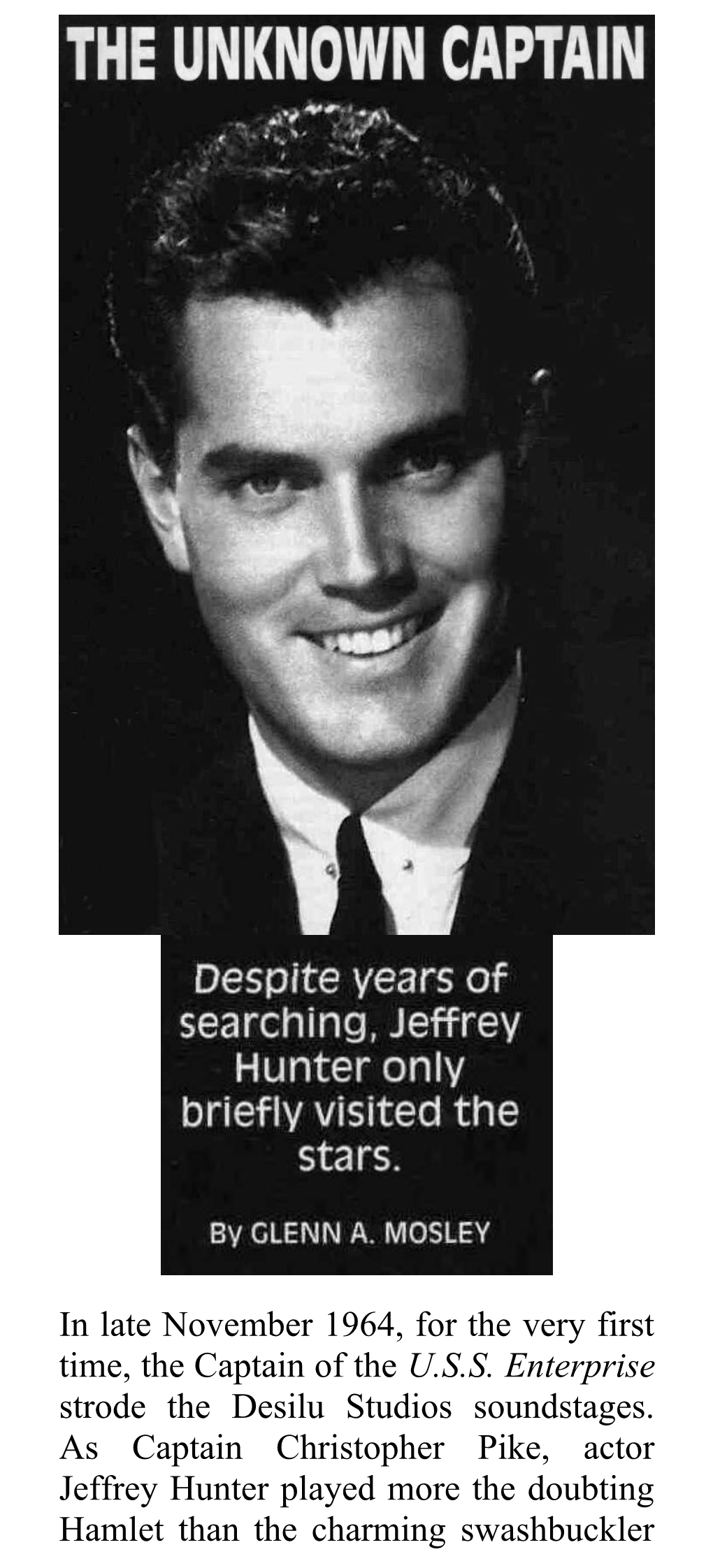

The Unknown Captain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brokeback and Outback

[CINEMA] ROKEBACK AND OUTBACK BRIAN MCFARLANE WELCOMES THE LATEST COMEBACK OF THE WESTERN IN TWO DISPARATE GUISES FROM time to time someone pronounces 'The Western is dead.' Most often, the only appropriate reply is 'Long live the Western!' for in the cinema's history of more than a century no genre has shown greater longevity or resilience. If it was not present at the birth of the movies, it was there shortly after the midwife left and, every time it has seemed headed for the doldrums, for instance in the late 1930s or the 1960s, someone—such as John Ford with Stagecoach (1939) or Sergio Leone and, later, Clint Eastwood—comes along and rescues it for art as well as box office. Western film historian and scholar Edward Buscombe, writing in The BFI Companion to the Western in 1988, not a prolific period for the Western, wrote: 'So far the genre has always managed to renew itself ... The Western may surprise us yet.' And so it is currently doing on our screens in two major inflections of the genre: the Australian/UK co-production, John Hillcoat's The Proposition, set in [65] BRIAN MCFARLANE outback Australia in the 1880s; and the US film, Ang Lee's Brokeback Mountain, set largely in Wyoming in 1963, lurching forwards to the 1980s. It was ever a char acteristic of the Western, and a truism of writing about it, that it reflected more about its time of production than of the period in which it was set, that it was a matter of America dreaming about its agrarian past. -

Innovators: Filmmakers

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES INNOVATORS: FILMMAKERS David W. Galenson Working Paper 15930 http://www.nber.org/papers/w15930 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 April 2010 The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2010 by David W. Galenson. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Innovators: Filmmakers David W. Galenson NBER Working Paper No. 15930 April 2010 JEL No. Z11 ABSTRACT John Ford and Alfred Hitchcock were experimental filmmakers: both believed images were more important to movies than words, and considered movies a form of entertainment. Their styles developed gradually over long careers, and both made the films that are generally considered their greatest during their late 50s and 60s. In contrast, Orson Welles and Jean-Luc Godard were conceptual filmmakers: both believed words were more important to their films than images, and both wanted to use film to educate their audiences. Their greatest innovations came in their first films, as Welles made the revolutionary Citizen Kane when he was 26, and Godard made the equally revolutionary Breathless when he was 30. Film thus provides yet another example of an art in which the most important practitioners have had radically different goals and methods, and have followed sharply contrasting life cycles of creativity. -

Red and White on the Silver Screen: the Shifting Meaning and Use of American Indians in Hollywood Films from the 1930S to the 1970S

RED AND WHITE ON THE SILVER SCREEN: THE SHIFTING MEANING AND USE OF AMERICAN INDIANS IN HOLLYWOOD FILMS FROM THE 1930s TO THE 1970s a dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Bryan W. Kvet May, 2016 (c) Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials Dissertation Written by Bryan W. Kvet B.A., Grove City College, 1994 M.A., Kent State University, 1998 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2015 Approved by ___Kenneth Bindas_______________, Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Dr. Kenneth Bindas ___Clarence Wunderlin ___________, Members, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Dr. Clarence Wunderlin ___James Seelye_________________, Dr. James Seelye ___Bob Batchelor________________, Dr. Bob Batchelor ___Paul Haridakis________________, Dr. Paul Haridakis Accepted by ___Kenneth Bindas_______________, Chair, Department of History Dr. Kenneth Bindas ___James L. Blank________________, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Dr. James L. Blank TABLE OF CONTENTS…………………………………………………………………iv LIST OF FIGURES………………………………………………………………………v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………...vii CHAPTERS Introduction………………………………………………………………………1 Part I: 1930 - 1945 1. "You Haven't Seen Any Indians Yet:" Hollywood's Bloodthirsty Savages……………………………………….26 2. "Don't You Realize this Is a New Empire?" Hollywood's Noble Savages……………………………………………...72 Epilogue for Part I………………………………………………………………..121 Part II: 1945 - 1960 3. "Small Warrior Should Have Father:" The Cold War Family in American Indian Films………………………...136 4. "In a Hundred Years it Might've Worked:" American Indian Films and Civil Rights………………………………....185 Epilogue for Part II……………………………………………………………….244 Part III, 1960 - 1970 5. "If Things Keep Trying to Live, the White Man Will Rub Them Out:" The American Indian Film and the Counterculture………………………260 6. -

John Ford Birth Name: Sean Aloysius O'feeney Director, Producer

John Ford Birth name: Sean Aloysius O'Feeney Director, Producer Birth Feb 1, 1895 (Cape Elizabeth, ME) Death Aug 31, 1973 (Palm Desert, CA) Genres Drama, Western, Romance, Comedy Maine-born John Ford originally went to Hollywood in the shadow of his older brother, Francis, an actor/writer/director who had worked on Broadway. Originally a laborer, propman's assistant, and occasional stuntman for his brother, he rose to became an assistant director and supporting actor before turning to directing in 1917. Ford became best known for his Westerns, of which he made dozens through the 1920s, but he didn't achieve status as a major director until the mid-'30s, when his films for RKO (The Lost Patrol [1934], The Informer [1935]), 20th Century Fox (Young Mr. Lincoln [1939], The Grapes of Wrath [1940]), and Walter Wanger (Stagecoach [1939]), won over the public, the critics, and earned various Oscars and Academy nominations. His 1940s films included one military-produced documentary co-directed by Ford and cinematographer Gregg Toland, December 7th (1943), which creaks badly today (especially compared with Frank Capra's Why We Fight series); a major war film (They Were Expendable [1945]); the historically-based drama My Darling Clementine (1946); and the "cavalry trilogy" of Fort Apache (1948), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), and Rio Grande (1950), each of which starred John Wayne. My Darling Clementine and the cavalry trilogy contain some of the most powerful images of the American West ever shot, and are considered definitive examples of the Western. Ford also had a weakness for Irish and Gaelic subject matter, in which a great degree of sentimentality was evident, most notably How Green Was My Valley (1941) and The Quiet Man (1952), which was his most personal film, and one of his most popular. -

John Ford Birth Name: John Martin Feeney (Sean Aloysius O'fearna)

John Ford Birth Name: John Martin Feeney (Sean Aloysius O'Fearna) Director, Producer Birth Feb 1, 1895 (Cape Elizabeth, ME) Death Aug 31, 1973 (Palm Desert, CA) Genres Drama, Western, Romance, Comedy Maine-born John Ford originally went to Hollywood in the shadow of his older brother, Francis, an actor/writer/director who had worked on Broadway. Originally a laborer, propman's assistant, and occasional stuntman for his brother, he rose to became an assistant director and supporting actor before turning to directing in 1917. Ford became best known for his Westerns, of which he made dozens through the 1920s, but he didn't achieve status as a major director until the mid-'30s, when his films for RKO (The Lost Patrol [1934], The Informer [1935]), 20th Century Fox (Young Mr. Lincoln [1939], The Grapes of Wrath [1940]), and Walter Wanger (Stagecoach [1939]), won over the public, the critics, and earned various Oscars and Academy nominations. His 1940s films included one military-produced documentary co-directed by Ford and cinematographer Gregg Toland, December 7th (1943), which creaks badly today (especially compared with Frank Capra's Why We Fight series); a major war film (They Were Expendable [1945]); the historically-based drama My Darling Clementine (1946); and the "cavalry trilogy" of Fort Apache (1948), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), and Rio Grande (1950), each of which starred John Wayne. My Darling Clementine and the cavalry trilogy contain some of the most powerful images of the American West ever shot, and are considered definitive examples of the Western. Ford also had a weakness for Irish and Gaelic subject matter, in which a great degree of sentimentality was evident, most notably How Green Was My Valley (1941) and The Quiet Man (1952), which was his most personal film, and one of his most popular. -

Rope-Assisted Search Procedures in Large-Area Structures by MIKE MASON

Continuing Education Course Rope-Assisted Search Procedures in Large-Area Structures BY MIKE MASON Program supported through an educational grant provided by: TRAINING THE FIRE SERVICE FOR 134 YEARS To earn continuing education credits, you must successfully complete the course examination. The cost for this CE exam is $25.00. For group rates, call (973) 251-5055. Rope-Assisted Search Procedures in Large-Area Structures Educational Objectives On completion of this course, students will 1. Identify and understand the need for search in large- 4. Identify and perform the techniques and maneuvers area structures while being able to recognize hazards of proficient rope line management, including locating when searching for distressed firefighters or civilians. distressed firefighters or civilians, incorporating their health assessment, and removing them along the main 2. Assemble and construct the proper search rope bag sys- search rope line when exiting a large-area structure. tem as well as position members and identify their roles and responsibilities in a rope-assisted search. 5. Recognize and discuss the importance of air manage- ment, accountability, command and control, and com- 3. Identify and demonstrate the principles of anchor, point, munications regarding firefighter Maydays and civilian and shoot as they pertain to object and human anchors rescues. while also identifying techniques in rope tethering. B Y M I K E M A S O N in equipment and techniques sometimes turn out to be less than ideal. the focus here is to assist you and your Any fiRe departmentS thRoughout department in establishing simple, accountable, safe the country could never imagine facing the procedures for rope-assisted searches in large and many M task of rescuing a trapped, lost, or uncon- times confusing areas. -

Open GRAFF Thesis Final Draft.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School School of Music INDIAN IDENTITY: CASE STUDIES OF THREE JOHN FORD NARRATIVE WESTERN FILMS A Thesis in Musicology by Peter A. Graff © 2013 Peter A. Graff Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts May 2013 ii The thesis of Peter A. Graff was reviewed and approved* by the following: Charles Youmans Associate Professor of Musicology Thesis Advisor Marica S. Tacconi Professor of Musicology Sue Haug Professor of Music Director of the School of Music *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Music in John Ford’s Westerns reveals increasingly complex and sympathetic depictions of Native Americans throughout his filmography. While other directors of the genre tend to showcase a one-dimensional “brutal savage” archetype (especially in the early sound era), Ford resisted this tendency in favor of multidimensional depictions. As a director, Ford was particularly opinionated about music and wielded ultimate control over the types of songs used in his films. The resulting artworks, visual and aural, were therefore the vision of one creator. To investigate the participation of music in Ford’s approach, I have investigated three archetypal products of the Western’s three early periods: The Iron Horse (1924), Stagecoach (1939), and The Searchers (1956). In The Iron Horse, an Indian duality is visually present with the incorporation of friendly Pawnees and destructive Cheyennes. My recent recovery of the score, however, reveals a more complicated reading due to thematic borrowing that identifies white characters as the source of Indian aggression. Stagecoach builds upon this duality by adding a third morally ambiguous Indian character, Yakima. -

Place Images of the American West in Western Films

PLACE IMAGES OF THE AMERICAN WEST IN WESTERN FILMS by TRAVIS W. SMITH B.S., Kansas State University, 2003 M.A., Kansas State University, 2005 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Geography College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2016 Abstract Hollywood Westerns have informed popular images of the American West for well over a century. This study of cultural, cinematic, regional, and historical geography examines place imagery in the Western. Echoing Blake’s (1995) examination of the novels of Zane Grey, the research questions analyze one hundred major Westerns to identify (1) the spatial settings (where the plot of the Western transpires), (2) the temporal settings (what date[s] in history the Western takes place), and (3) the filming locations. The results of these three questions illuminate significant place images of the West and the geography of the Western. I selected a filmography of one hundred major Westerns based upon twenty different Western film credentials. My content analysis involved multiple viewings of each Western and cross-referencing film content like narrative titles, American Indian homelands, fort names, and tombstone dates with scholarly and popular publications. The Western spatially favors Apachería, the Borderlands and Mexico, and the High Plains rather than the Pacific Northwest. Also, California serves more as a destination than a spatial setting. Temporally, the heart of the Western beats during the 1870s and 1880s, but it also lives well into the twentieth century. The five major filming location clusters are the Los Angeles / Hollywood area and its studio backlots, Old Tucson Studios and southeastern Arizona, the Alabama Hills in California, Monument Valley in Utah and Arizona, and the Santa Fe region in New Mexico. -

What Is a Western? Politics and Self- Knowledge in John Ford's The

What Is a Western? Politics and Self- Knowledge in John Ford’s The Searchers Robert B. Pippin It is generally agreed that while, from the silent film The Great Train Rob- bery (1903) until the present, well over seven thousand Westerns have been made it was not until three seminal articles in the nineteen fifties by Andre´ Bazin and Robert Warshow that the genre began to be taken seriously. Indeed Bazin argued that the “secret” of the extraordinary persistence of the Western must be due to the fact that the Western embodies “the essence of cinema,” and he suggested that that essence was its incorporation of myth and a mythic consciousness of the world.1 He appeared to mean by this that Westerns This article is the third of the Castle lectures delivered at Yale University in early 2008. The series was given again at the University of Chicago in the spring of that year. It is also a chapter of a forthcoming book based on these lectures, Political Psychology, American Myth, and Some Hollywood Westerns. I am very grateful to Yale and to Seyla Benhabib for the invitation to give the Castle lectures (and for their willingness to permit me such an unusual approach to issues in political philosophy); to Bob von Hallberg for encouraging me to give the series at Chicago and for supporting such a series; and to Greg Freeman and Jonny Thakkar for their help in the organization and publicity for those lectures. All of the work on the Westerns book was made possible by the Andrew W. -

The Berkhofer Duality Revealed in the Western Films of John Ford and John Wayne

The Berkhofer Duality Revealed in the Western Films of John Ford and John Wayne John T. Nelson University of Toledo 1 Robert F. Berkhofer, Jr. argues that the United States has categorized Native Americans in polarized stereotypes of noble savage or vicious heathen. He contends that scholarly interest in Indian culture has risen and subsided in tandem with its emphasis in popular culture. Since motion pictures represent a significant component of popular culture, this paper proposes to examine the representation of Native Americans in Western film. The research focuses on the major works of John Ford and John Wayne, dominant contributors to the genre in direction and acting, respectively. The investigation assesses the portrayal of aboriginal peoples as a means of studying American perceptions of their culture. These secondary sources inform the study. Berkhofer notes the legacy and depth of the Western genre for Americans.1 In Six Guns and Society, Will Wright examines its popularity stating: For the Western, like any myth, stands between individual human consciousness and society. If a myth is popular, it must somehow appeal to or reinforce the individuals who view it by communicating a symbolic meaning to them. This meaning must, in turn, reflect the particular social institutions and attitudes that have created and continue to nourish the myth. Thus, a myth must tell its viewers about themselves and their society.2 Cultural historian Russel Nye describes the popular arts as works of humanistic form reflecting the tastes and values of the public in the preface to his study.3 The monograph by Ralph Brauer researches the television format of Western imagery.4 John G. -

The Searchers (1956) Is Considered by Many to Be a True American Masterpiece of Filmmaking, and the Best and Perhaps Most-Admired Film of Director John Ford

The Searchers (1956) is considered by many to be a true American masterpiece of filmmaking, and the best and perhaps most-admired film of director John Ford. It was his 115th feature film, and he was already a four-time Best Director Oscar winner (The Informer (1935), The Grapes of Wrath (1940), How Green Was My Valley (1941), and The Quiet Man (1952)) - all for his pictures of social comment rather than his quintessential westerns. With dazzling on-location, VistaVision photography (including the stunning red sandstone rock formations of Monument Valley) by Winton C. Hoch in Ford's most beloved locale, the film handsomely captures the beauty and isolating danger of the frontier. However, at its time, the sophisticated, modern, visually- gorgeous film was unappreciated, misunderstood, and unrecognized by critics and did not receive a single Academy Award nomination. The film's screenplay was adapted by Frank S. Nugent (director Ford's son-in-law) from Alan Le May's 1954 novel of the same name, that was first serialized as a short story in late fall 1954 issues of the Saturday Evening Post, and first titled The Avenging Texans. Various similarities existed between the film's script and an actual Comanche kidnapping of a young white girl in Texas in 1936. The Searchers tells the emotionally complex story of a perilous, hate-ridden quest and Homeric-style odyssey of self-discovery after a Comanche massacre, while also exploring the themes of racial prejudice and sexism. Its meandering tale examines the inner psychological turmoil of a fiercely independent, crusading man obsessed with revenge and hatred, who searches for his two nieces (Pippa Scott and Natalie Wood) among the "savages" over a five-year period. -

Ford Was a Storyteller Who Loved to Create and Manipulate Myths, And

Ford was a storyteller who loved to create and manipulate myths, and as he grew older and more complex, he loved to challenge them as well, reaffirming the audience's deepest conventional wisdom and then gently shattering it. Despite all of his personal setbacks, he rose to the height of his creative powers in The Searchers. He is responsible for the film's visual poetry- its skill in moving from the intimacy of domestic interiors and family life to the terrible beauty of the gothic sandstone cathedrals and vast, obliterating plains of Monument Valley- as well as it deep and passionate emotions. At the heart of The Searchers is John Wayne's towering performance as Ethan Edwards. Despite his reputation for knowing how to play only the righteous hero, Wayne had portrayed morally ambiguous men before, most notably the autocratic trail boss in Red River (1948) and the brutish Marine sergeant in Sands of Iwo Jima (1949). But in The Searchers, he is darker, angrier and more troubled than ever. This dark knight is determined to exterminate the damsel and anyone who stands in his way. He shoots the eyes out of a Comanche Indian corpse, scalps another dead Indian, disrupts a funeral service, fires at warriors collecting their dead and wounded from the battlefield, and slaughters a buffalo herd to deprive Comanche families of food for the winter. Still, because he is played by John Wayner, we identify with Ethan's quest even as we recoil from his purpose. His charisma draws us in, making us complicit in his terrible vendetta.