxsan Watershed A uthorities GIS Dept. Skeena Stage I Watershed-based Fish Sustainability Plan Conserving Skeena Fish Populations and Their Habitat Allen S. Gottesfeld, Ken A. Rabnett, and Peter E. Hall Skeena Fisheries Commission Table of Contents Abstract...................................................................................................................1 The Skeena WFSP Process.....................................................................................2 Context................................................................................................................2 Scope.......................................................................................................................3 Skeena WFSP Planning Process.............................................................................4 Stage I: Establishing Skeena Watershed Priorities.................................................5 Biophysical Profile: -

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Caribou Rangifer

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Caribou Rangifer tarandus Northern Mountain population Central Mountain population Southern Mountain population in Canada Northern Mountain population - SPECIAL CONCERN Central Mountain population - ENDANGERED Southern Mountain population - ENDANGERED 2014 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2014. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Caribou Rangifer tarandus, Northern Mountain population, Central Mountain population and Southern Mountain population in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xxii + 113 pp. (www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/default_e.cfm). Previous report(s): COSEWIC. 2002. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the woodland caribou Rangifer tarandus caribou in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xi + 98 pp. (Species at Risk Status Reports) Thomas, D.C., and D.R. Gray. 2002. Update COSEWIC status report on the woodland caribou Rangifer tarandus caribou in Canada, in COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Woodland Caribou Rangifer tarandus caribou in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-98 pp. Kelsall, J.P. 1984. COSEWIC status report on the woodland caribou Rangifer tarandus caribou in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 103 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Deborah Cichowski for writing the status report on Caribou Rangifer tarandus, Northern Mountain population, Central Mountain population and Southern Mountain population in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada. This status report was overseen and edited by Justina Ray, Co-chair of the COSEWIC Terrestrial Mammals Specialist Subcommittee. -

Landforms of British Columbia 1976

Landforms of British Columbia A Physiographic Outline bY Bulletin 48 Stuart S. Holland 1976 FOREWORD British Columbia has more variety in its climate and scenery than any other Province of Canada. The mildness and wetness of the southern coast is in sharp contrast with the extreme dryness of the desert areas in the interior and the harshness of subarctic conditions in the northernmost parts. Moreover, in every part, climate and vegetation vary with altitude and to a lesser extent with configuration of the land. Although the Province includes almost a thousand-mile length of one of the world’s greatest mountain chains, that which borders the north Pacitic Ocean, it is not all mountainous but contains a variety of lowlands and intermontane areas. Because of the abundance of mountains, and because of its short history of settlement, a good deal of British Columbia is almost uninhabited and almost unknown. However, the concept of accessibility has changed profoundly in the past 20 years, owing largely to the use of aircraft and particularly the helicopter. There is now complete coverage by air photography, and by far the largest part of the Province has been mapped topographically and geologically. In the same period of time the highways have been very greatly improved, and the secondary roads are much more numerous. The averagecitizen is much more aware of his Province, but, although knowledge has greatly improved with access,many misconceptions remain on the part of the general public as to the precise meaning even of such names as Cascade Mountains, Fraser Plateau, and many others. -

<Original Signed By>

Hillslope and Fluvial Processes Along the Proposed Pipeline Corridor, Burns Lake to Kitimat, West Central British Columbia James W. Schwab P.Geo., Eng.L. Prepared by: James W. Schwab P.Geo., Eng.L. Geomorphologist Prepared for: Bulkley Valley Centre for Natural Resources Research & Management Smithers, B.C. Prepared: September, 2011 THIS DOCUMENT HAS RECEIVED AN INDEPENDENT PEER REVIEW Table of Contents Table of Contents .............................................................................. ii List of Figures ................................................................................... iii Executive Summary .......................................................................... iv 1 Introduction ................................................................................... 1 1.1 Regional Setting ....................................................................... 1 1.2 Physiographic Regions ............................................................. 2 1.2.1 Nechako Plateau ........................................................................... 3 1.2.2 Hazelton Mountains ...................................................................... 3 1.2.3 Kitimat Ranges ............................................................................. 3 2 Hillslope and Fluvial Processes ....................................................... 4 2.1 Nechako Plateau ....................................................................... 4 2.1.1 Burns Lake to the Morice River .................................................... -

CATASTROPHIC ROCK AVALANCHES, WEST-CENTRAL BRITISH COLUMBIA James W

CATASTROPHIC ROCK AVALANCHES, WEST-CENTRAL BRITISH COLUMBIA James W. Schwab, BC Forest Service, Smithers, B.C. Marten Geertsema, BC Forest Service, Prince George, B.C. Stephen G. Evans, Geological Survey of Canada, Ottawa, Ont. ABSTRACT The Bulkley and Babine Ranges of the Hazelton-Skeena Mountains, west-central British Columbia, have experienced three recent large catastrophic rock avalanches: Howson, 19 September 1999; Zymoetz, 8 June 2002; Harold Price, 22 or 23 June 2002. These landslides are large relative to contemporary landslides, although many large prehistoric landslides are evident within the Hazelton-Skeena Mountains. The recent landslides may be a result of climate change. Climate warming has resulted in: a pronounced thinning and recession of mountain glaciers causing debutressing of unstable rock slopes; possible degradation of mountain permafrost; and, an apparent increase in precipitation (rain and snow) over the past few years. Large rock avalanches place utilities and transportation routes in the mountain valleys at a significant risk. In addition, risks are increased to forest workers and recreation users in the valleys. The tremendous down valley travel distance of these landslides suggest some communities may also be at risk. RESUME Les chaînes Bulkley et Babine situées dans les montagnes Hazelton-Skeena, au centre-ouest de la Colombie- Britannique ont récemment éprouvé trois grandes avalanches rocheuses catastrophiques, soient à Howson, le 19 002 et à Harold Price, le 22 ou 23 juin, 2002. On considère que ces glissements de terrain sont plus importants que d’autres avalanches rocheuses contemporaines. Par contre, il y a plusieurs glissements de terrain préhistoriques qui sont comparables. Il e terrain soient provoqués par le changement climatique. -

Exploration and Mining in British Columbia, 1998

BRITISH COLUMBIA Minis1:ry of Energy and Mines Energy and Minerals Division Mines Branch EXPLORATION AND MINING IN BRITISH COLUMBIA - 1998 Britbh Cdumbip Cntplo@ng In Publication Dntn Main entry under title: Exploration in British Columbia -1975- Annual. WiuI: Geology in British Columbia, ISSN0823-1257; an4 Mining in MihColumbia, ISSN 0823-1265. mntinuer: Geology. exploration andmining in British Columbia, ISSN 0085-1027. 1979 publid in 1983. Isuingbcdyvaries: 1975-1976,MiofMmesand Petroleum Resource; 1977-1985,Mnimy of Energy, Mines and Permlnrm Rem-; 1986.1996. Geological Survey Branch; 1997- ,Mines Branch ISSN 0823-2059 = Exploration in Briii?h Columbia 1. Rmpaing- British Columbia - Periodicals. 2. Geology, Economic - British Columbia ~ Periodicals 3. Miner and mineral rrsource~~ British Columbia - Periodicals. 1. British Columbia Mi&Mines and Petmleum Resources. 11. British Columbia Minisrry of Eslergy.Mines Md Petroleum Rm- III. British Columbia Geological Survey Branch. 1V. British Columbia Mines Bmch T N270.E96 622.1’09711 TN270.E96 Rev. April 1998 COVER PHOTO.. Exploration campof the Miner River ResourcesEagle Plains Resources joint venture on the GreenlandCreek property in the Purcell Mountains, 30 kilometres northof Kimberley. FOREWORD The total exploration expenditure in British Columbia in 1998 is estimated at between $35 million and $40 million, a dramatic reduction of approximately 50% from the $75 million total in 1997. Four of the five regions experienced sharp reductions ranging from 24% in the Kootenay region to 77% in the South-Central region. Only the Southwestern region reported an expenditure level which was roughly the same as in 1997, although two-thirds of the total was spent on one project, mine-site exploration at Myra Falls. -

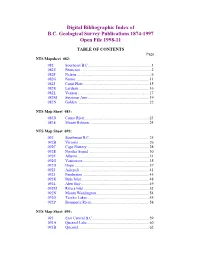

Digital Bibliographic Index of B.C. Geological Survey Publications 1874-1997 Open File 1998-11

Digital Bibliographic Index of B.C. Geological Survey Publications 1874-1997 Open File 1998-11 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page NTS Mapsheet 082: 082 Southeast B.C..............................................................1 082E Penticton.....................................................................2 082F Nelson.........................................................................6 082G Fernie........................................................................11 082J Canal Flats.................................................................15 082K Lardeau.....................................................................16 082L Vernon.......................................................................17 082M Seymour Arm............................................................19 082N Golden.......................................................................22 NTS Map Sheet 083: 083D Canoe River...............................................................23 083E Mount Robson...........................................................24 NTS Map Sheet 092: 092 Southwest B.C...........................................................25 092B Victoria.....................................................................26 092C Cape Flattery.............................................................28 092E Nootka Sound...........................................................30 092F Alberni.......................................................................31 092G Vancouver.................................................................35 -

Hillslope and Fluvial Processes Along the Proposed Pipeline Corridor, Burns Lake to Kitimat, West Central British Columbia

(A40500) Hillslope and Fluvial Processes Along the Proposed Pipeline Corridor, Burns Lake to Kitimat, West Central British Columbia James W. Schwab P.Geo., Eng.L. Prepared by: James W. Schwab P.Geo., Eng.L. Geomorphologist [email protected] Prepared for: Bulkley Valley Centre for Natural Resources Research & Management Smithers, B.C. Prepared: September, 2011 THIS DOCUMENT HAS RECEIVED AN INDEPENDENT PEER REVIEW (A40500) Table of Contents Table of Contents .............................................................................. ii List of Figures ................................................................................... iii Executive Summary .......................................................................... iv 1 Introduction ................................................................................... 1 1.1 Regional Setting ....................................................................... 1 1.2 Physiographic Regions ............................................................. 2 1.2.1 Nechako Plateau ........................................................................... 3 1.2.2 Hazelton Mountains ...................................................................... 3 1.2.3 Kitimat Ranges ............................................................................. 3 2 Hillslope and Fluvial Processes ....................................................... 4 2.1 Nechako Plateau ....................................................................... 4 2.1.1 Burns Lake to the Morice River ....................................................