Title: Digital Games and Biodiversity Conservation Authors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April - June 2021 in This Issue on the Cover Meet Daisy

April - June 2021 IN THIS ISSUE On the Cover Meet Daisy . .2 Update from the Zoo Director . .3 The black and white ruffed lemurs The Traveling Zoo Goes Virtual . .4 are the largest of the Zoo’s three What’s New At The Zoo . .5 lemur species, weighing ten pounds Construction Update . .6 & 7 each! Whether enjoying the after- Meet Robin . .8 noon sun on exhibit or through their BAAZK . 9 den windows, you will be envious DZS Ex. Director Message . 10 of their seemingly laidback lifestyle. Upcoming Events . 11 Come visit the NEW Madagascar ex- hibit, where one female and two male Board of Directors lemurs will be cohabitating with the Photo by: David Haring Arlene Reppa, President ring-tails, crowns, and radiated tortoises Serena Wilson-Archie, Vice President when the weather warms up. Beans (the Gabriel Baldini, Treasurer female), AJ, and Reese are excited for Sarah Cole, Secretary those long, lazy, and sunny summer days! Kevin Brandt Cameron Fee Candice Galvis Linda Gray Meet Daisy Amy Hughes Aaron Klein Megan McGlinchey Michael Milligan William S. Montgomery Cathy Morris Matthew Ritter, (DNREC) Richard Rothwell Daniel F. Scholl Mark Shafer, Executive Director Brint Spencer, Zoo Director Support Staff Melanie Flynn, Visitor Services Manager Jennifer Lynch, Marketing & Hello everyone! I'm Daisy Fiore, the new Assistant Curator of Educa- Special Events Manager tion and I'm thrilled to be joining the Brandywine Zoo! I'm coming most Kate McMonagle recently from Disney's Animal Kingdom where I've had many different Membership & Development Coordinator jobs, including primate keeper, conservation education tour guide, park trainer, animal welfare researcher, and animal nutrition keeper. -

An Enlightened Future for Bristol Zoo Gardens

OURWORLD BRISTOL An Enlightened Future for Bristol Zoo Gardens An Enlightened Future for CHAPTERBristol EADING / SECTIONZoo Gardens OUR WORLD BRISTOL A magical garden of wonders - an oasis of learning, of global significance and international reach forged from Bristol’s long established place in the world as the ‘Hollywood’ of natural history film-making. Making the most of the city’s buoyant capacity for innovation in digital technology, its restless appetite for radical social change and its celebrated international leadership in creativity and story-telling. Regenerating the site of the first provincial zoological garden in the World, following the 185 year old Zoo’s closure, you can travel in time and space to interact in undreamt of ways with the wildest and most secret aspects of the animal kingdom and understand for the first time where humankind really sits within the complex web of Life on Earth. b c OURWORLD BRISTOL We are pleased to present this preliminary prospectus of an alternative future for Bristol's historic Zoo Gardens. We do so in the confidence that we can work with the Zoo, the City of Bristol and the wider community to ensure that the OurWorld project is genuinely inclusive and reflects Bristol’s diverse population and vitality. CONTENTS Foreword 2 A Site Transformed 23 A Transformational Future for the Our Challenge 4 Zoo Gardens 24 Evolution of the Site Through Time 26 Site Today 27 Our Vision 5 Reimagining the Site 32 A Zoo Like No Other 6 Key Design Moves 34 Humanimal 7 Anatomy 38 Time Bridge 10 Alfred the Gorilla Lives Again 12 Supporters And Networks 45 Supporters 46 Networks 56 Advisors and Contact 59 Printed in Bristol by Hobs on FSC paper 1 FOREWORD OURWORLD BRISTOL FOREWORD Photo: © Dave Stevens Our demand for resources has Bristol Zoo will hold fond This century we are already pushed many other memories for so many. -

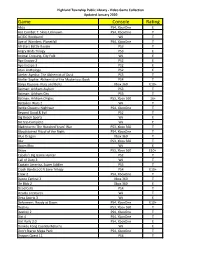

Game Console Rating

Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Abzu PS4, XboxOne E Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown PS4, XboxOne T AC/DC Rockband Wii T Age of Wonders: Planetfall PS4, XboxOne T All-Stars Battle Royale PS3 T Angry Birds Trilogy PS3 E Animal Crossing, City Folk Wii E Ape Escape 2 PS2 E Ape Escape 3 PS2 E Atari Anthology PS2 E Atelier Ayesha: The Alchemist of Dusk PS3 T Atelier Sophie: Alchemist of the Mysterious Book PS4 T Banjo Kazooie- Nuts and Bolts Xbox 360 E10+ Batman: Arkham Asylum PS3 T Batman: Arkham City PS3 T Batman: Arkham Origins PS3, Xbox 360 16+ Battalion Wars 2 Wii T Battle Chasers: Nightwar PS4, XboxOne T Beyond Good & Evil PS2 T Big Beach Sports Wii E Bit Trip Complete Wii E Bladestorm: The Hundred Years' War PS3, Xbox 360 T Bloodstained Ritual of the Night PS4, XboxOne T Blue Dragon Xbox 360 T Blur PS3, Xbox 360 T Boom Blox Wii E Brave PS3, Xbox 360 E10+ Cabela's Big Game Hunter PS2 T Call of Duty 3 Wii T Captain America, Super Soldier PS3 T Crash Bandicoot N Sane Trilogy PS4 E10+ Crew 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dance Central 3 Xbox 360 T De Blob 2 Xbox 360 E Dead Cells PS4 T Deadly Creatures Wii T Deca Sports 3 Wii E Deformers: Ready at Dawn PS4, XboxOne E10+ Destiny PS3, Xbox 360 T Destiny 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt 4 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt Rally 2.0 PS4, XboxOne E Donkey Kong Country Returns Wii E Don't Starve Mega Pack PS4, XboxOne T Dragon Quest 11 PS4 T Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Dragon Quest Builders PS4 E10+ Dragon -

Zoo Tycoon 2001 Manual

HOT KEYS CTRL+B Hide/show buildings CTRL+F Hide/show foliage CTRL+V Hide/show guests CTRL+G Hide/show grid CTRL+S Save a game CTRL+L Load a saved game CTRL+LEFT ARROW Rotate counter-clockwise CTRL+RIGHT ARROW Rotate clockwise CTRL+UP ARROW Zoom in CTRL+DOWN ARROW Zoom out SPACEBAR Pause/resume game PLUS SIGN (+) Increase grid DELETE Clear MINUS SIGN (-) Decrease grid BACKSPACE Undo C Construct exhibit O Display scenario objectives D Adopt animal Z Display Zoo Status H Hire staff G Display Guest Info B Buy buildings/objects E Display Exhibit Info M Show messages A Display Animal Info F Display file options S Display Staff Info Sybex strategy guide included on CD 0603 Part No. X09-78135 SAFETY WARNING GETTING STARTED ..........................................................................................2 PLAYING ZOO TYCOON ...................................................................................3 About Photosensitive Seizures A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain USING THE ZOO TOOLS .................................................................................4 visual images, including flashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Construction ............................................................................................................................................................................5 Contents of Table Even people who have no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause these “photosensitive epileptic -

TPG Index Volumes 1-35 1986-2020

Public Garden Index – Volumes 1-35 (1986 – 2020) #Giving Tuesday. HOW DOES YOUR GARDEN About This Issue (continued) GROW ? Swift 31 (3): 25 Dobbs, Madeline (continued) #givingTuesday fundraising 31 (3): 25 Public garden management: Read all #landscapechat about it! 26 (W): 5–6 Corona Tools 27 (W): 8 Rocket science leadership. Interview green industry 27 (W): 8 with Elachi 23 (1): 24–26 social media 27 (W): 8 Unmask your garden heroes: Taking a ValleyCrest Landscape Companies 27 (W): 8 closer look at earned revenue. #landscapechat: Fostering green industry 25 (2): 5–6 communication, one tweet at a time. Donnelly, Gerard T. Trees: Backbone of Kaufman 27 (W): 8 the garden 6 (1): 6 Dosmann, Michael S. Sustaining plant collections: Are we? 23 (3/4): 7–9 AABGA (American Association of Downie, Alex. Information management Botanical Gardens and Arboreta) See 8 (4): 6 American Public Gardens Association Eberbach, Catherine. Educators without AABGA: The first fifty years. Interview by borders 22 (1): 5–6 Sullivan. Ching, Creech, Lighty, Mathias, Eirhart, Linda. Plant collections in historic McClintock, Mulligan, Oppe, Taylor, landscapes 28 (4): 4–5 Voight, Widmoyer, and Wyman 5 (4): 8–12 Elias, Thomas S. Botany and botanical AABGA annual conference in Essential gardens 6 (3): 6 resources for garden directors. Olin Folsom, James P. Communication 19 (1): 7 17 (1): 12 Rediscovering the Ranch 23 (2): 7–9 AAM See American Association of Museums Water management 5 (3): 6 AAM accreditation is for gardens! SPECIAL Galbraith, David A. Another look at REPORT. Taylor, Hart, Williams, and Lowe invasives 17 (4): 7 15 (3): 3–11 Greenstein, Susan T. -

In-Game, In-Room, In-World: Reconnecting Video Game Play to the Rest of Kids’ Lives." the Ecology of Games: Connecting Youth, Games, and Learning

Citation: Stevens, Reed, Tom Satwicz, and Laurie McCarthy. “In-Game, In-Room, In-World: Reconnecting Video Game Play to the Rest of Kids’ Lives." The Ecology of Games: Connecting Youth, Games, and Learning. Edited by Katie Salen. The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Series on Digital Media and Learning. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2008. 41–66. doi: 10.1162/dmal.9780262693646.041 Copyright: c 2008 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Published under Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative ⃝ Works Unported 3.0 license. In-Game, In-Room, In-World: Reconnecting Video Game Play to the Rest of Kids’ Lives Reed Stevens University of Washington, LIFE Center, College of Education Tom Satwicz University of Georgia, Learning and Performance Support Laboratory Laurie McCarthy University of Washington, LIFE Center, College of Education Introduction One of the burning questions that people ask about video games, including most parents we’ve told about our study of young people playing video games in their homes, is whether playing these games affects kids’ lives when the machine is off. In particular, people want to understand what young people learn playing games that they use, or adapt, in the rest of their lives. This question is the focus of our chapter. Learning scientists use the term transfer to refer to the phenomenon of taking what you have learned in one context and transferring it to another. Without getting into the technical details, we note that academic discussions about transfer are fraught with theoretical confu- sions and fierce debate. Not only do learning scientists disagree about what causes transfer or what prevents it from happening, they disagree even about what counts as transfer (i.e., knowing when they see it) and how to assess it when they think it might be taking place. -

Between Species: Choreographing Human And

BETWEEN SPECIES: CHOREOGRAPHING HUMAN AND NONHUMAN BODIES JONATHAN OSBORN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN DANCE STUDIES YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO MAY, 2019 ã Jonathan Osborn, 2019 Abstract BETWEEN SPECIES: CHOREOGRAPHING HUMAN AND NONHUMAN BODIES is a dissertation project informed by practice-led and practice-based modes of engagement, which approaches the space of the zoo as a multispecies, choreographic, affective assemblage. Drawing from critical scholarship in dance literature, zoo studies, human-animal studies, posthuman philosophy, and experiential/somatic field studies, this work utilizes choreographic engagement, with the topography and inhabitants of the Toronto Zoo and the Berlin Zoologischer Garten, to investigate the potential for kinaesthetic exchanges between human and nonhuman subjects. In tracing these exchanges, BETWEEN SPECIES documents the creation of the zoomorphic choreographic works ARK and ARCHE and creatively mediates on: more-than-human choreography; the curatorial paradigms, embodied practices, and forms of zoological gardens; the staging of human and nonhuman bodies and bodies of knowledge; the resonances and dissonances between ethological research and dance ethnography; and, the anthropocentric constitution of the field of dance studies. ii Dedication Dedicated to the glowing memory of my nana, Patricia Maltby, who, through her relentless love and fervent belief in my potential, elegantly willed me into another phase of life, while she passed, with dignity and calm, into another realm of existence. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my phenomenal supervisor Dr. Barbara Sellers-Young and my amazing committee members Dr. -

FUTURE of ZOOS SYMPOSIUM, 10-11 February 2012 Canisius College, Buffalo, New York

Design and Architecture: Third Generation Conservation, Post- Immersion and Beyond FUTURE OF ZOOS SYMPOSIUM, 10-11 February 2012 Canisius College, Buffalo, New York Jon Coe, Jon Coe Design <[email protected]> Introduction Will zoos in the next fifty or one hundred years be as different from those today as today’s zoos are from those a century and half century ago? Yes and no. Yes, some zoos will evolve so far as to no longer be considered zoos at all. Early examples of these transcended “unzoos” exist around us today, largely unregarded by the zoo profession. Much heralded personal virtual zoos and Jurassic Park-like theme parks for NeoGen chimeras will also be popular. No, some zoos in less developed regions of the globe will remain much as zoos were in the early 1900’s with simple rows of pens and cages. William Conway, David Hancocks and I, along with several other speakers today, remember zoo facilities of fifty years ago very well indeed, having both experienced them and played our parts in helping to transform them. Some older zoos have relics of their hundred year old past. So looking forward 50 and 100 years isn’t too daunting. In fact science fiction writers have been describing believable future wildlife encounters for us. Examples include Ray Bradbury’s “The Veldt” in the Illustrated Man1 and David Brin’s Uplift Series2 which will figure into my predictions later. While aquariums will also undergo dramatic change, especially in response to energy conservation, I have reluctantly left them out of this paper in order to focus on land- based developments. -

Alphabetical Order (Created & Managed by Manyfist)

Jump List • Alphabetical Order (Created & Managed by Manyfist) 1. 007 2. 80’s Action Movie 3. A Certain Magical Index 4. A Song of Fire & Ice 5. Ace Attorney 6. Ace Combat 7. Adventure Time 8. Age of Empires III 9. Age of Ice 10. Age of Mythology 11. Aion 12. Akagi 13. Alan Wake 14. Alice: Through the Looking Glass 15. Alice's Adventures in Wonderland 16. Alien 17. Alpha Centauri 18. Alpha Protocol 19. Animal Crossing 20. Animorphs 21. Anno 2070 22. Aquaria 23. Ar Tonelico 24. Archer 25. Aria 26. Armored Core 27. Assassin’s Creed 28. Assassination Classroom 29. Asura’s Crying 30. Asura’s Wrath 31. Austin Powers 32. Avatar the Last Airbender 33. Avatar the Legend of Korra 34. Avernum! 35. Babylon 5 36. Banjo Kazooie 37. Banner Saga 38. Barkley’s Shut & Jam Gaiden 39. Bastion 40. Battlestar Galactica 41. Battletech 42. Bayonetta 43. Berserk 44. BeyBlade 45. Big O 46. Binbougami 47. BIOMEGA 48. Bionicle 49. Bioshock 50. Bioshock Infinite 51. Black Bullet 52. Black Lagoon 53. BlazBlue 54. Bleach 55. Bloodborne 56. Bloody Roar 57. Bomberman 64 58. Bomberman 64 Second Attack 59. Borderlands 60. Bravely Default 61. Bubblegum Crisis 2032 62. Buffy The Vampire Slayer 63. Buso Renkin 64. Cardcaptor Sakura 65. Cardfight! Vanguard 66. Career Model 67. Carnival Phantasm 68. Carnivores 69. Castlevania 70. CATstrophe 71. Cave Story 72. Changeling the Lost 73. Chroma Squad 74. Chronicles of Narnia 75. City of Heroes 76. Civilization 77. Claymore 78. Code Geass 79. Codex Alera 80. Command & Conquer 81. Commoragth 82. -

THE GARDEN of INTELLIGENCE Re; Forming the Denatured

THE GARDEN OF INTELLIGENCE Re; forming the denatured. Richard Weller Man doth like the ape, in that the higher he climbs the more he shows his arse.i Francis Bacon INTRODUCTION This article emanates from a studio based on designing an Orang-utan enclosure in the Perth Zoo. *** The Garden of Intelligence was a zoological garden created by the Chinese emperor Wen Wang circa 1000 BC.ii It is recorded that scholars would sit in this garden and discuss questions such as whether or not fish had desires.iii Now we can move through the Tokyo Zoo in armored cars, shop (and live) in Edmonton Mall with flamingos when it is -10C outside, send monkeys into orbit, attach human ears to rats and baboon's hearts to humans. These achievements are made possible because as Richard Leakey says, “We feel ourselves special. We have an unmatched capacity for spoken language and we can shape our world as no other can” .iv The design of zoos as simulated environments predicated on environmental anxieties is particularly close to the heart of landscape architecture's, and increasingly architecture's environmental concerns. The crisis of representation in zoos and the tangle of aesthetic guises which simplify the complexity of zoos meanings, makes them pertinent prisms through which to reflect upon our role within the community of living beings. As Levi Strauss said, "animals are good to think with".v Less abstracted from organic origins than architecture and more directly concerned with living things other than humans, landscape architecture has an historic role in the formation of symbolic microcosms in which the rubric of nature is both subject and object. -

Microsoft Game Studios Scales up Tape Storage

CUSTOMER SUCCESS STORY Microsoft Game Studios Scales “Our storage growth has been very dynamic, Three years ago we were at 17TB, now we have 40TB and Up Tape Storage we are projecting 50-60 TB within the year. With our ever increasing WINNING THE STORAGE GAME workload, I needed a scalable, Microsoft Game Studios (MGS) may be in the entertainment business, but when it comes to taking care reliable backup solution that was of storage, it doesn't play around. also easy to manage.” “Our storage growth has been very dynamic,” said Jason Reiner, IT Operations Manager for MGS in Jason Reiner, Microsoft Redmond, Wash. “Three years ago we were at 17TB, now we have 40TB and we are projecting 50-60 TB IT Operations Manager for MGS in within the year. With our ever increasing workload, I needed a scalable, reliable backup solution that was Redmond, Wash. also easy to manage” MGS is a wholly owned Microsoft subsidiary containing a number of independent game development studios, some which were acquired by Microsoft. MGS provides centralized support out of its SOLUTION OVERVIEW headquarters in Redmond, Washington, but some of the acquired studios continue to operate in other cities or countries, developing their signature games. Quantum Scalar i500 tape library Turn 10 studio, which created the popular Forza Motorsport series on Xbox, is one of the on-site studios based at Microsoft headquarters. All told, MGS has between 10 and 20 active studios and 2,000 users in LTO-3 tape drives (x8) the U.S. China, U.K. and Japan. -

REID PARK ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY 2019-2020 Annual Report Dear Zoo Friends, Fiscal Year 2019-2020 Started out As One of the Zoo’S Best Ever

REID PARK ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY 2019-2020 Annual Report Dear Zoo Friends, Fiscal year 2019-2020 started out as one of the Zoo’s best ever. We were experiencing record attendance and celebrating the return of the Asian Lantern Festival when the pandemic hit and the Zoo closed for five months during our peak season as we did our part to stem the spread of the COVID virus. Zoo staff took a deep breath, rolled up their sleeves from wherever they were, and pitched in across departments however they were needed. • Animal care staff took the opportunity to provide additional enrichment for animals who weren’t used to seeing quiet, empty sidewalks. • The grounds and maintenance team did some deep cleaning and took care of some projects like replacing water lines which are easiest done when there are no visitors in the Zoo. Construction began on the new Flamingo Lagoon and new Welcome Plaza. • The marketing and education teams immediately got busy on social and digital media, finding ways to engage guests with a visit to the Zoo without being here in person. During the process, we found that not only were our regular guests logging in, but guests from across the country and around the world were also following the Zoo. • Our volunteers switched their daily meetings from in-person to online, staying current with the Zoo while earning their Continuing Education hours so they would be ready to jump back in when the time was right. • Our development team kept our donors connected to the Zoo and up-to-date on capital projects.